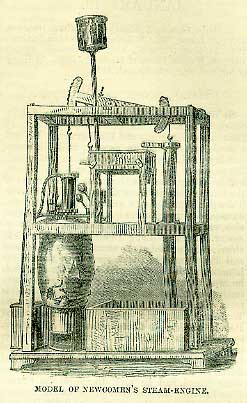

19th JanuaryBorn: Nicholas Copernicus, 1472; James Watt, 1736. Died: Charles Earl of Dorset, 1706; William Congreve, poet, 1729; Thomas Ruddiman, grammarian, 1757; Isaac Disraeli, miscellaneous writer, 1848. Feast Day: SS Maris, Martha, Audifax, and Abachum, martyrs, 270. St. Lomer, 593. St. Blaithmaic, abbot in Scotland, 793. St. Knut (Canutus), king of Denmark, martyr, 1036. St. Wulstan, bishop of Worcester, 1095. St. Henry of England, martyr in Finland, 1151. WULSTAN, BISHOP OF WORCESTERSt. Wulstan was the last saint of the Anglo-Saxon Church, the link between the old English Church and hierarchy and the Norman. He was a monk, indeed, and an ascetic; still, his vocation lay not in the school or cloister, but among the people of the market-place and the village, and he rather dwelt on the great broad truths of the Gospel than followed them into their results. Though a thane's son, a series of unexpected circumstances brought him into the religious profession, and he became prior of a monastery at Worcester. Born at Long Itchington, in Warwickshire, and educated at the monasteries of Evesham and Peterborough, the latter one of the richest houses and the most famous schools in England, he was thoughtful above his years, and voluntarily submitted to exercises and self-denials from which other children were excused. To Wulstan, the holy monk, the proud Earl Harold once went thirty miles out of his way, to make his confession to him, and beg his prayers. He was a man of kind yet blunt and homely speech, and delighted in his devotional duties; the common people looked upon him as their friend, and he used. to sit at the church door listening to complaints, redressing wrongs, helping those who were in trouble, and giving advice, spiritual and temporal. Every Sunday and great festival he preached to the people: his words seemed to be the voice of thunder, and he drew together vast crowds, wherever he had to dedicate a church. As an example of his practical preaching, it is related that, in reproving the greediness which was a common fault of that day, Wulstan confessed that a savory roast goose which was preparing for his dinner, had once so taken up his thoughts, that he could not attend to the service he was performing, but that he had punished himself for it, and given up the use of meat in consequence. At length, in 1062, two Roman cardinals came to Worcester, with Aldred the late bishop, now Archbishop of York; they spent the whole Lent at the Cathedral monastery, where Wulstan was prior, and they were so impressed with his austere and hardworking way of life, that partly by their recommendation, as well as the popular voice at Worcester, Wulstan was elected to the vacant bishopric. He heard of this with sorrow and vexation, declaring that he would rather lose his head than be made a bishop; but he yielded to the stern rebuke of an aged hermit, and received the pastoral staff from the hands of Edward the Confessor. The Normans, when they came, thought him, like his church, old-fashioned and homely; but they admired, though in an Englishman, his unworldly and active life, which was not that of study and thoughtful retirement, but of ministering to the common people, supplying the deficiencies of the parochial clergy, and preaching. He rode on horse-back, with his retinue of clerks and monks, through his diocese, repeating the Psalter, the Litanies, and the office for the dead; his chamberlain always had a purse ready, and 'no one ever begged of Wulstan in vain.' In these progresses he came into personal contact with all his flock, high and low-with the rude crowds, beggars and serfs, craftsmen and labourers, as well as with priests and nobles. But everything gave way to his confirming children - from sunrise to sunset he would go without tasting food, blessing batch after hatch of the little ones. Wulstan was a great church builder: he took care that on each of his own manors there should be a church, and he urged other lords to follow his example. He rebuilt the cathedral of his see, and restored the old ruined church of Westbury. When his new cathedral was ready for use, the old one built by St. Oswald was to be demolished; Wulstan stood in the churchyard looking on sadly and silently, but at last burst into tears at this destruction, as he said, of the work of saints, who knew not how to build fine churches, but knew how to sacrifice themselves to God, whatever roof might be over them. Still, with a life of pastoral activity, Wulstan retained the devotional habits of the cloister. His first words on awaking were a psalm; and some homily or legend was read to him as he lay down to rest. He attended the same services as when in the monastery; and each of his manor houses had a little chapel, where he used to lock himself in to pray in spare hours. It cannot be