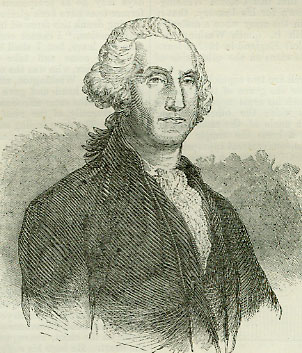

22nd FebruaryBorn: Dr. Richard Price, statist, 1723, Tynton; George Washington, President of the United States, 1731, Bridge's Creek, Virginia; Charles Duke of Richmond, 1735; Rev. Gilbert Wakefield, classical scholar, 1756, Nottingham. Died: David II (of Scotland), 1371, Edinburgh Castle; Frederick I (of Tuscany), 1609: Frederick Ruysch, anatomist, 1639, The Hague: James Barry, painter, 1806, Marylebone; Smithson Tennant, chemist, 1815, Boulogne; Dr. Adam Ferguson, historian, 1816, St. Andrew's; Rev. Sydney Smith, wit and littérateur, 1845, St. George's, Hanover-square. Feast Day: Saints Thalasius and Limneus, 5th century. St. Baradat, 5th century. St. Margaret, of Cortona, 1297. GEORGE WASHINGTON

'George Washington, without the genius of Julius Caesar or Napoleon Bonaparte, has a far purer fame, as his ambition was of a higher and holier nature. Instead of seeking to raise his own name, or seize supreme power, he devoted his whole talents, military and civil, to the establishment of the independence and the perpetuity of the liberties of his own country. In modern history no man has done such great things with-out the soil of selfishness or the stain of a groveling ambition. Cæsar, Cromwell, Napoleon attained a higher elevation, but the love of dominion was the spur that drove them on. John Hampden, William Russell, Algernon Sydney, may have had motives as pure, and an ambition as sustained; but they fell. To George Washington alone in modern times has it been given to accomplish a wonderful revolution, and yet to remain to all future times the theme of a people's gratitude, and an example of virtuous and beneficent power.' The pre-eminence here accorded to Washington will meet with universal approval. He clearly and unchallengeably stands out as the purest great man in universal history. While America feels a just pride in having given him birth, it is something for England to know that his ancestors lived for generations upon her soil. His great-grandfather emigrated about 1657, having previously lived in Northamptonshire. The Washingtons were a family of some account. Their history has been traced by the Rev. J. N. Simpkinson, rector of Brington, near Northampton, with tolerable clearness, in a volume entitled The Washingtons, published in 1860, but more concisely in a speech which he delivered at a meeting of American citizens in London, on Washington's birthday, two years later: 'The Washingtons,' he says, 'were a Northern family, who lived some time in Durham, and also in Lancashire. It was from Lancashire that they came to Northamptonshire. It is a pleasure to me to be able to point out what induced them to come to Northamptonshire. The uncle of the first Lawrence Washington was Sir Thomas Kitson, one of the great merchants who, in the time of Henry VII and Henry VIII, developed the wool trade of the country. That wool trade depended mainly on the growth of wool, and the creation of sheep farms in the midland counties. I have no doubt, therefore, that the reason why Lawrence Washington settled in Northamptonshire, leaving his own profession, which was that of a barrister, was that he might superintend his uncle's transactions with the sheep-proprietors in that county. Lawrence Washington soon became Mayor of Northampton, and at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries, being identified with the cause of civil and religious liberty, he gained a grant of some monastic lands. Sulgrave was granted to him. It will be interesting to point out the connexion which existed between him and my parish of Brington. In that parish is situated Althorp, the seat of the Spencers. The Lady Spencer of that day was herself a Kitson, daughter of Washington's uncle, and the Spencers were great promoters of the sheep-farming movement. Thus, then, there was a very plain connexion between the Washingtons and the Spencers. The rector of the parish at that time was Dr. Layton, who was Lord Cromwell's prime commissioner for the dissolution of monasteries. Therefore we see another cause why the lands of Sulgrave were granted to Lawrence Washington. For three generations they remained at Sulgrave, taking rank among the nobility and gentry of the county. At the end of three generations their fortunes failed. They were obliged to sell Sulgrave, and they then retired to our parish of Brington, being, as it were, under the wing of the Spencer family. . . From this depression the Washingtons recovered by a singular marriage. The eldest son of the family had married the half-sister of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, which at this time was not an alliance above the pretensions of the Washingtons. They rose again into great prosperity. About the emigrant I am not able to discover much: except that he, above all others of the family, continued to be on intimate terms with the Spencers down to the very eve of the civil war; that he was knighted by James I in 1623; and that we possess in our county not only the tomb of his father, but that of the wife of his youth, who lies buried at Islip-on-the-Nen. When the civil war broke out, the Washingtons took the side of the King. ... You all know the name of Sir Henry Washington, who led the storming arty at Bristol, and defended Worcester. 