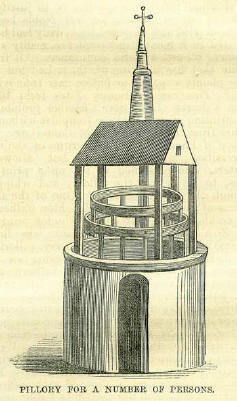

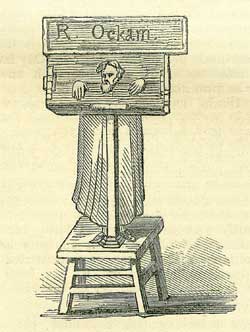

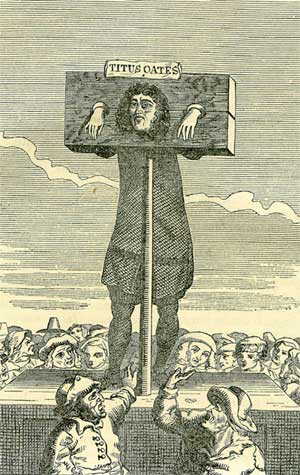

30th JuneDied: Bishop Gavin Dunbar, 1547; Cardinal Baronius, eminent ecclesiastical writer, 1607, Rome; Alexander Brume, poet, 1666; Archibald Campbell, ninth Earl of Argyle, beheaded, 1685, Edinburgh; Sir Thomas Pope Blount, miscellaneous writer, 1697, Tittenhanger; Dr. Thomas Edwards, learned divine, 1785, Nuneaton; Richard Parker, head of the naval mutiny at the Nore, hanged, 1797; Rev. Henry Kett, drowned, 1825; Sultan Mahmoud, of Turkey, 1839; James Silk Buckingham, miscellaneous writer, 1855. Feast Day: St. Paul the Apostle, 68. St. Martial, Bishop of Limoges, 3rd century. MRS. PIOZZIMany people are remembered for the sake of others; their memory survives to after times because of some with whom they were connected, rather than on account of their own peculiar merits. The world is well contented to feed its curiosity with their sayings and doings, in consideration of the influence which they exercised over, or the acquaintance they had with, some one or other of its favourite heroes. Mrs. Thrale-Piozzi, (nèe Hester Salusbury) enjoys this sort of parasitical celebrity. Not that we wish to insinuate that she had not sufficient merit to deserve to be remembered on her own account. A woman of agreeable manners and lively wit, possessed of great personal attractions, if we may not say beauty, she could make no unskilful use of a ready pen, and enjoyed in her own day a literary notoriety. Yet it is not the leader of fashion, nor the star of society, nor the intelligent writer, that the present generation troubles itself to remember, so much as the sprightly hostess and dear intimate friend of Dr. Samuel Johnson. Henry Thrale, Mrs. Thrale's first husband, entertained and commanded the best London society. Engaged in business as a brewer, as his father had been before him, he was, in education, manners, and style of living, a perfect gentleman. Having neglected to avail himself of no advantages which wealth offered, or ambition to rise in the world prompted him to turn to his profit, he contrived to secure his position still more firmly by marrying a lady of good family and fair expectations. There was no passionate attachment in the case; it was a mere matter of business. The lady, indeed, according to her own account, seems scarcely to have been consulted; but, romance set aside, she made a good wife, and he, on the whole, a good husband. Such a wife was a valuable acquisition to Thrale's rising importance; doubtless her wit and spirit were the soul of that motley fashionable group, half literary, half aristocratic, which his wealth and generous hospitality drew together to Streatham. It must have been at one time no small privilege to be a guest at Mrs. Thrale's table. Here was the author of Rasselas, 'facile princeps,' a centre of attraction, flattered and fondled, in spite of his uncouthness and occasional rudeness; here was 'little Burney,' Madame D'Arblay, jotting down notes stealthily for the Diary; here Garrick thought much of himself, as usual, and listened condescendingly to Goldsmith's palaver,' or writhed to hear the plaguy hostess telling how she sat on his knee as a child; here, too, was Bozzy, lively and observing, if not always dignified; here were Reynolds, and Burke, and Langton, and Beauclerk-lords, ladies, and ecclesiastics. Johnson himself was introduced to the Thrales by Arthur Murphy, on the first reasonable pretext which Murphy could frame, and the result gave satisfaction to all parties. The shock of his appearance did not prove too much for them, for the introducer had taken care to give them due warning. Mr. Thrale took to Johnson, and that 'figure large and well formed,' that `countenance of the cast of an ancient statue,' as Boswell has it, gravely humorous, began to appear weekly at Mr. Thrale's table; and when the family removed to Streatham, they persuaded the lexicographer to accompany them, because he was ill, and sadly in want of kind attention. He continued to live with them almost entirely for twenty years, and Mrs. Thrale's good care succeeded at length, as she herself informs us, in restoring him to better health and greater tidiness. Johnson delighted in Mrs. Thrale. He scolded her, or petted her, or paid her compliments, or wrote odes to her, or joined with. her in her pleasant literary labours, according to the form which his solid respect and fatherly affection assumed at any particular time. She gives us a specimen of his friendly flattery-a translation which he made at the moment from a little Italian poem: Long may live my lovely Hetty, Always young, and always pretty; Always pretty, always young, Live my lovely Hetty long; Always young, and always pretty, Long may live my lovely Hetty! After Thrale's death, in 1781, Mrs. Thrale left Streatham, and Johnson had to leave it also. From this time to 1784, though there is evidence of some little unpleasantness having arisen, we find Johnson keeping up a familiar correspondence with the widow, and occasionally in her company. But on June 30th of that year she put his patience and good sense utterly to flight for a time, by informing him that she designed immediately to unite herself to Mr. Piozzi, who had been the music-master of her daughters. He wrote to her in great haste, what she describes afterwards as 'a rough letter,' and certainly it was: 'MADAM,-If I interpret your letter right, you are ignominiously married; if it is yet undone, let us [ ] more [ ] together. If you have abandoned your children and your religion, God forgive your wickedness; if you have forfeited your fame and your country, may your folly do no further mischief. If the last act is yet to do, I, who have loved you, esteemed you, reverenced you, and [-]; I, who long thought you the first of womankind, entreat that, before your fate is irrevocable, I may once more see you. I was, I once was, Madam, 'Most truly yours, 'July 2nd, 1784. 