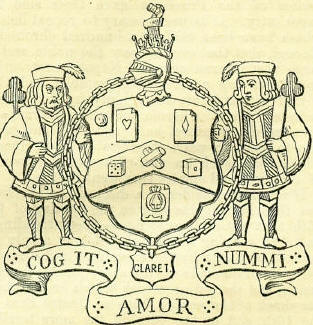

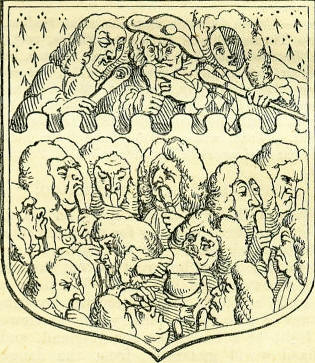

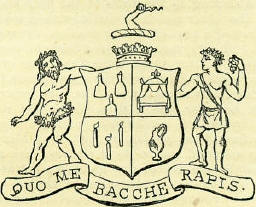

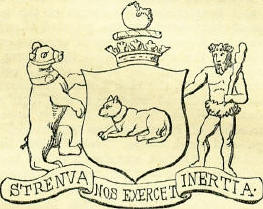

18th JuneBorn: Robert Stewart, Marquis of Londonderry, minister of George IV, 1769, London; Karl Wenceslaus Rodecker von Rotteck, historian, 1775, Frieburg, in Breisgau. Died: Caliph Othman, assassinated at Medina, 655; Bishop Thomas Bilson, 1616; A. Philips, poet, 1749, near Vauxhall, London; Gerard Van Swieten, eminent physician and teacher of medicine, 1772, Schoenbrunn, Vienna; Arthur Murphy, dramatist, 1805, Knightsbridge; General Sir Thomas Picton, 1815, Waterloo; William Coombe, novelist and comic poet, 1823, London; William Cobbett, political writer, 1835; John Roby, author of Traditions of Lancashire, drowned at sea off Portpatrick, 1850. Feast Day: Saints Marcus and Marcellianus, martyrs, 286; St. Amand, Bishop of Bordeaux; St. Marina, of Bithynia, virgin, 8th century; St. Elizabeth, of Sconauge, virgin and abbess, 1165. THE BATTLE OF WATERLOOWhen William IV was lying on his death-bed at Windsor, the firing for the anniversary of Waterloo took place, and on his inquiring and learning the cause, he breathed out faintly, 'It was a great day for England.' We may say it was so, in no spirit of vainglorious boasting on account of a well-won victory, but as viewed in the light of a liberation for England, and the civilized world generally, from the dangerous ambition of an unscrupulous and too powerful adversary. When Napoleon recovered his throne at Paris, in March 1815, he could only wring from an exhausted and but partially loyal country about two hundred thousand men to oppose to nearly a million of troops which the allied sovereigns were ready to muster against him. His first business was to sustain the attack of the united British and Prussians, posted in the Netherlands, and it was his obvious policy to make an attack on these himself before any others could come up to their assistance. His rapid advance at the beginning of June, before the English and Prussian commanders were aware of his having left Paris; his quick and brilliant assaults on the separate bodies of Prussians and British at Ligny and Quatre Bras on the 16th, were movements marked by all his brilliant military genius. And even when, on the 18th, he commenced the greater battle of Waterloo with both, the advantage still remained to him in the divided positions of his double enemy, giving him the power of bringing his whole host concentratedly upon one of theirs; thus neutralizing to some extent their largely superior forces. And, beyond a doubt, through the superior skill and daring which he thus shewed, as well as the wonderful gallantry of his soldiery, the victory at Waterloo ought to have been his. There was just one obstacle, and it was decisive-the British infantry stood in their squares immovable upon the plain till the afternoon, when the arrival of the Prussians gave their side the superiority. It is unnecessary to repeat details which have been told in a hundred chronicles. Enough that that evening saw the noble and in large part veteran army of Napoleon retreating and dispersing never to re-assemble, and that within a month his sovereignty in France had definitely closed. A heroic, but essentially rash. and ill-omened adventure, had ended in consigning him to those six years of miserable imprisonment which form such an anti-climax to the twenty of conquest and empire that went before. If we must consider it a discredit to Wellington that he was unaware on the evening of the 15th that action was so near-even attending a ball that evening in Brussels-it was amply redeemed by the marvellous coolness and sagacity with which he made all his subsequent arrangements, and the patience with which he sustained the shock of the enemy, both at Quatre Bras on the 16th, and on the 18th in the more terrible fight of Waterloo. Thrown on that occasion into the central position among the opponents of Bonaparte, he was naturally and justly hailed as the saviour of Europe, though at the same time nothing can be more clear than the important part which the equal force of Prussians bore in meeting the French battalions. Thenceforth the name of Wellington was venerated above that of any living Englishman. According to Alison, the battle of Waterloo was fought by 