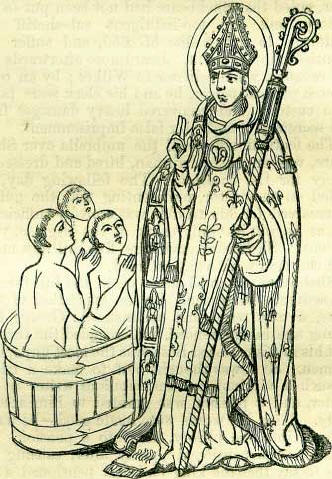

6th DecemberBorn: Henry VI of England, 1421, Windsor; Baldassarre Castiglione, diplomatist and man of letters, 1478, Casatico, near Mantua; General George Monk, Duke of Albemarle, 1608, Potheridge, Devonshire; Sir David Baird, hero of Seringapatam, 1757, Newbyth, Scotland; Rev. Richard Harris Barham, author of the Ingoldsby Legends, 1788, Canterbury. Died: Otho II, Emperor of Germany, 983, Reese; Alphonse I of Portugal, 1185, Coimbra; Pope Clement VI, 1352, Avignon; Dr. John Lightfoot, divine and commentator, 1675, Great Munden, Herts; Nicholas Rowe, dramatist, 1718, London; Florent Carton Dancourt, comic dramatist, 1726; Catharine Clive, celebrated comic actress, 1785, Strawberry Hill, Twickenham. Feast Day: St. Theophilus, bishop of Antioch, confessor, 190. St. Nicholas, confessor, archbishop of Myra, 342. Saints Dionysia, Dativa, Aemilianus, Boniface, Leontia, Tertius, and Majoricus, martyrs, 484. St. Peter Paschal, bishop and martyr, 1300. ST. NICHOLASSt. Nicholas belongs to the fourth century of the Christian era, and was a native of the city of Patara, in Lycia, in Asia Minor. So strong were his devotional tendencies, even from infancy, that we are gravely informed that he refused to suck on Wednesdays and Fridays, the fast-days appointed by the church! Having embraced a religious life by entering the monastery of Sion, near Myra, he was in course of time raised to the dignity of abbot, and for many years made himself conspicuous by acts of piety and benevolence. Subsequently he was elected archbishop of the metropolitan church of Myra, and exercised that office with great renown till his death. Though escaping actual martyrdom, he is said to have suffered imprisonment, and otherwise testified to the faith under the persecution of Dioclesian. As with St. Cuthbert, the history of St. Nicholas does not end with his death and burial. His relics were preserved with great honour at Myra, till the end of the eleventh century, when certain merchants of Bari, on the Adriatic, moved by a pious indignation similar to what actuated the Crusaders, made an expedition to the coast of Lycia, and landing there, broke open the coffin containing the bones of the saint, and carried them off to Italy. They landed at Bari on the 9th of May 1087, and the sacred treasure, which they had brought with them, was deposited in the church of St. Stephen. On the day when the latter proceeding took place, we are told that thirty persons were cured of various distempers through imploring the intercession of St. Nicholas, and since that time his tomb at Bari has been famous for pilgrimages. In the ensuing article a description is given of the annual celebration of his. festival in that seaport. Perhaps no saint has enjoyed a more extended popularity than St. Nicholas. By the Russian nation, he has been adopted as their patron, and in England no fewer than three hundred and seventy-two churches are named in his honour. He is regarded as the special guardian of virgins, of children, and of sailors. Scholars were under his protection, and from the circumstance of these being anciently denominated clerks, the fraternity of parish clerks placed themselves likewise under the guardianship of St. Nicholas. He even came to be regarded as the patron of robbers, from an alleged adventure with thieves, whom he compelled to restore some stolen goods to their proper owners. But there are two specially celebrated legends regarding this saint, one of which bears reference to his protectorship of virgins, and the other to that of children. The former of these stories is as follows: A nobleman in the town of Patara had three daughters, but was sunk in such poverty, that he was not only unable to provide them with suitable marriage-portions, but was on the point of abandoning them to a sinful course of life from inability to preserve them otherwise from starvation. St. Nicholas, who had inherited a large fortune, and employed it in innumerable acts of charity, no sooner heard of this unfortunate family, than he resolved to save it from the degradation with which it was threatened. As he proceeded secretly to the nobleman's house at night, debating with himself how he might best accomplish his object, the moon shone out from behind a cloud, and shewed him an open window into which he threw a purse of gold. This fell at the feet of the father of the maidens, and enabled him to portion his eldest daughter. A second nocturnal visit was paid to the house by the saint, and a similar present bestowed, which procured a dowry for the second daughter of the nobleman. But the latter was now determined to discover his mysterious benefactor, and with that view set himself to watch. On St. Nicholas approaching, and preparing to throw in a purse of money for the third daughter, the nobleman caught hold of the skirt of his robe, and threw himself at his feet, exclaiming: '0 Nicholas! servant of God! why seek to hide thyself?' But the saint made him promise that