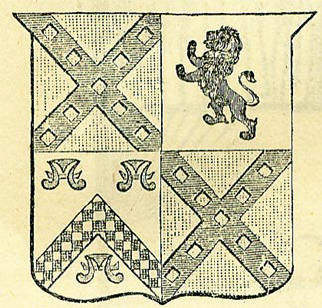

22nd MayBorn: Alexander Pope, 168S, Lombard Street, London; Jonathan Pereira, pharmacologist, 1804, London. Died: Emperor Constantine the Great, 337; Henry VI of England, murdered in the Tower of London, 1471; Robert, Lord Molesworth, 1725; Rev. John Entick, author of Naval History, &c., 1773, Stepney; Jean Baptiste Beccaria, author of a work on crimes and punishments, 1781, Turin; General Duroc, killed at Wurtschen, 1813; Robert Vernon, bequeather of a gallery of pictures to the British nation, 1849, London. Feast Day: Saints Cactus and Æmilius, martyrs, 250 (?). St. Basiliecus, Bishop of Corinna, in Pontius, martyr, 312. St. Conall, abbot. St. Bobo, confessor, 985. St. Yvo, confessor, 1353. TRINITY SUNDAY (1864)The mystery of the Holy Trinity has been from an early date commemorated by a festival, the observance of which is said to have been established in England by Thomas Becket near the close of the twelfth century. In the fact of three hundred and ten churches in England being dedicated to the holy and undivided Trinity, we read the reverence paid to the mystery in mediæval times; but even this is exceeded in our age, when one-fifth of all new churches are so dedicated. Architects and other artists in early times racked their brains for devices expressive of the Three in One, and many very curious ones are preserved. RELICS OF HENRY VIAfter the battle of Hexham (15th May 1464), by which the fortunes of the House of Lancaster were for the time overthrown, the imbecile King Henry VI fled from the field, and for some time was entirely lost to public observation; nor has English history been heretofore very clear as to what for a time became of him. It appears that, in reality, the unfortunate monarch was conducted by some faithful adherents into Yorkshire, and there, in the wild and unfrequented district of Craven, found a temporary and hospitable shelter in Bolton-hall, with Sir Ralph Pudsey, the son-in-law of a gentleman named Tunstall, who was one of the esquires of his body. It was an old and primitive mansion, of the kind long in use among the English squirearchy, having a hall and a few other apartments, forming three irregular sides of a square, which was completed by a screen wall. Remoteness of situation, and not any capacity of defence, must have been what recommended the house as the shelter of a fugitive king. Such as it was, Henry was entertained in it for a considerable time, till at length, tiring of the solitude, and fearful that his enemies would soon be upon him, he chose to leave it, and was soon after seized and carried to the Tower. The family of Pudsey was a hospitable and not over-prudent one. The spacious chimney-breast bore a characteristic legend, 'There ne'er was a Pudsey that increased his estate.' Nevertheless, and though for a number of years out of their old estate and house, the family is still in the enjoyment of both, although not in the person of a male representative. They have for ages preserved certain articles which are confidently understood to have been left by King Henry when he departed from their house. These are, a boot, a glove, and a spoon, all of them having the appearances of great age. Engravings of these objects are here presented, taken from sketches made so long ago as 1777. The boot, it will be observed, has a row of buttons down the side. The glove is of tanned leather, with a lining of hairy deer's skin, turned over. The only remark which the articles suggest is, that King Henry appears to have been a man of effeminate proportions, as we know he was of poor spirit. THE FOUNDER OF THE VERNON GALLERYThe splendid collection of pictures preserved under this name in the South Kensington Museum was collected by a man whose profession suggests very different associations. Robert Vernon had risen from poverty to wealth as a dealer in horses. While practising this trade in a prudent and honourable manner, his natural taste led him to give much thought, as well as money (about £150,000, it was said), to the collection of a gallery of pictures. His pictures were selected by himself alone-with what sound discretion, consummate judgment, and exquisite taste, the Vernon collection still testifies. No greater contrast could possibly be than that between Mr. Vernon and the connoisseur of the last century, represented by the satirist as saying In curious matters I'm exceeding nice, And know their several beauties by their price; Auctions and sales I constantly attend, But choose my pictures by a skilful friend; Originals and copies much the same, The picture's value is the painter's name. As a patron of art, no man has stood so high as Mr. Vernon. He made it an invariable rule never to buy from a picture-dealer, but from the painter himself; thus securing to the latter the full value of his work, and