'SAM JOHNSON. I will come down if you permit it.' To this he received a reply: July 4th, 1784. SIR,-I have this morning received from you so rough a letter in reply to one which was both tenderly and respectfully written, that I am forced to desire the conclusion of a correspondence which I can bear to continue no longer. The birth of my second husband is not meaner than that of my first; his sentiments are not meaner, his profession is not meaner, and his superiority in what he professes is acknowledged by all mankind. It is want of fortune, then, that is ignominious; the character of the man I have chosen has no other claim to such an epithet. The religion to which he has always been a zealous adherent will, I hope, teach him to forgive insults he has not deserved; mine will, I hope, enable me to bear them at once with dignity and patience. To hear that I have forfeited my fame is indeed the greatest insult I ever yet received. My fame is as unsullied as snow, or I should think it unworthy of him who must henceforth protect it. I write by the coach, the more speedily and effectually to prevent your coming hither. Perhaps 'by my fame (and I hope it is so) you mean only that celebrity which is a consideration of a much lower kind. I care for that only as it may give pleasure to my husband and his friends. Farewell, dear sir, and accept my best wishes. You have always commanded my esteem, and long enjoyed the fruits of a friendship never infringed by one harsh expression on my part during twenty years of familiar talk. Never did I oppose your will, or control your wish, nor can your unmerited severity itself lessen my regard; but, till you have changed your opinion of Mr. Piozzi, let us converse no more. God bless you. Upon receiving this rejoinder, the old man penned a more amiable epistle, not apologizing, yet, as he says, with tears in his eyes; in answer to which, Mrs. Piozzi informs us, she wrote him a very kind and affectionate farewell,' though she did not see fit to publish it afterwards, as we might have expected. Immediately upon this she went to Italy with her new husband, and Johnson died the same year. It is painful to contemplate such an end to a friendship of twenty years; but with what we now know of the case through the labours of Mr. Hayward, there is no room for hesitation as to which was in the wrong. There had been no cessation of benefits or of friendly feeling from Mrs. Thrale to Johnson up to the moment of his writing her the `rough' letter. The only prompting cause of that letter was that she, the widow of a brewer in good circumstances, was going to gratify a somewhat romantic attachment which she had formed to a man not in any particular inferior to her first husband, except in worldly means. The outrage was as unreasonable in its foundation as it was gross in its style. True, what is called society took the same unfavourable view of Mrs. Thrale's second marriage; but the same society would have continued to smile on Mrs. Thrale as the mistress of Mr. Piozzi, if the sin could only have been tolerably concealed. Society, which admired wealth in a brewer, could see no merit in an Italian gentleman-for such it appears he was-whom poverty condemned to use an honourable and dignifying knowledge for his bread. Was it for a sage like Johnson to endorse the silly disapprobation of such a tribunal, and to insult a woman who for many years had literally nursed him as a daughter would a father? The only true palliation of his offence is to be found-and let us find it-in his age and infirm health. THE PILLORYAn act of the British parliament, dated June 30th, 1837, put an end to the use of the pillory in the United Kingdom, a mode of punishment so barbarous, and at the same time so indefinite in its severity, that we can only wonder it should not have been extinguished long before.  