he would inform no one of this seasonable act of munificence. From this incident in his life is derived apparently the practice formerly, if not still, customary in various parts of the continent, of the elder members and friends of a family placing, on the eve of St. Nicholas's Day, little presents, such as sweetmeats and similar gifts, in the shoes or hose of their younger relatives, who, on discovering them in the morning, are supposed to attribute them to the munificence of St. Nicholas. In convents, the young lady-boarders used, on the same occasion, to place silk-stockings at the door of the apartment of the abbess, with a paper recommending themselves to 'Great St. Nicholas of her chamber.' The next morning they were summoned together, to witness the results of the liberality of the saint who had bountifully filled the stockings with sweetmeats. From the same instance of munificence recorded of St. Nicholas, he is often represented bearing three purses, or three gold balls; the latter emblem forming the well-known pawnbrokers' sign, which, with considerable probability, has been traced to this origin. It is true, indeed, that this emblem is proximately derived from the Lombard merchants who settled in England at an early period, and were the first to open establishments for the lending of money. The three golden balls were also the sign of the Medici family of Florence, who, by a successful career of merchandise and money-lending, raised themselves to the supreme power in their native state. But the same origin is traceable in both cases-the emblematic device of the charitable St. Nicholas. The second legend to which we have adverted is even of a more piquant nature. A gentleman of Asia sent his two sons to be educated at Athens, but desired them, in passing through the town of Myra, to call on its archbishop, the holy Nicholas, and receive his benediction.  The young men, arriving at the town late in the evening, resolved to defer their visit till the morning, and in the meantime took up their abode at an inn. The landlord, in order to obtain possession of their baggage, murdered the unfortunate youths in their sleep; and after cutting their bodies to pieces, and salting them, placed the mutilated remains in a pickling tub along with some pork, under the guise of which he resolved to dispose of the contents of the vessel. But the archbishop was warned by a vision of this horrid transaction, and proceeded immediately to the inn, where he charged the landlord with the crime. The man, finding himself discovered, confessed his guilt, with great contrition, to St. Nicholas, who not only implored on his behalf the forgiveness of Heaven, but also proceeded to the tub where the remains of the innocent youths lay in brine, and then made the sign of the cross, and offered up a supplication for their restoration to life. Scarcely was the saint's prayer finished, when the detached and mangled limbs were miraculously reunited, and the two youths regaining animation, rose up alive in the tub, and threw themselves at the feet of their benefactor. We are further informed, that the archbishop refused their homage, desiring the young men to return thanks to the proper quarter from which this blessing had descended; and then, after giving them his benediction, he dismissed them with great joy to continue their journey to Athens. In accordance with this legend, St. Nicholas is frequently represented, as delineated in the accompanying engraving, standing in full episcopal costume beside a tub with naked children. An important function assigned to St. Nicholas, is that of the guardianship of mariners, who in Roman Catholic countries regard him with special reverence. In several seaport towns there are churches dedicated to St. Nicholas, whither sailors resort to return thanks for preservation at sea, by hanging up votive pictures, and making other offerings. This practice is evidently a relic of an old pagan custom alluded to by Horace: Me tabulâ, sacer Votivâ paries indicat uvida Suspendisse potenti Vestimenta marls Deo. The office of protector of sailors, thus attributed in ancient times to Neptune, was afterwards transferred to St. Nicholas, who is said, on the occasion of making a voyage to the Holy Land, to have caused by his prayers a tempest to assuage, and at another time to have personally appeared to, and saved some mariners who had invoked his assistance. THE FEAST OF ST. NICHOLASThe Feast of St. Nicholas, at Bari, is one of the chief ecclesiastical festivals of Southern Italy. It is attended by pilgrims in thousands, who come from considerable distances. From the Tronto to Otranto, the whole eastern slope of the Apennines sends eager suppliants to this famous shrine, and nowhere is there more distinctly to be seen how firm and deep a hold the faith in which they have been educated has on the enthusiastic nature of the Italian peasantry, than at this sanctuary, and on this occasion. Bari is a city of considerable importance, being the second in