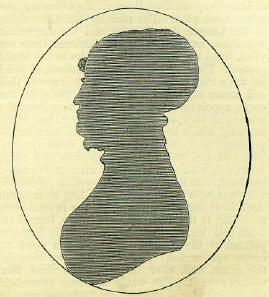

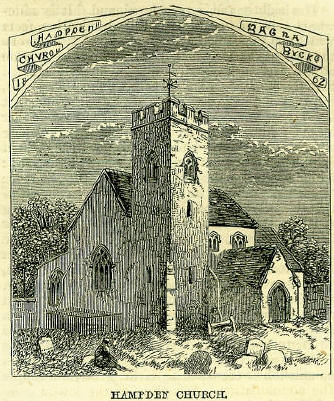

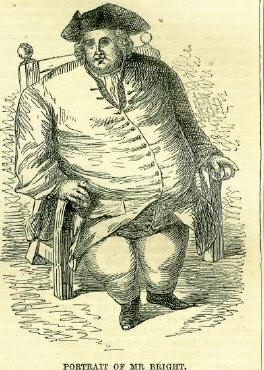

21st JulyBorn: Matthew Prior, English poet, 1664, Winborne, Dorsetslzire. Died: Darius III, king of Persia, murdered by Bessus, 330 B.C.; Pope Nicholas II, 1061; William Lord Russell, beheaded in Lincoln's-Inn-Fields, 1683; James Butler, Duke of Ormond, 1688; Daniel Sennertus, learned physician, 1637, Wittenberg; Robert Burns, national poet of Scotland, 1796, Dumfries; Peter Thelusson, celebrated millionaire, 1797, Plastow, Essex. Feast Day: St. Praxedes, virgin, 2nd century. St. Zoticus, bishop and martyr, about 204. St. Victor of Marseilles, martyr, beginning of 4th century. St. Barhadbeschiahas, deacon and martyr, 354. St. Arbogast', bishop of Strasburg, confessor, about 678. THE DEATH AND FUNERAL OF BURNS, FROM THE NEWSPAPERS OF THE TIMEOn the 21st [July, 1796] died, at Dumfries, after a lingering illness, the celebrated Robert Burns. His poetical compositions, distinguished equally by the force of native humour, by the warmth and tenderness of passion, and by the glowing touches of a descriptive pencil, will remain a lasting monument of the vigour and the versatility of a mind guided only by the lights of nature and the inspiration of genius. The public, to whose amusement he has so largely contributed, will learn with regret that his extraordinary endowments were accompanied with frailties which rendered hint useless to himself and family. The last months of his short life were spent in sickness and indigence, and his widow, with five infant children, and the hourly expectation of a sixth, is now left without any resource but what she may hope from the regard due to the memory of her husband.' A subscription for the widow and children of poor Burns is immediately to be set on foot, and there is little doubt of its being an ample one.  Actuated by the regard which is due to the shade of such a genius, his remains were interred on Monday last; the 25th July, with military honours and every suitable respect. The corpse having been previously conveyed to the town-hall of Dumfries, remained there till the following ceremony took place: The military there, consisting of the Cinque Port Cavalry, and the Angusshire Fencibles, having handsomely tendered their services, lined the streets on both sides to the burial-ground. The Royal Dumfries Volunteers, of which he was a member-in uniform, with crape on their left arms, supported the bier; a party of that corps, appointed to perform the military obsequies, moving in slow, solemn time to the 'Dead March in Saul,' which was played by the military band-preceded in mournful array with arms reversed. The principal part of the inhabitants and neighbourhood, with a number of particular friends of the bard, from remote parts, followed in procession; the great bells of the churches tolling at intervals. Arrived at the churchyard gate, the funeral-party, according to the rules of that exercise, formed two lines, and leaned their heads on their firelocks, pointed to the ground. Through this space the corpse was carried. The party drew up alongside the grave, and, after the interment, fired three volleys over it. The whole ceremony presented a solemn, grand, and affecting spectacle, and accorded with the general regret for the loss of a man whose like we shall scarce see again. EPITAPH Consigned to earth, here rests the lifeless clay, Which once a vital spark from Heaven inspired; The lamp of genius shone full bright as day, Then left the world to mourn its light retired. While beams that splendid orb which lights the spheres While mountain streams descend to swell the main-- While changeful seasons mark the rolling years- Thy fame, 0 Burns, let Scotia still retain! To these interesting notices may here be fitly appended, what, apart from intrinsic merit, may be considered the most remarkable production ever penned regarding Burns. It was at the centenary of his birth, January 25, 1859, that a great festival was held at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, in honour of the memory of the Scottish national poet. Many personal relics of the illustrious dead were shewn; there was a concert of his best songs. Then it was announced to the vast and highly-strung auditory, that the offered prize of fifty guineas had brought together 621 poems by different authors, in honour of Burns's memory; out of which the three gentlemen judges had selected one as the best; and this was forthwith read by Mr. Phelps, the eminent tragedian, with thrilling effect. It proved to be the composition of a young countrywoman of Burns, up to that time scarcely known, but who was in some respects not