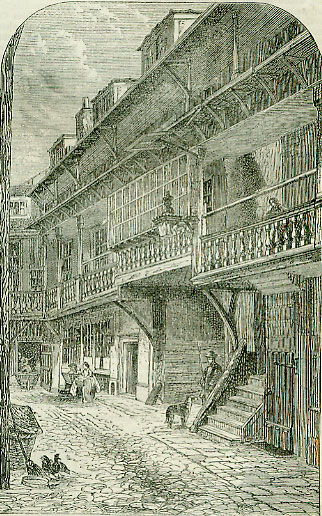

20th FebruaryBorn: Francois-Marie Arouet de Voltaire, poet, dramatist, historical and philosophical writer, 1694, Chatenay: David Garrick, actor and dramatist, 1716, Hereford: Charles Dalloway, 1763, Bristol. Died: Archbishop Arundel, 1413-14, Canterbury; Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper, 1579, York House, Strand; Dorothy Sidney, Countess of Sunderland, 1684, Brington, Mrs. Elizabeth Rowe, philanthropic-religious writer, 1737; Charles III (of Savoy), 1773; Joseph II (Emperor), 1790; Dr. John Moore, novelist, 1802, Richmond; Richard Gough, antiquary, 1809, Wormley: Andreas Hofer, Tyrolese patriot, shot by the French, 1810: Joseph Hume, statesman, 1855. Feast Day: Saints Tyrannio, Zenobius, and others, martyrs in Phoenicia, about 310. St. Sadoth, bishop of Scleucia and Ctesiphon, with 128 companions, martyrs, 342. St. Eleutherius, bishop of Tournay, martyr, 522. St. Mildred, virgin abbess in Thanet, 7th century. St. Eucherius, bishop of Orleans, 743. St. Ulrick, of England, 1154. JOSEPH HUMEThe name of Joseph Hume has become so inseparably associated with his long-continued exertions to check extravagance in the use of public money, that most persons will hear with a feeling of surprise that he was in reality disposed to a liberal use of the state funds wherever a good object was to be served, and especially if that object involved the advancement of knowledge among the people. The Earl of Ellesmere, in his address to the Geographical Society, in 1855, bore strong testimony to the help which Mr. Hume had given in promoting the claim of that body for assistance towards giving it a better place of meeting, and enabling it to throw open to the public the use of its 'instruments of research and instruction.' The present writer can add a grateful testimony, in regard to the Scottish Society of Antiquaries. That body, being a few years ago hardly rich enough to keep a person to shew its valuable museum, a proposal was made that it should hand. its collection over to the state, who might then keep it open for the instruction and gratification of the public at its own expense. Mr. Hume became satisfied that the proposal was an honest one, calculated to prove serviceable to the public and the Society had no such friend and advocate as he in getting the transaction with the Treasury effected. The result has been such as fully to justify the zeal he spewed on the occasion. Mr. Hume was a native of Montrose, made his way through poverty to the education of a physician, and, realizing some wealth in India, devoted himself from about the age of forty to political life. As a member of Parliament, it was the sole study of this remarkable man to protect and advance the interests of' the public: he specially applied himself, in the earlier part of his career, to the advocacy of an economical use of the public purse. He met with torrents of abuse and ridicule from those interested in opposite objects, and he encountered many disappointments: but nothing ever daunted or disheartened him. Within an hour of' a parliamentary defeat, he would be engaged in merry play with his children, having entirely cast away all sense of mortification. The perfect single-heartedness and honesty of Joseph Hume in time gained upon his greatest enemies, and he died in the enjoyment of the respect of all classes of politicians. TWO POET FELONSOn the 20th of February 1719, the vulgar death of felons was suffered at Tyburn by two men different in some respects from ordinary criminals, Usher Gahagan and Terence Conner, both of them natives of Ireland. They were young men of respectable connections and excellent education: they had even shown what might be called promising talents. Gahagan, on coming to London, offered to translate Pope's Essay on Man into Latin for the booksellers, and, from anything that appears, he would have performed the task in a manner above mediocrity. There was, however, a moral deficiency in both of these young men. Falling into vicious courses, and failing to supply themselves with money by honest means, they were drawn by a fellow-countryman named Coffey into a practice of filing the coin of the realm, a crime then considered as high treason. For a time, the business prospered, but the usual detection came. It came in a rather singular manner. A teller in the Bank of England, who had observed them frequently drawing coin from the bank, became suspicions of them, and communicated his suspicious to the governors. Under direction from these gentlemen, he, on the next occasion, asked the guilty trio to drink wine with him in the evening at the Crown Tavern, near Cripplegate. As had been calculated upon, the wine and familiar discourse opened the hearts of the men, and Gahagan imparted to the teller the secret of their life, and concluded by pressing him to become a confederate in their plans. Their apprehension followed, and, on Coffey's evidence, the two others were found guilty and condemned to death. Just at that time, the young Prince George (afterwards George III) and his younger brother Edward had appeared in the characters of Cato and Juba, in a boy-acted play at court. Poor Gahagan sent a poetical address to the young prince, hoping for some intercession in his behalf. It was as well expressed and as well rhymed as most poetry of that age. After some of the usual compliments, he proceeded thus: Roused with the thought and impotently vain, I now would launch into a nobler strain; But see! the captive muse forbids the lays, Unfit to stretch the merit I would praise. Such at whose heels no galling shackles ring, May raise the voice, and boldly touch the string; Cramped hand and foot while I in gaol must stay, Dreading