population of those belonging to the Neapolitan provinces. It is situated on the Adriatic coast, half-way between the spur, formed by Monte Gargano, and the heel of the boot. It contains some 40,000 inhabitants, and is capital of the province of the same name, which contains half a million of population. The city occupies a small peninsula, which escapes, as it were, into the blue waters of the Adriatic, from the bosom of the richest and most fertile country in Italy. The whole sea-board, from the mouths of the Ofanto to within a few miles of the magnificent but neglected harbour of Brindisi, recalls the descriptions given of Palestine in its ancient and highly-cultivated state. The constant industry of the people-in irrigation, in turning over the soil, in pruning the exuberant vegetation-is rewarded by a harvest in every month of the year, and the wealth of the soil is expressed by the contented aspect, the decent clothing, and the personal adornment with rings, chains, and ear-rings, of both men and women. Stockings and even gloves are commonly worn, and that not as being needed for defence against the climate, but as marks of decent competence. At Barletta, the great grain-port, which is situated between this garden of Italy and the great pastoral plain of Apulia, there is a labour-market held daily, during the summer months, at four A.M. There the labourers meet, before going to their daily toil, to settle the price of labour, and to arrange for the due distribution of workmen through the country. Each man is attended by his dog, and most of them mount their asses, at the conclusion of this ancient and admirable congress, to ride to the scene of their occupation. The harvests of this fertile country commence, in the latter part of April and earlier portion of May, by the gathering of the pulse crops, those of beans especially, on which the people subsist for some weeks, and of vetches. Oranges and lemons succeed during the month of May, and the country affords many species of these fruit, one at least of which, as large as a child's head, and with a thick and edible rind, is unknown in other parts of Europe. In June, succeeds the harvest of oats, barley, and wheat, and the gathering of flax. In July, the maize is harvested; a plant which has been regarded as of American origin, but which is represented in the frescoes of Pompei as boiled and eaten precisely as we see it used at the present day. July is also the chief month for the making of cheese, as well as for the silk crop, or the tending of the silk-worm till it forms its cocoons. August produces cotton, tobacco, and figs. September yields grapes and a second shearing of wool, the first having taken place in May. The next five months, in fertile years, supply a constant yield of olives; and the plucking and preserving of the fruit, as well as the manufacture of oil, afford continual occupation. The olive, which, in the south of France, appears as a small shrub, covers the hills to the south of the Ofanto, with trees about the size of the apple-trees of the Gloucestershire and Herefordshire orchards; and yet further south, in the Terra di Otranto, it rises into the magnitude of a forest-tree, and covers large districts of country with a rich and shady woodland. The culture and the varieties of the olive are the same with those that are so minutely described by Virgil, and the flavour of the edible species, and the delicacy and filbert-like aroma of the new-made oil, can only be appreciated by a visit to a country like Apulia. In March, the latest addition to the production of the country, the little Mandarin orange, becomes ripe; a delicious fruit, too delicate to export. Introduced into Italy during the present generation, it has already much increased in size, at the expense, it is said, of flavour. In April is the season for the slaughtering of fatted animals, which brings us round again to the wool-crop. Bari is an archiepiscopal city, but its ancient cathedral, with its almost picturesque architecture, is outshone by the splendour of the Church of St. Nicholas, the 'protector of the city.' The grand prior of St. Nicholas is one of the chief ecclesiastical dignitaries in Italy, claiming to rank with the bishop of Loretto, the archbishop of Milan, and the cardinal of Capua. The king of Naples for the time is, when he enters the precincts of St. Nicholas, a less person than the grand prior, ranking always, however, as the first canon of the chapter, and having a throne in the choir erected for his occupation in that capacity. The present grand prior is a man every way fitted to sustain such a dignity -courteous and affable, erect and vigorous in form and gait, and clear and bright in complexion, although hard on fourscore years of age. He is the very counterpart of the pictures of Fenelon, but of Fenelon unworn by the charge of the education of a dauphin. It so chanced that the writer was in Bari, and was the guest of this respectable prelate, on the two great festivals that are distinctive