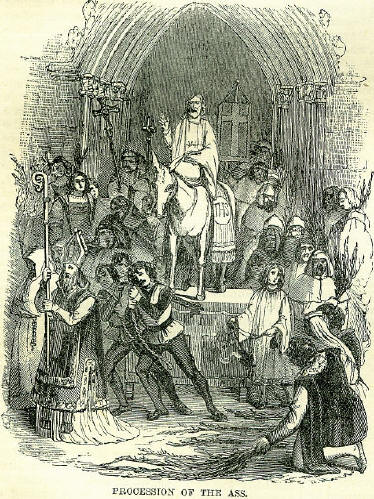

20th MarchBorn: Publius Ovidius Naso, P.P. 43; Bishop Thomas Morton, 1564; Napoleon, Duke of Reichstadt, 1811. Died: The Emperor Publius Gallienus, A.D. 268, assassinated at Milan; Henry IV, King of England, 1413, Westminster; Ernest, Duke of Luneburg, 1611; Bishop Samuel Parker, 1687, Oxford; Sir Isaac Newton, philosopher, 1727, Kensington; Frederick, Prince of Wales, 1751, Leicester House; Gilbert West, classical scholar, 1756, Chelsea; Firmin Abauzit, Genovese theological writer, 1767; Lord Chief Justice, Earl of Mansfield, 1793; H. D. Inglis (Derwent Conway), traveller, 1835; Mademoiselle Mars, celebrated French comic actress, 1847. Feast Day: St. Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne, 687. St. Wulfran, Archbishop of Sens, and apostolic missionary in Fries-land, 720. ST. CUTHBERTIn the seventh century, when the northern part of Britain was a rude woody country occupied by a few tribes of half-savage inhabitants, and Christianity was planted in only a few establishments of holy anchorets, a high promontory, round which swept the waters of the Tweed, was the seat of a small monastery, bearing the descriptive name of Muilros. A shepherd boy of the neighbouring vale of the Leader had seen this primitive abode of religious zeal and self-denial, and he became impelled by various causes to attach himself to it. Soon distinguished by his ardent, but mild piety, and zeal for the conversion of the heathen, he in time rose to be superior or prior of Muilros: and was afterwards transferred to be prior of a similar establishment on Lindisfarne, an island on the Northumbrian coast. The holy Cuthbert excelled all his brethren in devotion: he gave himself so truly to the spirit of prayer and heavenly contemplation, that he appeared to others more like an angel than a man. To attain to still greater heights in devotion, he raised a solitary cell for his own habitation in the smaller island of Farne, where at length he died on the 20th of March 687. His brother monks, raising the body of Cuthbert eleven years afterwards, that it might be placed in a conspicuous situation, found it uncorrupted and perfect: which they accepted as a miraculous proof of his saintly character. It was put into a fresh coffin, and placed on the ground, where very soon it proved the means of working miraculous cures. A hundred and seventy-four years afterwards, on the Danes invading Northumberland, the monks carried away the body of Cuthbert, and for many years wandered with it from place to place throughout Northumbria and southern Scotland, everywhere willingly supported by the devout; until at length, early in the eleventh century, it was settled at the spot where afterwards, in consequence, arose the beautiful cathedral of Durham. There, for five centuries, the shrine over the incorrupt body of Cuthbert was enriched by the offerings of the faithful: it became a blaze of gold and jewellery, dazzling to look upon. The body was inspected in 1104, and found still fresh. In 1540, when commissioners came to reduce Durham to a conformity with the new ecclesiastical system, the body of Cuthbert was again inspected, and found fresh: after which it was buried, and so remained for nearly three centuries more. In May 1827, eleven hundred and thirty-nine years after the death of the holy man on Farne island, the coffin was exhumed, and the body once more and perhaps finally examined, but this time more rigorously than before, for it was found a mere skeleton swaddled up so as to appear entire, with plaster balls in the eye-sockets to plump out that part of the visage. It thus appeared that a deception had been practised: but we are not necessarily to suppose that more than one or two persons were concerned in the trick. Most probably, at the various inspections, the examiners were so awed as only to look at the exterior of the swaddlings, the appearance of which would satisfy them that the body was still perfect within. The case is, however, a very curious one, as exhibiting a human being more important dead than alive, and as having what might be called a posthumous biography infinitely exceeding in interest that of his actual life. PALM SUNDAYThe brief popularity which Jesus experienced on his last entry into Jerusalem, when the people 'took branches of palm trees, and went forth to meet Him, crying Hosanna, &c.,' has been commemorated from an early period in the history of the Church on the Sunday preceding Easter, which day was consequently called PALM SUNDAY. Throughout the greater part of Europe, in defect of the palm tree, branches of some other tree, as box, yew, or willow, were blessed by the priests after mass, and distributed among the people, who forthwith carried them in a joyous procession, in memory of the Saviour's triumphant entry into the holy city: after which they were usually burnt, and the ashes laid aside, to be sprinkled on the heads of the congregation on the ensuing Ash Wednesday, with the priest's blessing.  