'We have it, on the contemporary authority of Lloyd, that this Colonel Washing-ton was so well known for his bravery, that it became a proverb in the army when a difficulty arose: 'Away with. it, quoth Washington.' The emigrant who left England in 1657, I leave to be traced by historians on the other side of the Atlantic.' In Brington Church are two sepulchral stones, one dated 1616 over the grave of the father of the emigrant, in which his arms appear impaled with those of his wife; the other covering the remains of the uncle of the same person, and presenting on a brass the simple family shield, with the extraneous crescent appropriate to a younger brother. Of the latter a transcript is here given, that the reader maybe enabled to exercise a judgment in the question which has been raised as to the origin of the American flag. It is supposed that the stars and stripes which figure in that national blazon were taken from the shield of the illustrious general, as a compliment no more than due to him. In favour of this idea it is to be remarked that the stripes of the Washingtons are alternate gules and white, as are those of the national flag; the stars in chief, moreover, have the parallel peculiarity of being five-pointed, six points being more common. The scene at the parting of Washington with his officers at the conclusion of the war of Independence, is feelingly described by Mr. Irving: 'In the course of a few days Washington prepared to depart for Annapolis, where Congress was assembling, with the intention of asking leave to resign his command. A barge was in waiting about noon on the 4th of December at 'Whitehall ferry, to convey him across the Hudson to Paulus Hook. The principal officers of the army assembled at Fraunces' tavern in the neighbourhood of the ferry, to take a final leave of him. On entering the room, and finding him-self surrounded by his old companions in arms, who had shared with him so many scenes of hardship, difficulty, and danger, his agitated feelings overcame his usual self-command. Filling a glass of wine, and turning upon them his benignant but saddened countenance, 'With a heart full of love and gratitude,' said he, 'I now take leave of you, most devoutly wishing that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honourable.' Having drunk this farewell benediction, he added with emotion, 'I cannot come to each of you to take my leave, but I shall be obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.' General Knox, who was the nearest, was the first to advance. Washington, affected even to tears, grasped his hand and gave him a brother's embrace. In the same affectionate manner he took leave severally of the rest. Not a word was spoken. The deep feeling and manly tenderness of these veterans in the parting moment could not find utterance in words. Silent and solemn they followed their loved commander as he left the room, passed through a corps of light infantry, and proceeded on foot to Whitehall ferry. Having entered the barge, he turned to them, took off his hat, and waved a silent adieu. They replied in the same manner, and having watched the barge until the intervening point of the battery shut it from sight, returned still solemn and silent to the place where they had assembled.' THE REV. SYDNEY SMITH

The witty canon of St. Paul's (he did not like to be so termed) expired on the 22nd of February 1845, in his seventy-fourth year, at his house, No. 56, Green-street, Grosvenor-square. He died of water on the chest, consequent upon disease of the heart. He bore his sufferings with calmness and resignation. The last person he saw was his brother Bobus, who survived him but a few days, -literally fulfilling the petition in a letter written by Sydney two-and-thirty years before, 'to take care of himself, and wait for him.' He acids: 'We shall both be a brown infragrant powder in thirty or forty years. Let us contrive to last out for the same time, or nearly the same time.' His daughter, Lady Holland, thus touchingly relates an incident of his last days: My father died in peace with himself and with all the world; anxious to the last to pro-mote the comfort and happiness of others. He sent messages of kindness and forgiveness to the few he thought had injured him. Almost his last act was bestowing a small living of £120 per annum on a poor, worthy, and friendless clergyman, who had lived a long life of struggle with poverty on £40 per annum. Full of happiness and gratitude, he entreated he might be allowed to see my father; but the latter so dreaded any agitation, that he most unwillingly consented, saying, Then he must not thank me; I am too weak to bear it.' He entered-my father gave him a few words of advice-the clergyman silently pressed his hand, and blessed his death-bed. Surely, such blessings are not given in vain.' Of all the estimates which have been written of the genius and character of the Rev. Sydney Smith, none exceeds in truthful illustration that which Earl Russell has given in the Memoirs, &c., of Thomas Moore: 'His (Sydney Smith's) great delight was to produce a succession of ludicrous images: these followed each other with a rapidity