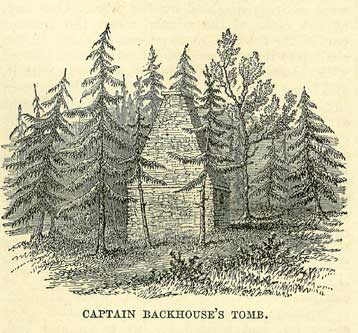

21st JuneBorn: Anthony Collins, author of a Philosophical Enquiry into Liberty and Necessity, &c., 1676, Heston, near Hounslow, Middlesex. Died: Thales, Grecian philosopher, B.C. 546, Olympia; Edward III of England, 1377, Shene, Richmond; John Skelton, poet, 1529; Captain John Smith, colonizer of Virginia, 1631; Sir Inigo Jones, architect, 1651; William Beckford, Lord Mayor of London, 1770; John Armstrong, poet, 1797, London; Gilbert, first Earl of Minto, statesman, 1814; Mrs. Mary Anne Clarke (n'ee Farquhar), 1852. Feast Day: St. Eusebius, Bishop of Samosata, and martyr, 379 or 380; St. Aaron, Abbot in Brittany, 6th centnry; St. Meen, Mevenus, or Melanus, Abbot in Brittany, about 617; St. Leufredus, or Leufroi, abbot, 738; St. Ralph, Archbishop of Bourges, confessor, 866; St. Aloysius, or Lewis Gonzaga, confessor, 1591. SKELTONSkelton was poet laureate in the reign of Henry the Eighth. He had been at one time Henry's tutor, and was honoured with some appointment at the date of that monarch's accession, as a small token of royal favour. But neither his influence nor his merits seem to have procured him any other advancement in the church than the curacy of Trumpington, a village near Cambridge, and a living in Norfolk. He indulged a vein much too satirical to please those to whom his satire had reference, and probably made himself many enemies. 'A pleasant conceited fellow, and of a very sharp wit; exceeding bold, and could nip to the very quick when he once set hold.' Skelton lived in the first dawn of that revival in poetry which brightened into a clear noon in the reign of Queen Bess; his verse is the veriest gingle imaginable. The reader will be curious to examine a specimen of the poetry of one whom so great a scholar as Erasmus called 'the glory and light of British literature.' One of the laureate's most fanciful effusions is a poem on a dead sparrow, named Philip, of whom Gib, the cat, had got hold. Perhaps the following is the most presentable extract we can make: Alas! my heart it stings, Remembering pretty things; Alas! mine heart it sleeth My Philip's doleful death. When I remember it, How prettily it would sit; Many times and oft, Upon my finger aloft, I played with him, tittle-tattle, And fed him with my spattle, With his bill between my lips, It was my pretty Phips. Many a pretty kusse Had I off his sweet musse. And now the cause is thus, That he is slain me fro, To my great pain and woe. But Skelton's favourite theme was abuses in the church. This is the title of one of his indiscriminate satirical attacks: Here after foloweth a litle boke called Colyn Clout, compiled by Master Skelton, Poet Laureate. As a clue to what is coming, the author is pleased to prefix a Latin motto: 'Who will rise up with me against the evil-doers, or who will defend my cause against the workers of iniquity? No man, Lord.' Skelton begins at once to cut at what he considers the root of the evil;-to wit, the bishops. He tells us what strange reports of their doings have reached him: Men say indede How they take no hede Their sely shepe to fede, Bat plucke away and pul The fleces of their wall. He hears how: They gaspe and they gape, Al to have promocion; and then he draws an inference which must have been harrowing to a bishop's conscience: Whiles the heades doe this, The remnaunt is amis Of the clergy all, Both great and small. Skelton is willing to make all possible excuses for their lordships; he allows, indeed, the report of 'the temporality ' to be well founded, that: bishoppes disdain Sermons for to make, Or such labour to take; But he says this is not to be ascribed in every case to sloth, for that some of them have actually no alternative: They have but small art, And right sclender cunnyng Within their heades wunning. Then he proceeds to deal at some length with the minor orders. He dwells on sundry personal vices, to which those more insignificant offenders were commonly addicted, but reserves his severest satire for their vile ignorance. They know nothing, he says: they catch a 'Dominus Vobiscum by the head,' and make it serve all religious ends. And yet such men will presume to the office of teacher: Take they cnres of soules And woketh never what they redo, Pater noster nor crede; and as to their construing: Construe not worth a whistle Nether Gospel nor Pistle. We must really join with the poet in his philosophic deduction from this survey: A priest without a letter, Without his virtue be greater, Doutlesse were much better Upon him for to take A mattoeke or a rake. It was not to be expected that so virulent a truth-teller would escape the net of the wicked. It happened that Skelton-not being allowed, as a priest, to marry-had thought himself justified in evading what he considered an unfair rule by simply overlooking the ceremony. For this ingenious proceeding, Nix, Bishop of Norwich, took occasion to suspend him. But worse was to come. Having presumed to attack Wolsey in the very height of his power, that proud prelate was fain to procure a writ of arrest; and so honest Skelton had to take sanctuary at Westminster, and remained there till his death. One of Skelton's poems is a long one in his usual incoherent style, entitled The Tunning of Eleanour Bumming, referring to an alewife so called, who dwelt: In a certain stead Beside Leatherhead; where he says: She breweth noppy ale, And maketh thereof fast sale To travellers, to tinkers, To sweaters, to swinkers, And all good ale-drinkers. She was, he assures us, one of the most frightful of her sex, being: ------ ugly of cheer, Her face all bowsy, Wondrously wrinkled; Her een bleared, And she gray-haired. Her kirtle Bristow-red, With cloths upon her head That weigh a sow of lead. And when the reader surveys the annexed portrait of Eleanour, borrowed from the frontispiece of one of the original editions of the poem, he will probably acknowledge that Skelton did her no injustice. When Skelton wore the laurel crown, My ale put all the alewives down.  