less wonderful, as an example of genius springing up in the lowly paths of life-her name, ISA CRAIG. There was an enthusiastic call for the youthful prize-holder, and had she been present, she would have received honours exceeding in fervour those at the laureation of Petrarch; but Miss Craig was then pursuing her modest duties in a distant part of London, unthinking of the proceedings at Sydenham. The poem was as follows: We hail this morn, A century's noblest birth; A Poet peasant-born, Who more of Fame's immortal dower Unto his country brings, Than all her Kings! As lamps high set Upon some earthly eminence And to the gazer brighter thence Than the sphere-lights they flout- Dwindle in distance and die out, While no star waneth yet; So through the past's far-reaching night Only the star-souls keep their light. A gentle boy With moods of sadness and of mirth, Quick tears and sudden joy- Grew up beside the peasant's hearth. His father's toil he shares; But half his mother's cares From his dark searching oyes, Too swift to sympathise, Hid in her heart she bears. At early morn, His father calls him to the field; Through the stiff soil that clogs his feet, Chill rain and harvest heat, He plods all day; returns at eve outworn, To the rude fare a peasant's lot doth yield; To what else was he born? The God-made King Of every living thing (For his great heart in love could hold them all; The dumb eyes meeting his by hearth and stall- Gifted to understand! Knew it and sought his hand; And the most timorous creature had not fled, Could she his heart have read, Which fain all feeble things had bless'd and sheltered. To Nature's feast Who knew her noblest guest And entertain'd him best Kingly he came. Her chambers of the east She drap'd with crimson and with gold, And pour'd her pure joy-wines For him the poet-soul'd. For him her anthem roll'd From the storm-wind among the winter pines, Down to the slenderest note Of a love-warble, from the linnet's throat. But when begins The array for battle, and the trumpet blows, A King must leave the feast, and lead the fight. And with its mortal foes Grim gathering hosts of sorrows and of sins- Each human soul must close. And Fame her trumpet blew Before him; wrapp'd him in her purple state; And made him mark for all the shafts of fate, That henceforth round him flew. Though he may yield Hard-press'd, and wounded fall Forsaken on the field; His regal vestments soil'd His crown of half its jewels spoil'd; He is a king for all. Had he but stood aloof! Had he array'd himself in armour-proof Against temptation's darts! So yearn the good; so those the world calls wise, With vain presumptuous hearts, Triumphant moralise. Of martyr-woe A sacred shadow on his memory rests; Tears have not ceas'd to flow; Indignant grief yet stirs impetuous breasts, To think-above that noble soul brought low, That wise and soaring spirit, fool'd, enslav'd Thus, thus he had been saved! It might not be That heart of harmony Had been too rudely rent; Its silver chords, which any hand could wound, By no hand could be tun'd, Save by the Maker of the instrument, Its every string who knew, And from profaning touch his heavenly gift withdrew. Regretful love His country fain would grove, By grateful honours lavish'd on his grave; Would fain redeem her blame That he so little at her hands can claim, Who unrewarded gave To her his life-bought gift of song and fame. The land he trod Hath now become a place of pilgrimage; Where dearer are the daisies of the sod That could his song engage. The hoary hawthorn, wreath'd Above the bank on which his limbs he flung While some sweet plaint he breath'd; The streams he wander'd near; The maidens whom he lov'd; the songs he sung; All, all are dear! The arch blue eyes- Arch but for love's disguise Of Scotland's daughters, soften at his strain; Her hardy sons, sent forth across the main To drive the ploughshare through earth's virgin soils, Lighten with it their toils; And sister-lands have learn'd to love the tongue In which such songs are sung. For doth not Song To the whole world belong! Is it not given wherever tears can fall, Wherever hearts can melt, or blushes glow, Or mirth and sadness mingle as they flow, A heritage to all?  