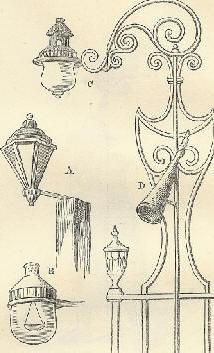

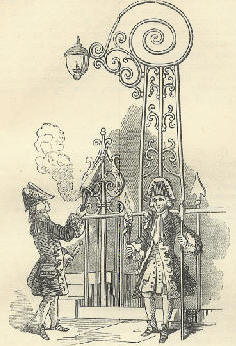

3rd OctoberBorn: Richard Boyle, the great Earl of Cork, 1566, Canterbury; Giovanni Baptista Beccaria, natural philosopher, 1716, Mondovi. Died: Robert Barclay, celebrated Scottish Quaker, author of the Apology for Quaker tenets, 1690, Ury, Kincardineshire; Victor, French dramatic writer, 1846; A. E. Chalon, artist, 1860, London. Feast Day: St. Dionysius the Areopagite, bishop of Athens, martyr, 1st century. The Two Ewalds, martyrs, about 695. St. Gerard, abbot, 959. WATCHING AND LIGHTING OLD LONDONCivilization, in its slowest progress, may be well illustrated by a glance at the past modes of guarding and lighting the tortuous and dangerous streets of old cities. From the year 1253, when Henry III established night-watchmen, until 1830, when Sir Robert Peel's police act established a new kind of guardian, the watchman was little better than a person who: Disturbed your rest to tell you what's o'clock. He had been gradually getting less useful from the days of Elizabeth; thus Dogberry and his troop were unmistakable pictures of the tribe, as much relished for the satirical truth of their delineation in the reign of Anne, as in that of her virgin predecessor. Little improvement took place until the 'Westminster act was passed in 1762, a measure forced on the attention of the legislature by the impunity with which robbery and murder were committed after dark. Before that year, a few wretched oil lamps only served to make darkness visible in the streets, and confuse the wayfarer by partial glimmerings across his ill-paved path. Before the great civil wars, the streets may be said to have been only lighted by chance; by the lights from windows, from lanterns grudgingly hung out by householders, or by the watchmen during their rounds; for by a wonderful stretch of parochial wisdom, and penny-wise economy, the watching and lighting were performed at the same time. The watchman of the olden time carried a fire-pot, called a cresset, on the top of a long pole, and thus marched on, giving light as he bawled the hour, and at the same time, notification of his approach to all thieves, who had thus timeous warning to escape.  The appearance of this functionary in the sixteenth century will be best understood from the engraving here copied from one in Sharp's curious dissertation on the Coventry Mysteries. A similar cresset is still preserved in the armory of the Tower of London. It is an open-barred pot, hanging by swivels fastened to the forked staff; in the center of the pot is a spike, around which was coiled a rope soaked in pitch and rosin, which sputtered and burned with a lurid light, and stinking smoke, as the watchman went his rounds. The watch was established as a stern necessity; and that necessity had become stern, indeed, before his advent. Roger Hoveden has left a vivid picture of London at night in the year 1175, when it was a common practice for gangs of a 'hundred or more in a company' to besiege wealthy houses for plunder, and unscrupulously murder any one who happened to come in their way. Their 'vocation' was so flourishing, that when one of their number was convicted, he had the surpassing assurance to offer the king five hundred pounds of silver for his life. The gallows, however, claimed its due, and made short work with the fraternity; who continued, however, to be troublesome from time to time until Henry III, as already stated, established regular watchmen in all cities and borough-towns, and gave the person plundered by a thief the right of recovering an equivalent for his loss from the legal guardians of the district in which it occurred; a wholesome mode of inflicting a fine for the non-performance of a parish duty.  The London watchman of the time of James I, as here depicted, differed in no essential point from his predecessors in that of Elizabeth. He carried a halbert and a horn-lantern, was well secured in a frieze gabardine, leathern-girdled; and wore a serviceable hat, like a pent-house, to guard against weather. The worthy here depicted has a most venerable face and beard, shewing how ancient was the habit for parish officers to select the poor and feeble for the office of watchman, in order to keep them out of the poorhouse. Such 'ancient and most quiet watchmen' would naturally prefer being out of harm's way, and warn thieves to depart in peace by ringing the bell, that the wether of their flock carried; 'then presently call the rest of the watch together, and thank God you are rid of a knave,' as honest Dogberry advises. Above the head of the man, in the original engraving from which our cut is copied, is inscribed the cry he uttered as he walked the round of his parish. It is this: Lanthorne and a whole candle light, hange out your lights heare! This was in accordance with the old local rule of London, as established by the mayor in 1416, that all householders of the better class, rated above a low rate in the books of their respective parishes, should hang a lantern, lighted with a fresh and whole candle, nightly outside their houses for the accommodation of foot-passengers, from Allhallows evening to Candlemas day. There is another picture of a Jacobean bell-man in the collection of prints in the British Museum, giving a more poetic form to the cry. It runs thus: A light here, maids, hang