27th MarchBorn: James Keill, mathematician, 1671, Edinburgh, Died: Ptolemy XIII of Egypt, b.c. 47, drowned in the Nile; Pope Clement III, A.D. 1191; Alphonso II (of Castile), 1350, Gibraltar; Pope Gregory XI, 1378; James I, King of England, 1625, Tlaeobalds; Bishop Edward Stillingfleet, polemical writer, 1699, Westminster; Leopold, Duke of Lorraine, 1729, Lunerille; R. C. Carpenter, architect, 1855. Feast Day: St. John, of Egypt, hermit, 394. St. Rupert, or Robert, Bishop of Saltzburg, 718. EASTEREaster, the anniversary of our Lord's resurrection from the dead, is one of the three great festivals of the Christian year,-the other two being Christmas and Whitsuntide. From the earliest period of Christianity down to the pre-sent day, it has always been celebrated by believers with the greatest joy, and accounted the Queen of Festivals. In primitive times it was usual for Christians to salute each other on the morning of this day by exclaiming, 'Christ is risen;' to which the person saluted replied, ' Christ is risen indeed,' or else, ' And hath appeared unto Simon;'-a custom still retained in the Greek Church. The common name of this festival in the East was the Paschal Feast, because kept at the same time as the Pascha, or Jewish passover, and in some measure succeeding to it. In the sixth of the Ancyran Canons it is called the Great Day. Our own name Easter is derived, as some suppose, from Eostre, the name of a Saxon deity, whose feast was celebrated every year in the spring, about the same time as the Christian festival-the name being retained when the character of the feast was changed; or, as others suppose, from Oster, which signifies rising. If the latter supposition be correct, Easter is in name, as well as reality, the feast of the resurrection. Though there has never been any difference of opinion in the Christian church as to why Easter is kept, there has been a good deal as to when it ought to be kept. It is one of the moveable feasts; that is, it is not fixed to one particular day-like Christmas Day, e. g., which is always kept on the 25th of December-but moves backwards or forwards according as the full moon next after the vernal equinox falls nearer or further from the equinox. The rule given at the beginning of the Prayer-book to find Easter is this: 'Easter-day is always the first Sunday after the full moon which happens upon or next after the twenty-first day of March; and if the full moon happens upon a Sunday, Easter-day is the Sunday after.' The paschal controversy, which for a time divided Christendom, grew out of a diversity of custom. The churches of Asia Minor, among whom were many Judaizing Christians, kept their paschal feast on the same day as the Jews kept their passover; i. e. on the 14th of Nisan, the Jewish month corresponding to our March or April. But the churches of the West, remembering that our Lord's resurrection took place on the Sunday, kept their festival on the Sunday following the 14th of Nisan. By this means they hoped not only to commemorate the resurrection on the day on which it actually occurred, but also to distinguish themselves more effectually from the Jews. For a time this difference was borne with. mutual forbearance and charity. And when disputes began to arise, we find that Polycarp, the venerable bishop of Smyrna, when on a visit to Rome, took the opportunity of conferring with Anicetas, bishop of that city, upon the question. Polycarp pleaded the practice of St. Philip and St. John, with the latter of whom he had lived, conversed, and joined in its celebration; while Anicetas adduced the practice of St. Peter and St. Paul. Concession came from neither side, and so the matter dropped; but the two bishops continued in Christian friendship and concord. This was about A.D. 158. Towards the end of the century, however, Victor, bishop of Rome, resolved on compelling the Eastern churches to conform to the Western practice, and wrote an imperious letter to the prelates of Asia, commanding them to keep the festival of Easter at the time observed by the Western churches. They very naturally resented such an interference, and declared their resolution to keep Easter at the time they had been accustomed to do. The dispute hence-forward gathered strength, and was the source of much bitterness during the next century. The East was divided from the West, and all who, after the example of the Asiatics, kept Easter-day on the 14th, whether that day were Sunday or not, were styled Qiccertodecimans by those who adopted the Roman