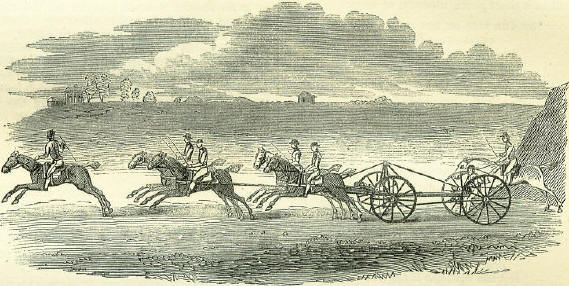

29th AugustBorn: John Locke, philosopher (Essay on the Human Understanding), 1632, Wrinyton, Somersetshire; John Henry Lambert, distinguished natural philosopher of Germany, 1728, Mülhausen. Died: St. John the Baptist, beheaded, 30 A. D.; John Lilburne, zealous parliamentarian, 1657, Eltham; Edmund Hoyle, author of the book on Games, 1769, London; Joseph Wright, historical painter, 1797, Derby; Pope Pius VI, 1799; William Brockedon, painter, 1854. Feast Day: The Decollation of St. John the Baptist. St. Sabina, martyr, 2nd century. St. Sebbi or Sebba, king of Essex, 697. St. Merri or Medericus, abbot of St. Martin's, about 700. LILBURNE THE PAMPHLETEERIn the pamphleteering age of Charles I and the Commonwealth, no man pamphleteered like John Lilburne. The British Museum contains at least a hundred and fifty brochures by him, all written in an exaggerated tone-besides many faceiculi which others wrote in his favour. Lilburne was impartial towards Cavaliers and Roundheads; his great aim was to advance his own opinions and defend himself from the comments which they excited. In 1637, ere the troubles began, Lilburne was accused before the Star-Chamber of publishing and dispersing seditious pamphlets. He refused to take the usual oath in that court, to the effect that he would answer all interrogatories, even though they inculpated himself; and for this refusal he was condemned to be whipped, pilloried, and imprisoned. During the very processes of whipping and pillorying, he harangued the populace against the tyranny of the court-party, and scattered pamphlets from his pocket. The Star-Chamber, which was sitting at that very moment, ordered him to he gagged; but he still stamped and gesticulated, to shew that he would again have harangued the people if he could. The Star-Chamber, more and more provoked, condemned him to be imprisoned in a dungeon and ironed. When the parliament gained ascendency over the king, Lilburne, as well as Prynne, Bastwick, and many other liberals, received their liberty, and were welcomed with joyful acclamations by the people. Then followed the downfall of the king, the Protectorate of Cromwell, and the gradual resuscitation of measures deemed almost as inimical to liberty as those of Charles had been. Lilburne was at his post as usual, fighting the cause of freedom by means of pamphlets, with unquestioned honesty of purpose, but with intemperate zeal. In 1649, he was again thrown into prison, but this time by order of the parliament instead of by that of the crown; even the women of London petitioned for his release, but the parliament was deaf to their arguments. When the case was brought on for regular trial, a London jury found him not guilty of the 'sedition' charged against him by the parliament. Again, after Cromwell had dissolved the Long Parliament, Lilburne was once more imprisoned for his outspoken pamphlets; again was he liberated when the voice of the people obtained expression through the verdict of a jury; and again was there great popular delight displayed at his liberation. There is reason to doubt whether Lilburne was so steady and sagacious a liberal, as to be able to render real services to the cause which he so energetically advocated; but his public life well illustrated the pamphleteering tendencies of the age. One among the pamphlets published in 1653, when Lilburne was opposing the assumption of arbitrary power by Cromwell, was in the form of a pretended catalogue of books, to be sold in 'Little Britain.' First came about forty books, every one with some sarcastic political hit contained in the title. Then came a series of pretended 'Acts and Orders' of parliament, among which the following are samples: And then follow a series of 'Cases of Conscience,' such as the following: It is not stated that these audacious sarcasms were actually by Lilburne, for the pamphlet has neither author nor editor, neither printer nor publisher, named; but they will serve to illustrate the spirit of the times, when such pamphlets could be produced. EDMUND HOYLEOf this celebrated writer of treatises on games of chance, including among others whist, piquet, quadrille, and backgammon, and whose name has become so familiar, as to be immortalised in the well-known proverb, 'According to Hoyle,' little more is known, than that he appears to have been born in 1672, and died in Cavendish Square, London, on 29th August 1769, at the advanced age of ninety-seven. In the Gentleman's Magazine of December 1742, we find among the list of promotions 'Edmund Hoyle, Esq, made by the Primate of Ireland, register of the Prerogative Court, there, worth £600 per annum.' From another source, we learn that he was a barrister by profession. His