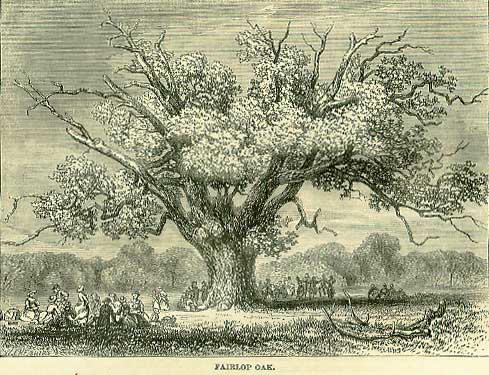

4th JulyBorn: Christian Gellert, German poet and fabulist, 1715, Chemnitz, Saxony. Died: Lord Saye and Seal, beheaded, 1450, London; William Birde, English composer of sacred music, 1623; Meric Casaubon, learned and controversial writer, 1671, bur. Canterbury Cathedral; Henry Bentinck, second Duke of Portland, 1726, Jamaica; Samuel Richardson, novelist, 1761; Fisher Ames, American statesman, President of Harvard College, 1804, Boston, U. S.; Richard Watson, bishop of Llandaff, 1816; John Adams, second president of the United States, 1825; Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States, 1825; Rev. William Kirby, naturalist, 1850, Barham, Suffolk; Richard Grainger, the re-edifier of Newcastle-on-Tyne, 1861, Newcastle. Feast Day: St. Finbar, abbot. St. Bolcan, abbot. St. Sisoes or Sisoy, anchoret in Egypt, about 429. St. Bertha, widow, abbess of Blangy, in Artois, about 725. St. Ulric, bishop of Augsburg, confessor, 973. St. Ode, archbishop of Canterbury, confessor, 10th century. TRANSLATION OF ST. MARTINThat the Church of Rome should not only celebrate the day of St. Martin's death (November 11), but also that of the transference of his remains from their original humble resting place to the cathedral of Tours, shews conclusively the veneration in which this soldier-saint was held. (See under November 11.) The day continues to have a place in the Church of England calendar. In Scotland, this used to be called St. Martin of Bullion's Day, and the weather which prevailed upon it was supposed to have a prophetic character. It was a proverb, that if the deer rise dry and lie down dry on Bullion's Day, it was a sign there would be a good gose-harvest-gose being a term for the latter end of summer; hence gose-harvest was an early harvest. It was believed generally over Europe that rain on this day betokened wet weather for the twenty ensuing days. THOMAS JEFFERSONThe celebrated author of the American Declaration of Independence, entered life as a Virginian barrister, and, while still a young man, was elected a member of the House of Burgesses for his state. When the disputes between the colonies and mother-country began, he took an active part in the measures for the resistance of taxation, and for diffusing the same spirit through the other provinces. Elected in 1775 to the Continental Congress, he zealously promoted the movement for a complete separation from England, and in the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted on the 4th of July 1776, he laid down the pro-positions, since so often quoted, that all men are created equal,' with 'an inalienable right' to 'life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,' and that 'governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.' When the cause of independence became triumphant, Mr. Jefferson naturally took a high place in the administration of the new government. He successively filled the posts of governor of Virginia, secretary of state under the presidency of Washington, and vice-president under that of John Adams; finally, in 1801, attaining to the presidency, which he held for two terms or eight years. While Washington and Adams aimed at a strong, an aristocratic, and a centralising government, Jefferson stood up as the advocate of popular rights and measures. He headed the Liberal Republican, or, as it was afterwards called, the Democratic party. He laboured for civil and religious liberty and education. He secured the prohibition of the slave trade, and of slavery over a vast territory, and was in favour of universal emancipation. In Virginia, he secured the abolition of a religious establishment, and of entails, and the equal rights of both sexes to inheritance. The most important measure of his administration was the acquisition of Louisiana, including the whole territory west of the Mississippi, which was purchased of France for 15,000,000 dollars. His administration was singularly free from political favouritism. It is remembered as one of his sayings, that 'he could always find better men for every place than his own connections.' After retiring from the presidency, he founded the university of Virginia, carried on an extensive correspondence, entertained visitors from all parts of the world, and enjoyed his literary and philosophical pursuits. He was married early in life, and had one daughter, whose numerous children were the solace of his old age. At the age of eighty, he wrote to John Adams, with whom, in spite of political differences, he maintained a warm personal friendship: 'I have ever dreaded a doting age; and my health has been generally so good, and is now so good, that I dread it still. The rapid decline of my strength, during the last winter, has made me hope sometimes that I see land. During summer I enjoy its temperature; but I shudder at the approach of winter, and wish I could sleep through it with the dormouse, and only wake with him in the spring, if ever. They say that Stark could walk about his room. I am told you walk well and firmly. I can only reach my garden, and that with sensible fatigue. I ride, however, daily, but reading is my delight.