out your light, And see your horns be clear and bright, That so your candle clear may shine, Continuing from six till nine; That honest men that walk along May see to pass safe without wrong. The honest men had, however, need to be abed betimes, for total darkness fell early on the streets when the rush-candle burned in its socket; and was dispelled only by the occasional appearance of the watchman with his horn lantern; or that more important and noisier official, the bellman. One of these was appointed to each ward, and acted as a sort of inspector to the watchmen and the parish, going round, says Stow, 'all night with a bell, and at every lane's end, and at the ward's end, gave warning of fire and candle, and to help the poor, and pray for the dead.' Our readers have already' been presented with a picture of the Holborn bellman, and a specimen of his verse. He was a regular parish official, visible by day also, advertising sales, crying losses, or summoning to weddings or funerals by ringing his bell. It was the duty of the bellman of St. Sepulchre's parish, near Newgate, to rouse the unfortunates condemned to death in that prison, the night before their execution, and solemnly exhort them to repentance with good words in bad rhyme, ending with: When Sepulchre's bell tomorrow tolls, The Lord above have mercy on your souls! The watchman was a more prosaic individual, never attempting a rhyme; he restricted himself to news of the weather, such as: 'Past eleven, and a starlight night;' or 'Past one o'clock, and a windy morning.' Horace Walpole amusingly narrates the parody uttered by some jesters who returned late from the tavern on the night when frightened Londoners expected the fulfilment of a prophecy, that their city should be engulfed by an earthquake, and had, in consequence, as many of them as could accomplish it, betaken themselves to country lodgings. These revelers, as they passed through the streets, imitated the voice of the watch-men, calling, 'Past twelve o'clock, and a dreadful earthquake!' The miserable inefficiency of the watchmen, and the darkness and danger of the streets, continued until the reign of Anne. The apathy engendered by long usage, at last was roused by the boldness of rascaldom. Robberies occurred on all sides, and night-prowlers scarcely waited for darkness to come, ere they began to plunder. It was not safe to be out after dark, the suburbs were then cut off from the town, and a return from London to Kensington or Highgate was a risk to the purse, and probably to the life of the rash adventurer. There was even a plot concocted to rob Queen Anne as she returned to Kensington in her coach. Still the police continued ineffectual, and as long after as 1744, the mayor and aldermen addressed the king, declaring the streets more unsafe than ever, 'even at such times as were heretofore deemed hours of security;' in consequence of 'confederacies of great numbers of evil-disposed persons armed with bludgeons, pistols, cutlasses, and other dangerous weapons,' who were guilty of the most daring outrages. The prison and the gallows now did their work in clearing the streets, the watch was put on a better footing, and a parish tax for lighting led to the establishment of oil-lamps in the streets.  The rude character of these illuminations may be seen in Hogarth's view of St. James's Street, where the best would naturally be placed. Fig. A of the following group is copied from this view, forming the Lamps background of the fourth plate of the 'Rake's Progress' (1735). A rough wooden post, about eight feet high, is stuck in the ground; from this stretches an iron rod and ring, forming a socket for the angular lamp, dimly lighted by a cotton-wick floating in a small pan of oil. Globular lamps were the invention of one Michael Cole, who obtained a patent for them in 1708, and first exhibited one of them the year following at the door of the St. James's Coffee-house. He described it as 'a new kind of light, composed of one entire glass of a globular shape, with a lamp, which will give a clearer and more certain light from all parts thereof, without any dark shadows, or what else may be confounding or troublesome to the sight, than any other lamps that have hitherto been in use.' Cole was an Irish gentleman, and his lamp seems to have won favor; it slowly, but surely, came into general use. It was customary, in the Hogarthian era, and until the close of the last century, to bestow much cost on the iron-work about aristocratic houses. The lamp-irons at the doors were often of highly-enriched design in wrought metal; many old and curious specimens still remain in the older streets and squares at the west-end of our metropolis. Fig. C depicts one of these in Manchester Square, and the reader will observe the trumpet-shaped implement D attached midway. This is an extinguisher, and its use was to put out the flambeau carried lighted by the footman at the back of the carriage, during a night-progress in the streets. Johnson notices the cowardly bullies of London, who: Their prudent insults to the poor confine; Afar they mark the flambeau's bright approach, And shun the shining train, and golden coach.  