said of Wulstan that he was much of a respecter of persons. He had rebuked and warned the headstrong Harold, and he was not less bold before his more imperious successor. At a council in Winchester, he bluntly called upon William to restore to the see some lands which he had seized. He had to fight a stouter battle with Lanfranc, who, ambitious of deposing him for incapacity and ignorance, in a synod held before the king, called upon the bishop to deliver up his pastoral staff and ring; when, according to the legend, Wulstan drove the staff into the stone of the tomb of the Confessor, where it remained fast imbedded, notwithstanding the efforts of the Bishop of Rochester, Lanfranc, and the king himself, to remove it, which, however, Wulstan easily did, and thenceforth was reconciled to Lanfranc; and they subsequently cooperated in destroying a slave trade which had long been carried on by merchants of Bristol with Ireland. Wulstan outlived William and Lanfranc. He passed his last Lent with more than usual solemnity, on his last Maundy washing the feet and clothes of the poor, bestowing alms and ministering the cup of 'charity;' then supplying them, as they sat at his table, with shoes and victuals; and finally reconciling penitents, and washing the feet of his brethren of the convent. On Easter-day, he again feasted with the poor. At Whitsuntide following, being taken ill, he prepared for death, but he lingered till the first day of the new year, when he finally took to his bed. He was laid so as to have a view of the altar of a chapel, and thus he followed the psalms which were sung. On the 19th of January 1095, at midnight, he died in the eighty-seventh year of his age, and the thirty-third of his episcopate. Contrary to the usual custom, the body was laid out, arranged in the episcopal vestments and crosier, before the high altar, that the people of Worcester might look once more on their good bishop. His stone coffin is, to this day, shewn in the presbytery of the cathedral, the crypt and early Norman portions of which are the work of Wnlstan. JAMES WATTJames Watt was, as is well known, a native of the then small seaport of Greenock, on the Firth of Clyde. His grandfather was a teacher of mathematics. His father was a builder and contractor-also a merchant,-a man of superior sagacity, if not ability, prudent and benevolent. The mother of Watt was noted as a woman of fine aspect, and excellent judgment and conduct. When boatswains of ships came to the father's shop for stores, he was in the habit of throwing in an extra quantity of sail-needles and twine, with the remark, 'See, take that too; I once lost a ship for want of such articles on board.' The young mechanician received a good elementary education at the schools of his native town. It was by the overpowering bent of his own mind that he entered life as a mathematical-instrumentmaker.  When he attempted to set up in that business at Glasgow, he met with an obstruction from the corporation of Hammermen, who looked upon him as an intruder upon their privileged ground. The world might have lost Watt and his inventions through this unworthy cause, if he had not had friends among the professors of the University,-Muirhead, a relation of his mother, and Anderson, the brother of one of his dearest school-friends,-by whose influence he was furnished with a workshop within the walls of the college, and invested with the title of its instrument-maker. Anderson, a man of an advanced and liberal mind, was Professor of Natural Philosophy, and had, amongst his class apparatus, a model of Newcomen's steam-engine. He required to have it repaired, and put it into Watt's hands for the purpose. Through this trivial accident it was that the young mechanician was led to 'make that improvement of the steam-engine which gave a new power to civilized man, and has revolutionised the world. The model of Newcomen has very fortunately been preserved, and is now in the Hunterian Museum at Glasgow College. Watt's career as a mechanician, in connection with Mr. Boulton, at the Soho Works, near Birmingham, was a brilliant one, and ended in raising him and his family to fortune. Yet it cannot be heard without pain, that a sixth or seventh part of his time was diverted from his proper pursuits, and devoted to mere ligitation, rendered unavoidable by the incessant invasions of his patents. He was often consulted about supposed inventions and discoveries, and his invariable rule was to recommend that a model should be formed and tried. This he considered as the only true test of the value of any novelty in mechanics. CONGREVE AND VOLTAIRECongreve died at his house in Surrey-street, Strand, from an internal injury received in being overturned in his chariot on a journey to Bath-after having been for several years afflicted with blindness and gout. Here he was visited by Voltaire, who had a great admiration of him as a writer. 