-God bless you, and give you health, strength, good spirits, and as much life as you think worth having.' The death of Jefferson, at the age of eighty-three, was remarkable. Both he and his friend John Adams, the one the author and the other the chief advocate of the Declaration of Independence-each having filled the highest offices in the Republic they founded-died on the 4th of July 1826, giving a singular solemnity to its fiftieth anniversary. On the tomb of Jefferson, at Monticello, he is described as the author of the Declaration of Independence, the founder of religious freedom in Virginia, and of the university of Virginia; but there is a significant omission of the fact, that he was twice president of the United States. THE FOURTH OF JULYWhere a country or a government has been baffled in its efforts to attain or preserve a hated rule over another people, it must be content to see its failure made the subject of never-ending triumph and exultation. The joy attached to the sense of escape or emancipation tends to perpetuate itself by periodical celebrations, in which it is not likely that the motives of the other party, or the general justice of the case, will be very carefully considered or allowed for. We may doubt if it be morally expedient thus to keep alive the memory of facts which as certainly infer mortification to one party as they do glorification to another: but we must all admit that it is only natural, and in a measure to be expected. The anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, has ever since been celebrated as a great national festival throughout the United States, and wherever Americans are assembled over the world. From Maine to Oregon, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, in every town and village, this birthday of the Republic has always hitherto been ushered in with the ringing of bells, the firing of cannon, the display of the national flag, and other evidences of public rejoicing. A national salute is fired at sunrise, noon, and at sunset, from every fort and man-of-war. The army, militia, and volunteer troops parade, with bands of music, and join with the citizens in patriotic processions. The famous Declaration is solemnly read, and orators, appointed for the occasion, deliver what are termed Fourth of July Orations, in which the history of the country is reviewed, and its past and coming glories pro-claimed. The virtues of the Pilgrim Fathers, the heroic exertions and sufferings of the soldiers of the Revolution, the growth and power of the Republic, and the great future which expands before her, are the staple ideas of these orations. Dinners, toasts, and speeches follow, and at night the whole country blazes with bonfires, rockets, Roman candles, and fireworks of every description. In a great city like New York, Boston, or Philadelphia, the day, and even the night previous, is insufferably noisy with the constant rattle of Chinese-crackers and firearms. In the evening, the displays of fireworks in the public squares, provided by the authorities, are often magnificent. John Adams, second president of the United States, and one of the most distinguished signers of the Declaration of Independence, in a letter written at the time, predicted the manner in which it would be celebrated, and his prediction has doubtless done something to insure its own fulfilment. Adams and Jefferson, two of the signers, both in turn presidents, by a most remarkable coincidence died on the fiftieth anniversary of Independence, in the midst of the national celebration, which, being semi-centennial, was one of extraordinary splendour. THE FAIRLOP OAK FESTIVALThe first Friday in July used to be marked by a local festival in Essex, arising through a simple yet curious chain of circumstances. In Hainault Forest, in Essex, there formerly was an oak of prodigious size, known far and wide as the Fairlop Oak. It came to be a ruin about the beginning of the present century, and in June 1805 was in great part destroyed by an accidental fire. When entire-though the statement seems hardly credible-it is said to have had a girth of thirty-six feet, and to have had seventeen branches, each as large as an ordinary tree of its species. A vegetable prodigy of such a character could not fail to become a most notable and venerated object