Before the change of religion, the Palm Sunday customs of England were of the usual elaborate character. The flowers and branches designed to be used by the clergy were laid upon the high altar; those to be used by the laity upon the south step of the altar. The priest, arrayed in a red cope, proceeded to consecrate them by a prayer, beginning, 'I conjure thee, thou creature of flowers and branches, in the name of Cod the Father,' &c. This was to displace the devil or his influences, if he or they should chance to be lurking in or about the branches. He then prayed- 'We humbly beseech thee that thy truth may [here a sign of the cross] sanctify this creature of flowers and branches, and slips of palms, or boughs of trees, which we offer,' &c. The flowers and branches were then fumed with frankincense from censers, after which there were prayers and sprinklings with holy water. The flowers and branches being then distributed, the procession commenced, in which the most conspicuous figures were two priests bearing a crucifix. When the procession had moved through the town, it returned to church, where mass was performed, the communion taken by the priests, and the branches and flowers offered at the altar. In the extreme desire manifested under the ancient religion to realize all the particulars of Christ's passion, it was customary in some places to introduce into the procession a wooden figure of an ass, mounted on wheels, with a wooden human figure riding upon it, to represent the Saviour. Previous to starting, a priest declared before the people who was here represented, and what he had done for them: also, how he had come into Jerusalem thus mounted, and how the people had strewn the ground as he went with palm branches. Then it set out, and the multitude threw their willow branches before it as it passed, till it was sometimes a difficulty for it to move: two priests singing psalms before it, and all the people shouting in great excitement. Not less eager were the strewers of the willow branches to gather them up again after the ass had passed over them, for these twigs were deemed an infallible protection against storms and lightning during the ensuing year. Another custom of the day was to cast cakes from the steeple of the parish. church, the boys scrambling for them below, to the great amusement of the bystanders. Latterly, an angel appears to have been introduced as a figure in the pro-cession: in the accounts of St. Andrew Hubbard's parish in London, under 1520, there is an item of eightpence for the hire of an angel to serve on this occasion. Angels, however, could fall in more ways than one, for, in 1537, the hire was only fourpence. Crosses of palm were made and blessed by the priests, and sold to the people as safeguards against disease. In Cornwall, the peasantry carried these crosses to 'our lady of Nantswell,' where, after a gift to the priest, they were allowed to throw the crosses into the well, when, if they floated, it was argued that the thrower would outlive the year: if they sunk, that he would not. It was a saying that he who had not a palm in his hand on Palm Sunday, would have his hand cut off. After the Reformation, 1536, Henry VIII declared the carrying of palms on this day to be one of those ceremonies not to be contemned or dropped. The custom was kept up by the clergy till the reign of Edward VI., when it was left to the voluntary observance of the people. Fuller, who wrote in the ensuing age, speaks of it respectfully, as 'in memory of the receiving of Christ into Hierusalem a little before his death, and that we may have the same desire to receive him into our hearts.' It has continued down to a recent period, if not to the present day, to be customary in many parts of England to go a-palming on the Saturday before Palm Sunday: that is, young persons go to the woods for slips of willow, which seems to be the tree chiefly employed in England as a substitute for the palm, on which account it often receives the latter name. They return with slips in their hats or button-holes, or a sprig in their mouths, bearing the branches in their hands. Not many years ago, one stall-woman in Covent-garden. market supplied the article to a few customers, many of whom, perhaps, scarcely knew what it meant. Slips of the willow, with its velvety buds, are still stuck up on this day in some rural parish churches in England. The ceremonies of Easter at Rome-of what is there called Holy Week-commence on Palm Sunday. To witness these rites, there are seldom fewer than ten thousand foreigners assembled in the city, a large proportion of them English and American, and of course Protestant. During Holy Week, the shops are kept open, and concerts and other amusements are given: but theatrical performances are forbidden. The chief external differences are in the churches, where altars, crucifixes, and pictures are generally put in mourning. About nine on Palm Sunday morning, St. Peter's having received a great crowd of people, all in their best attire, one of the papal