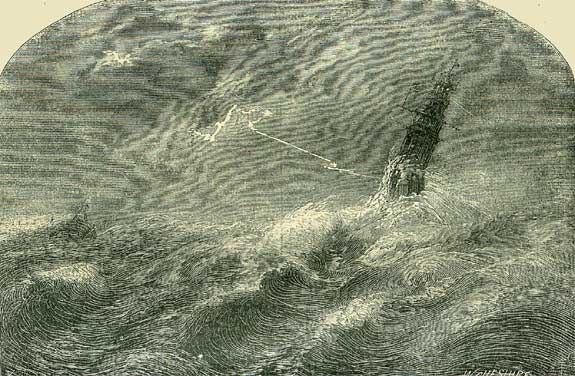

27th NovemberBorn: Francoise d'Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, second consort of Louis XIV, 1635, Niort; Henri Francois d'Aguesseau, chancellor of France, 1668, Limoges; Robert Lowth, bishop of London, biblical critic, 1710; John Murray, publisher, 177S. Died: Horace, lyric and satirical poet, 8 B.C.; Clovis, first king of France, 611, Purls; Maurice, Roman emperor, beheaded at Chalcedon, 602; Louis, Chevalier de Rohan, executed at Paris for conspiracy, 1674; Basil Montagu, Q.C. (writings on philosophical and social questions, he.), 1851, Boulogne. Feast Day: St. James, surnamed Intercisus, martyr, 421. St. Maharsapor, martyr, 421. St. Secundin or Seachnal, bishop of Dunseachlin or Dunsaghlin, in. Meath, 417. St. Maximus, bishop of Riez, confessor, about 460. St. Virgil, bishop of Saltzburg, confessor, 784. ADVENT SUNDAYThe four weeks immediately preceding Christmas are collectively styled Advent, a term denoting approach or arrival, and are so called in reference to the coming celebration of the birth of our Saviour. With this period, the ecclesiastical or Christian year is held to commence, and the first Sunday of these four weeks is termed Advent Sunday, or the first Sunday in Advent. It is always the nearest Sunday to the feast of St. Andrew, whether before or after that day; so that in all cases the season of Advent shall contain the uniform number of four Sundays. In 1864, Advent Sunday falls on the 27th of November, the earliest possible date on which it can occur. THE GREAT STORMEarly on the morning of Saturday, the 27th November 1703, occurred one of the most terrific storms recorded in our national history. It was not merely, as usually happens, a short and sudden burst of tempest, lasting a few hours, but a fierce and tremendous hurricane of a week's duration, which attained its utmost violence on the day above mentioned. The preceding Wednesday was a peculiarly calm, fine day for the season of the year, but at four o'clock in the afternoon a brisk gale commenced, and increased so strongly during the night, that it would have been termed a great storm, if a greater had not immediately followed. On Thursday, the wind slightly abated; but on Friday it blew with redoubled force till midnight, from which time till daybreak on Saturday morning, the tempest was at its extreme height. Consequently, though in some collections of dates the Great Storm is placed under the 26th of November, it actually took place on the following day. Immediately after midnight, on the morning of Saturday, numbers of the affrighted inhabitants of London left their beds, and took refuge in the cellars and lower apartments of their houses. Many thought the end of the world had arrived. Defoe, who experienced the terrors of that dreadful night, says: Horror and confusion seized upon all; no pen can describe it, no tongue can express it, no thought conceive it, unless some of those who were in the extremity of it. It was not till eight o'clock on the Saturday morning, when the storm had slightly lulled, that the boldest could venture forth from the shelter of their dwellings, to seek assistance, or inquire for the safety of friends. The streets were then thickly strewed with bricks, tiles, stones, lead, timber, and all kinds of building materials. The storm continued to rage through the day, with very little diminution in violence, but at four in the afternoon heavy torrents of rain fell, and had the effect of considerably reducing the force of the gale. Ere long, however, the hurricane recommenced with great fury, and in the course of the Sunday and Monday attained such a height, that on Tuesday night few persons dared go to bed. Continuing till noon on Wednesday, the storm then gradually decreased till four in the afternoon, when it terminated in a dead calm, at the very hour of its commencement on the same day of the preceding week. The old and dangerously absurd practice of building chimneys in stacks, containing as many bricks as a modern ordinary sized house, was attended by all its fatal consequences on this occasion. The bills of mortality for the week recorded twenty one deaths in London alone, from the fall of chimneys. After the tempest, houses bore a resemblance to skeletons. Fortunately, three weeks of dry weather followed, permitting the inhabitants to patch up their dwellings with boards, tarpaulins, old sails, and straw; regular repairs being in many instances, at the time, wholly impossible. Plain tiles rose in price from one guinea to six pounds per thousand; and pan tiles from fifty shillings to ten pounds, for the same number. Bricklayers' wages rose in proportion, so that even in the case of large public edit lees, the trustees or managers bestowed on them merely a temporary repair, till prices should fall. During 1701, the Temple, Christ's Hospital, and other buildings in the city of London, presented a remarkable appearance, patched with straw, reeds, and other thatching