of the city that of St. Mark, and that of St. Nicholas. On St. Mark's Day, the chief peculiarity is the procession of the clergy and municipality to the walls of the ancient castle that overlook the sea, and the solemn firing of a cannon thrice in the direction of Venice, in acknowledgment of the relief afforded by the Venetian fleet when Bari was besieged by the Saracens in 1002 A.D. The ricochet of the cannon-ball over the surface of the Adriatic is watched with the greatest interest by the people, and the distance from the shore at which the water is struck appears to be regarded as ominous. But on the festa of St. Nicholas, in addition to the rejoicings of the citizens, and to the influx of the contadini, the city is absolutely invaded by an army of pilgrims. With staves bound with olive, with pine, or with palm, each bearing a suspended water-bottle formed out of a gourd, frequently barefoot, clothed in every variety of picturesque and ancient costume, devotees from every province of the kingdom of Naples seek health or other blessings at the shrine of the great St. Nicholas. The priory gives to each a meal, and affords shelter to many. Others fill every arch or sheltered nook in the walls, bivouac in the city, or spend the night in devotion. The grand vicar of the priory said that on that morning they had given food to nine thousand pilgrims, and there are many who never seek the dole, but travelling on horseback or in carriages to within a few miles of Bari, assume the pilgrim habit only to enter the very precincts of the shrine. The clergy composing the chapter of St. Nicholas are not slow to maintain the thaumaturgic character of their patron, and seem to believe in it. The bones of the saint are deposited in a sepulchre beneath the magnificent crypt, which is in itself a sort of subterranean church, of rich Saracenic architecture. Through the native rock which forms the tomb, water constantly exudes, which is collected by the canons on a sponge attached to a reed, squeezed into bottles, and sold to the pilgrims, as a miraculous specific, under the name of the `Manna of St. Nicholas.' As a proof of its supernatural character, a large bottle was shewn to me, in which, suspended from the cork, grew and floated the delicate green bladder of one of the Adriatic ulvae. I suppose that its growth in fresh water had been extremely slow, for a person, whose word I did not doubt, assured me that he remembered the bottle from his childhood, and that the vegetation was then much less visible. 'This,' said the grand vicar, a tall aquiline-featured priest, who looked as if he watched the effect of every word upon a probable heretic- this we consider to be conclusive as to the character of the water. If vegetation takes place in water that you keep in a jar, the water becomes offensive. This bottle has been in its present state for many years. You see the vegetation. But it is not putrid. Taste it, you will find it perfectly sweet. Questa è prodigiosa. I trust that all the water that was sold to the pilgrims was really thus afforded by St. Nicholas, if its efficacy be such as is asserted to be the case; but on this subject the purchasers must rely implicitly on the good faith of the canons, as mere human senses cannot distinguish it from that of the castle well. The pilgrims, on entering the Church of St. Nicholas, often shew their devotion by making the circuit once, or oftener, on their knees. Some are not content with this mark of humility, but actually move around the aisles with the forehead pressed to the marble pavement, being generally led by a child, by means of a string or handkerchief, of which they hold the corner in the mouth. It is impossible to conceive anything more calculated to stir the heart with mingled feelings of pity, of admiration, of sympathy, and of horror than to see these thousands of human beings recalling, in their physiognomy, their dialects, their gesticulations, even their dresses, the Magna Graecia of more than two thousand years ago, urged from their distant homes by a strong and intense piety, and thinking to render acceptable service by thus debasing themselves below the level of the brute. The flushed face, starting eyes, and scarred forehead, fully distinguish such of the pilgrims as have thus sought the benediction of the saint. The mariners of Bari take their own part, and that a very important one, in the functions of the day, and go to a considerable expense to perform their duty with eclat. Early in the morning, they enter the church in procession, and receive from the canons the wooden image of the saint, attired in the robes and mitre of an archbishop, which they bear in triumph through the city, attended by the canons only so far as the outer archway of the precincts of the priory. They take their charge to visit the cathedral and other places, and then fairly embark him, and carry him out to sea, where they keep him until nightfall. They then return, disembark under the blaze of illumination, bon-fires, and fireworks, and the intonation, by the whole heaving mass of the population, of a Gregorian Litany of St. Nicholas; parade the town, visit by torchlight, and again leave, his own church; and finally, and late in the night, return the image to the reverend custody of the canons, who, in their purple robes and fur capes turned up with satin, play only a subordinate part in the solemnity. 