regiments enters, and forms a clear passage up the central aisle. Shortly afterwards the 'noble guard,' as it is called, of the Pope-a superior body of men -takes its place, and the corps diplomatique and distinguished ecclesiastics arrive, all taking their respective seats in rows in the space behind the high altar, which is draped and fitted up with carpets for the occasion. The Pope's chief sacristan now brings in an armful of so-called palms, and places them on the altar. These are stalks about three feet long, resembling a walking-cane dressed up in scraps of yellow straw: they are sticks with bleached palm leaves tied on them in a tasteful but quite artificial way. The preparation of these substitutes for the palm is a matter of heritage, with which a story is connected. When Sextus V (1585-90) undertook to erect in the open space in front of St. Peter's, the tall Egyptian obelisk which formerly adorned Nero's circus, he forbade any one to speak on pain of death, lest the attention of the workmen should be diverted from their arduous task. A naval officer of St. Remo, who happened to be present, foreseeing that the ropes would take fire, cried out to 'apply water.' He was immediately arrested, and con-ducted before the pontiff. As the cry had saved the ropes, Sextus could not enforce the decree, and to shew his munificence he offered the transgressor his choice of a reward. Those who have observed the great abundance of palms which grow in the neighbourhood of St. Remo, between Nice and Genoa, will not be surprised to hear that the wish of the officer was to enjoy the privilege of supplying the pontifical ceremonies with palms. The Pope granted him the exclusive right, and it is still enjoyed by one of his family. At 9.30 a burst of music is heard from the choir, the soldiers present arms, all are on the tip-toe of expectation, and a procession enters from a side chapel near the doorway. All eyes are turned in this direction, and the Pope is seen borne up the centre of the magnificent basilica in his sedia gestatoria. This chair of state is fixed on two long poles covered with red velvet, and the bearers are twelve officials, six before and six behind. They bear the ends of the poles on their shoulders, and walk so steadily as not to cause any uneasy motion. On this occasion, and always keeping in mind that the church is in mourning, the Pope is plainly attired, and his mitre is white and without ornament. There are also wanting the flabelli, or large fans of feathers, which are carried on Easter Sunday. Thus slowly advancing, and by the movement of his hand giving his benediction to the bowing multitude, the Pope is carried to the front of his throne at the further end of the church. Descending from his sedia gestatoria, his Holiness, after some intermediate ceremonies and singing, proceeds to bless the palms, which are brought to him from the altar. This blessing is effected by his reading certain prayers, and incensing the palms three times. An embroidered apron is now placed over the Pope's knees, and the cardinals in turn receive a palm from him, kissing the palm, his right hand, and knee. The bishops kiss the palm which. they receive and his right knee: and the mitred abbots and others kiss the palm and his foot. Palms are now more freely distributed by sacristans, till at length they reach those among the lay nobility who desire to have one. The ceremony concludes by reading additional prayers, and more particularly by chanting and singing. The Benedictus qui venit is very finely executed. In conclusion, low mass is performed by one of the bishops present, and the Pope, getting into his sedia gestatoria, is carried with the same gravity back to the chapel whence he issued, and which communicates with his residence in the Vatican. The entire ceremonial lasts about three hours, but many, to see it, endure the fatigue of standing five to six hours. Among the strangers present, ladies alone are favoured with seats, but they must be in dark dresses, and with black veils on their heads instead of bonnets.  Until lately, there existed at Caistor, in Lincolnshire, a Palm Sunday custom of a very quaint nature, and which could not have been kept up if it had not been connected with a tenure of property. It has been thus described: 'A person representing the proprietor of the estate of Broughton comes into the porch of Caistor Church while the first lesson is reading, and three times cracks a gad-whip, which he then folds neatly up. Retiring for the moment to a seat in the church, he must come during the second lesson to the minister, with the whip held upright, and at its upper end a purse with thirty pieces of silver contained in it; then he must kneel before the clergyman, wave the whip thrice round his head, and so remain till the end of the lesson, after which he retires. The precise origin of this custom has not been ascertained. We can see in the purse and its thirty pieces of silver a reference to the misdeeds of Judas Iscariot: but why the use of a