stimulating him, by a higher and more direct motive, to greater exertions. Treating artists as men of genius and high feeling, he never cheapened their productions; though, to a rising young painter, the honour of having a picture admitted into Mr. Vernon's gallery was considered a far greater boon-as a test of merit and promise for the future-than any mere pecuniary consideration could bestow. And Mr. Vernon did not confine his generous spirit to the public patronage of art and artists; it was his pride and pleasure to seek out merit and foster it. Numerous were the instances in which his benevolent mind and princely fortune enabled him to smooth the path of struggling talent, and encourage fainting, toil-worn genius, in its dark hours of depression. In forming his collection, Mr. Vernon's leading idea was to exhibit to future times the best British Art of his period. So it was necessary, as any painter advanced in the practice of his profession, to secure his better productions; consequently from time to time, at a great expenditure of money, Mr. Vernon, as it is termed, weeded his collection; never parting, however, with a picture without commissioning the artist to paint another and more important subject in his improved style. It is not the mere money's worth of Mr. Vernon's munificent gift to the nation that constitutes its real value, but the very peculiar nature of the collection; it being in itself a select illustration of the state and progress of painting in this country from the commencement of the present century. Besides, it is an important nucleus for the formation of a gallery of British Art, both as regards its comprehensiveness and the general excellence of its examples, which are among the masterpieces of their respective painters. And we may conclude in the words of the Times newspaper, by stating that, 'there is nothing in the Vernon collection without its value as a representative of a class of art, and the classes are such that every eminent artist is included.' FIRST CREATION OF BARONETS-MYTHSThe 22nd May 1611 is memorable for the first creation of baronets. It is believed to have been done through the advice of the Earl of Salisbury to his master King James I, as a means of raising money for his majesty's service, the plan being to create two hundred on a payment of £1,000 each. On the king expressing a fear that such a step might offend the great body of the gentry, Salisbury is said to have replied, 'Tush, sire; you want the money: it will do you good; the honour will do the gentry very little harm.' At the same time care was professedly taken that they should all be men of at least a thousand a-year; and the object held out was to raise a band for the amelioration of the province of Ulster--to build towns and churches in that Irish province, and be ready to hazard life in preventing rebel-lion in its native chiefs, each maintaining thirty soldiers for that purpose. One curious little particular about the first batch of eighteen now created was, that to one-Sir Thomas Gerard, of Bryn, Lancashire-the fee of £1,000 was returned, in consideration of his father's great sufferings in the cause of the king's unfortunate mother. From the connexion of the first baronets with Ulster, they were allowed to place in their armorial coat the open red hand heretofore borne by the forfeited O'Neils, the noted Lamh derg Eirin, or red hand of Ulster. This heraldic device, seen in its proper colours on the escutcheons and hatchments of' baronets, has in many instances given rise to stories in which it was accounted for in ways not so creditable to family pride as the possession of land to the extent of £1,000 per annum in the reign of King James. For example, in a painted window of Aston Church, near Birmingham, is a coat-armorial of the Holts, baronets of Aston, containing the red hand, which is accounted for thus. Sir Thomas Holt, two hundred years ago, murdered his cook in a cellar, by running him through with. a spit; and he, though forgiven, and his descendants, were consequently obliged to assume the red hand in the family coat. The picture represents the hand minus a finger, and this is also accounted for. It was believed that the successive generations of the Holts got leave each to take away one finger from the hand, as a step towards the total abolition of the symbol of punishment from the family escutcheon. In like manner, the bloody hand upon a monument in the church of Stoke d'Abernon, Surrey, has a legend connected with. it, to the effect that a gentleman, being out shooting all day with a friend, and meeting no success, vowed he would shoot at the first live thing he met; and meeting a miller, he fired and brought him down dead. The red hand in a hatchment at Wateringbury Church, Kent, and on a table on the hall of Church-Gresly, in Derbyshire, has found similar explanations. Indeed, there is scarcely a baronet's family in the country respecting which this reel hand of Ulster has not been the means of raising some grandam's tale, of which murder and punishment are the leading features.  