'It is the only time,' said a thickly-moustached bystander- it is the only occasion, in Italy, on which you see the religion of Jesus Christ in the hands of the people. The conduct of the festa was, indeed, in the bands of the mariners and of the pilgrims; the character of the religion is a different question. Those who have witnessed the festa of St. Januarius, at Naples, will err if they endeavour thence to realise the character of the festa of St. Nicholas at Bari. The effect on the mind is widely different. Without the frantic excitement that marks the Neapolitan festival, there is a deep, serious, anxious conviction that pervades the thousands who assemble at Bari, which renders the commemoration of St. Nicholas an event unique in its nature. The nocturnal procession, the flashing torches, the rockets, the deep-toned litany, the hum and surge of the people through the ancient archways, the thousands of pilgrims that seem to have awakened from a slumber of seven centuries, all tend power-fully to affect the imagination. But the chief element of this power over the mind is to be found in the deep earnestness of so great a mass of human beings, while the stars look down calm and solemn on their time-honoured rite, and a deep bass to their litany rolls in from the waves of the Adriatic. THE BOY-BISHOPOn St. Nicholas's Day, in ancient times, a singular ceremony used to take place. This was the election of the Boy-bishop, or Episcopus Puerorum, who, from this date to Innocents', or Childermas Day, on 28th December, exercised a burlesque episcopal jurisdiction, and, with his juvenile dean and prebendaries, parodied the various ecclesiastical functions and ceremonies. It is well known that, previous to the Reformation, these profane and ridiculous mummeries were encouraged and participated in by the clergy themselves, who, confident of their hold on the reverence or superstition of the populace, seem to have entertained no apprehension of the dangerous results which might ultimately ensue from such sports, both as regarded their own influence and the cause of religion itself. The election of the Boy-bishop seems to have prevailed generally throughout the English cathedrals, and also in many of the grammar-schools, but the place where, of all others, it appears to have specially obtained, was the episcopal diocese of Salisbury or Sarum. A full description of the mock-ceremonies enacted on the occasion is pre-served in the Processional of Salisbury Cathedral, where also the service of the Boy-bishop is printed and set to music. It seems to have constituted literally a mimic transcript of the regular episcopal functions; and we do not discover any trace of parody or burlesque, beyond the inevitable one of the ludicrous contrast presented by the diminutive bishop and his chapter to the grave and canonical figures of the ordinary clergy of the cathedral. The actors in this solemn farce were composed of the choristers of the church, and must have been well drilled in the parts which they were to per-form. The boy who filled the character of bishop, derived some substantial benefits from his tenure of office, and is said to have had the power of disposing of such prebends as fell vacant during the period of his episcopacy. If he died in the course of it, he received the funeral honours of a bishop, and had a monument erected to his memory, of which latter distinction an example may be seen on the north side of the nave of Salisbury Cathedral, where is sculptured the figure of a youth clad in episcopal robes, with his foot on a lion-headed and dragon-tailed monster, in allusion to the expression of the Psalmist: Conculcabis leonem et draconem- [Thou shalt tread on the lion and the dragon]. Besides the regular buffooneries throughout England of the Boy-bishop and his companions in church, these pseudo-clergy seem to have perambulated the neighbourhood, and enlivened it with their jocularities, in return for which a contribution, under the designation of the 'Bishop's subsidy,' would be demanded from passers-by and householders. Occasionally, royalty itself deigned to be amused with the burlesque ritual of the mimic prelate, and in 1299, we find Edward I, on his way to Scotland, permitting a Boy-bishop to say vespers before him in his chapel at Heton, near Newcastle-on-Tyne, on the 7th of December, the day after St. Nicholas's Day. On this occasion, we are informed that his majesty made a handsome present to this mock-representative of Episcopacy, and the companions who assisted him in the discharge of his functions. During the reign of Queen Mary of persecuting