each hour the execution day; Pent up in den, opprobrious alms to crave, No Delphic cell, ye gods, nor sybil's cave; Nor will my Pegasus obey the rod, With massy iron barbarously shod, & Conner in like verse claimed the intercession of the Duchess of Queensberry, describing in piteous terms the hard usage and meagre fare now meted out to him, and entreating that she, who had been the, protectress of Gay, would not calmly sec another poet hanged. All was in vain. WARWICK LANEFew of the thoroughfares of old London have undergone such mutations of fortune as may be traced in Warwick-lane, once the site of the house of the famed Beauchamps, Earls of Warwick, afterwards distinguished by including in its precincts the College of Physicians, now solely remarkable for an abundance of those private shambles which are still permitted to disgrace the English metropolis. In the coroners' rolls of five centuries ago, we read of mortal accidents which befell youths in attempting to steal apples in the neighbouring orchards of Paternoster-row and Ivy-lane, then periodically redolent of fruit-blossoms. 'Warwick Inn, as the ancient house was called, was, in the 28th of Henry VI (about 1450) possessed by Cecily, Duchess of Warwick. Eight years later, when the greater estates of the realm were called up to London, Richard Neville, Earl of 'Warwick, the King-maker: 'came with 600 men, all in red jackets, embroidered with ragged staves before and behind, and was lodged in Warwick-lane; in whose house there was oftentimes six oxen eaten at a breakfast, and every tavern was full of his meat; for he that had any acquaintance in that house, might have there so much of sodden and roast meat as he could prick and carry on a long dagger.' The Great Fire swept away the Warwick-lane of Stow's time; and when it was rebuilt, there was placed upon the house at its north-west end, a has-relief of Guy, Earl of Warwick, in memory of the princely owners of the inn, with the date '1668' upon it. This memorial-stone, which was renewed in 1817, by J. Deykes, architect, is a counterpart of the figure in the chapel of St Mary Magdalen, in Guy's Cliff, near Warwick. The College of Physicians, built by Wren to replace a previous fabric burnt down in the Great Fire, may still be seen on the west side of the lane, but sunk into the condition of a butcher's shop. Though in a confined situation, it seems to have formerly been considered an impressive structure, the exterior being thus described in Garth's witty satire of the Dispensary: Not far from that most celebrated place, Where angry Justice shews her awful face, Where little villains must submit to fate, That great ones may enjoy the world in state, There stands a dome majestic to the sight, And sumptuous arches bear its awful height; A golden globe, placed high with artful skill, Seems to the distant sight a gilded pill.' This simile is a happy one; though Mr. Elmes, Wren's biographer, ingeniously suggests that the gilt globe was perhaps intended to intimate the universality of the healing art. Here the physicians met until the year 1825, when they removed to their newly-built College in Pall Mall East. The interior of the edifice in Warwick-lane was convenient and sumptuous; and one of the minute accounts tells us that in the garrets were dried the herbs for the use of the Dispensary. The College buildings were next let to the Equitable Loan (or Pawnbroking) Company; next to Messrs. Tyler, braziers, and as a meat-market: oddly enough, on the left of the entrance portico, beneath a bell-handle there remains the inscription ' Mr. Lawrence, Surgeon,' along with the words 'Night Bell,' recalling the days when the house belonged to a learned institution. We must, however, take a glance at the statues of Charles II. and Sir John Cutler, within the court; especially as the latter assists to expose an act of public meanness. It appears by the College books that, in 1674, Sir John Cutler promised to bear the expense of a specified part of the new building: the committee thanked him, and in 1680, statues of the King and Sir John were voted by the members: nine years afterwards, when the College was completed, it was resolved to borrow money of Sir John, to discharge the College debt; what the sum was is not specified; it appears, however, that in 1699, Sir John's executors made a demand on the College for £7,000, supposed to include money actually lent, money pretended to be given, and interest on both. The executors accepted £2,000, and dropped their claim for the other five. The statue was allowed to stand; but the inscription, 'Omnis Cutleri cedat Labor Amphitheatre,' was very properly obliterated.  In the lane are two old galleried inns, which carry us back to the broad-wheeled travelling wagons of our forefathers. About midway, on the east side, is the Bell Inn, where the pious Archbishop Leighton ended his earthly pilgrimage, according to his wish, which Bishop Burnet states him to have thus expressed in the same peaceful and moderate spirit, as that by which, in the troublous times of the Commonwealth, Leighton won the affections of even the most rigid Presbyterians. 