custom. One cause of this strife was the imperfection of the Jewish calendar. The ordinary year of the Jews consisted of 12 lunar months of 292 days each, or of 29 and 30 days alternately; that is, of 354 days. To make up the 11 days' deficiency, they intercalated a thirteenth month of 30 days every third year. But even then they would be in advance of the true time without other intercalations; so that they often kept their passover before the vernal equinox. But the Western Christians considered the vernal equinox the commencement of the natural year, and objected to a mode of reckoning which might sometimes cause them to bold their paschal feast twice in one year and omit it altogether the next. To obviate this, the fifth of the apostolic canons decreed that, ' If any bishop, priest, or deacon, celebrated the Holy Feast of Easter before the vernal equinox, as the Jews do, let him be deposed.' At the beginning of the fourth century, matters had gone to such a length, that the Emperor Constantine thought it his duty to take steps to allay the controversy, and to insure uniformity of practice for the future. For this purpose, he got a canon passed in the great (Ecumenical Council of Nice (A.D. 325), That everywhere the great feast of Easter should be observed upon one and the same day; and that not the day of the Jewish passover, but, as had been generally observed, upon the Sunday afterwards.' And to prevent all future disputes as to the time, the following rules were also laid down: As the Egyptians at that time excelled in astronomy, the Bishop of Alexandria was appointed to give notice of Easter-day to the Pope and other patriarchs. But it was evident that this arrangement could not last long; it was too inconvenient and liable to interruptions. The fathers of the next age began, therefore, to adopt the golden numbers of the Metonic cycle, and to place them in the calendar against those days in each month on which the new moons should fall during that year of the cycle. The Metonie cycle was a period of nineteen years. It had been observed by Meton, an Athenian philosopher, that the moon returns to have her changes on the same month and day of the month in the solar year after a lapse of nineteen years, and so, as it were, to run in a circle. He published his discovery at the Olympic Games, B.C. 433, and the cycle has ever since borne his name. The fathers hoped by this cycle to be able always to know the moon's age; and as the vernal equinox was now fixed to the 21st of March, to find Easter for ever. But though the new moon really happened on the same day of the year after a space of nineteen years as it did before, it fell an hour earlier on that day, which, in the course of time, created a serious error in their calculations. A cycle was then framed at Rome for 84 years, and generally received by the Western church, for it was then thought that in this space of time the moon's changes would return not only to the same day of the month, but of the week also. Wheatley tells us that, 'During the time that Easter was kept according to this cycle, Britain was separated from the Roman empire, and the British churches for some time after that separation continued to keep Easter according to this table of 84 years. But soon after that separation, the Church of Rome and several others discovered great deficiencies in this account, and therefore left it for another which was more perfect.'-Book on the Common Prayer, p. 40. This was the Victorian period of 532 years. But he is clearly in error here. The Victorian period was only drawn up about the year 457, and was not adopted by the Church till the fourth. Council of Orleans, A.D. 541. Now from the time the Romans finally left Britain (A.D. 426), when he supposes both churches to be using the cycle of 84 years, till the arrival of St. Augustine (A.D. 596), the error can hardly have amounted to a difference worth disputing about. And yet the time the Britons kept Easter must have varied considerably from that of the Roman missionaries to have given rise to the statement that they were Quartodecimans, which they certainly were not; for it is a well-known fact that British bishops were at the Council of Nice, and doubtless adopted and brought home with them the rule laid down by that assembly. Dr, Hooke's account is far more probable, that the British and Irish churches adhered to the Alexandrian rule, according to which. the Easter festival could not begin before the 8th of March; while according to the rule adopted at Rome and generally in the West, it began as early as the fifth. 