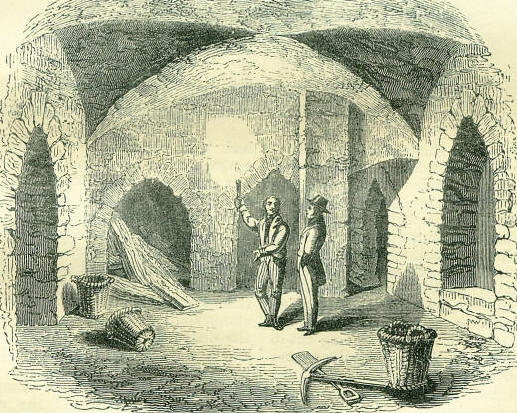

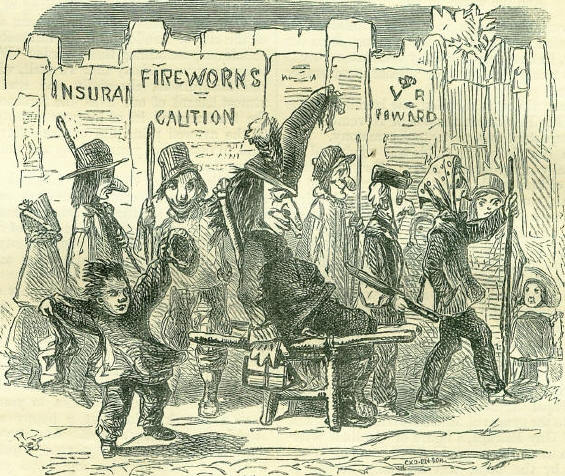

5th NovemberBorn: Hans Sachs, German poet, 1494, Nuremberg; Dr. John Brown, miscellaneous writer, 1715, Rothbury, Northumberland. Died: Maria Angelica Kaufmann, portrait-painter, 1807, Rome. Feast Day: St. Bertille, abbess of Chelles, 692 THE GUNPOWDER PLOTThe 5th of November marks the anniversary of two prominent events in English history-the discovery and prevention of the gunpowder treason, and the inauguration of the Revolution of 1688 by the landing of William III in Torbay. In recent years, an additional interest has been attached to the date, from the victory at Inkerman over the Russians, in the Crimea, being gained on this day in 1854. Like the Bartholomew massacre at Paris in 1572, and the Irish massacre of 1641, the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, standing as it were midway, at a distance of about thirty years from each of these events, has been the means of casting much obloquy on the adherents of the Roman Catholic religion. It would, however, be a signal injustice to connect the Catholics as a body with the perpetration of this atrocious attempt, which seems to have been solely the work of some fanatical members of the extreme section of the Jesuit party. The accession of James I to the throne had raised considerably the hopes of the English Catholics, who, relying upon some expressions which he had made use of while king of Scotland, were led to flatter themselves with the prospect of an unrestricted toleration of the practice of their faith, when he should succeed to the crown of England. Nor were their expectations altogether disappointed. The first year of James's reign shews a remarkable diminution in the amount of fines paid by popish recusants into the royal exchequer, and for a time they seem to have been comparatively unmolested. But such halcyon-days were not to be of long continuance. The English parliament was determined to discountenance in every way the Roman Catholic religion, and James, whose pecuniary necessities obliged him to court the good-will of the Commons, was forced to comply with their importunities in putting afresh into execution the penal laws against papists. Many cruel and oppressive severities were exercised, and it was not long till that persecution which is said to make 'a wise man mad,' prompted a few fanatics to a scheme for taking summary vengeance on the legislature by whom these repressive measures were authorised. The originator of the Gunpowder Plot was Robert Catesby, a gentleman of ancient family, who at one period of his life had become a Protestant, but having been reconverted to the Catholic religion, had endeavoured to atone for his apostasy by the fervour of a new zeal. Having revolved in his own mind a project for destroying, at one blow, the King, Lords, and Commons, he communicated it to Thomas Winter, a Catholic gentleman of Worcestershire, who at first expressed great horror, but was afterwards induced to cooperate in the design. He it was who procured the co-adjutorship of the celebrated Guido or Guy Fawkes, who was not, as has sometimes been represented, a low mercenary ruffian, but a gentleman of good family, actuated by a spirit of ferocious fanaticism. Other confederates were gradually assumed, and in a secluded house in Lambeth, oaths of secrecy were taken, and the communion administered to the conspirators by Father Gerard, a Jesuit, who, however, it is said, was kept in ignorance of the plot. One of the party, named Thomas Percy, a distant relation of the Earl of Northumberland, and one of the gentleman-pensioners at the court of King James, agreed to hire a house adjoining the building where the parliament met, and it was resolved to effect the purpose of blowing the legislature into the air by carrying a mine through the wall. This was in the spring of 1604, but various circumstances prevented the commencement of operations till the month of December of that year.  