in the district where it grew. Far back in the last century, there lived an estimable block and pump maker in Wapping, Daniel Day by name, but generally known by the quaint appellative of Good Day. Haunting a small rural retreat which he had acquired in Essex, not far from Fairlop, Mr. Day became deeply interested in the grand old tree above described, and began a practice of resorting to it on the first Friday of July, in order to eat a rustic dinner with a few friends under its branches. His dinner was composed of the good old English fare, beans and bacon, which he never changed, and which no guest ever complained of. Indeed, beans and bacon became identified with the festival, and it would have been an interference with many hallowed associations to make any change or even addition. By and by, the neighbours caught Mr. Day's spirit, and came in multitudes to join in his festivities. As a necessary consequence, trafficking-people came to sell refreshments on the spot; afterwards commerce in hard and soft wares found its way thither; shows and tumbling followed; in short, a regular fair was at last concentrated around the Fairlop Oak, such as Gay describes: Pedlars' stalls with glitt'ring toys are laid, The various fairings of the country-maid. Long silken laces hang upon the twine, And rows of pins and amber bracelets shine. Here the tight lass, knives, combs, and scissors spies, And looks on thimbles with desiring eyes. The mountebank now treads the stage, and sells His pills, his balsams, and his ague-spells: Now o'er and o'er the nimble tumbler springs, And on the rope the vent'rous maiden swings; Jack Pudding, in his party-coloured jacket, Tosses the glove, and jokes at ev'ry packet: Here raree-shows are seen, and Punch's feats, And pockets picked in crowds and various cheats. Mr. Day had thus the satisfaction of introducing the appearances of civilisation in a district which had heretofore been chiefly noted as a haunt of banditti.  Fun of this kind, like fame, naturally gathers force as it goes along. We learn that for some years before the death of Mr. Day, which took lace in 1767, the pump-and-block-makers of Wapping, to the amount of thirty or forty, used to come each first Friday of July to the Fairlop beans-and-bacon feast, seated in a boat formed of a single piece of wood, and mounted upon wheels, covered with an awning, and drawn by six horses. As they went accompanied by a band of musicians, it may be readily supposed how the country-people would flock round, attend, and stare at their anomalous vehicle, as it hurled madly along the way to the forest. A local poet, who had been one of the company, gives us just a faint hint of the feelings connected with this journey: O'er land our vessel bent its course, Guarded by troops of foot and horse; Our anchors they were all a-peak, Our crew were baling from each leak, On Stratford bridge it made me quiver, Lest they should spill us in the river. The founder of the Fairlop Festival was remarkable for benevolence and a few innocent eccentricities. He was never married, but bestowed as much kindness upon the children of a sister as he could have spent upon his own. He had a female servant, a widow, who had been eight-and-twenty years with him. As she had in life loved two things in especial, her wedding ring and her tea, he caused her to be buried with the former on her finger, and a pound of tea in each hand-the latter circumstance being the more remarkable, as he himself disliked tea, and made no use of it. He had a number of little aversions, but no resentments. It changed the usual composed and amiable expression of his countenance to hear of any one going to law. He literally every day relieved the poor at his gate. He often lent sums of money to deserving persons, charging no interest for it. When he had attained a considerable age, the Fairlop Oak lost one of its branches. Accepting the fact as an omen of his own approaching end, he caused the detached limb of the tree to be fashioned into a coffin for himself, and this convenience he took care to try, lest it should prove too short. By his request, his body was borne in its coffin to Barking churchyard by water, in a boat, the worthy old gentleman having contracted a prejudice against all land vehicles, the living horse included, in consequence of being so often thrown from them in his various journeys. BISHOP WATSONRichard Watson was eminent as a prelate, politician, natural philosopher, and controversial theologian; but his popular fame may be said to depend solely on one little book, his Apology for the Bible, written as a reply to Paine's Age of Reason. A curious error has been, more than once, lately promulgated respecting this prelate. At a telegraphic