treatise on Whist, for which the received from the publisher the sum of £1000, was first published in 1743, and attained such a popularity that it ran through five editions in a year, besides being extensively pirated. He has even been called the inventor of the game of whist, but this is certainly a mistake, though there can be no doubt that it was indebted to him for being first treated of, and introduced to the public in a scientific manner. It first began to be popular in England about 1730, when it was particularly studied by a party of gentlemen, who used to assemble in the Crown Coffee House, in Bedford Row. Hoyle is said to have given instructions in the game, for which his charge was a guinea a lesson. BEQUESTS FOR THE GUIDANCE OF TRAVELLERSSome of the old charitable bequests of England form striking memorials of times when travelling, especially at night, and even a night-walk in the streets of a large city, was attended with difficulties unknown to the present generation. For example -the corporation of Woodstock, Oxfordshire, pay ten shillings yearly, the bequest of one Carey, for the ringing of a bell at eight o'clock every evening, for the guide and direction of travellers. By the bequest of Richard Palmer, in 1664, the sexton of Wokingham, Berks, has a sum for ringing every evening at eight, and every morning at four, for this among other purposes, ' that strangers and others who should happen, in winter-nights, within hearing of the ringing of the said bell, to lose their way in the country, might be informed of the time of night, and receive some guidance into the right way.' There is also an endowment of land at Barton, Lincolnshire, and 'the common tradition of the parish is, that a worthy old lady, in ancient times, being accidentally benighted on the Welds, was directed in .her course by the sound of the evening-bell of St. Peter's Church, where, after much alarm, she found herself in safety, and out of gratitude she gave this land to the parish-clerk, on condition that he should ring one of the church bells from seven to eight o'clock every evening, except Sundays, commencing on the day of the carrying of the first load of barley in every year till Shrove Tuesday next ensuing inclusive.' By his will, dated 29th August 1656, John Wardall gave £4 yearly to the churchwardens of St. Botolph's, Billingsgate, 'to provide a good and sufficient iron and glass lanthorn, with a candle, for the direction of passengers to go with more security to and from the water-side, all night long, to be fixed at the north-east corner of the parish church, from the feast-day of St. Bartholomew to Lady-Day; out of which sum £1 was to be paid to the sexton for taking care of the lanthorn.' A similar bequest of John Cooke, in 1662, has provided a lamp-now of gas-at the corner of St. Michael's Lane, next Thames Street. The schoolmaster of the parish of Corstorphine, Edinburghshire, enjoys the profits of an acre of ground on the banks of the Water of Leith, near Coltbridge. This piece of ground is called the Lamp Acre, because it was formerly destined for the support of a lamp in the east end of the church of Corstorphine, believed to have served as 'a beacon to direct travellers going from Edinburgh along a road, which in those times was both difficult and dangerous.' EARL OF MARCH'S CARRIAGE RACE August 29, 1750, there was decided a bet of that original kind for which the noted Earl of March (subsequently fourth Duke of Queensberry) shewed such a genius. It came off at Newmarket at seven o'clock in the morning. The matter undertaken by the earl, in conjunction with the Earl of Eglintorm, on a wager for a thousand guineas against Mr. Theobald Taafe, was to furnish a four-wheeled carriage, with four horses, to be driven by a man, nineteen miles within an hour. A con-temporary authority thus describes the carriage: 'The pole was small, but lapped with fine wire; the perch had a plate underneath; two cords went on each side, from the back-carriage to the fore-carriage, fastened to springs. The harness was of fine leather covered with silk. The seat for the man to sit on was of leather straps, and covered with velvet. The boxes of the wheel were brass, and had tins of oil to drop slowly for an hour. The breechings for the horses were whalebone. The bars were small wood, strengthened with steel springs, as were most parts of the carriage, but all so light, that a man could carry the whole with the harness.' Before this carriage was decided on, several others had been tried. Several horses were killed in the course of the preliminary experiments, which cost in all about seven hundred pounds. The two earls, however, won their thousand guineas, for the carriage performed the distance in 53 