The gunpowder conspirators-from a print published immediately after the discovery In attempting to pierce the wall of the Parliament House, the conspirators found that they had engaged in a task beyond their strength, owing to the immense thickness of the barrier. With an energy, however, befitting a better cause, they continued their toilsome labours; labours the more toilsome to them, that the whole of the confederates were, without exception, gentlemen by birth and education, and totally unused to severe manual exertion. To avert suspicion while they occupied the house hired by Percy, they had laid in a store of provisions, so that all necessity for going out to buy these was obviated. Whilst in silence and anxiety they plied their task, they were startled one day by hearing, or fancying they heard, the tolling of a bell deep in the ground below the Parliament House. This cause of perturbation, originating perhaps in a guilty conscience, was removed by an appliance of superstition. Holy-water was sprinkled on the spot, and the tolling ceased. Then a rumbling noise was heard directly over their heads, and the fear seized them that they had been discovered. They were speedily, however, reassured by Fawkes, who, on going out to learn the cause of the uproar, ascertained that it had been occasioned by a dealer in coal, who rented a cellar below the House of Lords, and who was engaged in removing his stock from that place of deposit to another. Here was a golden opportunity for the conspirators. The cellar was forth-with hired from the coal merchant, and the working of the mine abandoned. Thirty-six barrels of gunpowder, which had previously been deposited in a house on the opposite side of the river, were then secretly conveyed into this vault. Large stones and bars of iron were thrown in, to increase the destructive effects of the explosion, and the whole was carefully covered up with fagots of wood.  These preparations were completed about the month of May 1605, and the confederates then separated till the final blow could be struck. The time fixed for this was at first the 3rd of October, the day on which the legislature should meet; but the opening of parliament having been prorogued by the king to the 5th of November, the latter date was finally resolved on. Extensive preparations had been made during the summer months, both towards carrying the design into execution, and arranging the course to be followed after the destruction of the king and legislative bodies had been accomplished. New confederates were assumed as participators in the plot, and one of these, Sir Everard Digby, agreed to assemble his Catholic friends on Dunsmore Heath, in Warwickshire, as if for a hunting-party, on the 5th of November. On receiving intelligence of the execution of the scheme, they would be in full readiness to complete the revolution thus inaugurated, and settle a new sovereign on the throne. The proposed successor to James was Prince Charles, afterwards Charles I, seeing that his elder brother Henry, Prince of Wales, would, it was expected, accompany his father to the House of Lords, and perish along with him. In the event of its being found impossible to gain possession of the person of Prince Charles, then it was arranged that his sister, the Princess Elizabeth, should be seized, and carried off to a place of security. Guy Fawkes was to ignite the gunpowder by means of a slow-burning match, which would allow him time to escape before the explosion, and he was then to embark on board a ship waiting in the river for him, and proceed to Flanders. The fatal day was now close at hand, but by this time several dissensions had arisen among the conspirators on the question of giving warning to some special friends to absent themselves from the next meeting of parliament. Catesby, the prime mover in the plot, protested against any such communications being made, asserting that few Catholic members would be present, and that, at all events: rather than the project should not take effect, if they were as dear unto me as mine own son, they also must be blown up. A similar stoicism was not, however, shared by the majority of the con-federates, and one of them at least made a communication, by which the plot was discovered to the government, and its execution prevented. Great mystery attaches to the celebrated anonymous letter received on the evening of 26th October by Lord Mounteagle, a Roman Catholic nobleman, and brother-in-law of Francis Tresham, one of the conspirators. Its authorship is ascribed, with great probability, to the latter, but strong presumptions exist that it was not the only channel by which the king's ministers received intelligence of the schemes under preparation. It has even been surmised that the letter was merely a blind, concerted by a previous understanding with Lord Mounteagle, to conceal the real mode in which the conspiracy was unveiled. Be this as it may, the communication in question was the only avowed or ascertained method by which the king's ministers were guided in detecting the plot. It seems also now to be agreed, that the common story related of King James's sagacity in deciphering the meaning of the writer of the letter, was merely a courtly fable, invented to flatter the monarch and procure for him with the public the credit of a subtle and