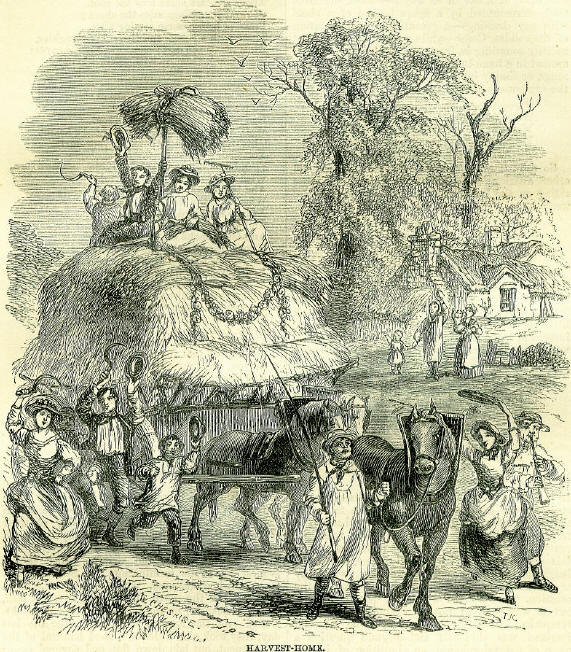

24th SeptemberBorn: Sharon Turner, historian, 1768, London. Died: Pepin, king of France, 768; Michael III, Greek emperor, assassinated, 867; Pope Innocent II, 1143; William of Wykeham, founder of Winchester School, 1404, South Waltham; Samuel Butler, author of Hudibras, 1680, London; Henry, Viscount Hardinge, governor-general and commander in India, 1856, South Park, near Tunbridge. Feast Day: St. Rusticus or Rotiri, bishop of Auvergne, 5th century. St. Chuniald or Conald, priest and missionary. St. Germer or Geremar, abbot, 658. St. Gerard, bishop of Chonad, martyr, 1046. THE FEAST OF THE INGATHERINGWherever, throughout the earth, there is such a thing as a formal harvest, there also appears an inclination to mark it with a festive celebration. The wonder, the gratitude, the piety felt towards the great Author of nature, when it is brought before us that, once more, as it has ever been, the ripening of a few varieties of grass has furnished food for earth's teeming millions, insure that there should every where be some sort of feast of ingathering. In England, this festival passes generally under the endeared name of Harvest-Home. In Scotland, where that term is unknown, the festival is hailed under the name of the Kirn In the north of England, its ordinary designation is the Mell-Supper. And there are perhaps other local names. But every where there is a thankful joy, a feeling which pervades all ranks and conditions of the rural people, and for once in the year brings all upon a level. The servant sympathises with the success of his master in the great labours of the year. The employer looks kindly down upon his toiling servants, and feels it but due to them that they should have a banquet furnished out of the abundance which God has given him-one in which he and his family should join them, all conventional distinctions sinking under the overpowering gush of natural, and, it may be added, religious feeling, which so well befits the time. Most of our old harvest-customs were connected with the ingathering of the crops, but some of their began with the commencement of harvest-work. Thus, in the southern counties, it was customary for the labourers to elect, from among themselves, a leader, whom they denominated their 'lord.' To him all the rest were required to give precedence, and to leave all transactions respecting their work. He made the terms with the farmers for mowing, for reaping, and for all the rest of the harvest-work; he took the lead with the scythe, with the sickle, and on the 'carrying days;' he was to be the first to eat, and the first to drink, at all their refreshments; his mandate was to be law to all the rest, who were bound to address him as 'My Lord,' and to shew him all due honour and respect. Disobedience in any of these particulars was punished by imposing fines according to a scale previously agreed on by 'the lord' and all his vassals. In some instances, if any of his men swore or told a lie in his presence, a fine was inflicted. In Buckinghamshire and other counties, 'a lady' was elected as well as 'a lord,' which often added much merriment to the harvest-season. For, while the lady was to receive all honours due to the lord from the rest of the labourers, he (for the lady was one of the workmen) was required to pass it on to the lord. For instance, at drinking-time, the vassals were to give the horn first to the lady, who passed it to the lord, and when he had drunk, she drank next, and then the others indiscriminately. Every departure from this rule incurred a fine. The blunders which led to fines, of course, were frequent, and produced great merriment.  In the old simple days of England, before the natural feelings of the people had been checked and chilled off by Puritanism in the first place, and what may be called gross Commercialism in the second, the harvest-home was such a scene as Horace's friends might have expected to see at his Sabine farm, or Theocritus described in his Idylls. Perhaps it really was the very same scene which was presented in ancient times. The grain last cut was brought home in its wagon-called the Hock Cart-surmounted by a figure formed of a sheaf with gay dressings-a presumable representation of the goddess Ceres-while a pipe and tabor went merrily sounding in front, and the reapers tripped around in a hand-in-hand ring, singing appropriate songs, or simply by shouts and cries giving vent to the excitement of the day. Harvest-home, harvest-home, We have ploughed, we have sowed, We have reaped, we have mowed, We have brought home every load, Hip, hip, hip, harvest-home! So they sang or shouted. In Lincolnshire and other districts, hand-bells were carried by those riding on the last load, and the following rhymes were sung: The boughs do shake, and the bells do ring, So merrily comes our harvest in, Our harvest