that scarcely left time to laugh; he himself laughing louder, and with more enjoyment than any one. This electric contact of mirth came and went with the occasion; it cannot be repeated or reproduced. Anything would give occasion to it. For instance, having seen in the newspapers that Sir Æneas Mackintosh was conic to town, he drew such a ludicrous caricature of Sir Æneas and Lady Dido, for the amusement of their namesake, that Sir James Mackintosh rolled on the floor in fits of laughter, and Sydney Smith, striding across him, exclaimed 'Ruat Justitia.' His powers of fun were, at the same time, united with the strongest and most practical common sense. So that, while he laughed away seriousness at one minute, he destroyed in the next some rooted prejudice which had braved for a thousand years the battle of reason and the breeze of ridicule. The Letters of Peter Plylnlel bear the greatest likeness to his conversation; the description of Mr. Isaac Hawkins Brown dancing at the court of Naples, in a volcano coat, with lava buttons, and the comparison of Mr. Canning to a large blue-bottle fly, with its parasites, most resemble the pictures he raised up in social conversation. It may be averred for certain, that in this style he has never been equalled, and I do not suppose he will ever be surpassed.' 'Sydney,' says Moore, 'is, in his way, inimitable; and as a conversational wit, beats all the men I have ever met. Curran's fancy went much higher, but also much lower. Sydney, in his gayest flights, though boisterous, is never vulgar.' It was for the first time learned, from his daughter's book, in what poverty Sydney Smith spent many years of his life, first in London, afterwards at a Yorkshire parsonage. It was not, however, that painful kind of poverty which struggles to keep up appearances. He wholly repudiated appearances, confessed poverty, and only strove, by self-denial, frugality, and every active and economic device, to secure as much comfort for his family as could be legitimately theirs. In perfect conformity with this conduct, was that most amusing anecdote of his preparations to receive a great lady-paper lanterns on the evergreens, and a couple of jack-asses with antlers tied on to represent deer in the adjacent paddock. He delighted thus to mock aristocratic pretensions. The writer has heard (he believes) an inedited anecdote of him, with regard to an over-flourishing family announce in a newspaper, which would have made him out to be a man of high grade in society. 'We are not great people at all,' said he, 'we are common honest people-. people that pay our bills.' In the like spirit was his answer to a proposing county historian, who inquired for the Smythe arms-'The Smythes never had any arms, but have always sealed their letters with their thumbs.' Even when a little gleam of prosperity enabled him at last to think that his family wanted a carriage, observe the philosophy of his procedure: 'After diligent search, I discovered in the back settlements of a York coachmaker an ancient green chariot, sup-posed to have been the earliest invention of the kind. I brought it home in triumph to my ad-miring family. Being somewhat dilapidated, the village tailor lined it, the village blacksmith repaired it; nay, (but for Mrs. Sydney's earnest entreaties,) we believe the village painter would have exercised his genius upon the exterior; it escaped this danger, however, and the result was wonderful. Each year added to its charms, it grew younger and younger; a new wheel, a new spring; I christened it the ' Immortal;' it was known all over the neighbourhood; the village boys cheered it, and the village dogs barked at it; but 'Faber niece fortunce ' was my motto, and we had no false shame.' FRENCH DESCENT IN WALESThis day is memorable as being that on which, in the year 1797, the last invasion by an enemy was made on the shores of the island of Great Britain. At ten o'clock in the morning, three ships of war and a lugger were seen to pass 'the Bishops '-a group of rocks off St. David's Head in Pembrokeshire. The ships sailed under English colours; but the gentleman by whom they were discovered had been a sailor in his youth, and readily recognised them as French men-of-war with troops on board. He at once despatched one of his domestics to alarm the inhabitants of St. David's, while he himself watched the enemy's motions along the coast towards Fishguard. At this latter town the fort was about to fire a salute to the British flag, when the English colours were struck on board the fleet, and the French ensign hoisted instead. Then the true character of the ships was known, and the utmost alarm prevailed. Messengers were despatched in all directions to give notice of a hostile invasion; the numbers of the enemy were fearfully exaggerated; vehicles of all kinds were employed in transporting articles of value into the interior. The inhabitants of St. David's mustered in considerable numbers; the lead of the cathedral roof was distributed to six blacksmiths and cast into bullets; all the powder to be obtained was divided amongst those who possessed firearms; and then the whole body marched to meet the enemy. On the 23rd, several thousand persons, armed with