80,000 French and 250 guns, against 67,000 English, Hanoverians, Belgians, &c., with 156 guns, to which were subsequently added certain large bodies of Prussians, who came in time to assist in gaining the day. There were strictly but 22,000 British troops on the field, of whom the total number killed was 1417, and wounded 4923. The total loss of the allied forces on that bloody day was 22,378, of whom there were killed 4172. It was considered for that time a very sanguinary conflict, but The glory ends not, and the pain is past. BURLESQUE AND SATIRICAL HERALDRYHorace Walpole and a select few of his friends once beguiled the tedium of a dull day at Strawberry Hill by concocting a satirical coat-of-arms for a club in St. James's Street, which at that time had an unfortunate character for high play as well as deep drinking. The club was known as 'the Old and Young Club,' and met at Arthur's. Lady Hervey gives a clue to the peculiarity of its designation in a letter dated 1756, in which she laments that 'luxury increases, all public places are full, and Arthur's is the resort of old and young, courtiers and anti-courtiers-nay, even of ministers.' The arms were invented in 1756 by Walpole, Williams, George Selwyn, and the Honourable Richard Edgecumbe, and drawn by the latter. This drawing formed lot twelve of the twenty-second day's sale at Strawberry Hill in 1842, and is here engraved, we believe, for the first time.  The arms may be thus described:-On a green field (in allusion to the baize on a card table) three cards (aces); between, a chevron sable (for a hazard table), two rouleaus of guineas in saltier, and a pair of dice; on a canton, sable, a white election-ball. The crest is an arm issuing from an earl's coronet, and shaking a dice-box. The arms are surrounded by a claret-bottle ticket and its chain; the supporters are an old and a young Knave of Clubs; and the motto, 'Cogit amor nummi,' involves a pun in the first word, the letters being so separated as to allude to the cogging of dice for dishonest play. Burlesque heraldry very probably had its origin in the mock tournaments, got up in broad caricature by the Hanse Towns of Germany in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the real tournaments had lost their chivalric charm, and feudalism was fast fading away. The wealthy bourgeoisie of the great commercial towns delighted in holding these mock encounters, and parodied in every particular the tourneys and jousts of the old noblesse; dressing their combatants in the most grotesque fashion, with tubs for breastplates and buckets for helmets, and furnishing them with squires who bore their shields with coat-armour of absurd significance. In that curious old poem, The Tournament of Tottenham, preserved in Percy's Reliques, the plebeians who fight for Tyb the Reve's daughter proclaim their blazonry in accordance with their calling; one bears: A riddle and a rake, Powdered with a burning drake, And three cantells of a cake In each corner. Another combatant declares: In my arms I bear well, A dough trough and a peel, A saddle without a panel, With a fleece of wool. Severe satirical allusions to individuals were sometimes indulged in; the most celebrated being the coat-of-arms invented by Roy, and placed in the title-page of his bold and bitter attack on Wolsey; a satire in which Roy risked his life. It is printed in red and black, and described in caustic verse, of which we quote only as much as will explain it: Of the proud cardinal this is the shield, Borne up between two angels of Satan: The six bloody axes in a bare field Sheweth the cruelty of the red man. The six bulls' heads in a field black Betokeneth his sturdy furiousness. The bandog in the midst cloth express The mastiff cur bred in Ipswich town, Gnawing with his teeth a king's crown. The club signifieth plain his tyranny Covered over with a cardinal's hat.  