'Congreve spoke of his works,' says Voltaire, 'as of trifles that were beneath him, and hinted to me, in our first conversation, that I should visit him on no other footing than upon that of a gentleman who led a life of plainness and simplicity. I answered, that, had he been so unfortunate as to be a mere gentleman, I should never have come to see him; and I was very much disgusted at so unreasonable a piece of vanity.' This is a fine rebuke. Congreve's remains lay in state in the Jerusalem Chamber, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey, where a monument was erected to his memory by Henrietta, Duchess of Marlborough, to whom he bequeathed £10,000, the accumulation of attentive parsimony. The Duchess purchased with £7,000 of the legacy a diamond necklace. 'How much better,' says Dr Young, 'it would have been to have given the money to Mrs. Brace-girdle, with whom Congreve was very intimate for years; yet still better would it have been to have left the money to his poor relations in want of it.' ISAAC DISRAELIFew miscellanies have approached the popularity enjoyed by the Curiosities of Literature, the work by which Mr. Disraeli is best known. This success may be traced to the circumstances of his life, as well as his natural abilities, favouring the production of exactly such a work. When a boy, he was sent to Amsterdam, and placed under a preceptor, who did not take the trouble to teach him anything, but turned him loose into a good library. Nothing could have been better suited to his taste, and before he was fifteen he had read the works of Voltaire and dipped into Bayle. When he was eighteen he returned to England, half mad with the sentimental philosophy of Rousseau. He declined to enter mercantile life, for which his father had intended him; he then went to Paris, and stayed there, chiefly living in the public libraries until a short time before the outbreak of the French Revolution. Shortly after his return to England he wrote a poem on the Abuse of Satire, levelled at Peter Pindar; it was successful, and made Disraeli's name known. In about two years, after the reading of Andrews's Anecdotes, Disraeli remarked that a very interesting miscellany might be drawn up by a well-read man from the library in which he lived. It was objected that such a work would be a mere compilation of dead matter, and uninteresting to the public. Disraeli thought otherwise, and set about preparing a volume from collections of the French Ana, the author adding as much as he was able from English literature. This volume he called Curiosities of Literature. Its great success induced him to publish a second volume; and after these volumes had reached a fifth edition, he added three more. He then suffered along illness, but his literary habits were never laid aside, and as often as he was able he worked in the morning in the British Museum, and in his own library at night. He published works of great historical research, including the Life and Reign of Claarles l in five volumes, and the Amenities of Literature in three volumes; but the great aim of his life was to write a History of English Literature, of which the Amenities were to be the materials. His literary career was cut short in 1839 by a paralysis of the optic nerve. He died at the age of eighty-two, retaining to the last, his sweetness and serenity of temper and cheerfulness of mind. Shortly before, his son wrote, for a new edition of the Curiosities of Literature, a memoir of the author, in which he thus happily sketched the features of his father's character: 'He was himself a complete literary character, a man who really passed his life in his library. Even marriage produced no change in these habits; he rose to enter the chamber where he lived alone with his books, and at night his lamp was ever lit within the same walls. Nothing, indeed, was more remarkable than the isolation of this prolonged existence; and it could only be accounted for by the united influences of three causes: his birth, which brought him no relations or family acquaintance; the bent of his disposition; and the circumstance of his inheriting an independent fortune, which rendered unnecessary those exertions that would have broken up his self-reliance. He disliked business, and he never required relaxation; he was absorbed in his pursuits. In London his only amusement was to ramble among booksellers; if he entered a club, it was only to go into the library. In the country, he scarcely ever left his room but to saunter in abstraction upon a terrace; muse over a chapter, or coin a sentence. He had not a single passion or prejudice; all his convictions were the result of his own studies, and were often opposed to the impressions which he had early imbibed. He not only never entered into the politics of the day, but he could