We give a second, and more ornate example, of a doorway lamp and extinguisher from Grosvenor Square, and it may be remarked as a curious instance of aristocratic self-sufficiency, that this spot, and a few others inhabited by the nobility, were the last to adopt the use of the gas-lamp. This last great improvement was due to a German named Winser, who first publicly exhibited lamps thus lighted on the colonnade in front of Carlton House. Pall Mall followed the example in 1807. The citizens, some time afterwards, lighted. Bishopsgate Street in the same manner. Awful consequences were predicted by antiquated alarmists from the extensive use of gas in London: it was to poison the air and blow up the inhabitants! In 1736, one thousand dim oil-lamps supplied with light the whole of the city of London, and there was probably a less number outside; now, it is computed there are at least 2000 miles of gas-piping laid under the streets for the supply of our lamps; and their light makes an atmospheric change over London, visible at twenty miles' distance, as if from the reflection of one vast furnace. A KING ARRESTED BY HIS VASSALThe crafty and unscrupulous character of Louis XI is well known. The great object of his policy, as subsequently with Henry VII of England, was the redaction of the power of the nobles and great vassals of the crown, so as to strengthen and render paramount the royal prerogative. But the means which he adopted for the accomplishment of this end were of a much darker and more subtle description than those employed by the English monarch. One feudal prince, against whom his machinations were especially directed, was the celebrated Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, than whom, with his ardent impetuous nature, there can scarcely be imagined a greater contrast than the still and wily Louis, whose line of conduct has earned for him the cognomen of the Tiberius of France. Yet on one occasion, the duplicity of the latter found itself at fault, and nearly entailed upon its possessor the most serious consequences. The burghers of Liege had revolted from their liege lord, the Duke of Burgundy, and been secretly encouraged in their rebellion by the king of France. Louis believed it possible to conceal this circumstance from Charles, but one of his own ministers, the Cardinal Balue, maintained a correspondence with the duke, and kept him informed of everything that transpired at the French court. Through the instigation of this treacherous courtier, Louis was induced to pay his vassal a visit at the town of Peronne, in the territories of the latter. By this mark of confidence, the French king hoped to hoodwink and cajole Charles. The duke received his sovereign with all marks of respect, and lodged him with great splendor in the castle of Peronne. Conferences on state matters were entered into between the two potentates, but in the midst of them Charles received intelligence of Louis's underhand-dealings with the people of Liege, and his rage on learning this was ungovernable. On the 3rd October 1468, he laid the French king under arrest, subjected him to close confinement, and was even on the point of proceeding to further extremities. But he ultimately satisfied himself by dictating to Louis a very humiliating treaty, and causing him to accompany him on an expedition against those very citizens of Liege with whom he had been intriguing, and assist in the burning of their town. It is said that so bitter was the mortification which Louis endured in consequence of having thus imprudently placed himself in the power of Charles, that on his return home, he ordered to be killed a number of tame jays and magpies, who had been taught to cry 'Peronne!' The treachery of Cardinal Balue was also punished by the confinement, for many years, of that churchman in an iron cage of his own invention. ROBERT BARCLAYThough not the founder of the Society of Friends, Robert Barclay was one of its earliest and most energetic champions, and did more than any other in vindicating and explaining its principles to the world. The great apologist of the Quakers was the eldest son of Colonel David Barclay of Ury, in Kincardineshire, a Scottish gentleman of ancient family, who had served with distinction in the wars of the great Gustavus Adolphus. Robert received his first religious training in the strict school of Scottish Calvinism, but having been sent to Paris to study in the Scots College there, under the rectorship of his uncle, he was led to become a convert to the Roman Catholic faith. Returning, in his fifteenth year, to his native country, he found that his father had joined himself to the new sect of the Quakers, which had only a few years previously sprung into existence under the leadership of George Fox. Robert's faith in the Romish church does not appear to have been very lasting, as, in the course of a few years, we find him following the example of his parent, and adopting enthusiastically the same tenets. Father and son had alike to experience the effects of the aversion with which, in its early days, the Society of Friends was regarded both by Cavalier and Puritan, by Presbyterian and Prelatist. The imprisonment which they underwent is said to have been owing to the agency of the celebrated Archbishop Sharp of St. Andrews. It was not, however, of long duration, and through the interposition of the Princess Elizabeth, Princess Palatine, and cousin of Charles II, Robert Barclay was not only liberated from confinement, but seems afterwards to have so far