in, our harvest in, So merrily comes our harvest in! Hurrah! Troops of village children, who had contributed in various ways to the great labour, joined the throng, solaced with plum-cake in requital of their little services. Sometimes, the image on the cart, instead of being a mere dressed-up bundle of grain, was a pretty girl of the reaping-band, crowned with flowers, and hailed as the Maiden. Of this we have a description in a Ballad of Bloomfield's: Home came the jovial Hockey load, Last of the whole year's crop, And Grace among the green boughs rode, Right plump upon the top. This way and that the wagon reeled, And never queen rode higher; Her cheeks were coloured in the field, And ours before the fire. In some provinces-we may instance Buckinghamshire-it was a favourite practical joke to lay an ambuscade at some place where a high bank or a tree gave opportunity, and drench the hock-cart party with water. Great was the merriment, when this was cleverly and effectively done, the riders laughing, while they shook themselves, as merrily as the rest. Under all the rustic jocosities of the occasion, there seemed a basis of pagan custom; but it was such as not to exclude a Christian sympathy. Indeed, the harvest-home of Old England was obviously and beyond question a piece of natural religion, an ebullition of jocund gratitude to the divine source of all earthly blessings. Herrick describes the harvest-home of his epoch (the earlier half of the seventeenth century) with his usual felicity of expression. Come, sons of summer, by whose toile We are the Lords of wine and oile; By whose tough labours, and rough hands, We rip up first, then reap our lands, Crown'd with the cares of come, now come, And, to the pipe, sing harvest-home. Come forth, my Lord, and see the cart, Drest up with all the country art. See here a maukin, there a sheet As spotlesse pure as it is sweet: The horses, mares, and frisking fillies, Clad, all, in linnen, white as lillies, The harvest swaines and wenches bound For joy, to see the hock-cart crown'd. About the cart heare how the rout Of rural younglings raise the shout; Pressing before, some coming after, Those with a shout, and these with laughter. Some blesse the cart; some kisse the sheaves; Some prank them up with oaken leaves: Some crosse the fill-horse; some with great Devotion stroak the home-borne wheat: While other rusticks, lesse attent To prayers than to merryment, Run after with their breeches rent. Well, on, brave boyes, to your Lord's hearth Glitt'ring with fire, where, for your mirth, You shall see first the large and cheefe Foundation of your feast, fat beefe: With upper stories, mutton, veale, And bacon, which makes full the meale; With sev'rall dishes standing by, As here a custard, there a pie, And here all-tempting frumentie. And for to make the merrie cheere If smirking wine be wanting here, There's that which drowns all care, stout beere, Which freely drink to your Lord's health, Then to the plough, the commonwealth; Next to your flailes, your fanes, your fatts, Then to the maids with wheaten hats; To the rough sickle, and the crookt sythe Drink, frollick, boyes, till all be blythe, Feed and grow fat, and as ye eat, Be mindfull that the lab'ring neat, As you, may have their full of meat; And know, besides, ye must revoke The patient oxe unto the yoke, And all goe back unto the plough And harrow, though they 're hang'd up now. And, you must know, your Lord's word's true, Feed him ye must, whose food fils you. And that this pleasure is like raine, Not sent ye for to drowne your paine. But for to make it spring againe. In the north, there seem to have been some differences in the observance. It was common there for the reapers, on the last day of their business, to have a contention for superiority in quickness of dispatch, groups of three or four taking each a ridge, and striving which should soonest get to its termination. In Scotland, this was called a kemping, which simply means a striving. In the north of England, it was a melt, which, I suspect, means the same thing (from Fr. mêlée). As the reapers went on during the last day, they took care to leave a good handful of the grain uncut, but laid down fiat, and covered over; and, when the field was done, the ' bonniest lass' was allowed to cut this final handful, which was presently dressed up with various sewings, tyings, and trimmings, like a doll, and hailed as a Corn Baby. It was brought home in triumph, with music of fiddles and bagpipes, was set up conspicuously that night at supper, and was usually preserved in the farmer's parlour for the remainder of the year. The bonny lass who cut this handful of grain, was deemed the Har'st Queen. In Hertfordshire, and probably other districts of England, there was the same custom of reserving a final handful; but it was tied up and erected, under the name of a Mare, and the reapers then, one after another, threw their sickles at it, to cut it down. The successful individual called out: 'I have her!' 