'They (the Celts) were manifestly in error,' he says; 'but owing to the haughtiness with which the Italians had demanded an alteration in their calendar, they doggedly determined not to change.'-Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury, vol. i. p. 14. After a good deal of disputation had taken place, with more in prospect, Oswy, King of Northumbria, determined to take the matter in hand. He summoned the leaders of the contending parties to a conference at Whitby, A.D. 664, at which he himself presided. Colman, bishop of Lindisfarne, represented the British church. The Romish party were headed by Agilbert, bishop of Dorchester, and Wilfrid, a young Saxon. Wilfrid was spokesman. The arguments were characteristic of the age; but the manner in which the king decided irresistibly provokes a smile, and makes one doubt whether he were in jest or earnest. Colman spoke first, and urged that the custom of the Celtic church ought not to be changed, because it had been inherited from their forefathers, men beloved of God, &c. Wilfrid followed: The Easter which we observe I saw celebrated by all at Rome: there, where the blessed apostles, Peter and Paul, lived, taught, suffered, and were buried.' And concluded a really powerful speech with these words: 'And if, after all, that Columba of yours were, which I will not deny, a holy man, gifted with the power of working miracles, is he, I ask, to be preferred before the most blessed Prince of the Apostles, to whom our Lord said, 'Thou art Peter, and upon this rock will I build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it; and to thee will I give the keys of the kingdom of heaven'? The King, turning to Colman, asked him, 'Is it true or not, Colman, that these words were spoken to Peter by our Lord?' Colman, who seems to have been completely cowed, could not deny it. 'It is true, 0 King.' 'Then,' said the King, 'can you shew me any such power given to your Columba? ' Colman answered, ' No.' You are both, then, agreed,' continued the King, are you not, that these words were addressed principally to Peter, and that to him were given the keys of heaven by our Lord?' Both assented. 'Then,' said the King, 'I tell you plainly, I shall not stand opposed to the door-keeper of the kingdom of heaven; I desire, as far as in me lies, to adhere to his precepts and obey his commands, lest by offending him who keepeth the keys, I should, when I present myself at the gate, find no one to open to me.' This settled the controversy, though poor honest Colman resigned his see rather than submit to such a decision. On Easter-day depend all the moveable feasts and fasts throughout the year. The nine Sundays before, and the eight following after, are all de-pendent upon it, and form, as it were, a body-guard to this Queen of Festivals. The nine preceding are the six Sundays in Lent, Quinquagesima, Sexagesima, and Septuagesima; the eight following are the five Sundays after Easter, the Sunday after Ascension Day, Whit Sunday, and Trinity Sunday. EASTER CUSTOMSThe old Easter customs which still linger among us vary considerably in form in different parts of the kingdom. The custom of distributing the 'pace' or 'pasche ege,' which was once almost universal among Christians, is still observed by children, and by the peasantry in Lancashire. Even in Scotland, where the great festivals have for centuries been suppressed, the young people still get their hard-boiled dyed eggs, which they roll about, or throw, and finally eat. In Lancashire, and in Cheshire, Staffordshire, and Warwickshire, and perhaps in other counties, the ridiculous custom of ' lifting' or ' heaving' is practised. On Easter Monday the men lift the women, and on Easter Tuesday the women lift or heave the men. The process is performed by two lusty men or women joining their hands across each other's wrists; then, making the person to be heaved sit down on their arms, they lift him up aloft two or three times, and often carry him several yards along a street. A grave clergyman who happened to be passing through a town in Lancashire on an Easter Tuesday, and having to stay an hour or two at an inn, was astonished by three or four lusty women rushing into his room, exclaiming they had come 'to lift him.' 'To lift me!' repeated the amazed divine; 'what can you mean?' 'Why, your reverence, we're come to lift you, 'cause it's Easter Tuesday.' 'Lift me because it's Easter Tuesday? I don't understand. Is there any such custom here?' 