materials. At Wells, the bishop of that diocese and his wife were killed, when in bed, by a stack of chimneys falling upon them. Defoe, from personal observation, relates that, in the county of Kent alone, 1107 dwelling houses and barns were leveled by the tremendous force of the hurricane. Five hundred grand old trees were prostrated in Penshurst, the ancient park of the Sidneys, and numerous orchards of fruit trees were totally destroyed. The same storm did great damage in Holland and France, but did not extend far to the northward; the border counties and Scotland receiving little injury from it. The loss sustained by the city of London was estimated at one million, and that of Bristol at two hundred thousand pounds. Great destruction of property and loss of life occurred on the river Thames. The worst period of the storm there, was from midnight to daybreak, the night being unusually dark, and the tide extraordinarily high. Five hundred. watermen's wherries, 300 ship boats, and 120 barges were destroyed; the number of persons drowned could never be exactly ascertained, but 22 dead bodies were found and interred. The greatest destruction of shipping, however, took place off the coast, where the fleet, under the command of Sir Cloudesley Shovel, had just returned from the Mediterranean. The admiral, and part of his ships anchored near the Gunfleet, rode out the gale with little damage; but of the vessels lying in the Downs few escaped. Three ships of 70 guns, one of 64, two of 56, one of 46, and several other smaller vessels, were totally destroyed, with a loss of 1500 officers and men, among whom was Rear admiral Beaumont. It may surprise many to learn that the elaborate contrivances for saving life from shipwreck date from no distant period. Even late in the last century, the dwellers on the English coasts considered themselves the lawful heirs of all drowned persons, and held that their first duty in the case of a wreck was to secure, for their own behalf, the property which Providence had thus east on their shores. That they should exert themselves to save the lives of their fellow creatures, thus imperiled, was an idea that never presented itself. Nay, superstition, which ever has had a close connection with self interest, declared it was unlucky to rescue a drowning man from his fate. In the humane endeavour to put an end to this horrible state of matters, Burke, in 1776, brought a bill into parliament, enacting that the value of plundered wrecks should be levied from the inhabitants of the district where the wreck occurred. The country gentlemen, resenting the bill as an attack on their vested interests, vehemently opposed it. The govermment of the day also, requiring the votes of the county members to grant supplies for carrying on the war against the revolted. American colonies, joined in the opposition, and threw out the bill, as Will Whitehead expresses it: To make Squire Boobies willing, To grant supplies at every check, Give them the plunder of a wreck, They'll vote another shilling. This allusion to the change which has taken place in public feeling on the subject of wrecks, was rendered necessary to explain the following incident in connection with the Great Storm. At low water, on the morning after the terrible hurricane, more than two hundred men were discovered on the treacherous footing of the Goodwin Sands, crying and gesticulating for aid, well knowing that in a very short time, when the tide rose, they would inevitably perish. The boatmen were too busy, labouring in their vocation of picking up portable property, to think of saving life. The mayor of Deal, an humble slopseller, but a man of extraordinary humanity for the period, went to the custom house, and begged that the boats belonging to that establishment might be sent out to save some, at least, of the poor men. The custom house officers refused, on the ground that this was not the service for which their boats were provided. The mayor then collected a few fellow tradesmen, and in a short speech so inspired them with his generous emotions, that they seized the custom house boats by force, and, going off to the sands, rescued as many persons as they could from certain death. The shipwrecked men being brought to land, naked, cold, and hungry, what was to be done with them? The navy agent at Deal refused to assist then, his duties being, he said, to aid seamen wounded in battle, not shipwrecked men. The worthy mayor, whose name was Powell, had therefore to clothe and feed these poor fellows, provide them with lodgings, and bury at his own expense some that died. Subsequently, after a long course of petitioning, he was reimbursed for his outlay by government; and this concession was followed by parliament requesting the queen to place shipwrecked seamen in the same category as men killed or wounded in action. The widows and children of men who had perished in the Great Storm, were thus placed on the pension list.  