'What have you?' cried the rest. 'A mare, a mare, a mare!' he replied. 'What will you do with her P' was then asked. 'We'll send her to John Snooks,' or whatever other name, referring to some neighbouring farmer who had not yet got all his grain cut down. This piece of rustic pleasantry was called Crying the Mare. It is very curious to learn, that there used to be a similar practice in so remote a district as the Isle of Skye. A farmer having there got his harvest completed, the last cut handful was sent, under the name of Goabbir Bhacagh (the Cripple Goat), to the next farmer who was still at work upon his crops, it being of course necessary for the bearer to take some care that, on delivery, he should be able instantly to take to his heels, and escape the punishment otherwise sure to befall him. The custom of Crying the Mare is more particularly described by the Rev. C. H. Hartshorne, in his Salopia Antigua (p. 498). 'When a farmer has ended his reaping, and the wooden bottle is passing merrily round, the reapers form themselves into two bands, and commence the following dialogue in loud shouts, or rather in a kind of chant at the utmost pitch of their voice. First band: I have her, I have her, I have her! (Every sentence is repeated three times.) Second: What hast thee? What bast thee? What bast thee? First: A mare, a mare, a mare! Second: Whose is her? Whose is her? Whose is her? First: A. B.'s (naming their master, whose corn is all cut. Second: Where shall we send her? &c. First: To C. D. (naming some neighbour whose corn is still standing). And the whole concludes with a joyous shout of both bands united. In the south-eastern part of Shropshire, the ceremony is performed with a slight variation. The last few stalks of the wheat are left standing; all the reapers throw their sickles, and he who cuts it off, cries: ' I have her, I have her, I have her I' on which the rustic mirth begins; and it is practised in a manner very similar in Devonshire. The latest farmer in the neighbourhood, whose reapers therefore cannot send her to any other person, is said to keep her all the winter. This rural ceremony, which is fast wearing away, evidently refers to the time when, our county lying all open in common fields, and the corn consequently exposed to the depredations of the wild mares, the season at which it was secured from their ravages was a time of rejoicing, and of exulting over a tardier neighbour.' Mr Bray describes the same custom as practised in Devonshire, and the chief peculiarity in that instance is, that the last handful of the standing grain is called the Nack. On this being cut, the reapers assemble round it, calling at the top of their voices, 'Arnack, arnack, arnack! we have'n, we have'n, we have'n,' and the firkin is then handed round; after which the party goes home dancing and shouting. Mr. Bray considers it a relic of Druidism, but, as it appears to us, without any good reason. He also indulges in some needlessly profound speculations regarding the meaning of the words used. 'Arnack' appears to us as simply ' Our nag,' an idea very nearly corresponding to 'the Mare;' and 'we have'n' seems to be merely 'we have him.' In the evening of harvest-home, the supper takes place in the barn, or some other suitable place, the master and mistress generally presiding. This feast is always composed of substantial viands, with an abundance of good ale, and human nature insures that it should be a scene of intense enjoyment. Some one, with better voice than his neighbours, leads off a song of thanks to the host and hostess, in something like the following strain: Here 's a health to our master, The lord of the feast; God bless his endeavours, And send him increase! May prosper his crops, boys, And we reap next year; Here 's our master's good health, boys, Come, drink off your beer! Now harvest is ended, And supper is past Here 's our mistress's health, boys, Come, drink a full glass. For she 's a good woman, Provides us good cheer; Here's your mistress's good health, boys, Come, drink off your beer? One of the rustic assemblage, being chosen to act as 'lord,' goes out, puts on a sort of disguise, and comes in again, crying in a prolonged note, Lar-gess! He and some companions then go about with a plate among the company, and collect a little money with a view to further regalements at the village ale-house. With these, protracted usually to a late hour, the harvest-feast ends. In Scotland, under the name of the Kirn or Kirn Supper (supposed to be from the churn of cream usually presented on the occasion), harvest-home ends in like manner. The description of the feast given by Grahame, in his British Georgics, includes all the characteristic features: The fields are swept, a