In the case of the armorial bearings of Nelthorpe of Gray's Inn, co. Middlesex, which is subjoined, the reader will probably acknowledge that, seeing a sword erect in the shield, a second sword held upright in the crest, and a red hand held up in the angle of the shield, nothing could well be more natural, in the absence of better information, than to suppose that some bloody business was hinted at. The fables thus suggested by the red hand of Ulster on the baronets' coats form a good example of a class which we have already done something to illustrate,-those, namely, called myths, which are now generally regarded as springing from a disposition of the human mind to account for actual appearances by some imagined history which the appearances suggest. It may be remarked that, from the disregard of the untutored intellect to the limits of the natural, myths as often transcend their proper bounds as keep within them. Thus, wherever we have a deep, dark, solitary lake, we are sure to find a legend as to a city which it submerges. The city was a sink of wickedness, and the measure of its iniquities was at last completed by its inhospitality to some saint who came and desired a night's lodging in it; whereupon the saint invoked destruction upon it, and the valley presently became the bed of a lake. Fishermen, sailing over the surface in calm, clear weather, sometimes catch the forms of the towers and spires far down in the blue waters, &c. Also, wherever there is an ancient castle ill-placed in low ground, with fine airy sites in the immediate neighbourhood, there do we hear a story how the lord of the domain originally chose a proper situation for his mansion on high ground; but, strange to say, what the earthly workmen reared during each day was sure to be taken down again by visionary hands in the night-time, till at length a voice was heard commanding him to build iii the low ground-a command which he duly obeyed. A three-topped hill is sure to have been split by diabolical power. A solitary rocky isle is a stone dropped from her apron by some migrating witch. Nay, we find that, a wear having been thrown across the Tweed at an early period for the driving of mills, the common people, when its origin was forgotten, came to view it as one of certain pieces of taskwork which Michael Scott the wizard imposed upon his attendant imps, to keep them from employing their powers of torment upon himself. Flat rock surfaces and solitary slabs of stone very often present hollows, oblong or round, resembling the impressions which would be made upon a soft surface by the feet of men and animals. The real origin of such hollows we now know to be the former presence of concretions of various kinds which have in time been worn out. But in every part of the earth we find that these apparent footprints have given rise to legends, generally involving supernatural incidents. Thus a print about two feet long, on the top of the lofty hill called Adam's Peak, in Ceylon, is believed by the people of that island to be the stamp of Buddha's foot as he ascended to heaven; and, accordingly, it is amongst them an object of worship. Even simpler objects of a natural kind have become the bases of myths. Scott tells us, in Marmion, how, in popular conception, St Cuthbert sits and toils to frame The sea-born beads that bear his name; said beads being in fact sections of the stalks of encrinites, stone-skeletoned animals allied to the star-fish, which flourished in the early ages of the world. Their abundance on the shore of Holy Island, where St Cuthbert spent his holy life in the seventh century, is the reason why his name was connected with their supposed manufacture. The so-called fairy-rings in old pastures-little circles of a brighter green, within which, it is supposed, the fairies dance by night-are now known to result from the outspreading propagation of a particular agaric, or mushroom, bywhich the ground is manured for a richer following vegetation. At St. Catherine's, near Edinburgh, is a spring containing petroleum, an oil exuding from the coal-beds below, but little understood before our own age. For many centuries this mineral oil was in repute as a remedy for cutaneous diseases, and the spring bore the pretty name of the Balm Well. It was unavoidable that anything so mysterious and so beneficial should become the subject of a myth. Boece accordingly relates with all gravity how St Catherine was commissioned by Margaret, the consort of Malcolm Canmore, to bring her a quantity of holy oil from Mount Sinai. In passing over Lothian, by some accident she happened to lose