established himself in the favour of the king, that in 1679 he obtained a royal charter erecting his lands of Ury into a free barony, with all the privileges of jurisdiction and otherwise belonging to such an investiture. The remainder of his life was spent in furthering the diffusion of Quakerism, traveling up and down the country in the promulgation of its tenets, and employing his interest with the state authorities in shielding his brethren from persecution. He enjoyed, like Penn, the friendship of James II, and had frequent interviews with him during his visits to London, the last being in 1688, a short time previous to the Revolution. Barclay's own career came to a termination not long afterwards, and he expired prematurely at Ury, after a short illness, on 3rd October 1690, at the age of forty-one. He left, however, a family of seven children, all of whom were living fifty years after his death. One of them, Mr. David Barclay, who became an eminent mercer in Cheapside, is said, as lord mayor, to have entertained three successive English monarchs -George I, II, and III. The celebrated pedestrian and athlete, Captain Barclay, was a descendant of the great Quaker-champion and the last of the name who possessed the estate of Ury. The old mansion house having passed, in 1854, into the hands of strangers, was pulled down, and with it 'the Apologist's Study,' which had remained nearly in the same condition as when used by Barclay, and had formed for generations a favorite object of pilgrimage to the Society of Friends. Barclay's great work, An Apology for the true Christian Divinity, as the same is held forth and practiced by the People called, in scorn, Quakers, was first published in Latin and afterwards translated by the author into English. It comprises an exposition and defence of fifteen religious pro-positions maintained by the Quakers, and forms the ablest and most scholarly defence of their principles that has ever been written. The leading doctrine pervading the book is that of the internal light revealing to man divine truth, which it is contended cannot be attained by any logical process of investigation or reasoning. Among other works of the great Quaker were: A Catechism and Confession of Faith, and A Treatise on Universal Love, the latter being a remonstrance on the criminality of war, and published whilst its author was enduring with his father imprisonment at Aberdeen for conscience' sake. Though so far led away by enthusiasm, on one occasion, as to walk through the streets of Aberdeen, clothed in sack-cloth and ashes, as a call on the inhabitants to repentance, Barclay was far from displaying in his ordinary deportment any of that rigour or sourness by which members of his sect have been often supposed to be characterised. He was exemplary in all the relations of life, and was no less distinguished by the gentleness and amiability of his character, than by range and vigor of intellect. TREATY OF LIMERICKOn 3rd October 1691, was signed the famous treaty of Limerick, by which the resistance of the Irish to the government of William III was terminated, and the latter established as undisputed sovereign of the three kingdoms. On the part of the besieged the defence had been conducted by General Sarsfield, one of the bravest and ablest of King James's commanders, who had conducted thither the remains of the army which had continued undispersed after the disastrous engagement of Aghrim, in the preceding month of July. Within the walls of Limerick were contained the whole strength and hope of the Jacobite cause. On the 26th of August, the town was invested by William's Dutch commander, Ginckel, but the garrison made a brave resistance, and it was not till after some terrible encounters that the attacking force was enabled to open its trenches on both sides of the Shannon. On this advantage being gained, Sarsfield, despairing of successfully holding the place, proposed a surrender upon conditions, an offer which was favorably entertained, and by the treaty signed two days subsequently, the war in Ireland was concluded, and tranquillity restored to the country, after a long series of devastating hostilities. The articles of the treaty of Limerick were highly creditable both to the wisdom and moderation of King William, and also to the valor of the Irish garrison, who had succeeded in obtaining such favorable terms. The troops were allowed to march out of the town with all the honors of war, and had permission, at their option, to embark for France, or enter the service of the English king. The majority, numbering about 10,000, preferred the former alternative, and passing over to the continent, enrolled themselves under the standard of Louis XIV, and became that renowned corps so celebrated in the French service, as 'The Irish Brigade.' The most important stipulation of the treaty, however, in a national point of view, was the clause by which the Roman Catholics were secured in the free exercise of their religion. This stipulation was shamefully violated afterwards by the superimposition of oppressive penal laws, by which was fostered a spirit of hatred and hostility to the English government, who ought rather to have sought to conciliate the inhabitants, and the evil results of whose policy towards Ireland, throughout the eighteenth century, are observable even to the present day. |