The pillory was for many ages common to most European countries. Known in France as the pillori or carcan, and in Germany as the pranger, it seems to have existed in England before the Conquest in the shape of the stretch-neck, in which the head only of the criminal was confined. By a statute of Edward I it was enacted that every stretch-neck, or pillory, should be made of convenient strength, so that execution might be done upon offenders without peril to their bodies. It usually consisted of a wooden frame erected on a stool, with holes and folding boards for the admission of the head and hands, as shown in the sketch of Robert Ockam undergoing his punishment for perjury in the reign of Henry VIII. In the companion engraving, taken from a MS of the thirteenth century, we have an example of a pillory constructed for punishing a number of offenders at the same time, but this form was of rare occurrence. Rushworth says this instrument was invented for the special benefit of mountebanks and quacks, 'that having gotten upon banks and forms to abuse the people, were exalted in the same kind;' but it seems to have been freely used for cheats of all descriptions. Fabian records that Robert Basset, mayor of London in 1287, 'did sharpe correction upon bakers for making bread of light weight; he caused divers of them to be put in the pillory, as also one Agnes Daintie, for selling of mingled butter.' We find, too, from the Liber Albus, that fraudulent corn, coal, and cattle dealers, cutters of purses, sellers of sham gold rings, keepers of infamous houses, forgers of letters, bonds, and deeds, counterfeiters of papal bulls, users of unstamped measures, and forestallers of the markets, incurred the same punishment. One man was pilloried for pretending to be a sheriff's serjeant, and arresting the bakers of Stratford with the view of obtaining a fine from them for some imaginary breach of the city regulations. Another, for pretending to be the summoner of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and summoning the prioress of Clerkenwell. Other offences, visited in the same way, were playing with false dice, begging under false pretences, decoying children for the purpose of begging and practising soothsaying and magic.  Had the heroes of the pillory been only cheats, thieves, scandalmongers, and perjurers, it would rank no higher among instruments of punishment than the stocks and the ducking stool. Thanks to Archbishop Laud and Star Chamber tyrants, it figured so conspicuously in the political and polemical disputes which heralded the downfall of the monarchy, as to justify a writer of our own time in saying, 'Noble hearts had been tried and tempered in it; daily had been elevated in it mental independence, manly self-reliance, robust, athletic endurance. All from within that has undying worth, it had but the more plainly exposed to public gaze from with-out.' This rise in dignity dates from 1637, when a decree of the Star Chamber prohibited the printing of any book or pamphlet without a license from the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London, or the authorities of the two universities; and ordered all but 'allowed' printers, who presumed to set up a printing press, to be set in the pillory, and whipped through the City of London. One of the first victims of this ordinance was Leighton (father of the archbishop of that name), who for printing his Zion's Plea against Prelacy, was fined £10,000, degraded from the ministry, pilloried, branded, and whipped, besides having an ear cropped, and his nostril slit. Lilburn and Warton were also indicted for unlawfully printing, publishing, and dispersing libellous and seditious works; and upon refusing to appear to answer the interrogatories of the court, were sentenced to pay £500 each, and to be whipped from the Fleet Prison to the pillory at Westminster; a sentence which was carried into execution on the 18th of April 1638. The undaunted Lilburn, when elevated in the pillory, distributed copies of the obnoxious publications, and spoke so boldly against the tyranny of his persecutors, that it was thought necessary to gag him. Prynne, after standing several times in the pillory for having by his denunciations of lady actresses libeled Queen Henrietta by anticipation, solaced his hours of imprisonment by writing his News from Ipswich, by which he incurred a third exposure and the loss of his remaining ear; this was in 1637. He did not suffer alone, Burton and Dr. Bastwick being companions in misfortune with him. The latter's offence consisted in publishing a reply to one Short, directed against the bishops of Rome, and concluding with 'From plague, pestilence, and famine, from bishops, priests, and deacons, good Lord deliver us!' How the two bore their punishment is told in a letter from Garrard to Lord Strafford: In the palace-yard two pillories were erected, and there the sentence of the Star Chamber against Burton, Bastwick, and Prynne was executed. They stood two hours in the pillory. The place was full of people, who cried and howled terribly, especially when Burton was cropped. Dr. Bastwick was very merry; his wife, Dr. Poe's daughter, got on a stool and kissed him. His ears being cut off, she called for them, put them in a clean handkerchief, and carried them away with her. Bastwick told the people the lords had collar-days at court, but this was his collar-day, rejoicing much in it. The sufferers were cheered with the acclamation of the lookers-on, notes were taken of all they said, and manuscript copies distributed through the city. Half a century later, and the once popular informer, Titus Oates, expiated his betrayal of innocent lives in the pillory. Found guilty of perjury on two separate indictments, the inventor of the Popish Plot was condemned in 1685 to public exposure on three consecutive days. The first day's punishment in Palace Yard nearly cost the criminal his life; but his partisans mustered in such force in the city on the succeeding day