far-seeing perspicacity. The enigma, if enigma it really was, had been read by the ministers Cecil and Suffolk, and communicated by them to various lords of the council, several days before the subject was mentioned to the king, who at the time of the letter to Lord Mounteagle being received was absent on a hunting expedition at Royston. Though the conspirators were made aware, through a servant of Lord Mounteagle, of the discovery which had been made, they nevertheless, by a singular infatuation, continued their preparations, in the hope that the true nature of their scheme had not been unfolded. In this delusion it seems to have been the policy of the government to maintain them to the last. Even after Suffolk, the lord chamberlain, and Lord Mounteagle had actually, on the afternoon of Monday the 4th November, visited the cellar beneath the House of Lords, and there discovered in a corner Guy Fawkes, who pretended to be a servant of Mr. Percy, the tenant of the vault, it was still determined to persist in the undertaking. At two o'clock the following morning, a party of soldiers under the command of Sir Thomas Knevett, a Westminster magistrate, visited the cellar, seized Fawkes at the door, and carried him off to Whitehall, where, in the royal bedchamber, he was interrogated by the king and council, and from thence was conveyed to the Tower. It is needless to pursue further in detail the history of the Gunpowder Plot. On hearing of Fawkes's arrest, the remaining conspirators, with the exception of Tresham, fled from London to the place of rendezvous in Warwickshire, in the desperate hope of organising an insurrection. But such an expectation was vain. Pursued by the civil and military authorities, they were overtaken at the mansion of Holbeach, on the borders of Staffordshire, where Catesby and three others, refusing to surrender, were slain. The remainder, taken prisoners in different places, were carried up to London, tried, and condemned with their associate Guy Fawkes, who from having undertaken the office of firing the train of gunpowder, came to be popularly regarded as the leading actor in the conspiracy. Leniency could not be expected in the circumstances, and all the horrid ceremonies attending the deaths of traitors were observed to the fullest extent. The executions took place on the 30th and 31st of January, at the west end of St. Paul's Churchyard. Some Catholic writers have maintained the whole Gunpowder Plot to be fictitious, and to have been concocted for state purposes by Cecil. But such a supposition is entirely contrary to all historical evidence. There cannot be a shadow of a doubt, that a real and dangerous conspiracy was formed; that it was very nearly successful; and that the parties who suffered death as participators in it, received the due punishment of their crimes. At the same time, it cannot be denied that a certain amount of mystery envelops the revelation of the plot, which in all probability will never be dispelled. GUY FAWKE'S DAYTill lately, a special service for the 5th of November formed part of the ritual of the English Book of Common Prayer; but by a recent ordinance of the Queen in Council, this service, along with those for the Martyrdom of Charles I, and the Restoration of Charles II, has been abolished. The appointment of this day, as a holiday, dates from an enactment of the British parliament passed in January 1606, shortly after the narrow escape made by the legislature from the machinations of Guy Fawkes and his confederates.  That the gunpowder treason, however, should pass into oblivion is not likely, as long as the well-known festival of Guy Fawkes's Day is observed by English juveniles, who still regard the 5th of November as one of the most joyous days of the year. The universal mode of observance through all parts of England, is the dressing up of a scare-crow figure, in such cast-habiliments as can be procured (the head-piece, generally a paper-cap, painted and knotted with paper strips in imitation of ribbons), parading it in a chair through the streets, and at nightfall burning it with great solemnity in a huge bonfire. The image is supposed to represent Guy Fawkes, in accordance with which idea, it always carries a dark lantern in one hand, and a bunch of matches in the other. The pro-cession visits the different houses in the neighbourhood in succession, repeating the time-honoured rhyme: Remember, remember! The fifth of November, The Gunpowder treason and plot; There is no reason Why the Gunpowder treason Should ever be forgot! Numerous variations and additions are made in different parts of the country. Thus in Islip, Oxfordshire, the following lines, as quoted by Sir Henry Ellis in his edition of Brand's Popular Antiquities, are chanted. The fifth of November, Since I can remember, Gunpowder treason and plot: This is the day that God did prevent, To blow up his king and parliament. A stick and a stake, For Victoria's sake; If you won't give me one, I'll take two: The better for me, And the worse for you. One invariable custom is always maintained on these occasions-that of soliciting money from the passers-by, in the formula, 'Pray remember Guy!' 