minutes 27 seconds, leaving fully time enough to have achieved another mile. LOSS OF THE 'ROYAL GEORGE'Cowper's lines on this disastrous event very well embody the painful feeling which occupied the public mind in reference to it. When Lord Howe's fleet returned to Portsmouth in 1782, after varied service in the Atlantic, it was found that the Royal George, 108 guns, commanded by Admiral Kempenfeldt, required cleaning on the exterior and some repairs near the keel. In order to get at this portion of the hull, the ship was 'heeled over'-that is, thrown so much on one side as to expose a good deal of the other side above the surface of the water. In recent times, the examination is made in a less perilous way; but in those days heeling was always adopted, if the defects were not so serious as to require the ship to go into dock. On the 29th of August, the workmen proceeded to deal with the Royal George in this fashion; but they heeled it over too much, water entered the port-holes, the ship filled, and down she went with all on board-the admiral, captain, officers, crew, about three hundred women and children who were temporarily on board, guns, ammunition, provisions, water, and stores. So sudden was the terrible calamity, that a smaller vessel lying along-side the Royal George was swallowed up in the gulf thus occasioned, and other vessels were placed in imminent danger. Of the total number of eleven hundred souls on board, very nearly nine hundred at once found a watery grave; the rest were saved. The ship had carried the loftiest masts, the heaviest metal, and the greatest number of admirals' flags, of any in the navy; it had been commanded by some of the best officers in the service; and Admiral Kempenfeldt, who was among those drowned, was a general favourite. A court-martial on Captain Waghorn (who had escaped with his life), for negligence in the careening operation, resulted in his acquittal: a liberal subscription for the widows and children of those who had perished; and a monument in Portsea Churchyard to Kempenfeldt and his hapless companions-quickly followed. Cowper mourned over the event in a short poem, monody, or elegy: ON THE LOSS OF THE ROYAL GEORGE (To the March in Scipio.) WRITTEN WHEN THE NEWS ARRIVED Toll for the brave! The brave that are no more! All sunk beneath the wave, Fast by their native shore! Eight hundred of the brave, Whose courage well was tried, Had made the vessel heel, And laid her on her side; A land-breeze shook the shrouds, And she was overset; Down went the Royal George, With all her crew complete. Toll for the brave! Brave Kempenfeldt is gone; His last sea-fight is fought; His work of glory done. It was not in the battle; No tempest gave the shock; She sprang no fatal leak; She ran upon no rock; His sword was in his sheath; His fingers held the pen, When Kempenfeldt went down With twice four hundred men. Weigh the vessel up, Once dreaded by our foes! And mingle with our cup The tear that England owes. Her timbers yet are sound, And she may float again, Full charged with England's thunder, And plough the distant main. But Kempenfeldt is gone; His victories are o'er; And he and his eight hundred men Shall plough the wave no more. Cowper also gave a Latin translation of these stanzas, beginning: Plangimus fortes. Periere fortes, Patrium propter periere littus Bis pater centum; subito sub alto Æquore mersi. The hapless Royal George has been the subject of many interesting submarine operations. During the three months which immediately followed the disaster, several divers succeeded in fishing up sixteen guns out of the ship, by the aid of a diving-bell. In the next year, a projector brought forward a scheme for raising the ship itself; but it failed. In 1817, after the ship had been submerged thirty-five years, it underwent a thorough examination by men who descended in a divines bell. It was found to be little other than a pile of ruinous timber-work-the guns, anchors, spars, and masts having fallen into a confused mass among the timbers. She was too dilapidated to be raised in a body, by any arrangement however ingenious. Twenty-two years afterwards, in 1839, General (then Colonel) Pasley devised a mode of discharging enormous masses of gunpowder, by means of electricity, against the submerged hull, so as to shatter it utterly, to let all the timbers float that would float, and to afford opportunity for divers to bring up the heavier valuables. This plan succeeded completely. Enormous submarine charges of powder, in metal cases containing 2000 lbs. each, were fired, and the anchorage was gradually cleared of an obstruction which had lain there nearly sixty years. The value of the brass guns fished up was equal to the whole cost of the operations. |