soiree, held in the Free-trade Hall, Manchester, during the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, at that city, in 1861, it was confidently asserted that Bishop Watson had given the first idea of the electric telegraph. The only probable method of accounting for so egregious an error, is that Bishop Watson had been confounded with Sir William Watson, who, when an apothecary in London, conducted some electrical experiments in 1747, and succeeded in sending the electric current from a Leyden jar through a considerable range of earth, or water, and along wires suspended in the open air on sticks. But, even he never had the slightest idea of applying his experiments to telegraphic purposes. In his own account of these experiments, he says: 'If it should be asked to what useful purposes the effects of electricity can be applied, it may be answered that we are not yet so far advanced in these discoveries as to render them conducive to the service of mankind.' Bishop Watson was elected professor of chemistry at the university of Cambridge in 1769; and he gives us the following statement on the subject: 'At the time this honour was conferred upon me, I knew nothing at all of chemistry, had never read a syllable on the subject, nor seen a single experiment in it!' A very fair specimen of the consideration in which physical science was held at the English universities, during the dark ages of the last century. After studying chemistry for fourteen months, Watson commenced his lectures; but in all his printed works on chemistry, and other subjects, the word electricity is never once mentioned! WILLIAM HUTTON'S 'STRONG WOMAN.'William Hutton, the quaint but sensible Birmingham manufacturer, was accustomed to take a month's tour every summer, and to note down his observations on places and people. Some of the results appeared in distinct books, some in his autobiography, and some in the Gentleman's Magazine, towards the close of the last century and the beginning of the present. One year he would be accompanied by his father, a tough old man, who was not frightened at a twenty-mile walk; another year he would go alone; while on one occasion his daughter went with him, she riding on horseback, and he trudging on foot by her side. Various parts of England and Wales were thus visited, at a time when tourists' facilities were slender indeed. It appears from his lists of distances that he could 'do' fifteen or twenty miles a day for weeks together; although his mode of examining places led to a much slower rate of progress. One of the odd characters which he met with at Matlock, in Derbyshire, in July 1801, is worth describing in his own words. After noticing the rocks and caves at that town, he said: 'The greatest wonder I saw was Miss Phoebe Bown, in person five feet six, about thirty, well-proportioned, round-faced and ruddy; a dark penetrating eye, which, the moment it fixes upon your face, stamps your character, and that with precision. Her step (pardon the Irishism) is more manly than a man's, and can easily cover forty miles a day. Her common dress is a man's hat, coat, with a spencer above it, and men's shoes; I believe she is a stranger to breeches. She can lift one hundred-weight with each hand, and carry fourteen score. Can sew, knit, cook, and spin, but hates them all, and every accompaniment to the female character, except that of modesty. A gentleman at the New Bath recently treated her so rudely, that ' she had a good mind to have knocked him down.' She positively assured me she did not know what fear is. She never gives an affront, but will offer to fight any one who gives her one. If she has not fought, perhaps it is owing to the insulter being a coward, for none else would give an affront [to a woman]. She has strong sense, an excellent judgment, says smart things, and supports an easy freedom in all companies. Her voice is more than masculine, it is deep toned; the wind in her face, she can send it a mile; has no beard; accepts any kind of manual labour, as holding the plough, driving the team, thatching the ricks, &c. But her chief avocation is breaking-in horses, at a guinea a week; always rides without a saddle; and is supposed the best judge of a horse, cow, &c., in the country; and is frequently requested to purchase for others at the neighbouring fairs. She is fond of Milton, Pope, Shakspeare, also of music; is self-taught; performs on several instruments, as the flute, violin, harpsichord, and supports the bass-viol in Matlock church. She is an excellent markswoman, and, like her brother-sportsmen, carries her gun upon her shoulder. She eats no beef or pork, and but little mutton; her chief food is milk, and also her drink-discarding wine, ale, and spirits.' |