memory, we find a performance by one of these child-bishops before her majesty, at her manor of St-James-in-the-Fields, on St. Nicholas's Day and Innocents' Day, 1555. This queen restored, on her accession, the ceremonial, referred to, which had been abrogated by her father, Henry VIII, in 1542. We accordingly read in Strype's Ecclesiastical Memorials, quoted by Brand, that on 13th November 1554, an edict was issued by the bishop of London to all the clergy of his diocese to have the procession of a boy-bishop. But again we find that on 5th December, or St. Nicholas's Eve, of the same year, ' at even-song time, came a commandment that St. Nicholas should not go abroad or about. But notwithstanding, it seems so much were the citizens taken with the mock of St. Nicholas-that is, a boy-bishop-that there went about these St. Nicholases in divers parishes, as in St. Andrew's, Holborn, and St. Nicholas Olaves, in Bread Street. The reason the procession of St. Nicholas was forbid, was because the cardinal had, this St. Nicholas Day, sent for all the convocation, bishops, and inferior clergy, to come to him to Lambeth, there to be absolved from all their per-juries, schisms, and heresies.' Again Strype informs us that, in 1556, on the eve of his day, St. Nicholas, that is, a boy habited like a bishop in pontifcalibus, went abroad in most parts of London, singing after the old fashion, and was received with many ignorant but well-disposed people into their houses, and had as much good cheer as ever was wont to be had before, at least, in many places. With the final establishment of Protestantism in England, the pastime of the Boy-bishop disappeared; but the well-known festivity of the Eton Montem appears to have originated in, and been a continuance under another form, of the medieval custom above detailed. The Eton celebration, now abolished, consisted, as is well known, in a march of the scholars attending that seminary to Salt Hill, in the neighbourhood [AD MONTEM-' To the Mount '-whence the name of the festivity], where they dined, and afterwards returned in procession to Eton in the evening. It was thoroughly of a military character, the mitre and ecclesiastical vestments of the Boy-bishop and his clergy of former times being exchanged for the uniforms of a company of soldiers and their captain. Certain boys, denominated salt-bearers, and their scouts or deputies, attired in fancy-dresses, thronged the roads in the neighbourhood, and levied from the passersby a tribute of money for the benefit of their captain. This was supposed to afford the latter the means of maintaining himself at the university, and amounted sometimes to a considerable sum, occasionally reaching as high as £1000. According to the ancient practice, the salt-bearers were accustomed to carry with them a handkerchief filled with salt, of which they bestowed a small quantity on every individual who contributed his quota to the subsidy. The origin of this custom of distributing salt is obscure, but it would appear to have reference to those ceremonies so frequently practised at schools and colleges in former times, when a new-comer or freshman arrived, and, by being salted, was, by a variety of ceremonies more amusing to his companions than himself, admitted to a participation with the other scholars in their pastimes and privileges. A favourite joke at Eton in former times was, it is said, for the salt-bearers to fill with the commodity which they carried, the mouth of any stolid-looking countryman, who, after giving them a trifle, asked for an equivalent in return. About the middle of the last century, the Eton Montem was a biennial, but latterly it became a triennial ceremony. One of the customs, certainly a relic of the Boy-bishop revels, was, after the pro-cession reached Salt Hill, for a boy habited like a parson to read prayers, whilst another officiated as clerk, who at the conclusion of the service was kicked by the parson downhill. This part of the ceremonies, however, was latterly abrogated in deference, as is said, to the wishes of Queen Charlotte, who, on first witnessing the practice, had expressed great dissatisfaction at its irreverence. The Eton-Montem festival found a stanch patron in George III, who generally attended it with his family, and made, along with them, liberal donations to the salt-bearers, besides paying various attentions to the boys who filled the principal parts in the show. Under his patronage the festival flourished with great splendour; but it afterwards fell off, and at last, on the representation of the master of Eton College to her Majesty and the government, that its continuance had become undesirable, the Eton Montem was abolished in January 1847. This step, however, was not taken without a considerable amount of opposition. In recent times, the Eton-Montem festival used to be celebrated on Whit-Tuesday, but previous to 1759, it took place on the first Tuesday in Hilary Term, which commences on 23rd January. It then not unfrequently became