Mr. Dalloway, one of Skelton's editors, speculates on the possibility of the poet having made acquaintance with the Leatherhead alewife while residing with his royal master at Nonsuch Palace, eight miles off; and he alleges that the domicile near the bridge still exists. This must be considered as requiring authentication. It appears, however, that there existed about the middle of the last century an alehouse on the road from Cambridge to Hardwicke, which bore a swinging sign, on which there could alone be discerned a couple of handled beer mugs, exactly in the relative situation of the two pots in the hands of Eleanour Mumming, as represented in her portrait. It looks as if it were a copy of that portrait, from which all had been obliterated but the pots: or, if this surmise could not be received, there must have been some general characteristic involved in such an arrangement of two ale-pots on a sign or portrait. The gentleman who communicated a sketch of the sign and its couple of pots to the Gentleman's Magazine for May 1794, recalled the Thepas Amphikupellon of Vulcan, adverted to by Homer, and as to which learned commentators were divided-some asserting it was a cup with two handles, while others believed it to be a cup internally divided. The sign of the Two-pot House--for so it was called-had convinced him that 'the Grecian poet designed to introduce neither a bi-ansated nor a bi-cellular pot, but a pot for each hand: and consequently that a brace of pots, instead of a single one, were the legitimate object of his description.' HENRY HUDSON, THE NAVIGATORThis ill-fated mariner was one of the most remarkable of our great English navigators of Elizabethan age, yet his history previous to the year 1607, when he sailed on his first recorded voyage, is entirely unknown. The Dutch appear to have invented, in order to support their claim to New Netherlands, a history of his previous life, according to which he had passed a part of it in the service of Holland; but this is not believed by the best modern writers on the subject. We first find Henry Hudson, in the year just mentioned, a captain in the service of the Muscovy Company, whose trade was carried on principally with the North, and who did not yet despair of increasing it by the discovery of a passage to China by the north-east or by the north-west. Hudson laboured with a rare energy to prove the truth or fallacy of their hopes, and he was at least successful in showing that some of them were delusive: and he would no doubt have done much more, had he not been cut off in the midst of his career. He acted first on a plan which had been proposed by an English navigator, named Robert Thorne, as early as the year 1527-that of sailing right across the north pole: and he left London for this voyage on the 23rd of April 1607. Among his companions was his son, John Hudson, who is described in the log-book as 'a boy,' and who seems to have accompanied his father in all his expeditions. He sailed by way of Greenland towards Spitzbergen, and in his progress met with the now well-known ice-barrier between those localities, and he was the first modern navigator who sailed along it. He eventually reached the coast of Spitzbergen, but after many efforts to overcome the difficulties which presented themselves in his way, he was obliged to abandon the hope of reaching the pole; and, after convincing himself that that route was impracticable, he returned home, and on the 15th of September arrived at Tilbury, in the Thames. On the 22nd of April in the following year (1608) Hudson, still in the employment of the Muscovy Company, sailed from London with the design of ascertaining the possibility of reaching China by the north-east, and, as we may now suppose, was again unsuccessful: he reached Gravesend on his return on the 26th of August. After his return from this voyage, Hudson was invited to Holland by the Dutch East India Company, and it was in their service that he made his third voyage. Sailing from Amsterdam on the 6th of April 1609, with two ships, manned partly by Dutch and partly by English sailors, he on the 5th of May reached the North Cape. It was originally intended to renew the search for a north-east passage, but in consequence of a mutiny amongst his crew when near Nova Zembla, he abandoned this plan, and sailed west-ward to seek a passage through America in lat. 40°. He had received vague information of the existence of the great inland lakes, and imagined that they might indicate a passage by sea through the mainland of America. It was on this voyage that he discovered the great river which has since borne his name: but his hopes were again disappointed, and he returned to England, and arrived at Dartmouth, in Devonshire, on the 7th of November. Hudson was detained in England by orders of the government, on what grounds is not known, while the ship returned to Holland. The indefatigable navigator had now formed a design of seeking a passage by what has been named after him, Hudson's Straits: and on the 17th of April 1610 he started from London with this object, in a ship named the Discovery. During the period between the middle of July and the first days of August he passed through Hudson's Straits, and on the 4th of the latter month he entered the great bay which, from the name of its discoverer, has ever since been called Hudson's Bay. The months of August, September, and October were spent in exploring the southern coast of this bay, until, at the beginning of November, Hudson took up his winter quarters in what is supposed to have been the south-east corner of James's Bay, and the ship was soon frozen in. Hudson did not leave these winter quarters until the 18th of June following, and his departure was followed by the melancholy events which we have now to relate. We have no reason for believing that Hudson was a harsh-tempered man: but his crew appears to have been composed partly of men of wild and desperate characters, who could only be kept