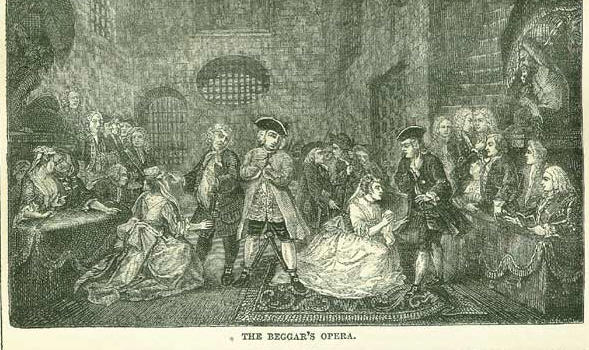

4th MayBorn: Dr. Francis Peck, English historical antiquary, 1692, Stamford, Lincolnshire; John James Audubon, ornithologist, 1782, Louisiana. Died: Edward, Prince of Wales, son of Henry VI, 1471, Tewkesbury; Ulysses Aldovrandi, naturalist, 1605; Louis XIII, King of France, 1643; Dr. Isaac Barrow, eminent English divine, 1677; Sir James Thornhill, painter, 1734; Eustace Budgel, contributor to the Spectator, drowned in the Thames, 1737; Tippoo Sahib, Sultan of Mysore, killed at the siege of Seringapatam, 1799; Sir Robert Kerr Porter, traveller, artist, 1842, St. Petersburg; Horace Twiss, miscellaneous writer, 1849. Feast Day: St. Monica, widow, 387. St. Godard, bishop, 1038. AUDUBONOne of those enthusiasts who devote themselves to one prodigious task, of a respectable, but not remunerative nature, and persevere in it till it, or their life, is finished. He was born of French parents, in the then French colony of Louisiana, in North America, and received a good education at Paris. Settled afterwards by his father on a farm near Philadelphia, he married, engaged in trade, and occasionally cultivated a taste for drawing. Gradually, a love of natural history, and an intense relish for the enjoyment of forest life, led him away from commercial pursuits; and before he was thirty, we find him in Florida, with his rifle and drawing materials, thinking of nothing but how he might capture and sketch the numerous beautiful birds of his native country. At that time, there was a similar enthusiast in the same field, the quondam Scotch pedlar and poet, Alexander Wilson. They met, compared drawings, and felt a mutual respect. Wilson, however, saw in young Audubon' s efforts the promise of a success beyond his own. Years of this kind of life passed over. The stock of drawings increased, notwithstanding the loss at one time of two hundred, containing a thousand subjects, and in time the resolution of publishing was formed. He estimated that the task would occupy him fifteen more years, and he had not one subscriber; but, notwithstanding the painful remonstrances of friends, he persevered. In the course of his preparations, about 1828, he visited London, Edinburgh, and Paris. We remember him at the second of these cities, a hale man of forty-six, nimble as a deer, and with an aquiline style of visage and eye that reminded one of a class of his subjects; a frank, noble, natural man. Professor Wilson took to him wonderfully, and wrote of him, 'The hearts of all are warmed toward Audubon. The man himself is just what you would expect from his productions, full of fine enthusiasm and intelligence, most interesting in his looks and manners, a perfect gentleman, and esteemed by all who know him, for the simplicity and frankness of his nature.' In 1830, he published his first volume, with ninety-nine birds, and one hundred plates. His birds were life-size and colour. The kings of England and France placed their names at the head of his subscription list. He was made a fellow of the Royal Society of London, and member of the Natural History Society of Paris. In 1834, the second volume of the birds of America was published, and then Audubon went to explore the State of Maine, the shores of the Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of St Lawrence, and the Bay of Labrador. In the autumn of 1834, the second volume of Ornithological Biography was published in Edinburgh. People subscribed for the birds of America, with a view to posterity, as men plant trees. Audubon mentions a noble-man in London, who remarked, when subscribing, I may not live to see the work finished, but my children will.' The naturalist, though a man of faith, hope, and endurance, seems to have been afflicted by this remark. 'I thought-what if I should not live to finish my work?' But he comforted himself by his reliance on Providence. After the publication of his third volume, the United States government gave him the use of an exploring vessel, and he went to the coast of Florida and Texas. Three years after this, the fourth volume of his engravings, and the fifth of his descriptions, were published. He had now 435 plates, and 1,165 figures, from the eagle to the humming-bird, with many land and sea views. Audubon never cultivated the graces of style. He wrote to be understood. His descriptions are clear and simple. He describes the mocking-bird with the heart of a poet, and the