The widow of Burns survived him a time equal to his own entire life-thirty-eight years-and died in the same room in which he had died, in their humble home at Dumfries, in March 1834. The celebrity he gave her as his 'bonnie Jean,' rendered her an object of much local interest; and it is pleasant to record, that her conduct throughout her long widowhood was marked by so much good sense, good principle, and general amiableness and worth, as to secure for her the entire esteem of society. One is naturally curious about the personality of a poet's goddess; and much silent criticism had Mrs. Burns accordingly to endure. A sense of being the subject of so much curiosity made her shrink from having any portraiture of herself taken; but one day she was induced, out of curiosity regarding silhouettes, to go to the studio of a wandering artist in that style, and sit to him. The result is here represented. The reader will probably have to regret the absence of regularity in the mould of the features; yet the writer can assure him that, even at the age of fifty-eight, Jean was a sightly and agreeable woman. It is understood that, in her youth, while decidedly comely, her greatest attractions were those of a handsome figure-a charm which came out strongly when engaged in her favourite amusement of dancing. PETER THELUSSONPeter Thelusson was born in France, of a Genevese family, and as a London merchant trading in Philpot Lane, he acquired an enormous fortune. He died on the 21st of July 1797, and when his will was opened, its provisions excited in the public mind mingled wonder, indignation, and alarm. To his dear wife, Ann, and children he left £100,000; and the residue of his property, amounting to upwards of £600,000, he committed to trustees, to accumulate during the lives of his three sons, and the lives of their sons, and when sons and grandsons were all dead, then the entire property was to be transferred to his eldest great-grandson. Should no heir exist, the accumulated property was to be conveyed to the sinking fund for the reduction of the national debt. Various calculations were made as to the probable result of the accumulation. According to the lowest computation, it was reckoned that, at the end of seventy years, it would amount to £19,000,000. Some estimated the result at far higher figures, and saw, in the fulfilment of the bequest, nothing short of a national disaster. The will was generally stigmatised as unwise or absurd, and, moreover, illegal. The Thelusson family resolved to test its legality, and raised the question in Chancery. Lord Chancellor Loughborough, in 1799, pronounced the will valid, and on appeal to the House of Lords, his decision was unanimously affirmed. The will, though within the letter of the law, was certainly adverse to its spirit, which 'abhors perpetuities,' and an act was passed by parliament in 1800, rendering null all bequests for the purposes of accumulation for longer than twenty years after the testator's death. Thelusson's last grandson died in 1856. A dispute then arose whether Thelusson's eldest great-grandson, or the grandson of Thelusson's eldest son, should inherit. The House of Lords decided, on appeal in 1859, that Charles S. Thelusson, the grandson of Thelusson's eldest son, was the heir. It is said that, instead of about a score of millions, by reason of legal expenses and accidents of management, little more than the original sum of £600,000 fell to his lot. HAMPDEN'S BURIAL AND DISINTERMENTThe parish church of Great Hampden, the burial-place of the Hampden family, is situated in the south-eastern part of Buckinghamshire, three miles from Great Missenden, through which passes the turnpike-road from Aylesbury to London. It is a pretty village church, with a flamboyant window at the west end, and other interesting features; and, standing embosomed in trees, in a secluded but elevated position, has a strikingly picturesque and pleasing appearance. The chancel contains many memorials of the Hampden family, whose bodies lie interred beneath. Here also was buried John Hampden, commonly called 'the Patriot.'  On Sunday morning, June 18, 1643, while encamped at Wallington, in Oxfordshire, he received intelligence that Prince Rupert, with a large body of troopers, had been ravaging, during the night, the neighbourhood of Chinnor and Wycombe, and was returning to Oxford, laden with spoil, and carrying off two hundred prisoners. Hampden, without waiting for his own regiment of infantry, placed himself at the head of a body of troopers, and galloped off with all speed in pursuit of the plunderers. On arriving at Chalgrove, instead of finding, as he expected, a retreating enemy, he beheld them drawn up in order of battle in the open field, waiting his approach. An encounter ensued, and, in the first onset, Hampden was severely wounded. Finding himself powerless, and seeing his troops in disorder and consternation, he left the battlefield. While the bells of his peaceful little church were chiming for morning-worship, Hampden was riding, in agonies of pain, to Thame, where he placed himself under surgical care. On the following Sunday, a large company of soldiers, chiefly Hampden's 'green