whip? Of this the only explanation which conjecture has hitherto been able to supply, refers us back to the ancient custom of the Procession of the Ass, before described. Of that procession it is supposed that the gad-whip of Caistor is a sole-surviving relic. The term gad-whip has been a puzzle to English antiquaries: but a gad [goad] for driving horses, was in use in Scotland so lately as the days of Burns, who alludes to it. A portraiture of the gad-whip employed on a recent occasion, with the purse at its upper end, is here presented. The land which was held by the singular tenure now described, having been sold in 1845, the custom ceased. THE DEATH OF HENRY THE FOURTH. AMBIGUOUS PROPHECIESRobert Fabian, alderman and sheriff of London, a man of learning, a poet, and historian, in his Concordance of Stories (a history commencing with the fabulous Brute, and ending in the reign of Henry VII), was the first to relate the since often-quoted account of the circumstances attending the death of the fourth Henry: 'In this year' [1412], says the worthy citizen, 'and twentieth day of the month of November, was a great council holden at the Whitefriars of London, by the which it was, among other things, concluded, that for the King's great journey he intended to take in visiting the Holy Sepulchre of our Lord, certain galleys of war should be made, and other purveyance concerning the same journey. Whereupon, all hasty and possible speed was made, but after the feast of Christmas, while he was making his prayers at St. Edward's shrine, to take there his leave, and so to speed him on his journey, he became so sick, that such as were about him feared that he would have died right there: wherefore they, for his comfort, bore him into the Abbot's place, and lodged him in a chamber; and there, upon a pallet, laid him before the fire, where he lay in great agony a certain of time.' 'At length, when he was come to himself, not knowing where he was, freyned [inquired] of such as then were about him, what place that was: the which shewed to him, that it belonged unto the Abbot of Westminster: and for he felt himself so sick, he commanded to ask if that chamber had any special name. Whereunto it was answered, that it was named Jerusalem. Then said the king-'Loving be to the Father of Heaven, for now I know I shall die in this chamber, according to the prophecy of me before said that I should die in Jerusalem:' and so after, he made himself ready, and died shortly after, upon the day of St. Cuthbert, or the twentieth day of March 1413.' This story has been frequently told with variations of places and persons; among the rest, of Gerbert, Pope Sylvester II, who died in 1003. Gerbert was a native of France, but, being imbued with a strong thirst for knowledge, he pursued his studies at Seville, then the great seat of learning among the Moors of Spain. Becoming an eminent mathematician and astronomer, he introduced the use of the Arabic numerals to the Christian nations of Europe; and, in consequence, acquired the name and fame of a most potent necromancer. So, as the tale is told, Gerbert, being very anxious to inquire into the future, but at the same time determined not to be cheated, by what Macbeth terms the juggling fiends, long considered how he could effect his purpose. At last he hit upon a plan, which he put into execution by making, under certain favourable planetary conjunctions, a brazen head, and endowing it with speech. But still dreading diabolical deception, he gave the head power to utter only two words-plain 'yes' and 'no.' Now, there were two all-important questions, to which Gerbert anxiously desired responses. The first, prompted by ambition, regarded his advancement to the papal chair: the second referred to the length of his life,-for Gerbert, in his pursuit of magical knowledge, had entered into certain engagements with a certain party who shall be nameless: which rendered it very desirable that his life should reach to the longest possible span, the reversion, so to speak, being a very uncomfortable prospect. Accordingly Gerbert asked the head, 'Shall I become Pope? 'The head replied, 'Yes!' The next question was, 'Shall I die before I chant mass in Jerusalem?' The answer was, `No!' Of course, Gerbert had previously determined, that if the answer should be in the negative, he would take good care never to go to Jerusalem. But the certain party, previously hinted at, is not so easily cheated. Gerbert became Pope Sylvester, and one day while chanting mass in a church at Rome found himself suddenly very ill. On making inquiry, he learned that the church he was then in was named Jerusalem. At once, knowing his fate, he made preparations for his approaching end, which took place in a very short time. Malispini relates in his Florentine history that the Emperor Frederick II had been warned, by a soothsayer, that he would die a violent death in Firenze (Florence). So Frederick avoided Firenze, and, that there might be no mistake about the matter, he shunned the town of