eye of a naturalist. His description of a hurricane proves that he never ceased to be a careful and accurate observer in the most agitating circumstances. Audubon died at his home, near New York, on the 27th January, 1851. SIR JAMES THORNHILLThis artist was an example of those who are paid for their services, not according to the amount of genius shown, but according to the area covered. His paintings were literally estimated by the square yard, like the work of the bricklayer or plasterer. He generally painted the ceilings and walls of large halls, staircases, and corridors, and was very liberal in his supply of gods and goddesses. Among his works were -the eight pictures illustrating the history of St. Paul, painted in chiaroscuro on the interior of the cupola of St. Paul's Cathedral; the princess' s chamber at Hampton Court; the staircase, a gallery, and several ceilings at Kensington Palace; a hall at Blenheim; the chapel at Wimpole, in Cambridgeshire; and the ceiling of the great hall at Greenwich Hospital. For the pictures at St Paul' s he was paid at the rate of forty shillings per square yard. Walpole, in his 'Anecdotes of Painters,' makes the following observations on the petty spirit in which the payments to Thornhill were made: High as his reputation was, and laborious as his work, he was far from being generously rewarded for some of them; and for others he found it difficult to obtain the stipulated prices. His demands were contested at Greenwich; and though La Fosse received £2,000 for his work at Montague House, and was allowed £500 for his diet besides, Sir James could obtain but forty shillings a square yard for the cupola of St Paul' s, and, I think, no more for Greenwich. When the affairs of the South Sea Company were made up, Thornhill, who had painted their staircase and a little hall, by order of Mr. Knight, their cashier, demanded £1,500; but the directors, hearing that he had been paid only twenty-five shillings a yard for the hall at Blenheim, would allow no more. He had a longer contest with Mr. Styles, who had agreed to give him £3,500 (for painting the saloon at Moor Park); but not being satisfied with the execution, a lawsuit was commenced; and Dahl, Richardson, and others, were appointed to inspect the work. They appeared in court bearing testimony to the merit of the performance; Mr. Styles was condemned to pay the money.' Notwithstanding this mode of paying for works of art by the square yard, Sir James, who was an industrious man, gradually acquired a handsome competency. Artists in our day, who seldom have to work upon ceilings, conduct their labours under easier bodily conditions than Thornhill. It is said that he was so long lying on his back while painting the great hall at Greenwich Hospital, that he could never afterwards sit upright with comfort. TAKING OF SERINGAPATAMOn the 4th of May 1799, Seringapatam was taken, and the empire of Ryder Ally extinguished by the death of his son, the Sultan Tippoo Sahib. The storming of this great fortress by the British troops took place in broad day, and was on that account unexpected by the enemy. The commander, General Sir David Baird, led one of the storming parties in person, with characteristic gallantry, and was the first man after the forlorn hope to reach the top of the breach. So far, well; but when there, he discovered to his surprise a second ditch within, full of water. For a moment he thought it would be impossible to get over this difficulty. He had fortunately, however, observed some workmen' s scaffolding in coming along, and taking this up hastily, was able by its means to cross the ditch; after which all that remained was simply a little hard fighting. Tippoo came forward with apparent gallantry to resist the assailants, and was afterwards taken from under a heap of slain. It is supposed he made this attempt in desperation, having just ordered the murder of twelve British soldiers, which he might well suppose would give him little chance of quarter, if his enemy were aware of the fact. It was remarkable that, fifteen years before, Baird had undergone a long and cruel captivity in this very fort, under Tippoo' s father, Ryder Ally. The hardships he underwent on that occasion were extreme; yet, amidst all his sufferings, he never for a moment lost heart, or ceased to hope for a release. He was truly a noble soldier. As with Wellington, his governing principle was a sense of duty. In every