coats,' entered the park-gates which opened into that noble avenue of beeches, nearly a mile in extent, which still forms the magnificent approach to Hampden House, and its adjoining church. With their drums and banners muffled, with their arms reversed and their heads uncovered, those soldiers moved slowly up the avenue, chanting the 90th Psalm, and carrying with them the dead body of their lamented colonel. The bell tolled solemnly as they approached, and crowds of mourners were assembled to receive the melancholy cortege. Hampden was much beloved, especially in his own county, and by his own tenantry and dependants. The weather-beaten faces of many sturdy yeomen were that day bedewed with tears. 'Never,' says Clough, 'were heard such piteous cries at the death of one man as at Master Hampden's.' 'His death,' says Clarendon, 'was as great a consternation to his party as if their whole army had been defeated, or cut off.' A grave was dug for him near his first wife's, in the chancel of the little church, where from childhood he had been wont to worship. And there, in the forty-ninth year of his age, was buried. 'John Hampden, the patriot,' June 25, 1643.  Nearly two centuries later, on July 21, 1828, Hampden's death was the occasion of a more extraordinary scene in this church, owing to the actual cause of it having been differently stated. Clarendon, and other contemporary writers, attributed it to the effects of two musket-balls received in his shoulder from the fire of his adversaries; whereas Sir Robert Pye, who married. Hampden's daughter, asserted that his death was caused by the bursting of his own pistol, which so shattered his hand, that he died from the effects of the wound. To decide which of these statements was correct, Lord Nugent, who was about to write the biography of Hampden, obtained permission to examine his body, and for this purpose a large party, on the day above named, assembled in Hampden church, among whom were Lord Nugent; Counsellor, afterwards Lord Denman; the rector of the parish; Mr. Heron, the Earl of Buckinghamshire's agent; Mr. George Coventry, and 'six other young gentlemen; twelve grave-diggers and assistants, a plumber, and the parish clerk.' The work began at an early hour in the morning, by turning up the floor of the church. The dates and initials on several leaden coffins were examined; but on coming to the coffin supposed to be Hampden's, the plate was found 'so corroded that it crumbled and fell into small pieces on being touched,' which rendered the inscription illegible. But from this coffin lying near the feet of Hampden's first wife, to whom he had himself erected a memorial, it was concluded to be his; and 'it was unanimously agreed that the lid should be cut open, to ascertain the fact.' The plumber descended 'and commenced cutting across the coffin, then longitudinally, until the whole was sufficiently loosened to roll back the lead, in order to lift off the wooden lid beneath, which came off nearly entire. Beneath this was another wooden lid, which was also raised without being much broken. The coffin was filled up with saw-dust, 'which was removed, and the process of examination commenced. Silence reigned. Not a whisper or a breath was heard. Each stood on the tiptoe of expectation, awaiting the result. Lord Nugent descended into the grave, and first removed the outer cloth, which was firmly wrapped round the body, then the second, and a third. Here a very singular scene presented itself. No regular features were apparent, although the face retained a deathlike whiteness, and shewed the various windings of the blood-vessels beneath the skin. The upper row of teeth was perfect, and those that remained in the under-jaw, on being taken out and examined, were found quite sound. A little beard remained on the lower part of the chin; and the whiskers were strong, and somewhat lighter than his hair, which was a full auburn brown.' The coffin was now raised from the grave, and placed on a trestle in the centre of the church. The arms, which 'nearly retained their original size, and presented a very muscular appearance,' were examined. The right arm was without its hand, which had apparently been amputated. On searching under the clothes, the hand, or rather a number of small bones enclosed in a separate cloth, was found, but no finger-nails were discovered, although on the left hand they remained almost perfect. The resurrectionists 'were now perfectly satisfied' that Hampden's hand had been shattered by the bursting of his pistol. Still it was possible that he might have been wounded at the same time in the shoulder by a musket-ball from the enemy; and to corroborate or disprove this statement, a closer examination was made. 