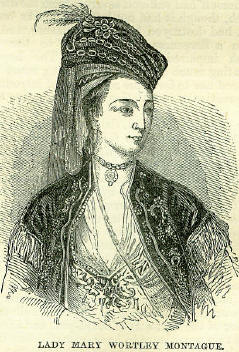

18th MarchBorn: Philip de Lahire, French geometrician, 1640, Paris; John Caldwell Calhoun, American statesman, 1782, South Carolina. Died: Edward, King and Martyr, 978; Pope Honorius III, 1227; Bishop Patrick Forbes, 1635, Aberdeen; Dr. George Stanhope, eminent divine, 1728, Lewisham; Sir Robert Walpole, (Earl of Orford,) prime minister to George I and II, 1745, Houghton; the Rev. Lawrence Sterne, author of Tristram Shandy, 1768, Bond street; John Horne Tooke, political writer, 1812, Ealing; Sebastian Pether, painter of moonlight scenery, 1844, Battersea; Sir Henry Pottinger, G.C.B., military commander in India, 1856; W. H. Playfair, architect, 1857,Edinburgh. Feast Day: St. Alexander, Bishop of Jerusalem, martyr, 251. St. Cyril, Archbishop of Jerusalem, 336. St. Fridian, Bishop of Lucca, 578. St. Edward, King of England, and martyr, 978. St. Anselm, Bishop of Lucca, 1086. EDWARD THE KING AND MARTYRThe great King Edgar had two wives, first Elfleda, and, after her death, Elfrida, an ambitious woman, who had become queen through the murder of her first husband, and who survived her second; and Edgar left a son by each, Edward by Elfleda, and Ethelred by Elfrida. At the time of their father's death, Edward was thirteen, and Ethelred seven years of age; and they were placed by the ambition of Elfrida, and by political events, in a position of rivalry. Edgar's reign had been one continued struggle to establish monarchism, and with it the supremacy of the Church of Rome, in Anglo-Saxon England; and the violence with which this design had been carried out, with the persecution to which the national clergy were subjected, now caused a reaction, so that at Edgar's death the country was divided into two powerful parties, of which the party opposed to the monks was numerically the strongest. The queen joined this party, in the hope of raising her son to the throne, and of ruling England in his name; and the feeling against the Romish usurpation was so great, that, although Edgar had declared his wish that his eldest son should succeed him, and his claim was no doubt just, the crown was only secured to him by the energetic interference of Dunstan. Edward thus became King of England in the year 975. Edward appears, as far as we can learn, to have been an amiable youth, and to have possessed some of the better qualities of his father; but his reign and life were destined to be cut short before he reached an age to display them. He had sought to conciliate the love of his step-mother by lavishing his favour upon her, and he made her a grant of Dorsetshire, but in vain; and she lived, apparently in a sort of sullen state, away from court, with her son Ethelred, at Corfe in that county, plotting, according to some authorities, with what may be called the national party, against Dunstan and the government. The Anglo-Saxons were all passionately attached to the pleasures of the chase, and one day-it was the 18th of March 978-King Edward was hunting in the forest of Dorset, and, knowing that he was in the neighbourhood of Corfe, and either suffering from thirst or led by the desire to see his half-brother Ethelred, for whom he cherished a boyish attachment, he left his followers and rode alone to pay a visit to his mother. Elfrida received him with the warmest demonstrations of affection, and, as he was unwilling to dismount from his horse, she offered him the cup with her own hand. While he was in the act of drinking, one of the queen's attendants, by her command, stabbed him with a dagger. The prince hastily turned his horse, and rode toward the wood, but he soon became faint and fell from his horse, and his foot becoming entangled in the stirrup, he was dragged along till the horse was stopped, and the corpse was carried into the solitary cottage of a poor woman, where it was found next morning, and, according to what appears to be the most trustworthy account, thrown by Elfrida's directions into an adjoining marsh. The young king was, however, subsequently buried at Wareham, and removed in the following year to be interred with royal honours at Shaftesbury. The monastic party, whose interests were identified with Edward's government, and who considered that he had been sacrificed to the hostility of their opponents, looked upon him as a martyr, and made him a saint. The writer of this part of the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, who was probably a contemporary, expresses his feelings in the simple and pathetic words, 'No worse deed than this was done to the Anglo race, since they first came to Britain.' The story of the assassination of King Edward is sometimes quoted in illustration of a practice which existed among the Anglo-Saxons. Our forefathers were great drinkers, and it was customary with them, in drinking parties, to pass round a large cup, from which each in turn drunk to some of the company. He who thus drank, stood up, and as he lifted the cup with both hands, his body was exposed without any defence to a blow, and the occasion was often seized by an enemy to murder him. To prevent this, the following plan was adopted. When one of the company stood up to drink, he required the companion who sat next to him, or some one of the party, to be his pledge, that is, to be responsible for protecting him against anybody who should attempt to take advantage of his defenceless position: and this companion, if he consented, stood up also, and raised his drawn sword in his hand to defend him while drinking. This practice, in an