that they were able to upset the pillory, and nearly succeeded in rescuing their idol from the hands of the authorities. According to his sentence, Oates was to stand every year of his life in the pillory on five different days: before the gate of Westminster Hall on the 9th of August, at Charing Cross on the 10th, at the Temple on the 11th, at the Royal Exchange on the 2nd of September, and at Tyburn on the 24th of April; but, fortunately for the infamous creature, the Revolution deprived his determined enemies of power, and turned the criminal into a pensioner on Government. The next famous sufferer at the pillory was a man of very different stamp. In 1703, the Government offered a reward of fifty pounds for the apprehension of a certain spare, brown-complexioned hose-factor, the author of a scandalous and seditious pamphlet, entitled The Shortest Way with the Dissenters. Rather than his printer and publisher should suffer in his stead, honest Daniel Defoe gave himself up, and was sentenced to be pilloried three times; and on the 29th of July the daring satirist stood unabashed, but not carless, on the pillory in Cheapside-the punishment being repeated two days afterwards in the Temple, where a sympathizing crowd flung garlands, instead of rotten eggs and garbage, at the stout-hearted pamphleteer, drank his health with acclamations, while his noble Hymn to the Pillory was passed from hand to hand, and many a voice recited the stinging lines: Tell them the men that placed him here Are scandals to the times; Are at a loss to find his guilt, And can't commit his crimes! Even his bitterest foes bear witness to Defoe's triumph. One Tory rhymester exclaims: All round him Philistines admiring stand, And keep their Dagon safe from Israel's hand; They, dirt themselves, protected him from filth, And for the faction's money drank his health. The subjects of this ignominious punishment did not always escape so lightly; when there was nothing to excite the sympathy of the people in their favour-still more when there was something in their case which the people regarded with antipathy and disgust - they ran great danger of receiving severer punishment than the law intended to inflict. In 1756, two thief-takers, named Egan and Salmon, were exposed in Smithfield for perjury, and were so roughly treated by the drovers, that Salmon was severely bruised, and Egan died of the injuries he received. In 1763, a man was killed in a similar way at Bow, and in 1780 a coachman, named Read, died on the pillory at Southwark before his time of exposure had expired. The form of judgment expressed that the offender should be set 'in and upon the pillory;' and in 1759, the sheriff of Middlesex was fined £50 and imprisoned for two months, for not confining Dr. Shebbeare's neck and arms in the pillory, and for allowing the doctor's servant to supply his master with refreshment, and shelter him with an umbrella. A droll circumstance connected with the punishment may here be introduced. A man being condemned to the pillory in or about Elizabeth's time, the foot-board on which he was placed proved to be rotten, and down it fell, leaving him hanging by the neck in danger of his life. On being liberated he brought an action against the town for the insufficiency of its pillory, and recovered damages. We have in our possession a dateless pamphlet (apparently about 1790), entitled A Warning to the Fair Sex, or the Matrimonial Deceiver, being the History of the noted George Miller, who was married to upwards of thirty different women, on purpose to plunder Mein. It gives a detail of the procedure of Mr. Miller, which simply consisted in his addressing a love-letter to his intended victim, seeking an interview, and declaring that since he saw her life was insupportable, unless under the hope of obtaining her affections.  It seldom took more than a week to secure a new wife for this fellow, and usually in three days more he had bagged all her money and deserted her. Most of the thirty wives were servants with accumulations of wages. George at length was prosecuted by an indignant female, possessed of rather more determination than the rest, and his punishment was-the pillory. The frontispiece represents him in this exalted situation, with a crowd of women of the humbler class - his seraglio, we presume - pelting him with mud, which some are seen raking from the kennel. The helpless, miserable expression of the face projected from a board blackened with dirt, entreating mercy from those who had none to give, might have been an admirable subject for Hogarth. In 1814, Lord Cochrane, so unjustly convicted as a party to an attempted fraud on the Stock Exchange, was sentenced to the pillory. His parliamentary colleague, Sir Francis Burdett, told the Government that if that portion of the sentence were carried into effect, he would stand in the pillory by Lord Cochrane's side, and they must be responsible for the consequences. The authorities discreetly took the hint, and con-tented themselves with degrading, fining, and imprisoning the hero. A pillory is still standing at the back of the market-place of Coleshill, Warwickshire, and another lies with the town engine in an unused chancel of Eye Church, Sussex. The latter is said to have been last used in 1813. |