'It was adjudged necessary to remove the arms, which were amputated with a penknife.' The result was, that the right arm was found properly connected with the shoulder, but the left, being 'loose and disunited from the scapula, proved that dislocation had taken place' 'In order to examine the head and hair, the body was raised up and supported with a shovel.' 'We found the hair in a complete state of preservation. It was a dark auburn colour, and, according to the custom of the times, was very long, from five to six inches. It was drawn up, and tied round at the top of the head with black thread or silk. On taking hold of the top-knot, it soon gave way, and came off like a wig.' 'He was five feet nine inches in height, apparently of great muscular strength, of a vigorous and robust frame, forehead broad and high, the skull altogether well formed-such an one as the imagination would conceive capable of great exploits.' The body was duly re-interred, and shortly afterwards a full description of the examination, from which the foregoing has been abridged, appeared in the Gentleman's Magazine, when, to the discomposure of the party concerned, it was confidently asserted that the disinterred body was not John Hampden's, but that of a lady who died durance partu, and that the bones, mistaken for a hand, were those of her infant. Inconsistent as this assertion may appear with the whiskered body examined, it is evident Lord Nugent did not consider it wholly irrelevant; for in a letter on the subject to Mr. Murray, he says: I certainly did see, in 1828, while the pavement of the chancel of Hampden church was undergoing repair, a skeleton, which I have many reasons for believing was not John Hampden's, but that of some gentleman or lady who probably died a quiet death in bed, certainly with no wound in the wrist. Thus, after the rude violation of the Hampden sepulchre, and the mutilation of a human body, it still remained a mystery whether that body was a gentleman's or a lady's; and the problem, if any, respecting the cause of Hampden's death, was as far from solution as ever. Lord Nugent, in his Life of Hampden, makes no allusion to this opening of the grave, but adopts the statement given by Clarendon. 'In the first charge,' says he, 'Hampden received his death. He was struck in the shoulder with two carbine balls, which, breaking the bone, entered his body, and his arm hung powerless and shattered by his side.' It is remarkable that 'the patriot's grave should have been left without any monument or inscription, when such pains were taken to give him honourable burial in the sepulchre of his fathers. He is, however, commemorated by a monument against the north wall of the chancel. This memorial consists of a large sarcophagus between two weeping boys-one holding a staff, with the cap of Liberty, the other with a scroll inscribed 'MAGNA CHARTA.' Above this, in an oval medallion, is a representation in basso-relievo, of the Chalgrove fight, with a village and church in the background, and Hampden, as the prominent figure, bending over his horse, as having just received his fatal wound. Above the medallion is a genealogical-tree, bearing on its several branches the heraldic shields of the successive generations of the Hampdens and their alliances. John Hampden, the last male heir of the family, died unmarried in 1754, and is described in his epitaph as the twenty-fourth hereditary lord of Hampden manor. The property, after passing through female descendants, is now possessed by Lady Vere Cameron, who generally resides in Hampden House, which is a large handsome mansion, retaining, as Lord Nugent thought, 'traces of the different styles of architecture, from the early Norman to the Tudor, though deformed by the innovations of the eighteenth century.' It stands finely grouped among ancestral trees, on a branch of the Chiltern Hills, and commands a beautiful and extensive view over a richly wooded country, diversified by hill and dale, and lacking only water to make the scenery complete. LARGE MEN'Some,' reads Malvolio, 'are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.' Among the latter class, we may place Mr. Daniel Lambert, who died at Stamford on the 21st of July 1809, at the advanced weight of 739 pounds. In 1806, Lambert exhibited himself in London, and the following is a copy of one of his bills. Exhibition.