'Please to remember Guy!' or 'Please to remember the bonfire!' In former times, in London, the burning of the effigy of Guy Fawkes on the 5th of November was a most important and portentous ceremony. The bonfire in Lincoln's Inn Fields was conducted on an especially magnificent scale. Two hundred cart-loads of fuel would sometimes be consumed in feeding this single fire, while upwards of thirty 'Guys' would be suspended on gibbets and committed to the flames. Another tremendous pile was heaped up by the butchers in Clare Market, who on the same evening paraded through the streets in great force, serenading the citizens with the famed 'marrow-bone-and-cleaver' music. The uproar throughout the town from the shouts of the mob, the ringing of the bells in the churches, and the general confusion which prevailed, can but faintly be imagined by an individual of the present day. The ferment occasioned throughout the country by the 'Papal Aggression' in 1850, gave a new direction to the genius of 5th of November revellers. Instead of Guy Fawkes, a figure of Cardinal Wise-man, then recently created 'Archbishop of Westminster' by the pope, was solemnly burned in effigy in London, amid demonstrations which certainly gave little evidence of any revolution in the feelings of the English people towards the Romish see. In 1857, a similar honour was accorded to Nana Sahib, whose atrocities at Cawnpore in the previous month of July, had excited such a cry of horror throughout the civilised world. The opportunity also is frequently seized by many of that numerous class in London, who get their living no one exactly knows how, to earn a few pence by parading through the streets, on the 5th of November, gigantic figures of the leading celebrities of the day. These are sometimes rather ingeniously got up, and the curiosity of the passer-by, who stops to look at them, is generally taxed with the contribution of a copper. THE REVOLUTION OF 1688: POLITICAL SERVILITYOn 5th November 1688, William, Prince of Orange, landed in Torbay, an event which, if we consider the important results by which it was followed, may perhaps be regarded as the most critical of any recorded in English history. It forms the boundary, as it were, between two great epochs-those of arbitrary and constitutional government-for the great Civil War, in the middle of the seventeenth century, can scarcely be regarded as more than a spasmodic effort which, carried to excess, overshot the mark, and ended by the re-establishment, for a time, of a sway more odious and intolerable, in many respects, than that whose overthrow had cost so much destruction and bloodshed. We hear much of the folly of King James, and of all the other causes of his dethronement, but nothing of the culpable conduct of large official bodies, and of many individual subjects, who made it their business to encourage him in his sadly erroneous course, and to flatter him into the conviction that he might go any lengths with impunity. About a month before the landing of the Prince of Orange, the lord mayor, aldermen, sheriffs, &c., of the city of London sent the infatuated monarch an address, containing these words: We beg leave to assure your majesty that we shall, with all duty and faithfulness, cheerfully and readily, to the utmost hazard of our lives and fortunes, discharge the trust reposed in us by your majesty, according to the avowed principles of the Church of England, in defence of your majesty and the established government. The lieutenancy of London followed in the same strain: We must confess our lives and fortunes are but a mean sacrifice to such transcendent goodness; but we do assure your majesty of our cheerful offering of both against all your majesty's enemies, who shall disturb your peace upon any pretence whatever. The justices of peace for the county of Cumberland said: The unexpected news of the intended invasion of the Dutch fills us with horror and amazement, that any nation should be so transcendently wicked as groundlessly to interrupt the peace and happiness we have enjoyed; therefore, we highly think it our duty, chiefly at this juncture, to offer our lives