necessary to cut a passage through the snow to Salt Hill, to allow the pro-cession to pass. At a still remoter period, the celebration appears to have been held before the Christmas holidays, on one of the days between the feasts of St. Nicholas and the Holy Innocents, the period during which the Boy-bishop of old, the precursor of the 'captain' of the Eton scholars, exercised his prelatical functions. THE INTRODUCTION OF TEADr. Johnson gives Earls Arlington and Ossory the credit of being the first to import tea into England. He says that they brought it from Holland in 1666, and that their ladies taught women of quality how to use it. Pepys, however, records having sent for a cup of tea, a China drink of which he had never drunk before, on the 25th of September 1660; and by an act of parliament of the same year, a duty of eightpence a gallon was levied on all sherbert, chocolate, and tea made for sale. Waller, writing on some tea commended by Catherine of Braganza, says: The best of herbs and best of queens we owe To that bold naticn, which the way did shew To the fair region where the sun does rise. The Muses' friend, Tea, does our fancy aid, Repress the vapours which the head invade, And keeps the palace of the soul serene. Her majesty may have helped to render tea-drinking fashionable, but the beverage was well known in London before the Restoration. The Mercurius Politicus of September 30, 1658, contains the following advertisement: 'That excellent, and by all physicians approved, China drink, called by the Chineans Tcha, by other nations Tay, alias Tee, is sold at the Sultaness Head Coffee-House, in Sweeting's Rents, by the Royal Exchange, London.' Possibly this announcement prompted the founder of Garraway's to issue the broadsheet, preserved in the British Museum Library, in which he thus runs riot in exaltation of tea: 'The quality is moderately hot, proper for winter or summer. The, drink is declared to be most wholesome, preserving in perfect health until extreme old age. The particular virtues are these. It maketh the body active and lusty. It helpeth the headache, giddiness and heaviness thereof. It removeth the obstructions of the spleen. It is very good against the stone and gravel It taketh away the difficulty of breathing, opening obstructions. It is good against lippitude distillations, and cleareth the sight. It removeth lassitude, and cleanseth and purifieth adust humours and a hot liver. It is good against crudities, strengthening the weakness of the stomach, causing good appetite and digestion, and particularly for men of a corpulent body, and such as are great eaters of flesh. It vanquisheth heavy dreams, easeth the brain, and strengtheneth the memory. It overcome-tit superfluous sleep, and prevents sleepiness in general, a draught of the infusion being taken; so that, without trouble, whole nights may be spent in study without hurt to the body. It prevents and cures agues, surfeits, and fevers by infusing a fit quantity of the leaf; thereby provoking a most gentle vomit and breathing of the pores, and hath been given with wonderful success. It (being prepared and drunk with milk and water) strengtheneth the inward parts and prevents consumptions. It is good for colds, dropsies, and scutvies, and expelleth infection.. . And that the virtue and excellence of the leaf and drink are many and great, is evident and manifest by the high esteem and use of it (especially of late years), by the physicians and knowing men in France, Italy, Holland, and other parts of Christendom, and in England it hath been sold in the leaf for six pounds, and sometimes for ten pounds the pound-weight; and in respect of its former scarceness and dearness, it hath been only used as a regalia in high treatments and entertainments, and presents made thereof to princes and grandees till the year 1657.' Having furnished these excellent reasons why people should buy tea, Mr. Garway proceeds to tell them why they should buy it of him: 'The said Thomas Garway did purchase a quantity thereof, and first publicly sold the said tea in leaf and drink, made according to the directions of the most knowing merchants and travellers into those Eastern countries; and upon knowledge and experience of the said Garway's continued care and industry in obtaining the best tea, and making drink thereof, very many noblemen, physicians, merchants, and gentlemen of quality, have ever since sent to him for the said leaf, and daily resort to his house in Exchange Alley, to drink the drink thereof. And to the end that all persons of eminency and quality, gentlemen and others, who have occasion for tea in leaf, may be supplied, these are to give notice that the said Thomas Garway hath tea to sell from sixteen shillings to fifty shillings the pound.' Rugge's Diurnal tells us that tea was sold in almost every street in London, in 1659, and it stood so high in estimation, that, two years later, the East India Company thought a couple of pounds a gift worthy the acceptance of the