'He used often to say, that, if he were to choose a place to die in, it should be an inn: it looking like a pilgrim's going home, to whom this world was all as an inn, and who was weary of the noise and confusion in it. He added that the officious tenderness and care of friends was an entanglement to a dying man: and that the unconcerned attendance of those that could be procured in such a place would give less disturbance. And he obtained what he desired: for he died [1684] at the Bell Inn, in Warwick-lane Own Times. Dr. Fall, who was well acquainted with Leighton, after a glowing eulogy on his holy life and 'heavenly converse,' proceeds: 'Such a life, we may easily persuade ourselves, must make the thought of death not only tolerable, but desirable. Accordingly, it had this noble effect upon him. In a paper left under his own hand, (since lost,) he bespeaks that day in .a most glorious and triumphant manner; his expressions seem rapturous and ecstatic, as though his wishes and desires had anticipated the real and solemn celebration of his nuptials with the Lamb of God. He sometimes expressed his desire of not being troublesome to his friends at his death; and God gratified to the full his modest humble choice: he dying at an inn in his sleep.' Somewhat lower in the Lane is the street leading to Newgate-market, which Gay has thus signalized: Shall the large mutton smoke upon your boards? Such Newgate's copious market best affords. Before the Great Fire, this market was kept in Newgate-street, where there was a market-house formed, and a middle row of sheds, which afterwards were converted into houses, and inhabited by butchers, tripe-sellers, &c. The stalls in the open street grew dangerous, and were accordingly removed into the open space between Newgate-street and Paternoster-row, formerly the orchards already mentioned: and here were the houses of the Prebends of St Paul's, overgrown with ivy: whence ivy-lane takes its name, although amidst the turmoil of the market, with the massive dome of St Paul's on one side, and that of the old College of Physicians on the other, it is hard to associate the place with the domain of a nymph so lovely as Pomona. The other galleried inn of Warwick-lane is the Oxford Arms, within a recess on the west side, and nearly adjoining to the residentiary houses of St Paul's in Amen-corner. It is one of the best specimens of the old London inns remaining in the metropolis. As you advance you observe a red brick pedimented facade of the time of Charles II, beneath which you enter the inn-yard, which has, on three of its sides, two stories of balustraded wooden galleries, with exterior staircases leading to the chambers on each floor: the fourth side being occupied by stabling, built against part of old London wall. The house was an inn with the sign of the Oxford Arms before the Great Fire, as appears by the following advertisement in the London Gazette for March, 1672-3, No. 762: 'These are to give notice, that Edward Bartlett, Oxford carrier, hath removed his inn, in London, from the Swan, at Holborn-bridge, to the Oxford Arms, in Warwick-lane, where he did inn before the Fire: his coaches and wagons going forth on their usual days,-Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. He hath also a hearse, with all things convenient, to carry a corpse to any part of England.' The Oxford Arms was not part of the Earl of Warwick's property, but belonged to the Dean and Chapter of St Paul's, who hold it to this day. From the inn premises is a door opening into one of the back yards of the residentiary houses, and it is stated that, during the riots of 1780, this passage facilitated the escape of certain Roman Catholics, who then frequented the Oxford. Arms, on their being attacked by the mob: for which reason, as is said, by a clause inserted in the Oxford Arms lease, that door is forbidden to be closed up. This inn appears to have been longer frequented by carriers, wagoners, and stage-coaches, than the Bell Inn, on the east side of the Lane; for in the list in Delaune's Present State of London, 1690, the Oxford Arms occurs frequently, but mention is not made of the Pell Inn. 'At the Oxford Arms, in Warwick-lane,' lived John Roberts, the bookseller, from whose shop issued the majority of the squibs and libels on Pope. In Warwick-square, about midway on the west side of the Lane, was the early office of the Public Ledger newspaper, in which Goldsmith wrote his Citizen of the World!, at two guineas per week; and here succeeded to a share in the property John Crowder, who, by diligent habits, rose to be alderman of the ward (Farringdon Within), and Lord Mayor in 1S29-30. The London Pucket (evening paper) was also Crowder's property. The Independent Whig was likewise localized in the square: and at the south-west corner was the printing-office of the inflexible John Wheble, who befriended John Britton, when cellarman to a wine-merchant, and set him to write the Beauties of Wiltshire. Wheble was, in 1771, apprehended for abusing the house of Commons, in his Middlesex Journal, but was discharged by Wilkes: of a better complexion was his County Chronicle, and the Sporting Magazine, which he commenced with John Barris, the bookseller. in this dull square, also, was the office of Mr. Wilde, solicitor, the father of Lord Chancellor Truro, who here mounted the office-stool en route to the Woolsack. HAPPY ACCIDENTSIn 1684, a poor boy, apprenticed to a weaver at his native village of Wickwar, in Gloucestershire, in carrying, according to custom on a certain day in the year, a dish called 'whitepot' to the baker's, let it fall and broke it, and fearing to face his mistress, ran away to London, where he prospered, and, remembering his native village, founded the schools there which bear his name. At Monmouth, tradition relates that one William Jones left that place to become a shopboy to a London merchant, in the time of James I, and, by his good conduct, rose first to the counting-house, and then to a partnership in the concern: and having realized a large fortune, came back in the disguise of is pauper, first to his native place, Newland, in Gloucestershire, from whence, having been ill received there, he betook himself to Monmouth, and meeting with kindness among his old friends, he bestowed £9,000 in founding a free grammar-school. |