Faenza also. But he thought there was no danger in visiting Firenzuolo, in the Appenines. There he was treacherously murdered in 1250, by his illegitimate son Manfred. Thus, says Malispini, he was unable to prevent the fulfilment of the prophecy. The old English chroniclers tell a somewhat similar story of an Earl of Pembroke, who, being informed that he would be slain at Warwick, solicited and obtained the governorship of Berwick-upon-Tweed; to the end that he might not have an opportunity of even approaching the fatal district of Warwickshire. But a short time afterwards, the Earl being killed in repelling an invasion of the Scots, it was discovered that Barwick, as it was then pronounced, was the place meant by the quibbling prophet. The period of the death of Henry IV was one of great political excitement, and consequently highly favourable to the propagation of prophecies of all kinds. The deposition of Richard and usurpation of Henry were said to have been foretold, many centuries previous, by the enchanter Merlin; and both parties, during the desolating civil wars that ensued, invented prophecies whenever it suited their purpose. Two prophecies of the ambiguous kind, 'equivocations of the fiend that lies like truth,' are recorded by the historians of the wars of the roses, and noticed by Shakspeare. William de la Pole, first Duke of Suffolk, had been warned by a wizard, to beware of water and avoid the tower. So when his fall came, and he was ordered to leave England in three days, he made all haste from London, on his way to France, naturally supposing that the Tower of London, to which traitors were conveyed by water, was the place of danger indicated. On his passage across the Channel, however, he was captured by a ship named Nicholas of the Tower, commanded by a man surnamed Walter. Suffolk, asking this captain to be held to ransom, says: Look on my George, I am a gentleman; Rate me at what thou wilt, thou shalt be paid. Captain: And so am I: my name is Walter Whitmore- How now? why start'st thou? What, doth death affright? Suffolk: Thy name affrights me, in whose sound is death; A cunning man did calculate my birth, And told me that by water I should die; Yet let not this make thee be bloody-minded, Thy name is Gualtier being rightly sounded. Of course, the prophecy was fulfilled by Whitmore beheading the Duke. The other instance refers to Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, who is said to have consulted Margery Jourdemayne, the celebrated witch of Eye, with respect to his conduct and fate during the impending conflicts. She told him that he would be defeated and slain at a castle: but as long as he arrayed his forces and fought in the open field, he would be victorious and safe from harm. Shakspeare represents her familiar spirit saying: Let him shun castles. Safer shall he be on the sandy plain Than where castles mounted stand. After the first battle of St. Albans, when the trembling monks crept from their cells to succour the wounded and inter the slain, they found the dead body of Somerset lying at the threshold of a mean alehouse, the sign of which was a castle. And thus, Underneath an alehouse' paltry sign, The Castle, in St. Albans, Somerset Hath made the wizard famous in his death. Cardinal Wolsey, it is said, had been warned to beware of Kingston. And supposing that the town of Kingston was indicated by the person who gave the warning, the cardinal took care never to pass through that town: preferring to go many miles about, though it lay in the direct road between his palaces of Esher and Hampton Court. But after his fall, when arrested by Sir William Kingston, and taken to the Abbey of Leicester, he said, 'Father Abbot, I am come to leave my bones among you,' for he knew that his end was at hand. SIR ISAAC NEWTONIt was an equally just and generous thing of Pope to say of Newton, that his life and manners would make as great a discovery of virtue and goodness and rectitude of heart, as his works have done of penetration and the utmost stretch of human knowledge. Assuredly, Sir Isaac was the perfection of philosophic simplicity. His plays in childhood were mechanical experiments. His relaxations in mature life from hard thinking and investigation, were dabblings in ancient chronology and the mysteries of the Apocalypse. The passions of other men, for love, for money, for power, were in him non-existent: all his energies were devoted to pure study. Sir David Brewster, in his able Life of Newton, has successfully defended his character from imputations brought upon it by Flamsteed. He has also, however, printed a letter attributed to Sir Isaac -a love-letter-a love-letter written when he was sixty, proposing marriage to the widow of his friend Sir William Norris. It is quite impossible for us to believe that the author of the Principia ever wrote such a letter, until more decisive proof of the fact can be adduced, and scarcely even then. The subjoined autograph of Sir Isaac is furnished to us from an inedited letter. It