altered form, continued long after the condition of society had ceased to require it, and was the origin of the modern practice of pledging in drinking. At great festivals, in some of our college halls and city companies, the custom is preserved almost in its primitive form in passing round the ceremonial cup-the loving cup, as it is sometimes called. As each person rises and takes the cup in his hand to drink, the man seated next to him rises also, and when the latter takes the cup in his turn, the individual next to him does the same. LAWRENCE STERNEThe world is now fully aware of the moral deficiencies of the author of Tristram Shandy. Let us press lightly upon them for the sake of the bright things scattered through his writings -though these, as a whole, are no longer read. The greatest misfortune in the case is that Sterne was a clergyman. Here, however, we may charitably recall that he was one of the many who have been drawn into that profession, rather by connection than their own inclination. If Sterne had not been the great-grandson of an Archbishop of York, with an influential pluralist uncle, who could give him preferment, we should probably have been spared the additional pain of considering his improprieties as made the darker by the complexion of his coat. He spent the best part of his life as a life-enjoying, thoughtless, but not particularly objectionable country pastor, at Sutton in Yorkshire, and he had attained the mature age of forty-seven when the first volumes of his singular novel all at once brought him into the blaze of a London reputation. It was mainly during the remaining eight years of his life that he incurred the blame which now rests with his name. These years were made painful to him by wretched health. His constitution seems to have been utterly worn out. A month after the publication of his Sentimental Journey, while it was reaping the first fruits of its rich lease of fame, the poor author expired in solitary and melancholy circumstances, at his lodgings in Old Bond-street.  There is something peculiarly sad in the death of a merry man. One thinks of Yorick-' Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table in a roar?' We may well apply to Sterne-since he applied them to himself-the mournful words, 'Alas, poor Yorick! 'Dr. Dibdin found, in the possession of Mr. James Atkinson, an eminent medical practitioner at York, a very curious picture, done rather coarsely in oil, representing two figures in the characters of quack doctor and mountebank on a stage, with an indication of populace looking on. An inscription, to which Mr. Atkinson appears to have given entire credence, represented the doctor as Mr. T. Brydges, and the mountebank as Lawrence Sterne: and the tradition was that each had painted the other. It seems hardly conceivable that a parish priest of Yorkshire in the middle of the eighteenth century should have consented to be enduringly presented under the guise and character of a stage mountebank; but we must remember how much he was at all times the creature and the victim of whim and drollery, and how little control his profession and calling ever exercised over him. Mr. Atkinson, an octogenarian, told Dibdin that his father had been acquainted with Sterne, and he had thus acquired many anecdotes of the whims and crotchets of the far-famed sentimental traveller. Amongst other things which Dibdin fond of exercising his pencil. In our copy of the picture in question, albeit it is necessarily given learned here was the fact that Sterne possessed the talent of an amateur draughtsman, and was on a greatly reduced scale, it will readily be observed that the face of Sterne wears the characteristic comicality which might be expected BURNING OF TWO HERETICSOn Wednesday, the 18th of March 1611-12, one Bartholomew Legat was burnt at Smithfield, for maintaining thirteen heretical (Arian) opinions concerning the divinity of Christ. It was at the instance of the king, himself a keen controversialist, that the bishops, in consistory assembled, tried, and condemned this man. The lawyers doubted if there were any law for burning heretics, remarking that the executions for religion under Elizabeth were 'done de facto and not de jure.' Chamberlain, however, thought the King would 'adventure to burn Legat with a good conscience.' And adventure he did, as we see, taking self-sufficiency of opinion for conscience, as has been so often done before and since. Nor did he stop there, for on the 11th of April following, 'another miscreant heretic,' named William Wightman, was burnt at Lichfield. We learn that Legat declared his contempt for all ecclesiastical government, and refused all favour. He 'said little, but died obstinately.' King James had no mean powers as a polemic. He could argue down heretics and papists to the admiration (not wholly insincere) of his courtiers. It was scarcely fair that he should have had so powerful an ally as the executioner to close the argument. It is startling to observe the frequency of bloodshed in this reign for matters of opinion. As an example-on the Whitsun-eve of the year 1612, four Roman Catholic priests, who had previously been 'twice banished, but would take no warning' (such is the cool phrase of Chamberlain), were hanged at Tyburn. It is remarked, as a fault of some of the officials, that, being very confident at the gallows, they were allowed to 'talk their full' to the assembled crowd, amongst whom were several of the nobility, and others, both ladies and gentlemen, in coaches. THE OMNIBUS TWO