'Yes, to be sure; why, don't you know? all us women was lifted yesterday; and us lifts the men today in turn. And in course it's our reights and duties to lift 'em.' After a little further parley, the reverend traveller compromised with his fair visitors for half-a-crown, and thus escaped the dreaded compliment. In Durham, on Easter Monday, the men claim the privilege to take off the women's shoes, and the next day the women retaliate. Anciently, both ecclesiastics and laics used to play at ball in the churches for tansy-cakes on Eastertide; and, though the profane part of this custom is happily everywhere discontinued, tansy-cakes and tansy-puddings are still favourite dishes at Easter in many parts. In some parishes in the counties of Dorset and Devon, the clerk carries round to every house a few white cakes as an Easter offering; these cakes, which are about the eighth of an inch thick, and of two sizes,-the larger being seven or eight inches, the smaller about five in diameter,-have a mingled bitter and sweet taste. In return for these cakes, which are always distributed after Divine service on Good Friday, the clerk receives a gratuity- according to the circumstances or generosity of the householder. EASTER SUNDAY IN ROME

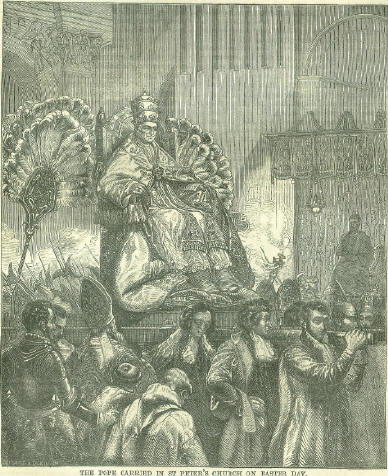

At Rome, as might be expected, Easter Sunday is celebrated with elaborate ceremonials, for which preparations have been making all the previous week. The day is ushered in by the firing of cannons from the castle of St. Angelo, and about 7 o'clock, carriages with ladies and gentlemen are beginning to pour towards St. Peter's. That magnificent basilica is found to be richly decorated for the occasion, the altars are freshly ornamented, and the lights around the tomb and figure of St. Peter are now blazing after their temporary extinction. According to usage, the Pope officiates this day at mass in St. Peter's, and he does so with every imposing accessory that can be devised. From a hall in the adjoining palace of the Vatican, he is borne into the church, under circumstances of the utmost splendour. Seated in his Sedia Gestatoria, his vestments blaze with gold; on his head he wears the Tiara, a tall round gilded cap representing a triple crown, and which is understood to signify spiritual power, temporal power, and a union of both. Beside him are borne the theflabelli, or large fans, composed of ostrich feathers, in which are set the eye-like parts of peacocks' feathers, to signify the eyes or vigilance of the church. Over him is borne a silk canopy richly fringed. After officiating at mass at the high altar, the Pope is, with the same ceremony, and to the sound of music, borne back through the crowded church, and then ascends to the balcony over the central doorway. There rising from his chair of state, and environed by his principal officers, he pronounces a benediction, with indulgences and absolution. This is the most imposing of all the ceremonies at Rome at this season, and the concourse of people in the area in front of St. Peter's is immense. On the occasion in 1862, there were, in addition, at least 10,000 French troops. The crowd is most dense almost immediately below the balcony at which the Pope appears; for there papers are thrown down containing a copy of the prayers that have been uttered, and ordinarily there is a scramble to catch them. The prayers, it need hardly be said, are in Latin. On the evening of Easter Sunday, the dome and other exterior parts of St. Peter's are beautifully illuminated with lamps. THE BIDDENDEN CAKESHasted, in his History of Kent (1790), states that, in the parish of Biddenden, there is an endowment of old, but unknown date, for making a distribution of cakes among the poor every Easter Sunday in the afternoon. The source of the benefaction consists in twenty acres of land, in five parcels, commonly called the Bread and Cheese Lands. Practically, in Mr. Hasted's time, six hundred cakes were thus disposed of, being given to persons who attended service, while 270 loaves of three and a half pounds weight each, with a pound and a half of cheese, were given in addition to such as were parishioners. The cakes distributed on this occasion were impressed with the figures of two females side by side and close together. Amongst the country people it was believed that these figures represented two maidens named Preston, who had left the endowments; and they further alleged that these ladies were twins, who were born in bodily union-that is, joined side to side, as