matter, he seemed to be solely anxious to discover what was right to be done, that he might do it. He was a Scotchman, a younger son of Mr. Baird, of Newbyth, in East Lothian (born in 1757, died in 1829). His person was tall and handsome, and his look commanding. In all the relations of his life he was a most worthy man, his kindness of heart winning him the love of all who came in contact with him. An anecdote of Sir David Baird's boyhood forms the key to his character. When a student at Mr. Locie' s Military Academy at Chelsea, where all the routine of garrison duty was kept up, he was one night acting as sentinel. A companion, older than himself, came and desired leave to pass out, that he might fulfil an engagement in London. Baird steadily refused- 'No,' said he, 'that I cannot do; but, if you please, you may knock me down, and walk out over my body.' The taking of Seringapatam gave occasion for a remarkable exercise of juvenile talent in a youth of nineteen, who was studying art in the Royal Academy, and whose name appears in the obituary list at the head of this day. He was then simply Robert Ker Porter, but afterwards, as Sir Robert, became respectfully known for his Travels in Persia; while his two sisters Jane and Anna Maria, attained a reputation as prolific writers of prose fiction. There had been such a thing before as a panorama, or picture giving details of a scene too extensive to be comprehended from one point of view; but it was not a work entitled to much admiration. With marvelous enthusiasm this boy artist began to cover a canvas of two hundred feet long with the scenes attending the capture of the great Indian fort; and, strange to say, he had finished it in six weeks. Sir Benjamin West, President of the Royal Academy, got an early view of the picture, and pronounced it a miracle of precocious talent. When it was arranged for exhibition, vast multitudes both of the learned and the unlearned flocked to see it. I can never forget,' says Dr. Dibdin,' its first impression upon my own mind. It was as a thing dropped from the clouds,-all fire, energy, intelligence, and animation. You looked a second time, the figures moved, and were commingled in hot and bloody fight. You saw the flash of the cannon, the glitter of the bayonet, and the gleam of the falchion. You longed to be leaping from crag to crag with Sir David Baird, who is hallooing his men on to victory I Then again you seemed to be listening to the groans of the wounded and the dying-and more than one female was carried out swooning. The oriental dress, the jewelled turban, the curved and ponderous scimitar-these were among the prime favourites of Sir Robert's pencil, and he treated them with literal truth. The colouring was sound throughout; the accessories strikingly characteristic The public poured in thou-sands for even a transient gaze.' THE BEGGAR'S OPERAIn the spring and early summer of 1728, the Beggar's Opera of Gay had its unprecedented run of sixty-two nights in the theatre of Lincoln's-Inn Fields. No theatrical success of Dryden or Congreve had ever approached this; probably the best of Shakspeare' s fell far short of it. We learn from Spence, that the idea of a play, with malefactors amongst its characters, took its rise in a remark of Swift to Gay, 'What an odd, pretty sort of thing a Newgate pastoral might make.' And, Gay proceeding to work out the idea in the form of a comedy, Swift gave him his advice, and now and then a correction, but believed the piece would not succeed. Congreve was not so sure-he said it would either take greatly or be condemned extremely. The poet, who was in his fortieth year, and had hitherto been but moderately successful in his attempts to please the public, offered the play to Colley Cibber for the Drury Lane Theatre, and only on its being rejected there took it to Mr. Rich, of the playhouse just mentioned, where it was presented for the first time on the 29th of January, 1727-8. Strange to say, the success of the piece was considered doubtful for the greater part of the first act, and was not quite determined till Polly sang her pathetic appeal to her parents, Oh, ponder well, be not severe, To save a wretched wife, For on the rope that hangs my dear Depends poor Polly' s life.  