HUNDRED YEARS AGOIt may appear strange, but the omnibus was known in France two centuries ago. Carriages on hire had already been long established in Paris: coaches, by the hour or by the day, were let out at the sign of St. Fiacre: but the hire was too expensive for the middle classes. In 1662, a royal decree of Louis XIV authorized the establishment of a line of twopence-halfpenny omnibuses, or carosses à cinq sous, by a company, with the Duke de Roanès and two marquises at its head, and the gentle Pascal among the shareholders. The decree expressly stated that these coaches, of which there were originally seven, each containing eight places, should run at fixed hours, full or empty, to and from certain extreme quarters of Paris, 'for the benefit of a great number of persons ill provided for, as persons engaged in lawsuits, infirm people, and others, who have not the means to ride in chaise or carriage, which cannot be hired under a pistole, or a couple of crowns a day.' The public inauguration of the new conveyances took place on the 18th of March 1662, at seven o'clock in the morning, and was a grand and gay affair. Three of the coaches started from the Porte St. Antoine, and four from the Luxembourg. Previous to their setting out, two commissaries of the Chatelet, in legal robes, four guards of the grand provost, half a score of city archers, and as many cavalry, drew up in front of the people. The commissaries delivered an address upon the advantages of the twopence-halfpenny carriages, exhorted the riders to observe good order, and then, turning to the coachmen, covered the body of each with a long blue frock, with the arms of the King and the city showily embroidered on the front. With this badge off drove the coachmen: but throughout the day, a provost-guard rode in each carriage, and infantry and cavalry, here and there, proceeded along the requisite lines, to keep them clear. There are two accounts of the reception of the novelty. Sanval, in his Antiquities of Paris, states the carriages to have been pursued with the stones and hisses of the populace, but the truth of this report is doubted: and the account given by Madame Perrier, the sister of the great Pascal, describing the public joy which she witnessed on the appearance of these low-priced conveyances, in a letter written three days after, is better entitled to credit: unless the two accounts may relate to the reception by the people in different parts of the line. For a while all Paris strove to ride in these omnibuses, and some stood impatiently to gaze at those who had succeeded better than themselves. The twopence-halfpenny coach was the event of the day: even the Grand Monarque tried a trip in one at St. Germains, and the actors of the Marais played the Intrigue des Carosses à Cinq Sous, in their joyous theatre. The wealthier classes seem to have taken possession of them for a considerable time; and it is singular that when they ceased to be fashionable, the poorer classes would have nothing to do with them, and so the speculation failed. The system reappeared in Paris in 1827, with this inscription placed upon the sides of the vehicles: Enterprise generate des Omnibus. In the Monthly Magazine for 1829, we read: 'The Omnibus is a long coach, carrying fifteen or eighteen people, all inside. Of these carriages, there were about half a dozen some months ago, and they have been augmented since: their profits are said to have repaid the outlay within the first year: the proprietors, among whom is Lafitte, the banker, are making a large revenue out of Parisian sous, and speculation is still alive.' The next item in the history of the omnibus is of a different cast. In the struggle of the Three Days of July 1830, the accidental upset of anomnibus suggested the employment of the whole class of vehicles for the forming of a barricade. The help thus given was important, and so it came to pass that this new kind of coach had some-thing to do in the banishing of an old dynasty. The omnibus was readily transplanted to London. Mr. Shillibeer, in his evidence before the Board of Health, stated that, on July 4, 1829, he started the first pair of omnibuses in the metropolis, from the Bank of England to the Yorkshire Stingo, New Road. Each of Shillibeer's vehicles carried twenty-two passengers inside, but only the driver outside; each omnibus was drawn by three horses abreast, the fare was one shilling for the whole journey, and sixpence for half the distance, and for some time the passengers were provided with periodicals to read on the way. The first conductors were two sons of British naval officers, who were succeeded by young men in velveteen liveries. The first omnibuses were called 'Shillibeers,' and the name is common to this day in New York. The omnibus was adopted in Amsterdam in 1839: and it has since been extended to all parts of the civilized world. INTRODUCTION OF INOCULATION March 18th 1718, Lady Mary Wortley Montague, at Belgrade, caused her infant son to be inoculated with the virus of small-pox, as a means of warding off the ordinary attack of that disease. As a preliminary to the introduction of the practice into England, the fact was one of importance: and great credit will always be due to this lady for the heroism which guided her on the occasion. At the time when Dr. Sydenham published the improved edition of his work on fevers, in 1675, small-pox appears to have been the most widely diffused and the most fatal of all the pestilential diseases, and was also the most frequently epidemic. The heating