Walpole, with his antiquarian tastes, must have been fully aware of these old satires; but he had a nearer and cleverer example in 'The Under-takers' Arms,' designed and published by Hogarth as a satire on medical quacks, whom he considers their best friends, and thus describes the coat: The Company of Undertakers beareth, sable, an urinal proper, between twelve quack heads of the second, and twelve cane heads, or, consultant. On a chief, nebuly, ermine, one complete doctor, issuant, cheeky, sustaining in his right band a baton of the second. On the dexter and sinister sides, two demi-doctors, issuant of the second, and two cane-heads issuant of the third; the first having one eye couchant, towards the dexter side of the escutcheon; the second faced, per pale, proper, and gules guardant. With this motto, Et plurima mortis imago (the general image of death).' The humour of this satire is by no means restricted to the whimsical adaptation of heraldic terms to the design, in which there is more than meets the eye, or will be understood without a Parthian glance at the quacks of Hogarth's era, and whom the artist hated with his usual sturdy dislike of humbug. Thus the coarse-faced central figure of the upper triad, arrayed in a harlequin jacket, is intended for one Mrs. Mapp, an Amazonian quack-doctress, who gained both fame and money as a bonesetter-her strength of arm being only equalled by her strength of language; there are some records of her sayings extant that are perfectly unquotable in the present day, yet she was called in by eminent physicians, and to the assistance of eminent people. To the right of this Amazon is the famous Chevalier Taylor, the oculist (indicated by the eye in the head of his cane), whose impudence was unparalleled, and whose memoirs, written by himself, if possible outdo even that in effrontery. To the lady's left is Dr. Ward, whose pills and nostrums gulled a foolish public to his own emolument. Ward was marked with what old wives call 'a claret stain' on his left cheek; and here heraldry is made of humorous use in depicting his face, per pale, gules. In 1785 a curious duodecimo volume was published, called The Heraldry of Nature; or, instructions for the .King-at-Arms: comprising the arms, supporting crests and mottoes of the Peers of England. Blazoned from the authority of Truth, and characteristically descriptive of the several qualities that distinguish their possessors. The author explains his position in a preface, where he states that he has 'rejected the common and patented bearings already painted on the carriages of our nobility, and instituted what he judges a wiser delineation of the honours they deserve.' He flies at the highest game, and begins with King George the Third himself, whose coat he thus describes: First, argent, a cradle proper; second, gules, a rod and sceptre, transverse ways; third, azure, five cups and balls proper; fourth, gules, the sun eclipsed proper; fifth, argent, a stag's head between three jockey caps; sixth, or, a house in ruins. Supporters: the dexter, Solomon treading on his crown; the sinister, a jackass proper. Crest: Britannia in despair. Motto: ' Neque tangunt levia' (little things don't move me).  The irregularities of the Prince of Wales are severely alluded to in his shield of arms, but the satire is too broad for modern quotation. The whole of the nobility are similarly provided with coats indicative of their characters. Two are here selected as good specimens of the whole. The first is that of the Duke of Norfolk, whose indolence, habit of late hours, and deep drinking were notorious; at public dinners he would drink himself into a state of insensibility, and then his servants would lift him in a chair to his bedroom, and take that opportunity of washing him; for his repugnance to soap and water was equal to his love of wine. The arms are 'quarterly; or, three quart bottles, azure; sable, a tent bed argent; azure, three tapers proper; and gules, a broken flagon of the first.  Supporters: dexter, a Silenus tottering; sinister, a grape-squeezer; both proper. Crest: a naked arm holding a corkscrew. Motto: ' Quo me, Bacche, rapis' (Bacchus, where are you running with me?).' For Seymour Duke of Somerset a simpler but not more complimentary coat is invented:-' Vert, a mastiff couchant, spotted proper. Sup-porters: dexter, a bear muzzled argent; sinister, a savage proper. Crest: a Wiltshire cheese, decayed. Motto: 'Strenua nos exercet inertia' (The laziest dog that ever lounged).'  