in order by very severe discipline. Before leaving the Thames, he had felt it necessary to send away a man named Colburne, who appears to have been appointed as his second in command, probably because this man had shewn an inclination to dispute his plans and to disobey his orders: and while wandering about the southern coasts of Hudson's Bay, signs of insubordination had manifested themselves on more than one occasion, and had required all Hudson's energy to suppress them. The master's mate, Robert Juet, and the boatswain seem to have distinguished themselves by their opposition on these occasions: and shortly before they entered winter quarters they were deprived of their offices. But, as we learn from the rather full account left by Abacuk Prickett, one of the survivors of this voyage, the principal leader of the discontented was an individual who had experienced great personal kindnesses from Henry Hudson. This was a young man named Henry Green, of a respectable family of Kent, but who had been abandoned by his relatives for his extravagance and ill-conduct; during Hudson's last residence in London, Green seems to have been literally living on his charity. Finding that this Green could write well, and believing that he would be otherwise useful, Hudson took him out with him on his voyage as a sort of supernumerary, for he was not entered on the books of the company who sent out the ship, and had therefore no wages: but Hudson gave him provisions and lodgings in the ship as his personal attendant. In the beginning of the voyage Green quarrelled with several of the crew, and made himself otherwise disagreeable: but the favour of the captain (or master) saved him from the consequences, and he seems to have gradually gained the respect of the sailors for his reckless bravery. While the ship was locked up in the ice for the winter, the carpenter greatly provoked Hudson by refusing to obey his orders to build a timber hut on shore: and next day, when the carpenter chose to go on shore to shoot wild fowl, as it had been ordered that nobody should go away from the ship alone, Green, who had been industriously exciting the men against their captain, went with him. Hudson, who had perhaps received some intimation of his treacherous behaviour, was angry at his acting in this contemptuous manner, and shewed his displeasure in a way which embittered Green's resentment. Under these circumstances, it was not difficult to excite discontent among the men, for it seems to have been the first time that any of them had passed a winter in the ice, and they were not very patient under its rigour, for some of them were entirely disabled by the frost. One day, at the close of the winter, when the greater part of the crew were to go out a-fishing in the shallop (a large two-masted boat), Green plotted with others to seize the shallop, sail away with it, and leave the captain and a few disabled men in the ship: but this plot was defeated by a different arrangement made accidentally by Hudson. The conspiracy against the latter was now ripe, and Prickett, who was evidently more consenting to it than he is willing to acknowledge, tells us that when night approached, on the eve of the 21st of June, Green and Wilson, the new boat-swain, came to him where he lay lame in his cabin, and told him 'that they and the rest and their associates would shift the company and turne the master and all the sicke men into the shallop, and let them shift for themselves.' The conspirators were up all night, while Hudson, apparently quite unconscious of what was going on, had retired to his cabin and bed. Probably he was in the habit of fastening his door; at all events, they waited till he rose in the morning, and as he left his cabin at an early hour, three of the men seized him from behind and pinioned him: and when he asked what they meant, they told him he should know when he was in the shallop. They then took all the sick and lame men out of their beds, and these, with the carpenter and one or two others who at the last remained faithful to their captain-not forgetting the boy John Hudson-were forced into the shallop. Then, as Prickett tells us, 'they stood out of the ice, the shallop being fast to the sterne of the shippe, and so (when they were nigh out, for I cannot say they were cleane out) they cut her head fast from the sterne of our shippe, then out with their topsails, and towards the east they [the mutineers] stood in a cleare sea.' This was the last that was ever seen or heard of Henry Hudson and his companions in misfortune. Most of them cripples, in consequence of the severity of the winter, without provisions, or means of procuring them, they must soon have perished in this inhospitable climate. The fate of the mutineers was not much. better. For some time they wandered among coasts with which they were unacquainted, ran short of provisions, and failed in their attempts to gain a sufficient supply by fishing or shooting; and for some time seem to have lived upon little more than 'cockle-grass.' At first they seem to have proceeded without any rule or order: but finally Henry Green was allowed to assume the office of master or captain, and they were not decided as to the country in which they would finally seek a refuge, for they thought 'that England was no safe place for them, and Henry Greene swore the shippe should not come into any place (but keep the sea still) till he had the king's majestie's hand and seal to shew for his safetie.' What prospect Green had of obtaining a pardon, especially while he kept out at sea, is altogether unknown: but he was not destined to survive long the effects of his treachery. On the 28th of July the mutineers came to the mouth of Hudson's Straits, and landed at the promontory which he had named Digges's Cape, in search of fowl. They there met with some of the natives, who showed so friendly a disposition, that Green-contrary, it seems, to the opinion of his companions-landed next day without arms to hold further intercourse with them. But the Indians, perceiving that they were unarmed, suddenly attacked them, and in the first onset Green was killed, and the others with great difficulty got off their boat and reached the ship, where Green's three companions, who were all distinguished by their activity in the mutiny, died of their wounds. Prickett, sorely wounded, and another man, alone escaped. Thus four of the most able hands were lost, and those who remained were hardly sufficient to conduct the ship. For some time they were driven about almost helpless, but they succeeded in killing a good quantity of fowl, which restored their courage. But when the fowls were eaten, they were again driven to great extremities. 