and sweating plan of treatment prevailed universally. Instead of a free current of air and cooling diet, the patient was kept in a room with closed windows and in a bed with closed curtains. Cordials and other stimulants were given, and the disease, assumed a character of malignity which increased the mortality to a frightful extent. The regimen which Dr. Sydenham recommended was directly the reverse, and was gradually assented to and adopted by most of the intelligent practitioners. Inoculation of the small-pox is traditionally reported to have been practised in some mode in China and Hindustan: and Dr. Russell, who resided for some years at Aleppo, states, as the result of his inquiries, that it had been in use among the Arabians from ancient times: but he remarks, that no mention is made of it by any of the Arabian medical writers known in Europe. (Phil. Trans. lviii. 142.) None of the travellers in Turkey have noticed the practice previous to the eighteenth century. The first accounts are by Pylarini and Timoni, two Italian physicians, who, in the early part of the eighteenth century, sent information of the practice to the English medical professors, by whom, however, no notice was taken of it. It was in the course of her residence in Turkey, with her husband Mr. Edward Wortley Montague, the British ambassador there, that Lady Mary made her famous experiment in inoculation. Her own experience of small-pox had led her, as she acknowledged, to observe the Turkish practice of inoculation with peculiar interest. Her only brother, Lord Kingston, when under age, but already a husband and a father, had been carried off by small-pox: and she herself had suffered severely from the disease, which, though it had not left any marks on her face, had destroyed her fine eyelashes, and had given a fierceness of expression to her eyes which impaired their beauty. The hope of obviating much suffering and saving many lives induced her to form the resolution of introducing the practice of inoculation into her native country. In one of her letters, dated Adrianople, April 1st, 1717, she gives the following account of the observations which she had made on the proceedings of the Turkish female practitioners: The small-pox, so general and so fatal amongst us, is entirely harmless by the invention of in-grafting, which is the term they give it. There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated. People send to one another to know if any one has a mind to have the small-pox. They make parties for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly fifteen or sixteen together), the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks you what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch), and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle, and after that binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell, and in this manner opens four or five veins The children or young patients play together all the rest of the day, and are in perfect health till the eighth. Then the fever begins to seize them, and they keep their beds two days, very seldom three. They have very rarely above twenty or thirty on their faces, which never mark, and in eight days' time they are as well as they were before their illness. Where they are wounded there remain running sores during the distemper, which, I don't doubt, is a great relief to it. Every year thousands undergo the operation: and the French ambassador says pleasantly that they take the small-pox here by way of diversion, as they take the waters in other countries. There is no example of any one that has died of it: and you may believe me that I am well satisfied of the safety of this experiment, since I intend to try it upon my dear little son. I am patriot enough to try to bring this useful invention into fashion in England. While her husband, for the convenience of attending to his diplomatic duties, resided at Pera, Lady Mary occupied a house at Belgrade, a beautiful village surrounded by woods, about fourteen miles from Constantinople, and there she carried out her intention of having her son inoculated. On Sunday, the 23rd of March 1718, a note addressed to her husband at Pera contained the following passage: The boy was ingrafted on Tuesday, and is at this time singing and playing, very impatient for his supper. I pray God my next may give you as good an account of him. I cannot ingraft the girl: her nurse has not had the small-pox. Lady Mary Wortley Montague, after her return from the East, effectively, though gradually and slowly, accomplished her benevolent intention of rendering the malignant disease as comparatively harmless in her own country as she had found it to be in Turkey. It was an arduous, a difficult, and, for some years, a thankless under-taking. She had to encounter the pertinacious opposition of the medical professors, who rose against her almost to a man, predicting the most disastrous consequences: but, supported firmly by the Princess of Wales (afterwards Queen Caroline) she gained many supporters among the nobility and the middle classes. In 1721 she had her own daughter inoculated. Four chief physicians were deputed by the government to watch the performance of the operation, which was quite successful: but the doctors were apparently so desirous that it should not succeed, that she never allowed the child to be alone with them for a single instant, lest it should in some way suffer from their malignant interference. Afterwards four condemned criminals were inoculated, and this test having