The most remarkable of the many edifices destroyed during that dreadful night was the first Eddystone lighthouse, erected four years previously by an enterprising but incompetent individual, named Winstanley. He had been a mercer in London, and, having acquired wealth, retired to Littlebury, in Essex, where he amused himself with the curious but useless mechanical toys that preceded our modern machinery and engineering, as alchemy and astrology preceded chemistry and astronomy. As a specimen of these, it is related that, in one room of his house, there lay an old slipper, which, if a kick were given it, immediately raised a ghost from the floor; in another room, if a visitor sat down in a seemingly comfortable arm chair, the arms would fly round his body, and detain him a close prisoner, till released by the ingenious inventor. The light horse was just such a specimen of misapplied ingenuity as might have been expected from such an intellect. It was built of wood, and deficient in every element of stability. Its polygonal form rendered it peculiarly liable to be swept away by the waves. It was no less exposed to the action of the wind, from the upper part being ornamented with large wooden candlesticks, and supplied with useless vanes, cranes, and other top hamper, as a sailor would say. It is probable that the design of this singular edifice had been suggested to Winstanley by a drawing of a Chinese pagoda. And this lighthouse, placed on a desolate rock in the sea, was painted with representations of suns and compasses, and mottoes of various kinds; such as Post TENEBRAS LUX, GLORY BE TO God, PAX IN BELLO. The last was probably in allusion to the building's fancied security, amidst the wild war of waters. And that such peace might be properly enjoyed, the lighthouse contained, besides a kitchen and accommodation for the keepers, a stateroom, finely carved and painted, with a chimney, two closets, and two windows. There was also a splendid bedchamber, richly gilded and painted. This is Winstanley's own description, accompanying an engraving of the lighthouse, in which he complacently represents himself fishing from the stateroom window. One would suppose he had designed the building for an eccentric ornament to a garden or a park, were it not that, in his whimsical ingenuity, he had contrived a kind of movable shoot on the top, by which stones could be showered down on any side, on an approaching enemy. Men, who knew by experience the aggressive powers of sea waves, remonstrated with Winstanley, but he declared that he was so well assured of the strength of the building, that he would like to be in it during the greatest storm that ever blew under the face of heaven. The confident architect had, a short time previous to the Great Storm, gone to the lighthouse to superintend some repairs. When the fatal tempest came, it swept the flimsy structure into the ocean, and with it the unfortunate Winstanley, and five other persons who were along with him in the building. There is a curious bit of literary history indirectly connected with the Great Storm. Addison, distressed by indigence, wrote a poem on the victory of Blenheim, in which he thus compares the Duke of Marlborough, directing the current of the great fight, to the Spirit of the Storm: So when an angel, by divine command, With rising tempests shakes a guilty land, Such as of late o'er pale Britannia past, Calm and serene, he drives the furious blast. And pleased th' Almighty's orders to perform, Rides in the whirlwind, and directs the storm. Lord Godolphin was so pleased with this simile, that he immediately appointed Addison to the Commissionership of Appeals, the first public employment conferred on the essayist. CIRCUMSTANCES AT THE DEATH OF THOMAS, LORD LYTTELTONThomas, second Lord Lyttelton, who died November 27, 1779, at the age of thirty five, was as remarkable for his reckless and dissipated life not to speak of impious habits of thought as his father had been for the reverse. One of the wicked actions attributed to him, was the seduction of three Misses Amphlett, who resided near his country residence in Shropshire. He had just returned from Ireland where he left one of these ladies when, residing at his house in Hill Street, Berkeley Square, he was attacked with suffocating fits of a threatening character. According to one account, he dreamed one night that a fluttering bird came to his window, and that presently after a woman appeared to him in white apparel, who told him to prepare for death, as he would not outlive three days. He was much alarmed, and called for his servant, who found him in a profuse perspiration, and to whom he related the circumstance which had occurred. According to another account, from a relative of his lordship, he was still awake when the noise of a bird fluttering at the window called his attention; his room seemed filled with light, and he saw in the recess of the window a female figure, being that of a lady whom he had injured, who, pointing to the clock on the mantel piece, then