tranquil silence reigns, And pause of rural labour, far and near. Deep is the morning's hush; from grange to grange Responsive cock-crows, in the distance heard, Distinct as if at hand, soothe the pleased ear; And oft, at intervals, the flail, remote, Sends faintly through the air its deafened sound. Bright now the shortening day, and blithe its close, When to the Kirn the neighbours, old and young, Come dropping in to share the well-earned feast. The smith aside his ponderous sledge has thrown, Raked up his fire, and cooled the hissing brand. His sluice the miller shuts; and from the barn The threshers hie, to don their Sunday coats. Simply adorned, with ribands, blue and pink, Bound round their braided hair, the lasses trip To grace the feast, which now is smoking ranged On tables of all shape, and size, and height, Joined awkwardly, yet to the crowded guests A seemly joyous show, all loaded well: But chief, at the board-head, the haggis round Attracts all eyes, and even the goodman's grace Prunes of its wonted length. With eager knife, The quivering globe he then prepares to broach; While for her gown some ancient matron quakes, Her gown of silken woof, all figured thick With roses white, far larger than the life, On azure ground-her grannam's wedding-garb, Old as that year when Sheriffmuir was fought. Old tales are told, and well-known jests abound, Which laughter meets half-way as ancient friends, Nor, like the worldling, spurns because threadbare. When ended the repast, and board and bench Vanish like thought, by many hands removed, Up strikes the fiddle; quick upon the floor The youths lead out the half-reluctant maids, Bashful at first, and darning through the reels With timid steps, till, by the music cheered, With free and airy step, they bound along, Then deftly wheel, and to their partner's face, Turning this side, now that, with varying step. Sometimes two ancient couples o'er the floor, Skim through a reel, and think of youthful years. Meanwhile the frothing bickers, soon as filled, Are drained, and to the gauntrees oft return, Where gossips sit, unmindful of the dance. Salubrious beverage! Were thy sterling worth But duly prized, no more the alembic vast Would, like some dire volcano, vomit forth Its floods of liquid fire, and far and wide Lay waste the land; no more the fruitful boon Of twice ten shrievedoms, into poison turned, Would taint the very life-blood of the poor, Shrivelling their heart-strings like a burning scroll. Such was formerly the method of conducting the harvest-feast; and in some instances it is still conducted much in the same manner, but there is a growing tendency in the present day, to abolish this method and substitute in its place a general harvest-festival for the whole parish, to which all the farmers are expected to contribute, and which their labourers may freely attend. This festival is usually commenced with a special service in the church, followed by a dinner in a tent, or in some building sufficiently large, and continued with rural sports; and sometimes including a tea-drinking for the women. But this parochial gathering is destitute of one important element in the harvest-supper. It is of too general a character. It provides no particular means for attaching the labourers to their respective masters. If a labourer have any unpleasant feeling towards his master, or is conscious of neglecting his duty, or that his conduct has been offensive towards his master, he will feel ashamed of going to his house to partake of his hospitality, but he will attend without scruple a general feast provided by many contributors, because he will feel under no special obligation to his own master. But if the feast be solely provided by his master, if he receive an invitation from him, if he finds himself welcomed to his house, sits with him at his table, is encouraged to enjoy himself, is allowed to converse freely with him, and treated by him with kindness and cordiality, his prejudices and asperities will be dispelled, and mutual good-will and attachment established. The hospitality of the old-fashioned harvest-supper, and other similar agricultural feasts, was a bond of union between the farmer and his work-people of inestimable value. The only objection alleged against such a feast, is that it often leads to intemperance. So would the harvest-festival, were not regulations adopted to prevent it. If similar regulations were applied to the farmer's harvest-feast, the objection would be removed. Let the farmer invite the clergyman of his parish, and other sober-minded friends, and with their assistance to carry out good regulations, temperance will easily be preserved. The modern harvest-festival, as a parochial thanksgiving for the bounties of Providence, is an excellent institution, in addition to the old harvest-feast, but it should not be considered as a substitute for it. |