a few drops of the oil; and, on her earnest supplication, a well appeared at the spot, bearing a constant supply of the precious unguent. Sound science interferes sadly with. these fanciful old legends, but not always without leaving some doubtful explanation of her own. The presence of water-laid sand and gravel in many parts of the earth very naturally suggests tales of disastrous inundations. The geologist him-self has heretofore been accustomed to account for such facts by the little more rational surmise of a discharged lake, although there might be not the slightest trace of any dam by which it was formerly held in. The highland fable which described the parallel roads of Glenroy as having been formed for the use of the hero Fingal, in hunting, was condemned by the geologist: but the lacustrine theory of Macculloch, Lauder, and other early speculators, regarding these extraordinary natural objects, is but a degree less absurd in the eyes of those who are now permitted to speculate on upheavals of the frame of the land out of the sea-a theory, however, which very probably will sustain great modifications as we become better acquainted with the laws of nature, and attain more clear insight into their workings in the old world before us. QUARANTINEIf a hundred persons were asked the meaning of the word quarantine, it is highly probable that ninety-nine would answer, 'Oh! it is something connected with shipping the plague and yellow-fever.' Few are aware that it simply signifies a period of forty days; the word, though common enough at one time, being now only known to us through the acts for preventing the introduction of foreign diseases, directing that persons coming from infected places must remain forty days on shipboard before they be permitted to land. The old military and monastic writers frequently used the word to denote this space of time. In a trace between Henry the First of England and Robert Earl of Flanders, one of the articles is to the following effect:-'If Earl Robert should depart from the treaty, and the parties could not be reconciled to the king in three quarantines, each of the hostages should pay the sum of 100 marks.' From a very early period, the founders of our legal polity in England, when they had occasion to limit a short period of time for any particular purpose, evinced a marked predilection for the quarantine. Thus, by the laws of Ethelbert, who died in 616, the limitation for the payment of the fine for slaying a man at an open grave was fixed to forty nights, the Saxons reckoning by nights instead of days. The privilege of sanctuary was also confined within the same number of days. The eighth chapter of Magna Charta declares that 'A widow shall remain in her husband's capital messuage for forty days after his death, within which time her dower shall be assigned.' The tenant of a knight's fee, by military service, was bound to attend the king for forty days, properly equipped for war. According to Blackstone, no man was in the olden time allowed to abide in England more than forty days, unless he were enrolled in some tithing or decennary. And the same authority asserts that, by privilege of Parliament, members of the House of Commons are protected from arrest for forty days after every prorogation, and forty days before the next appointed meeting. By the ancient Costumale of Preston, about the reign of Henry II, a condition was imposed on every new-made burgess, that if he neglected to build a house within forty days, he should forfeit forty pence. In ancient prognostications of weather, the period of forty days plays a considerable part. An old Scotch proverb states: Saint Swithin's day, gin ye do rain, For forty days it will remain; Saint Swithin's day, and ye be fair, For forty days 'twill rain nae mair. There can be no reasonable doubt that this precise term is deduced from the period of Lent, which is in itself a commemoration of the forty days' fast of Christ in the wilderness. The period of forty days is, we need scarcely say, of frequent occurrence in Scripture. Moses was forty days on the mount; the diluvial rain fell upon the earth for forty days; and the same period elapsed from the time the tops of the mountains were seen till Noah opened the window of the ark. Even the pagans observed the same space of time in the mysteries of Ceres and Proserpine, in which the wooden image of a virgin was lamented over during forty days; and Tertullian relates as a fact, well known to the heathens, that for forty days an entire city remained suspended in the air over Jerusalem, as a certain presage of the Millennium. The process of embalming used by the ancient Egyptians lasted forty days; the ancient physicians ascribed many strange changes to the same period; so, also, did the vain seekers after the philosopher's stone and the elixir of life. |