'Now went our candles to wracke, and Bennet, our cooke, made a messe of meate of the bones of the fowle, frying them with candle-grease till they were crispe, and, with vinegar put to them, made a good dish of meate. Our vinegar was shared, and to every man a pound of candles delivered for a weeke, as a great daintie.' At this time Robert Juet, who had encouraged them by the assurance that they would soon be on the coast of Ireland, died of absolute starvation. 'So our men cared not which end went forward, insomuch as our master was driven to looke to their labour as well as his owne: for some of them would sit and see the fore sayle or mayne sayle flie up to the tops, the sheets being either flowne or broken, and would not helpe it themselves nor call to others for helpe, which much grieved the master.' At last they arrived on the Irish coast, but were received with distrust, and with difficulty obtained the means to proceed to Plymouth, from whence they sailed round to the Thames, and so to London. Prickett was a retainer of Sir Dudley Digges, one of the subscribers to the enterprise, through whom probably they hoped to escape punishment; but they are said to have been immediately thrown into prison, though. what further proceedings were taken against them is unknown. Next year a captain named Batton was sent out in search of Hudson and his companions, and passed the winter of 1612 in Hudson's Bay, but returned without having obtained any intelligence of them. Thus perished this great but ill-fated navigator. Yet the name of the apparently obscure Englishman, of whose personal history we know so little, has survived not only in one of the most important rivers of the new continent, in the Strait through which he passed, and in the bay in which he wintered and perished, but in the vast extent of territory which lies between this bay and the Pacific Ocean, and which has so long been under the influence of the Hudson's Bay Company; and the results of his voyages have been still more remarkable, for, as it has been well observed, he not only bequeathed to his native country the fur-trade of the territory last mentioned, and the whale-fisheries of Spitzbergcn, but he gave to the Dutch that North American colony which, having afterwards fallen into the hands of England, developed itself into the United States. SEPULCHRAL VAGARIESAlthough it has been the general practice of our country, ever since the Norman era, to bury the dead in churchyards or other regular cemeteries, yet many irregular and peculiar burials have taken place in every generation. A few examples may be useful and interesting. They will serve to illustrate human eccentricity, and go far to account for the frequent discovery of human remains in mysterious or unexpected situations. Many irregular interments are merely the result of the caprices of the persons there buried. Perhaps there is nothing that more forcibly shews the innate eccentricity of a man than the whims and oddities which he displays about his burial. He will not permit even death to terminate his eccentricity. His very grave is made to commemorate it, for the amusement or pity of future generations. These sepulchral vagaries, however, vary considerably both in character and degree. Some are whimsical and fantastical in the extreme: others, apparently, consist only in shunning the usual and appointed places of interment; while the peculiarity of others appears, not in the place, but in the mode of burial. We will now exemplify these remarks. From a small Hertfordshire village, named Flaunden, there runs a lonely footpath across the fields to another village. Just at the most dreary part of this road, the stranger is startled by suddenly coining upon a modern-looking altar tomb, standing close by the path. It is built of bricks, is about two feet and a half high, and covered with a large stone slab, bearing this inscription: SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF MR. WILLIAM LIBERTY, OF CHORLEY WOOD, BRICKMAKER, WHO WAS BY HIS OWN DESIRE BURIED IN A VAULT IN THIS PART OF HIS ESTATE. HE DIED 21 APRIL 1777, AGED 53 YEARS. HERE ALSO LIETH THE BODY OF MRS ALICE LIBERTY. WIDOW OF THE ABOVE-NAMED WILLIAM LIBERTY, SHE DIED 29 MAY 1809, AGED 82 YEARS. There is nothing peculiar about the tomb. It is just such a one as may be seen in any cemetery. But why was it placed here? Was it to commemorate Mr. Liberty's independence of sepulchral rites and usages? or to inform posterity that this ground once was his own? or was it to scare the simple rustic as he passes by in the shades of evening? Certain it is that: The lated peasant dreads the dell, For superstition 's wont to tell Of many a grisly sound and sight, Scaring its path at dead of night.  