muskets, swords, pistols, straightened scythes on poles, and almost every description of offensive weapon that could be obtained, had assembled. The enemy, meanwhile, whose force consisted of 600 regular troops and 800 convicts and sweepings of the French prisons, had effected a landing unopposed at Pencaer, near Fishguard. About noon on the following day the ships that had brought them sailed unexpectedly, and thus the troops were cut off from all means of retreat. Towards evening all the British forces that could be collected, consisting of the Castlemartin yeomanry cavalry, the Cardiganshire militia, two companies of fencihle infantry, and some seamen and artillery, under the command of Lord Cawdor, arrived on the scene, and formed in battle array on the road near Fishguard. Shortly afterwards, how-ever, two officers were sent by the French commander (Tate) with an offer to surrender, on the condition that they should be sent back to Brest by the British Government. The British commander replied that an immediate and unconditional surrender was the only terms he should allow, and that unless the enemy capitulated by two o'clock, and delivered up their arms, he would attack them with 10,000 men. The 10,000 men existed, for available purposes, only in the speech of the worthy commander; but the French general did not seem disposed to be very inquisitive, and the capitulation was then signed. On the morning of the 25th the enemy accordingly laid down their arms, and were marched under escort to various prisons at Pembroke, Haverfordwest, Milford, and Carmarthen. Five hundred were confined in one jail at Pembroke; of these one hundred succeeded in making their escape through a subterranean passage, 180 feet long, which they had dug in the earth at a depth of three feet below the surface. Many wonderful stories are told in reference to this invasion. What follows is related in Tales and Traditions of Tenby: 'A tall, stout, masculine-looking female, named Jemima Nicholas, took a pitchfork, and boldly marched towards Pencaer to meet the foe; as she approached, she saw twelve Frenchmen in a field; she at once advanced towards them, and either by dint of her courage, or rhetoric, she had the good fortune to conduct them to, and confine them in, the guard-house at Fishguard.' . . 'It is asserted that Merddin the prophet foretold that, when the French should land here, they would drink of the waters of Finon Crib, and would cut down a hazel or nut tree that grew on the side of Finon Well, along with a white-thorn. The French drank of that water, and cut down the trees as prophesied. We must also give our readers an account of Enoch Lake's dream and vision. About thirty years before the French invasion, this man lived near the spot where they landed. One night, he dreamed that the French were landing on Carreg Gwasted Point; he told his wife, and the impression was so strong, that he arose, and went to see what was going on, when he distinctly saw the French troops land, and heard their brass drums. This he told his wife and many others, who would not believe him till it had really happened.' FAMILIAR NAMESIn the hearty familiarity of old English manners, it was customary to call all intimates and friends by the popular abbreviations of their Christian names. It may be, therefore, considered as a proof at once of the popularity of poets and the love of poetry, that every one who gained any celebrity was almost invariably called Tons, Dick, Harry, &c. Heywood in his curious work, the Hierarchie of Blessed Angels, complains of this as an indignity to the worshippers of the Muse. Our modern poets to that end are driven, Those names are curtailed which they first had given, And, as we wished to have their memories drowned, We scarcely can afford them half their sound. Greene, who had in both academies ta'en Degree of Master, yet could never gain To be called more than Robin; who, had he Profest aught but the muse, served and been free After a seven years' prenticeship, might have, With credit too, gone Robert to his grave. Marlowe, renowned for his rare art and wit, Could ne'er attain beyond the name of Kit; Although his Hero and Leander did Merit addition rather. Famous Kid 'Was called but Tom. Tom Watson, though he wrote Able to make Apollo's self to dote Upon his muse, for all that he could strive, Yet never could to his full name arrive. Tom Nash, in his time of no small esteem, Could not a second syllable redeem; Excellent Beaumont, in the foremost rank Of th' rarest wits, was never more than Frank. Mellifluous Shakespeare, whose enchanting quill Commanded mirth or passion, was but Will. And famous Jonson, though his learned pen Be dipt in Castaly, is still but Ben. Fletcher and Webster, of that learned pack None of the mean'st, yet neither was but Jack. Decker's hut Tom, nor May, nor Middleton, And here's now but Jack Ford that once was John. Soon after, however, he takes the proper view of the subject, and attributes the custom to its right cause. I, for my part, Think others what they please, accept that heart That courts my love in most familiar phrase: And that it takes not from my pains or praise, If any one to me so bluntly come: I hold he loves me best that calls me Tom.' |