proved successful, the Princess of Wales had two of her own daughters subjected to the operation with perfect safety. While the young princesses were recovering, a pamphlet was published which denounced the new practice as unlawful, as an audacious act of presumption, and as forbidden in Scripture by the express command: 'Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.' Some of the nobility followed the example of the Princess, and the practice gradually extended among the middle classes. The fees at first were so expensive as to preclude the lower classes from the benefit of the new discovery. Besides the opposition of the medical professors, the clergy denounced the innovation from their pulpits as an impious attempt to take the issues of life and death out of the hands of Providence. For instance, on the 8th of July 1722, a sermon was preached at St. Andrew's, Holborn, in London, by the Rev. Edward Massey, Lecturer of St. Alban's, Wood-street, 'against the dangerous and sinful practice of inoculation.' The sermon was published, and the text is Job ii. 7: So went Satan forth from the presence of the Lord, and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of his foot unto his crown.' The preacher says: 'Remembering our text, I shall not scruple to call that a diabolical operation which usurps an authority founded neither in the laws of nature or religion; which tends, in this case, to anticipate and banish Providence out of the world, and promote the increase of vice and immorality. The preacher further observes that 'the good of mankind, the seeking whereof is one of the fundamental laws of nature, is, I know, pleaded in defence of the practice; but I am at a loss to find or understand how that has been or can be promoted hereby; for if by good be meant the preservation of life, it is, in the first place, a consideration whether life be a good or not.' In addition to denunciations such as these from high places, the common people were taught to regard Lady Mary with abhorrence, and to hoot at her, as an unnatural mother who had risked the lives of her own children. So annoying was the opposition and the obloquy which Lady Mary had to endure, that she confessed that, during the four or five years which immediately succeeded her return to England, she often felt a disposition to regret having engaged in the patriotic undertaking, and declared that if she had foreseen the vexation and persecution which it brought upon her she would never have attempted it. In fact, these annoyances seem at one time to have produced a depression of spirits little short of morbid; for in 1725 she wrote to her sister Lady Mar: I have such a complication of things both in my head and my heart, that I do not very well know what I do; and if I cannot settle my brains, your next news of me will be that I am locked up by my relations. In the meantime I lock myself up, and keep my distraction as private as possible. It is remarkable that Voltaire should have been the first writer in France to recommend the adoption of inoculation to the inhabitants of that country. In 1727 he directed the attention of the public to the subject. He pointed out to the ladies especially the value of the practice, by informing them that the females of Circassia and Georgia had by this means preserved the beauty for which they have for centuries been distinguished. He stated that they inoculated their children at as early an age as six months; and observed that most of the 20,000 inhabitants of Paris who died of small-pox in 1720 would probably have been saved if inoculation had been then in use. Dr. Gregory has observed, that the first ten years of the progress of inoculation in England were singularly unfortunate. It fell into bad hands, was tried on the most unsuitable subjects, and was practised in the most injudicious manner. By degrees the regular practitioners began to patronise and adopt it, the opposition of the clergy ceased, and the public became convinced of the fact that the disease in the new form was scarcely ever fatal, while they were aware from experience that when it occurred naturally, one person died out of about every four. A new era in the progress of inoculation commenced when the Small-pox Hospital was founded by voluntary subscription in 1746, for the extension of the practice among the poor of London. Dr. Mead, who had been present when the four criminals were inoculated, wrote a treatise in favour of it in 1748, and the College of Physicians published a strong recommendation of it in 1754. Mr. Sutton and his two sons, from about 1763, became exceedingly popular as inoculators; in 1775 a dispensary was opened in London for gratuitous inoculation of the poor, and Mr. Dimsdale at the same time practised with extraordinary success. The Small-pox Hospital having adopted the plan of promiscuous inoculation of out-patients, carried it on to an immense extent between 1790 and 1800. In 1796, Dr. Jenner announced his discovery of vaccination, and inoculation of the small-pox was gradually superseded by inoculation of the cow-pox. On the 23rd of July 1840, the practice of inoculation of the small-pox was prohibited by an act of the British Parliament, 3 and 4 Viet. c. 29. This statute, entitled 'An Act to Extend the Practice of Vaccination,' enacted that any person who shall produce or attempt to produce by inoculation of variolous matter the disease of small-pox, shall be liable on conviction to be imprisoned in the common goal or house of correction for any term not exceeding one month.' |