-Mr. Daniel Lambert, of Leicester, the heaviest man that ever lived; who, at the age of thirty-six years, weighs upwards of fifty stone (fourteen pounds to the stone), or eighty-seven stones four pounds, London weight, which is ninety-one pounds more than the great Mr. Bright weighed. Mr. Lambert will see company at his house, No. 53 Piccadilly, next Albany, nearly opposite St. James's Church, from eleven to five o'clock. Tickets of Admission, One Shilling each. Lambert died suddenly. He went to bed well at night, but expired before nine o'clock of the following morning. A country newspaper of the day, aiming at fine writing, observes: Nature had endured all the trespass she could admit; the poor man's corpulency had constantly increased, until, at the time we have mentioned, the clogged machinery of life stood still, and this prodigy of mammon (sic) was numbered with the dead. His coffin contained 112 superficial feet of elm, and was 6 feet 4 inches long, 4 feet 4 inches wide, and 2 feet 4 inches deep; and the immense substance of his legs necessitated it to be made in the form of a square case. It was built upon two axle-trees, and four clog-wheels, and upon these the remains of the great man were rolled into his grave in St. Martin's Churchyard. A regular descent was made to the grave by cutting away the earth for some distance. The apartments which he occupied were on the ground-floor, as he had been long incapable of ascending a staircase. The window, and part of the wall of the room in which he died, had to be taken down, to make a passage for the coffin.' A vast multitude followed the remains to the grave, the most perfect decorum was preserved, and not the slightest accident occurred.  The 'great Mr. Bright,' mentioned in Lambert's exhibition-bill, was a grocer at Maldon, in Essex. He may partly be said to 'have been born great, for he was of a family noted for the great size and great appetites of its members. Bright enjoyed good health, married at the age of twenty-two, and had five children. An amiable mind inhabited his overgrown body. He was a cheerful companion, a kind husband, a tender father, a good master, a friendly neighbour, and an honest man. 'So,' says his biographer, 'it cannot be surprising if he was universally loved and respected.' Bright died in his thirtieth year, at the net weight of 616 pounds, or 44 stone, jockey weight. His neighbours considered that death was a happy release to him, 'and so much the more as he thought so himself, and wished to be released. His coffin was 3 feet 6 inches broad at the shoulders, and more than 3 feet in depth. A way was cut through the wall and staircase of his house to let it down into the shop. It was drawn to the church on a low-wheeled carriage, by twelve men; and was let down into the grave by an engine, fixed up on the church for that purpose, amidst a vast concourse of spectators from distant parts of the country. After his death, a wager was laid that five men, each twenty-one years of age, could he buttoned in his waistcoat. It was decided at the Black Bull Inn, at Maldon, when not only five, as proposed, but seven men were enclosed in it, without breaking a stitch or straining a button. A Mr. Palmer, landlord of the Golden Lion Inn at Brompton, in Kent, was another great man in his way, though not fit to be compared with either Bright or Lambert; weighing but 25 stone, a matter of some 380 pounds less than the great Daniel. Palmer came to London to see Lambert; yet, though five men could be buttoned in his waistcoat, he looked like a pigmy beside the great Leicestershire man. It is said that the superior grossness of his more corpulent rival in greatness, so affected Palmer as to cause his death. However that may be, he certainly died three weeks after his journey to London. A part of the Golden Lion had to be taken down to allow egress for his coffin, which was drawn to the grave in a timber wagon, as no hoarse could be procured either large enough to admit it, or sufficiently strong to bear its weight. A sad episode in the history of crime is exhibited in the forgeries and subsequent execution of Ryland, a celebrated engraver, who exercised his profession in London during the latter part of the last century. Ryland had an apprentice named John Love, who, terrified by his master's shameful death, gave up the business he was learning, and returned to his native place in Dorsetshire. At that time being exceedingly meagre and emaciated, his friends, fearing he was falling into a consumption, applied to a physician, who recommended an abundance of nutritious food, as the best medicine under the circumstances of the case. Love thus acquired a relish for the pleasures of the table, which he was soon enabled to gratify to its fullest extent, by success in business as a bookseller at Weymouth: where he soon grew as remarkably heavy and corpulent as he had previously been light and lean. So, he may have been said to have achieved his own greatness, but he did not live long to enjoy