and fortunes to your majesty's service, not doubting but a happy success will attend your majesty's arms. And if your majesty shall think fit to display your royal standard, which we heartily wish and hope you'll never have occasion to do, we faithfully do promise to repair to it with our persons and interest. The privy-council of Scotland express themselves thus: He shall on this, as on all other occasions, shew all possible alacrity and diligence in obeying your majesty's commands, and be ready to expose our lives and fortunes in the defence of your sacred majesty, your royal consort, his Royal Highness the Prince of Scotland, &c. Nor were the Scottish peers, spiritual and temporal, behindhand on this occasion, concluding their declaration as follows: Not doubting that God will still preserve and deliver you, by giving you the hearts of your subjects, and the necks of your enemies. To the like effect, there were addresses from Portsmouth, Carlisle, Exeter, &c. Nay, so fond was James of this sort of support to his government, that he was content to receive an address from the company of cooks, in which they applaud his Declaration of Indulgence' to the skies: declaring that it: resembled the Almighty's manna, which suited every man's palate, and that men's different gustos might as well be forced as their different apprehensions about religion. A very short period elapsed before James was made to comprehend, by fatal experience, the value of such addresses, and to discriminate between the voice of the majority of a nation and the debasing servility of a few trimmers and time-servers. ABANDONMENT OF ONE OF THE ROYAL TITLESOn the 5th of November 1800, it was settled by the privy-council, that in consequence of the Irish Union, the royal style and title should be changed on the 1st of January following-namely, from George III, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith;' to 'George III, by the grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith.' And thus the title of king of France, which had been borne by the monarchs of this country for four hundred and thirty-two years-since the forty-third year of the reign of the Third Edward-was ultimately abandoned. It was the Salic law which excluded Edward from the inheritance of France; but Queen Elizabeth claimed the title, nevertheless, asserting, as it is said, that if she could not be queen, she would he king of France. And it is the more singular that Elizabeth should have retained the title, for, in the second year of her reign, it was agreed, in a treaty made between France and England, that the king and queen of France [Francis H. and his consort Mary of Scotland] should not, for the future, assume the title of king or queen of England or Ireland. The abandonment of the title of 'King of France' led to our foreign official correspondence being carried on in the English language instead of in French, as previously had been the custom. A droll story, in connection with this official regulation, is told by an old writer. During the war between England and Spain, in the time of Queen Elizabeth, commissioners were appointed on both sides to treat of peace. The Spanish commissioners proposed that the negotiations should be carried on in the French tongue, observing sarcastically, that 'the gentlemen of England could not be ignorant of the language of their fellow-subjects, their queen being queen of France as well as of England.' 'Nay, in faith, gentlemen,' drily replied Dr. Dale, one of the English commissioners, ' the French is too vulgar for a business of this importance; we will therefore, if you please, rather treat in Hebrew, the language of Jerusalem, of which your master calls himself king, and in which you must, of course, be as well skilled as we are in French.' One of the minor titles held by the kings of England, who were also Electors of Hanover,was very enigmatical to Englishmen, particularly when expressed by the following initials, S.R.I.A.T. Nor even when it was extended thus, Sacri Romani Imperii Archi-Thesaurus, and translated into English as, 'Arch-Treasurer of the Holy Roman Empire,' was it less puzzling to the uninitiated. The arch-treasurership of the German empire, was an office settled upon the electors of Hanover, in virtue of their descent from Frederick, Elector Palatine; but its duties were always performed by deputy. Nor had the deputy any concern in the ordinary administration of the imperial treasury, his duties being confined to processions, coronations, and other great public ceremonies, when he carried a golden crown before the emperor, and distributed money and gold and silver medals among the populace. |