king. Its use spread rapidly among the wealthier classes, although the dramatists railed against it as only fit for women, and men who lived like women. In 1678, we find Mr. Henry Saville writing to his uncle, Secretary Coventry, in disparagement of some of his friends who have fallen into `the base unworthy Indian practice' of calling for tea after dinner in place of the pipe and bottle, seeming to hold with Poor Robin that 'Arabian tea Is dishwater to a dish of whey.' The enemies of the new fashion attacked it as an innocent pretext for bringing together the wicked of both sexes, and ladies were accused of slipping out of a morning: 'To Mrs. Thoddy's To cheapen tea, without a bodice.' Dean Swift thus sketches a tea-table scene: Let me now survey Our madam o'er her evening tea, Surrounded with the noisy clans Of prudes, coquettes, and harridans. Now voices over voices rise, While each to be the loudest vies. They contradict, affirm, dispute; No single tongue one moment mute; All mad to speak and none to hearken, They set the very lapdog barking, Their chattering makes a louder din, Than fishwives o'er a cup of gin; Far less the rabble roar and rail, When drunk with sour election ale! Scandal, if the poets are to be believed, was always an indispensable accompaniment of the cheering cup: 'Still, as their ebbing Malice it supplies, Some victim falls, some reputation dies.' And Young exclaims: Tea! how I tremble at thy fatal stream! As Lethe dreadful to the love of fame. What devastations on thy banks are seen, What shades of mighty names that once have been! A hecatomb of characters supplies Thy painted altars' daily sacrifice! Other writers denounced tea on economicalgrounds. The Female Spectator (1745) declares the tea-table 'costs more to support than would maintain two children at nurse; it is the utter destruction of all economy, the bane of good-housewifery, and the source of idleness.' That it was still a luxury rather than a necessity, is plain from the description of the household management of a model country rector, as given in The World (1753). 'His only article of luxury is tea, but the doctor says he would forbid that, if his wife could forget her London education. However, they seldom offer it but to the best company, and less than a pound will last them a twelvemonth.' What would the frugal man have thought of the country lady mentioned by Southey, who, on receiving a pound of tea as a present from a town-friend, boiled the whole of it in a kettle, and served up the leaves with salt and butter, to her expectant neighbours, who had been invited specially to give their opinions on the novelty! They unanimously voted it detestable, and were astonished that even fashion could make such a dish palatable. Count Belchigen, physician to Maria Theresa, ascribed the increase of new diseases to the weakness and debility induced by daily drinking tea; but as a set-off, allowed it to be a sovereign remedy for excessive fatigue, pleurisy, vapours, jaundice, weak lungs, leprosy, scurvy, consumption, and yellow fever. Jonas Hanway was a violent foe to tea. In an essay on its use, he ascribes the majority of feminine disorders to an indulgence in the herb, and more than hints that the same vice has lessened the vigour of Englishmen, and deprived Englishwomen of beauty. He is horrified at the fact of no less than six ships and some five hundred seamen being employed in the trade between England and China! Johnson reviewed the essay in the Literary Magazine, prefacing his criticism with the candid avowal that the author: is to expect little justice from a hardened and shameless tea-drinker, who has for twenty years diluted his meals with only the infusion of this fascinating plant; whose kettle has scarcely time to cool; who with tea amuses the evening, with tea solaces the midnight, and with tea welcomes the morning. Spite of this threatening exordium, the doctor's defence of his beloved drink is but weak and lukewarm. He admits that tea is not fitted for the lower classes, as it only gratifies the taste without nourishing the body, and styles it 'a barren superfluity,' proper only to amuse the idle, relax the studious, and dilute the meals of those who cannot use exercise, and will not practise abstinence. For such an inveterate tea-drinker, the following is but faint praise: Tea, among the greater part of those who use it most, is drunk in no great quantity. As it neither exhilarates the heart, nor stimulates the palate, it is commonly an entertainment merely nominal, a pretence for assembling to prattle, for interrupting business or diversifying idleness. He gives the annual importation then (1757) as about four million pounds, 'a quantity,' he allows, 'sufficient to alarm us.' What would the doctor say now, when, as evening closes in, almost every English household gathers round the table, where The cups That cheer but not inebriate wait on each, and the quantity of the article imported is nearly twentyfold what he regards in so serious a light? |