never understand them. He never was connected with any particular body or set of men; comrades of school or college, or confederates in that public life which, in England, is, perhaps, the only foundation of real friendship. In the consideration of a question, his mind was quite undisturbed by traditionary preconceptions; and it was this exemption from passion and prejudice which, although his intelligence was naturally somewhat too ingenious and fanciful for the conduct of close argument, enabled him, in investigation, often to shew many of the highest attributes of the judicial mind, and particularly to sum up evidence with singular happiness and ability.' FAC-SIMILES OF INEDITED AUTOGRAPHS - ISABEL, QUEEN OF DENMARKDied at Ghent, of a broken heart, January 19, 1525, Isabel of Austria, Queen of Denmark, a 'nursing mother' of the Reformation. Isabel was the second daughter of Philip the Fair of Austria, and Juana la Loca, the first Queen of Spain. She was born at Brussels in 1501, and married at Malines, August 12, 1515, to Christiern of Denmark, who proved little less than her murderer. When he, 'the Nero of the North,' was deposed by his infuriated subjects, she followed him into exile, soothed him and nursed him, for which her only reward was cruel neglect, and, some add, more cruel treatment, descending even to blows. The frail body which shrined the bright, loving spirit, was soon worn out; and Isabel died, as above stated, aged only twenty-four years. It will be seen that the Queen spells her name Elizabeth, probably as more consonant with Danish ideas, for she was baptized after her grandmother, Isabel the Catholic. It is well known that our ancestors (mistakenly) considered here given is from the Cotton MSS. (Brit. Illus.) Elizabeth and Isabel identical. The autograph Vesp. F. III. SCARBOROUGH WARNINGToby Matthew, Bishop of Durham, in the postcript of a letter to the Archbishop of York, dated January 19, 1603, says: 'When I was in the midst of this discourse, I received a message from my Lord Chamberlain, that it was his Majesty's pleasure that I should preach before him on Sunday next; which Scarborough warning did not only perplex me, &c.' 'Scarborough warning' is alluded to in a ballad by Heywood, as referring to a summary mode of dealing with suspected thieves at that place; by Fuller, as taking its rise in a sudden surprise of Scarborough Castle by Thomas Stafford in 1557; and it is quoted in Harrington's old translation of Ariosto They took them to a fort, with such small treasure, As in to Scarborow warning they had leasure. There is considerable likelihood that the whole of these writers are mistaken on the subject. In the parish of Anwoth, in the stewartry of Kirkcudbright, there is a rivulet called Skyreburn, which usually appears as gentle and innocent as a child, being just sufficient to drive a mill; but from having its origin in a spacious bosom of the neighbouring hills, it is liable, on any ordinary fall of rain, to come down suddenly in prodigious volume and vehemence, carrying away hayricks, washings of clothes, or anything else that may be exposed on its banks. The abruptness of the danger has given rise to a proverbial expression, generally used throughout the south-west province of Scotland,-'Skyreburn warning'. It is easy to conceive that this local phrase, when heard south of the Tweed, would be mistaken for Scarborough, warning; in which case, it would be only too easy to imagine an origin for it connected with that Yorkshire watering place. Shakspeare's Geographical Knowledge.-The great dramatist's unfortunate slip in representing, in his Winters Tale, a shipwrecked party landing in Bohemia, has been palliated by the discovery which some one has made, that Bohemia, in the thirteenth century, had dependencies extending to the sea-coast. But the only real palliation of which the case is susceptible, lies in the history of the origin of the play. Our great bard, in this case, took his story from a novel named Pandosto. In doing so, for some reason which probably seemed to him good, he transposed the respective circumstances said to have taken place in Sicily and Bohemia, and, simply through advertence, failed to observe that what was suitable for an island like Sicily was unsuitable for an inland country like Bohemia. Shakespeare did not stand alone in his defective geographical knowledge. We learn from his contemporary, Lord Herbert of Cherbury, that Luines, the Prime Minister of France, when there was a question made about some business in Bohemia, asked whether it was an inland country, or lay upon the sea. We ought to remember that in the beginning of the seventeenth century, from the limited intercourse and interdependence of nations, there was much less occasion for geographical knowledge than there now is, and the means of obtaining it were also infinitely less. |