indicating twelve o'clock, said in a severe tone that, at that hour on the third day after, his life would be concluded, after which she vanished and left the room in darkness. That some such circumstance, in one or other of these forms, was believed by Lord Lyttelton to have occurred, there can be no reasonable doubt, for it left him in a depression of spirits which caused him to speak of the matter to his friends. On the third day, he had a party with him at breakfast, including Lord Fortescue, Lady Flood, and two Misses Amphlett, to whom he remarked: 'If I live over tonight, I shall have jockeyed the ghost, for this is the third day.' The whole party set out in the forenoon for his lordship's country house, Pit Place, near Epsom, where he had not long arrived when he had one of his suffocating fits. Nevertheless, he was able to dine with his friends at five o'clock. By a friendly trick, the clocks throughout the house, and the watches of the whole party, including his lordship's, were put forward half an hour. The evening passed agreeably; the ghostly warning was never alluded to; and Lord Lyttelton seemed to have recovered his usual gaiety. At half past eleven, he retired to his bedroom, and soon after got into bed, where he was to take a dose of rhubarb and mint water. According to the report afterwards given by his valet, he kept every now and then looking at his watch. He ordered his curtains to be closed at the foot. It was now within a minute or two of twelve by his watch: he asked to look at mine, and seemed pleased to find it nearly keep time with his own. His lordship then put both to his ear, to satisfy himself that they went. When it was more than a quarter after twelve by our watches, he said: This mysterious lady is not a true prophetess, I find. When it was near the real hour of twelve, he said: Come, I'll wait no longer; get me my medicine; I'll take it, and try to sleep. Perceiving the man stirring the medicine with a toothpick, Lord Lyttelton scolded him, and sent him away for a teaspoon, with which he soon after returned. He found his master in a fit, with his chin, owing to the elevation of the pillow, resting hard upon his neck. Instead of trying to relieve him, he ran for assistance, and when he came back with the alarmed party of guests, Lord Lyttelton was dead. Amongst the company at Pit Place that day, was Mr. Miles Peter Andrews, a companion of Lord Lyttelton. Having business at the Dartford powder mills, in which he was a partner, he left the house early, but not before he had been pleasingly assured that his noble friend was restored to his usual good spirits. So little did the ghost adventure rest in Mr. Andrews's mind, that he did not even recollect the time when it was predicted the event would take place. He had been half an hour in bed at his partner, Mr. Pigou's house at the mill, when suddenly his curtains were pulled open, and Lord Lyttelton appeared before him at his bedside, in his robe de chambre and night cap. Mr. Andrews looked at him some time, and thought it so odd a freak of his friend, that he began to reproach him for his folly in coming down to Dartford Mills without notice, as he could find no accommodation. However, said he, I'll get up, and see what can be done. He turned to the other side of the bed, and rang the bell, when Lord Lyttelton disappeared. His servant soon after coming in, he inquired: 'Where is Lord Lyttelton?' The servant, all astonishment, declared he had not seen anything of his lordship since they left Pit Place. 'Pshaw! you fool, he was here this moment at my bedside.' The servant persisted that it was not possible. Mr. Andrews dressed himself, and with the assistance of the servants, searched every part of the house and garden; but no Lord Lyttelton was to be found. Still Mr. Andrews could not help believing that Lord Lyttelton had played him this trick, till, about four o'clock the same day, an express arrived to inform him of his lordship's death, and the manner of it. An attempt has been made to invalidate the truth of this recital, but on grounds more than usually weak. It has been surmised that Lord Lyttelton meant to take poison, and imposed the story of the warning on his friends; as if he would have chosen for a concealment of his design, a kind of imposture which, as the opinions of mankind go, is just the most hard of belief. This supposition, moreover, overlooks, and is inconsistent with, the fact that Lord Lyttelton was deceived as to the hour by the tampering with the watches; if he meant to destroy himself, he ought to have done it half an hour sooner. It is further affirmed and the explanation is said to come from Lord Fortescue, who was of the party at Pit Place that the story of the vision took its rise in a recent chase for a lady's pet bird, which Lord Lyttelton declared had been harassingly reproduced to him in his dreams. Lord Fortescue may have been induced, by the usual desire of escaping from a supra natural theory, to surmise that the story