About a mile from Great Missenden, a large Buckinghamshire village, stands a queer-looking building-a sort of dwarf pyramid, which is locally called 'Captain Backhouse's tomb.' It is built of flints, strengthened with bricks: is about eleven feet square at the base: the walls up to about four or five feet are perpendicular: then they taper pyramidieally, but instead of terminating in a point, a flat slab-stone about three feet square forms the summit. There is a small gothic window in the north wall, and another in the south: the western and part of the southern walls are covered with ivy. (See the accompanying illustration.) This singular tomb stands in a thick wood or plantation, on a lofty eminence, about a quarter of a mile from Havenfield Lodge, the house in which Mr. Backhouse resided. He had been a major or captain in the East Indian service, but quitting his military life, he purchased this estate, on which he built himself a house of one story, in Eastern fashion, and employed himself in planting and improving his property. He is described as a tall, athlete man, of a stern and eccentric charaeter. As he advanced in life his eccentricity increased, and one of his eccentric acts was the erection of his own sepulchre within his own grounds, and under his own superintendence. 'I'll have nothing to do,' said he, 'with the church or the churchyard! Bury me there, in my own wood on the hill, and my sword with me, and I'll defy all the evil spirits in existence to injure me!' He died, at the age of eighty, on the 21st of June 1800, and was buried, or rather deposited, according to his own directions, in the queer sepulchral he himself had erected. His sword was placed in the coffin with him, and the Coffin reared upright within a niche or recess in the western wall, which was then built up in front, so that he was in fact immured. It is said in the village that he was never married, but had two or three illegitimate sons, one of whom became a Lieutenant-General. This gentleman, returning from India about seven years after his father's death, had his father's body removed to the parish churchyard, placing over his grave a large handsome slab, with a suitable inscription: and this fact is recorded in the parish register: August 8th, 1807.-The remains of Thomas Backhouse, Esq., removed, by a faculty from the Arch-deacon of Buckingham, from the mausoleum in Havenfield to the ehurchyard of Great Missenden, and there interred. This removal has given rise to a popular notion in the village that Mr. Backhouse was buried on his estate, 'to keep possession of it till his son returned. For, don't you see,' say these village oracles, 'that when his son came back from abroad, and took possession of the property, he had his father's corpse taken from the queer tomb in Havenfieid Wood, and decently buried in the churchyard?' This 'queer tomb' has occasioned some amusing adventures, one of which was the following. As some boys were birds'-nesting in Havenfieid Wood, they came up to this tomb, and began to talk about the dead man that was buried there, and that it was still haunted by his ghost; when one boy said to another, 'Jack, I'll lay you a penny you dursn't put your head into that window, and shout out, Old Backhouse!' 'Done!' said Jack. They struck hands, and the wager was laid. Jack boldly threw down his cap, and thrust his head in through the window, and ealled aloud, 'Old ----' His first word roused an owl within from a comfortable slumber; and she, bewildered with terror, rushed to the same window, her usual place of exit, to escape from this unwonted intrusion. Jack, still more terrified than the owl, gave his head a sudden jerk up, and stuck it fast in the narrow part of the window. Believing the owl to be the dead man's ghost, his terror was beyond conception. He struggled, he kicked, he shrieked vociferously. With this hubbub the owl became more and more terrified. She rushed about within-flapping her wings, hooting, screeching, and every moment threatening frightful onslaughts on poor Jack's head. The rest of the boys, imagining Jack was held fast by some horrid hobgoblin, rushed away in consternation, screaming and bellowing at the full pitch of their voices. Fortunately, their screams drew to them some workmen from a neighbouring field, who, on hearing the cause of the alarm, hastened to poor Jack's assistance. He had liberated himself from his thraldom, but was lying panting and unconscious on the ground. He was carried home, and for some days it was feared his intellect was impaired: but after a few weeks he perfectly recovered, though he never again put his head into Captain Backhouse's tomb, and his adventure has become safely enrolled among the traditions of Missenden. Sir William Temple, Bark, a distinguished statesman and author, who died at his seat of Moor Park, near Farnham, in 1700, ordered his heart to be enclosed in a silver box, or china basin, and buried under 'a sun-dial in his garden, over against a window from whence he used to contemplate and admire the works of God, after he had retired from worldly business.' Sir James Tillie, knight, who died in 1712, at his seat of Pentilly Castle, in Cornwall, was buried by his own desire under a tower or summer-house which stood in a favourite part of his park, and in which he had passed many joyous hours with his friends. A baronet, of some military fame, who died in a midland county in 1823, directed in his will that after his death his body should be opened by a medical man, and afterwards covered with a sere-cloth, or other such perishable material, and thus interred, without a coffin, in a particular spot in his park: and that over his grave should be sown a quantity of acorns, from which the most promising plant being selected, it should be there preserved and carefully cultured, 'that after my death my body may not be entirely useless, but may serve to rear a good English oak.' He left a small legacy to his gardener, ' to see that the plant is well watered, and kept free from weeds.' The directions of the testator were fully complied with, except that the interment, instead of being in the prescribed spot, took place in the churchyard adjoining the mansion. The oak over the grave is now a fine healthy tree. Baskerville, the famous printer, who died in 1775, is said to have been buried by his own desire under a windmill near his garden. Samuel Johnson, an eccentric dancing-master in Cheshire, who died in 1773, aged eighty-two, was, by his own request from the owner, buried in a plantation forming part of