precisely resembles one which we possess, extracted from the books of the Mint, of which Sir Isaac was master. LORD CHIEF JUSTICE, EARL OF MANSFIELDLord Campbell, in his Lives of the Chief Justices, has traced the career of William Murray, Earl of Mansfield, with great precision and a good deal of fresh light. He shews us how he came of a very poor Scotch peer's family, the eleventh of a brood of fourteen children, reared on oat-meal porridge in the old mansion of Scoon, near Perth, which our learned author persists in calling a castle, while it was nominally a palace, but in reality a plain old-fashioned house. One particular of some importance in the Chief Justice's history does not seem to have been known to his biographer-that, while the father (David, fifth Viscount Stormont) was a good-for-little man of fashion, the mother, Marjory Scott, was a woman of ability, who was supposed to have brought into the Stormont family any talent-and it is not little-which it has since exhibited, including that of the illustrious Chief Justice. She came of the Scots, (so they spelt their name) of Scotstarvit, in Fife, a race which produced an eminent patron of literature in Sir John Scot, Director of the Chancery in the time of Charles I., and author of a bitingly clever tract, entitled The Staggering State of Scots Statesmen, which was devoted to the amiable purpose of shewing all the public and domestic troubles that had fallen upon official persons in Scotland from the days of Mary downward. Marjory, Viscountess of Stormont, was the great-granddaughter of Sir John, whose wife again was of a family of talent, Drummond of Hawthornden. In the history of the lineage of intellect we could scarcely find a clearer pretension to ability than what lay at the door of the youth William Murray. It is not our business to trace, as Lord Campbell has done, the steps by which this youth rose at the English bar, attained office, prosecuted Scotch peers, his cousins, for treason against King George, became a great parliamentary orator, and the highest criminal judge in the kingdom, and, without political office, was the director of several successive cabinets. We may remark, however, what has hitherto been comparatively slurred, that the Jacobitism of Murray's family was unquestionable. His father was fully expected to join in the insurrection of 1715, and he was thought to avoid doing so in a way not very creditable to him. An elder brother of William was in the service of 'the Pretender' abroad. When Charles Edward, in 1745, came to Perth, he lodged in the house of Lord Stormont, and one of the ladies of the family (sister to the Chief Justice) made his Royal Highness's bed with her own fair hands. After this, the remark of Lovat at his trial to the Solicitor-General, that his mother had been very kind to the Frasers as they marched through Perth, may well be accepted as a simple reference to a matter of fact. The most important point in the life of the Lord Chief Justice, all things considered, is his transplantation to England. His natural destiny was, as Lord Campbell remarks, to have lived the life of an idle younger brother, fishing in the Tay, and hunting deer in Atholl. How comes it that he found a footing in the south? On this subject, Murray himself must have studied to preserve an obscurity. It was given out that he had been brought to London at three years of age, and hence the remark of Johnson to Boswell, that much might be made of a Scotsman 'if caught young.' To Lord Campbell belongs the credit of ascertaining that young Murray in reality received his juvenile education at the Grammar-school of Perth, and did not move to England till the age of fourteen, by which time he had shown great capacity, being, for one thing, able to converse in Latin. The Jacobite elder brother was the means of bringing 'Willié southward. As a Scotch member during the Harley and Bolingbroke administration, he had gained the friendship of Atterbury, then Dean of Westminster. In the Stuart service himself, and anxious to bring Willie into the same career, he recommended that he should be removed to Westminster school, and brought up under the eye of the dean: professing to believe that he was sure of a scholarship at Christchurch, and of all desirable advancement that his talent fitted him for. Willie was accordingly sent on horse-back by a tedious journey to London, in the spring of 1718, and never saw his country or his parents again. In a year he had obtained a king's scholarship, and it is suspected that the interest of Atterbury was the means of his getting it. Lord Campbell duly tells us of the elegant elocution to which Murray attained. He succeeded, it seems, in getting rid of his Scotch accent: and yet 'there were some shibboleth words which he could never pronounce properly to his dying day: for example, he converted regiment into reg'ment; at dinner he asked not for bread, but brid; and in calling over the bar, he did not say, 'Mr. Solicitor,' but 'Mr. Soleester, will you move anything?' |