it; suffocated by fat, he died in his fortieth year, at the weight of 364 pounds. CURIOUS OLD DIVISIONS OF THE LIFE OF MANSince the mythical days of CEdipus and the Sphinx, many curious attempts have been made to partition out the life of a man into distinct periods, and to assign to each its own peculiar duties or characteristics. From a series of valuable and pleasing reflections upon youth and age, with the virtues and offices appropriate to each, to be found in Dante's prose work, called the Convito or Banquet, a philosophic commentary on certain of his own songs, Mr. Lyell, the translator of Dante's Lyrical Poems, has drawn the following table: TABLE OF DANTE'S FIVE AGES OF MAN, AND OF THE DUTY PARTICULARLY CALLED FOR IN EACH We find another such scheme, less instructive, but more amusing, in the pages of an old English poet. Many readers, to whom the name of Dante will be quite familiar, will be strangers to Thomas Tusser. He was born in Essex, about 1520, and wrote a curious book of jingling rhymes, called Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry; intended chiefly to be useful to the poorer sort-farmers, housewives, plough-boys, and the like. Southey, in whose collection of Early English Poets, Tusser's work was reprinted, relates of Lord Molesworth, that having proposed (in 1723) that a school of husbandry should be set up in every county, he advised that ' Tusser's old book of husbandry should be taught to the boys, to read, to copy, and to get by heart.' Tusser's book, the most curious book, says Southey, in the English language, was once very popular. It catalogues all weather-signs, all farm and field work, all farmer's duties, peculiarities, and wise-saws, under the several heads of the appropriate months; and winds up with a strange medley of curious household rhymes-of evil neighbours; of religions maxims and creeds; or concerning household physic-evidently meant to become popular among country labourers. Our table forms a part of this medley. Man's age divided here ye have, By 'prenticeships, from birth to grave. Not satisfied with this, Tusser is pleased to add, for the sake of variety, another edition, from a somewhat different point of view: Another division of the nature of man's age. The Ape, the Lion, the Fox, the Ass, Thus sets forth man as in a glass. Ape. Like apes we be toying, till twenty-and-one; Lion. Then hasty as lions, till forty he gone: Fox. Then wily as foxes, till threescore-and-three; Ass. Then after for asses accounted we be. Certainly, this last takes a most humiliating view of man: and in that division of his book, which the writer calls The Points of Huswifery, we are favoured with one, not much more favourable, of woman. By six times fourteen years 'prenticeship, with a lesson to the same. A lesson Then purchase some pelf By fifty and three; Or buckle thyself A drudge for to be. THE CITIZEN AND THE THIEVESThe general apparel of a citizen of London-the friendly custom of borrowing and lending and the danger and difficulty of travelling that prevailed at the period-are all humorously sketched in the following lines from a popular pamphlet, published in 1609: A citizen, for recreation's sake, To see the country would a journey take Some dozen miles, or very little more; Taking his leave with friends two months before, With drinking healths and shaking by the hand, As he had travelled to some new-found land. Well, taking horse, with very much ado, London he leaveth for a day or two: And as he rideth, meets upon the way Such as (what haste soever) bid men stay. 'Sirrah,' says one, ' stand and your purse deliver, I am a taker, thou must be a giver.' Unto a wood, hard by, they hale him in, And rifle him unto his very skin. 'Maisters,' quoth he, 'pray hear me ere you go; For you have robbed me more than you do know, My horse, in truth, I borrowed of my brother; The bridle and the saddle of another; The jerkin and the bases, be a tailor's; The scarf, I do assure you, is a sailor's; The falling band is likewise none of mine, Nor cuffs, as true as this good light cloth shine. The satin doublet, and raised velvet hose Are our churchwarden's, all the parish knows. The hoots are John the grocer's at the Swan; The spurs were lent me by a serving-man. One of my rings-that with the great red stone- In Booth, I borrowed of my gossip Joan: Her husband knows not of it, gentle men! Thus stands my ease-I pray shew favour then.' 'Why,' quoth the thieves, 'thou needst not greatly care, Since in thy loss so many bear a share; The world goes hard, and many good folks lack, Look not, at this time, for a penny back. Go, tell at London thou didst meet with four, That, rifling thee, have robbed at least a score.' |