the pleasure-grounds of the Old Hall at Gawsworth, near Macclesfield: and a stone stating the circumstances still stands over his grave. A farmer named Trigg, of Stevenage, Hells, directed his body to be enclosed in lead, and deposited in the tie-beam of the roof of a building which was once his barn: and where it may still be seen. The coffin enclosing the body of another eccentric character rests on a table in the summer-house belonging to a family residence in Northamptonshire. Mr. Hull, a bencher of the Inner Temple, who died in 1772, was buried beneath Leith Hill Tower, in Surrey, which he had himself erected a few years before his death. Thomas Hollis, a gentleman of considerable property, resided for some years before his death on his estate at Corscomb, in Dorset. He was very benevolent, an extreme Liberal, and no less eccentric. In his will, which was in other respects remarkable, he ordered his body to be buried ten feet deep in any one of certain fields of his lying near his house: and that the whole field should immediately afterwards he ploughed over, that no trace of his burial-place might remain. It is remarkable that, while giving directions to a workman in one of these very fields, he suddenly fell down, and almost instantly expired, on the 1st of January 1774, in the fifty-fourth year of his age, when he was buried according to his directions. It is the popular opinion that these irregular burials are the result of infidelity. But this opinion must be received with great caution, for in most instances it might be proved to be erroneous. Mr. Hollis, for example, was a large benefactor to both Church and Dissent. He attended the public worship of both: nearly rebuilt, at his own cost, the parish church at Corscomb: and the last words he uttered were, 'Lord have mercy upon me! Receive my soul!' Instances of persons desiring to be buried in some favourite spot are too numerous to be specified. A few examples only will suffice to illustrate this peculiarity. Mr. Booth, of Brush House, Yorkshire, desired to be buried in his shrubbery, became he himself had planted it, and passed some of his happiest hours about it. Doctor Renny, a physician at Newport Pagnel, Bucks, for a similar reason was buried in his garden, on a raised plot of ground, surrounded by a sunk fence. In the same county, near a village named Radnage, Thomas Withers, an opulent German, who died January 1st, 1843, aged sixty-three, was by his own direction buried 'beneath the shade of his own trees, and in his own ground.' But one of the most interesting burials of this description is on the Chiltern Hills, in the same county. It is called The Shepherd's Grave, and though in the parish of Aston Clinton, is yet far away from the village and the habitations of man; it is in a lonely spot on the Chilterns, that remarkable range of hills which crosses Buckinghamshire, and stretches on the one side into Berks, and oil the other into Bedfordshire. High on a towering knoll, it commands a fine panoramic view of the whole surrounding country. To this spot, about a century ago, a shepherd named Faithful was wont to lead his flock day by day, to depasture on the heathery turf around. Here, from morning to night, was his usual resting-place. Here he sat to eat his rustic meals. Here he rested to watch his sheep, as, widely spread before and around him, they diligently nibbled the scanty herbage of these chalky downs. Here, without losing sight of his flock, he could survey a vast expanse of earth and heaven-could contemplate the scenes of nature, and admire many a celebrated work of man. Here, as he sat at perfect ease, his eye could travel into six counties-a hundred churches came within the compass of his glance-mansions and cottages, towns and villages in abundance lay beneath his feet. And he was not a man whose mind slept while his eyes be-held the wonders of nature or of art: he became a wise and a learned, though unlettered philosopher. His head was silvered o'er with age, And long experience made him sage: In summer's heat and winter's cold He fed his flock and penned his fold: His wisdom and his honest fame Through all the country raised his name. The spot which had been from youth to age the scene of his labours, his meditations, and enjoyments, had become so endeared to him, that he wished it to become his last earthly resting-place. 'When my spirit has fled to those glorious scenes above,' said he to his fellow-shepherds, 'then lay my body here.' He died, and there they buried him. And let no one say it was to him unconsecrated ground. It had been hallowed by his strict attention to duties: by meditations which had refined and elevated his mind: by heavenly aspirations, and spiritual communion with Him who is the only true sanctifier of all that is holy. His neighbours cut in the turf over his grave this rude epitaph: Faithful lived, and Faithful died, Faithful lies buried on the hill side: The hill so wide the fields surround, In the day of judgment he'll be found. Up to a recent period the shepherds and rustics of the neighbourhood were accustomed 'to scour' the letters: and as they were very large, and the soil chalky, the words were visible at a great distance. The 'scouring' having been discontinued, the word 'Faithful' alone could he discerned in 1848, but the grave is still held in reverence, and generally approached with solemnity by the rustics of the neighbourhood. A burial, which turned out to be remarkable in its results, took place on the moors near Hope, in Derbyshire. In the year 1674 a farmer and his female servant, in crossing these moors on their way to Ireland, were lost in the snow, with which they continued covered from January to May. Their bodies on being found were in such an offensive state that the coroner ordered them to be buried on the spot. Twenty-nine years after their burial, for some reason or other now unknown, their graves were opened, and their bodies were found to be in as perfect a state as those of persons just dead. The skin had a fair and natural colour, and the flesh was soft and pliant: and the joints moved freely, without the least stiffness. In 1716, forty-two years after the accident, they were again examined in the presence of the clergyman of Hope, and were found still in the same state of preservation. Even such portions of dress as had been left on them had undergone no very considerable change. Their graves were about three feet deep, and in a moist and mossy soil. The antiseptic qualities of moss are well known. Many ancient burials were curious, as the following instances exemplify. Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, though the founder of the rich Abbey of Walden, and in other ways a liberal benefactor to the Church, was excommunicated for taking possession of the, Abbey of Ramsey and converting it into a fortress, which he did in a case of extremity, to save himself from the sword of his pursuers. While under this sentence of excommunication, he was mortally wounded in the head by an arrow from the bow of a common soldier. 'He made light of the wound,' says an ancient writer, 'but he died of it in a few days, under excommunication. See here the just judgment of God, memorable through all ages! While that abbey was converted into a fortress, blood exuded from the walls of the church and the cloister adjoining, witnessing the Divine indignation, and prognosticating the destruction of the impious. This was seen by many persons, and I observed it with my own eyes.' Having died while under sentence of excommunication, the earl, notwithstanding his liberal benefactions to the Church, was inadmissible to Christian burial. But just before he breathed his last some Knights-Templars visited him, and finding him very penitent, from a sense of compassion, or of gratitude for bounties received from him, they threw over him 'the habit of their order, marked with a red cross,' and as soon as he expired, 'carried his dead body into their orchard at the Old Temple in London: and coffining it in lead, hanged it on a crooked tree.' Some time afterwards, 'by the industry and expenses' of the Prior of Walden, absolution for the earl was obtained from Pope Alexander III; and now his dead body, which had been hung like a scarecrow on the branch of a tree, became so precious that the Templars and the Prior of Walden contended for the honour of burying it. The Templars, however, triumphed by burying it privately or secretly in the porch before the west door of the New Temple. So that his body,' continues Dngdale, 'was received amongst Christians, and divine offices celebrated for him.' Howel Sele was buried in the hollow trunk of a tree, which from him received the name of 'Howells Oak.' Owen Glendour, his cousin, but feudal adversary, having killed him in single combat, Madoc, a friend and companion of Owen, in order to hide the dead body from Howel's vassals who were searching for him, thrust it into a hollow tree. The circumstance is thus given in the popular ballad, in the words of Madoc: I marked a broad and blasted oak, Scorched by the lightning's livid glare; Hollow its stem from branch to root, And all its shrivelled arms were bare. Be this, I cried, his proper grave (The thought in me was deadly sin); Aloft we raised the helpless chief, And dropped his bleeding corpse within. The tree is still pointed out to strangers as 'Howel's Oak,' or, 'The spirit's blasted tree.' And to this day the peasant still, With cautious fear, avoids the ground: In each wild branch a spectre sees, And trembles at each rising sound. We sometimes meet with a peculiar kind of ancient burial, which is chiefly interesting from the amusing legends connected with it. This is where the stone coffin, which contains the remains of the deceased, is placed within an external recess in the wall of a church, or under a low arch passing completely through the wall, so that the coffin, being in the middle of the wall, is seen equally within and without the church. At Brent Pelham, Herts, there is a monument of this description in the north wall of the nave. It is supposed to commemorate 0' Piers Shonkes, lord of a manor in the parish. The local tradition is, that by killing a certain serpent he so exasperated the spiritual dragon, that he declared he would have the body of Shonkes when he died, whether he was buried within or without the church. To avoid such a calamity, Shonkes ordered his body to be placed in the wall, so as to be neither inside nor outside the church. This tomb, says Chauncey, had formerly the following inscription over it: Tantum fama manet, Cadmi Sanctiq. Georgi Posthuma, Tempus edax ossa, sepulchra vorat: Hoc tamen in muro tutus, qui perdidit anguem, Invito, positus, Demonie Shonkus Brat. Nothing of Cadmus nor St. George, those names Of great renown, survives them but their fames: Time was so sharp set as to make no bones Of theirs, nor of their monumental stones. But Shonkes one serpent kills, t'other defies, And in this wall as in a fortress lies. In the north wall of the church of Tremeirchion, North Wales, there is a tomb which is said to commemorate a necromancer priest, who died vicar of the parish about 1340. The tradition here is that this priestly wizard made a compact with the 'Prince of Magicians,' that if he would permit him to practise the black art with impunity during his life, he should possess his body at his death, whether he was buried in or out of the church. The wily priest out-witted his subtle master, by ordering his body to be buried neither inside nor outside of the church, but in the middle of its wall. There are so many similar tombs, with similar legends connected with them, that one cannot but wonder the master of subtilty should have been so often outwitted by the same manoeuvre. The dreadful punishment of immuring persons, or burying them alive in the walls of convents, was undoubtedly sometimes resorted to by monastic communities. Skeletons thus built up in cells or niches have frequently been found