had some such foundation; but it coheres with no other facts in the case, and fails to account for the impression on Lord Lyttelton's mind, that he had been warned of his coming death a fact of which all his friends bore witness. On the other hand, we have the Lyttelton family fully of belief that the circumstances were as here related. Dr. Johnson tells us, that he heard it from Lord Lyttelton's uncle, Lord Westcote, and he was therefore willing to believe it. There was, in the Dowager Lady Lyttelton's house, in Portugal Street, Grosvenor Square, a picture which she herself executed in 1780, expressly to commemorate the event; it hung in a conspicuous part of her drawing room. The dove appears at the window, while a ,female figure, habited in white, stands at the foot of the bed, anouncing to Lord Lyttelton his dissolution. Every part of the picture was faithfully designed, after the description given to her by the valet de chambre who attended him, to whom his master related all the circumstances. The evidence of Mr. Andrews is also highly important. Mr. J. W. Croaker, in his notes on Boswell, attests that he had more than once heard Mr. Andrews relate the story, with details substantially agreeing with the recital which we have quoted from the Gentleman's Magazine. He was unquestionably good evidence for what occurred to himself, and he may be considered as not a bad reporter of the story of the ghost of the lady which he had heard from Lord Lyttelton's own mouth. Mr. Croker adds, that Mr. Andrews always told the tale reluctantly, and with an evidently solemn conviction of its truth. On the whole, then, the Lyttelton ghost story may be considered as not only one of the most remarkable from its compound character one spiritual occurrence supporting another but also one of the best authenticated, and which it is most difficult to explain away, if we are to allow human testimony to be of the least value. PITT AND HIS TAXESThe great increase in taxation subsequent to the conclusion of the first American war, is a well known circumstance in modern British history. The national debt, which, previous to the commencement of the Seven Years War in 1755, fell short of £75,000,000, was, through the expenses entailed by that conflict, increased to nearly £129,000,000 at the peace of Paris in 1763, while, twenty years subsequently, at the peace of Versailles, in 1783, the latter amount had risen to upwards of £244,000,000, in consequence of the ill judged and futile hostilities with the North American colonies. When William Pitt, the youngest premier and chancellor of exchequer that England had ever seen, and at the time only twenty four years of age, came into office in December 1783, on the dismissal of the Coalition cabinet, he found the finances in such a condition as to necessitate the imposition of various new taxes, including, among others, the levying of an additional rate on windows, and also of duties on game certificates, hackney coaches, and saddle and race horses. This may be regarded as the commencement of a train of additional burdens on the British nation, which afterwards, during the French war, mounted to such a height, that at the present day it seems impossible to comprehend how our fathers could have supported so crushing a load on their resources. Opposite views prevail as to the expediency of the measures followed by England in 1793, when the country, under the leadership of such champions as Pitt and Burke, drifted into a war with the French republic; a war, however, which, in the conjuncture, of circumstances attending the relations between the two countries, must have almost inevitably taken place, sooner or later. At the present day, indeed, when more liberal and enlightened ideas prevail on international questions, and we have also had the benefit of our fathers experience, such a consummation might possibly have been avoided. Of the straightforwardness and vigorous ability of Pitt throughout his career, there can be no doubt, how-ever one sided he may have been in his political sympathies; and a tribute of respect, though opinions will differ as to its grounds, is undoubtedly due to the pilot that weathered the storm.  The taxes imposed by Pitt, as might have been anticipated, caused no inconsiderable amount of grumbling among the nation at large. This grumbling, in many instances, resolved itself into waggish jests and caricatures. The story of the Edinburgh wit, who wrote 'PITT'S WORK'S', on the walls of the houses where windows had been blocked up by the proprietors in consequence of the imposition of an additional duty, is a well known and threadbare joke. Another jest, which took a practical form, was that concocted by a certain Jonathan Thatcher, who, on 27th November 1784, in defiance of the horse tax, imposed a few months previously by Pitt, rode his cow to and from the market of Stockport. A contemporary caricature, representing that scene, is herewith presented to our readers as a historical curiosity. |