Then the audience, completely captivated, broke out into an applause which established the success of the play. It has ever since been a stock piece of the British stage, notwithstanding questionable morality, and moderate literary merit both in the dialogue and the songs; the fifty beautiful airs introduced into it being what apparently has chiefly given it its hold upon the public. It is to be remarked, that in the same season the play was presented for at least twenty nights in succession at Dublin; and even into Scotland, which had not then one regular theatre, it found its way very soon after. The author, according to usage, got the entire receipts of the third, sixth, ninth, and fifteenth nights, amounting in the aggregate to £693,13s. 6d. In a letter to Swift, he takes credit for having pushed through this precarious affair without servility or flattery; 'and when the play was published, Pope complimented him on not prefacing it with a dedication, thus deliberately foregoing twenty guineas (the established price of such things in those days). So early as the 20th of March, when the piece had only been acted thirty-six times, Mr Rich had profited to the extent of near four thousand pounds. So it might well be said that this play had made Rich gay, and Gay rich. Amongst other consequences of the furore for the play was a sad decline in the receipts at the Italian opera, which Gay had all along meant to rival. The wags had it that that should be called the Beggars' Opera. The king, queen, and princesses came to see the Beggar' s Opera on the twenty-first night of its performance. What was more remarkable, it was honoured on another night with the presence of the prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, whose corrupt practices in the management of a majority in the House of Commons were understood to be glanced at in the dialogues of Peachum and Lockit. Sir Robert, whose good humour was seldom at fault, is said to have laughed heartily at Locicit' s song: When you censure the age, Be cautious and sage, Lest the courtiers offended should be; If you mention vice or bribe, 'Tis so fit to all the tribe, Each cries-That was levelled at me; and so he disarmed the audience. We do not hear much of any of the first actors of the Beggar's Opera, excepting Lavinia Fenton, who personated Polly. She was a young lady of elegant figure, but not striking beauty, a good singer, and of very agreeable conversation and manners. The performance of this part stood out conspicuous in its success, and brought her much notice. Her portrait was published in mezzotint; there was also a memoir of her hitherto obscure life. Her songs were printed on ladies' fans. The fictitious name became so identified with her, that her benefit was announced as Polly's night. One benefit having been given her on the 29th of April, when the Beaux Stratagem was performed, the public were so dissatisfied, that the Beggar' s Opera had to be played for a second benefit to her on the 4th of May. The Duke of Bolton, a nobleman then in the prime of life, living apart from his wife, became inflamed with a violent passion for Miss Fenton, and came frequently to see the play. There is a large print by Hogarth, representing the performance at that scene in Newgate, towards the end of the second act, where Polly kneels to Peachum, to intercede for her husband. There we see two groups of fashionable figures in boxes raised at the sides of the stage; the Duke of Bolton is the nearest on the right hand side, dressed in wig, riband, and star, and with his eyes fixed on the kneeling Polly. At the end of the first season, his grace succeeded in inducing Miss Fenton to leave the stage and live with him, and when the opportunity arrived he married her. She was the first of a series of English actresses who have been raised to a connexion with the peerage. Warton tells us that he knew her, and could testify to her wit, good manners, taste, and intelligence. 'Her conversation,' says he, 'was admired by the first characters of the age, particularly the old Lord. Bathurst and Lord Granville.' Charles, third Duke of Bolton, who married Lavinia Fenton, died in 1754, without legitimate issue, though Miss Fenton had brought him before marriage several children, one of whom, a clergyman, was living in 1809, when Banks mentioned the circumstance in his Extinct Peerage of England. The Bolton peerage fell into this condition in 1794, on the death of Harry, the fifth duke, and thus ended the main line of the Pauletts, so noted as statesmen and public characters in the days of Elizabeth and the first Stuarts. |