represented on the cakes; who lived nearly thirty years in this connection, when at length one of them died, necessarily causing the death of the other in a few hours. It is thought by the Biddenden people that the figures on the cakes are meant as a memorial of this natural prodigy, as well as of the charitable disposition of the two ladies. Mr. Hasted, however, ascertained that the cakes had only been printed in this manner within the preceding fifty years, and concluded more rationally that the figures were meant to represent two widows, 'as the general objects of a charitable benefaction.' If Mr. Hasted's account of the Biddenden cakes be the true one, the story of the conjoined twins -though not inferring a thing impossible or unexampled-must be set down as one of those cases, of which we find so many in the legends of the common people, where a tale is invented to account for certain appearances, after the real meaning of the appearances was lost. It is a process most natural and simple. First, apparently, some one suggests how the circumstance might be accounted for; next, some one blunderingly states that the circumstance is so accounted for, the only change being one from the subjunctive to the indicative mood. In this way, a vast number of old monuments, and a still greater number of the names of places, come to have grandam tales of the most absurd kind connected with them, as histories of their origin. There is, for example, in the Greyfriars' churchyard, Edinburgh, a mausoleum composed of a recumbent female figure with a pillar-supported canopy over her, on which stand four female figures at the several corners. The popular story is, that the recumbent lady was poisoned by her four daughters, whose statues were afterwards placed over her in eternal remembrance of their wickedness; the fact being, that the four figures were those of Faith, Charity, Justice, &c., favourite emblematical characters in the age when the monument was erected, and the object in placing them there was merely ornamental. About Easter 1333, a curious occurrence took place at Durham. The Queen of Edward III having followed the king to that city, was conducted by him through the gate of the abbey to the prior's lodgings, where, having supped and gone to bed with her royal lord, she was soon disturbed by one of the monks, who readily intimated to the king that St. Cuthbert by no means loved the company of her sex. The queen, upon this, got out of bed, and having hastily dressed herself, went to the castle for the remaining part of the night, asking pardon for the crime she had inadvertently been guilty of against the patron saint of their church. JEMMY CALIBER, ONE OF KING JAMES'S FOOLSDuring his reign in Scotland, King James had a fool or court jester, named Jemmy Camber, who lodged with a laundress in Edinburgh, and was making love to her daughter, when death cut him off in an unexpected and singular manner, as related by Robert Armin in his Nest of Ninnies, published in 1608. The chamberlains was sent to see him there (at the laundress's), who, when he came, found him fast asleepe under the bed stark naked, bathing in nettles, whose skinne when we wakened him was all blistred grievously. The king's chamberlain bid him arise and come to the king. 'I will not,' quoth he, 'I will go make my grave.' See how things chanced; he spake truer than he was aware. For the chamberlaine, going home without him, tolde the king his answere. Jemmy rose, made him ready, takes his horse, and rides to the churchyard in the high towne, where he found the sexton (as the custom is there) making nine graves-three for men, three for women, and three for children; and whoso dyes next, first comes, first served. 'Lend mee thy spade,' says Jemmy, and with that digs a hole, which hole hee bids him make for his grave; and doth give him a French crown; the man, willing to please him (more for his gold than his pleasure), did so; and the foole gets upon his horse, rides to a gentleman of the towne, and on the sodaine within two houres after dyed; of whom the sexton telling, he was buried there indeed. Thus you see, fooles have a guesse at wit sometime, and the wisest could have done no more, nor so much. But thus this fat foole fills a leane grave with his carkasse; upon which grave the king caused a stone of marble to bee put, on which poets writ these lines in remembrance of him: He that gaed all men till jeare, Jemy a Camber he ligges here; Pray for his saule, for he is geane, And here a ligges beneath this steane. |