in the ruins of monasteries and nunneries. A skeleton thus immured was discovered in the convent of Penwortham, Lancashire: and Sir Walter Scott, who mentions a similar discovery in the ruins of Coldingham Abbey, thus describes the process of immuring: A small niche, sufficient to inclose the body, was made in the massive wall of the convent: a slender pittance of food and water was deposited in it, and the awful words, FADE IN PACEM, were the signal for immuring the criminal. On this awful species of punishment Sir Walter Scott has founded one of the striking episodes in his poem of Marmion. We can only give a short extract. Two criminals are to be immured-a beautiful nun who had fled after her lover, and a sordid wretch whom she had employed to poison her rival. They are now in a secret crypt or vault under the convent, awaiting the awful sentence. Yet well the luckless wretch might shriek, Well might her paleness terror speak! For there were seen, in that dark wall, Two niches,-narrow, deep, and tall: Who enters at such griesly door, Shall ne'er, I ween, find exit more. And now that blind old abbot rose, To speak the chapter's doom On those the wall was to inclose Alive, within the tomb, But stopped, because that woeful maid, Gathering her powers, to speak essayed. After revealing the cause of her flight, she is very effectively described as concluding with these prophetic words: Yet dread me from my living tomb, Ye vassal slaves of bloody Rome! Behind a darker hour ascends! The altars quake, the crosier bends: The ire of a despotic king Rides forth upon destruction's wing. Then shall these vaults, so strong and deep, Burst open to the sea-winds' sweep: Some traveller then shall find my bones, Whitening amid disjointed stones, And, ignorant of priests' cruelty, Marvel such relics here should be. We have also instances on record of persons being buried alive in the earth. Leland, in his account of Brackley, in Northamptonshire, says: In the churcheyarde lyethe an image of a priest revested (divested), the whiche was Vicar of Brakeley, and there buried quike by the tyranny of a Lord of the Towne, for a displeasure that he tooke with hym for an horse taken, as some say, for a mortuarie. But the Lord, as it is there sayde, went to Rome for absolution, and toke greate repentauns. In Notes and Queries, vol. vi. p. 245, we are informed that, in the parish of Ensbury, Dorset, there is a tradition that on a spot called Patty Barn a man was many years ago buried alive up to the neck, and a guard set over him to prevent his being removed or fed by friends, so that he was left to die in this wretehed state from starvation. Another instance of this kind of burial, with which we will conclude, is connected with a curious family legend. Sir Robert de Shurland, Lord of Shurland, in the Isle of Sheppy, Kent, was attached to a lady who unhappily died unanointed and unaneled, and consequently the priest refused to bury her with the rites of sepulture. Sir Robert, roused to madness by the indignity, ordered his vassals to bury the priest alive. Perhaps he did not expect to be obeyed. But his obsequious vassals instantly executed his command to the letter. Hereupon the impetuous knight, having somewhat cooled, became alarmed: and fearing the consequences of his sacrilegious murder, mounted his favourite charger, swam across the arm of the sea which separated Sheppy from the main land, galloped to court, and obtained the king's pardon for a crime which he had, he said, unwittingly committed in a fit of grief and indignation. 'He made the church a present, by the way,' to atone for his crime; but the prior of a neighbouring convent predicted that the gallant steed which had now saved his life would hereafter be the cause of his death. Like a prudent man, he ordered the poor horse to be stabbed, and thrown into the sea with a stone tied round his neck: and, in self-gratulation, assumed the motto, 'Fato prudentia major' (Prudence is superior to fate). Twenty years afterwards the aged knight was hobbling on the sands, in all the 'dignity of gout,' when he saw a horse's skeleton with a stone fastened round the neck. Giving it a kick, 'Ah!' he exclaimed, 'this must be my poor old horse.' The sharp points of the vertebree pierced through his velvet shoe, and inflicted a wound in his toe which ended in mortification and death: thus fulfilling the predietion. The tomb of Sir Robert Shurland is still to be seen in Minster Church, under a Gothic arch in the south wall. The effigy is cross-legged, and on the right side is sculptured a horse's head emerging from the waves of the sea, as if in the act of swimming. The vane of the tower of the church represented in Grose's time a horse's head, and the church was called `The Horse Church.' John Wilkinson, the great iron founder, having made his fortune by the manufacture of iron, determined that his body should be encased by his favourite metal when he died. In his will he directed that he should be buried in his garden, in an iron coffin, with an iron monument over him of twenty tons weight; and he was so buried within thirty yards of his mansion of Castlehead. He had the coffin made long before his death, and used to take pleasure in showing it to his visitors, very much to the horror of many of them. He would also make a present of an iron coffin to any one who might desire to possess one. When he came to be placed in his narrow bed, it was found that the coffin he had provided was too small, so he was temporarily interred until another could. be made. When placed in the ground a second time, the coffin was found to be too near the surface; accordingly it was taken up, and an excavation cut in the rock, after which it was buried a third time. On the Castlehead estates being sold in 1828, the family directed the coffin again to be taken up, and removed to the neighbouring chapel-yard of Lindale, where it now lies. A man is still living (1802) at the latter place, who assisted at all the four interments. |