Though most of the nobility are 'tarred with the same brush,' a few receive very complimentary coat-armour. Thus the Duke of Buccleuch bears 'azure a palm-tree, or Supporters: the dexter, Mercy; the sinister, Fortitude. Crest: the good Samaritan. Motto: 'Humani nihil alienum ' (I'm a true philanthropist).' The foppish St. John has his arms borne by two beaux, a box of lipsalve for a crest, and as a motto 'Felix, qui placuit.' Hone, whose erudition in parody was sufficient to save him in three separate trials for alleged profanity by the proven plea of past usages, invented for one of his satirical works a clever burlesque of the national arms of England; the shield being emblazoned in a lottery wheel, the animals were represented in the last stage of starvation, and all firmly muzzled. The shield is supported by a lancer (depicted as a centaur), who keeps the crown in its place with his lance. The other supporter is a lawyer (the Attorney-General, with an ex-officio information in his bag), whose rampant condition is expressed with so much grotesque humour, that we end our selection with a copy of this figure. THE BRITISH SOLDIER IN TROUSERSOn the 18th of June 1823, the British infantry soldier first appeared in trousers, in lieu of other nether garments. The changes in military costume had been very gradual, marking the slowness with which novelties are sanctioned at head-quarters. When the regiments of the line first began to be formed, about two centuries ago, the dress of the officers and men partook somewhat of the general character of civil costume in the reign of Charles II. We have now before us a series of coloured engravings, showing the chief changes in uniform from that time to the beginning of the present century. Under the year 1685, the 11th foot are represented in full breeches, coloured stockings, and high shoes. Under date 1688, the 7th and 5th foot appear in green breeches of somewhat less amplitude, white stockings, and high shoes. Under 1692, the 1st royals and the 10th foot are shewn in red breeches and stockings; while another regiment appears in high boots coming up over blue breeches. In 1742, various regiments appear in purple, blue, and red breeches, white leggings or gaiters up to the thigh, and a purple garter under the knee. This dress is shewn very frequently in Hogarth's pictures. In 1759, the foot-soldiers shewn in the 'Death of General Wolfe' have a sort of knee-cap covering the breeches and gaiters. In 1793, the 87th foot are represented in tight green pantaloons and Hessian boots. During the great wars in the early part of the present century, pantaloons were sometimes worn, breeches at others, but gaiters or leggings in almost every instance. The reform which took place in 1823 was announced in a Horse Guards' order, when the Duke of York was commander-in-chief. The order stated that 'His Majesty has been pleased to approve of the discontinuance of breeches, leggings, and shoes, as part of the clothing of the infantry soldiers; and of blue grey cloth trousers and half-boots being substituted.' After adverting to the deposit of patterns and the issue of supplies, the order makes provision for the very curious anomaly that used to mark the clothing system of the British army. 'In order to indemnify the colonels for the additional expense they will in consequence incur, the waistcoat hitherto provided with the clothing will be considered as an article of necessaries to be provided by the soldier; who, being relieved from the long and short gaiters, and also from the stoppage hitherto made in aid of the extra expense of the trousers (in all cases where such have been allowed to be furnished as part of the clothing of regiments), and being moreover supplied with articles of a description calculated to last longer than the breeches and shoes now used, cannot fail to be benefited by the above arrangement.' Non-professional readers may well be puzzled by the complexity of this announcement. The truth is, that until Lord Herbert of Lea (better known as Mr. Sidney Herbert) became Secretary of State for War, a double deception was practised on the rank and file of the British army, little creditable to the nation. The legislature voted annually, for the clothing of the troops, a sum much larger than was actually applied to that purpose; and the same legislature, by a similarly animal vote, gave about a shilling a day to each private soldier as pay, the greater part of which was anything but pay to him. In the first place, the colonel of each regiment had an annual allowance for clothing his men, with a well-understood agreement that he was to be permitted to purchase the clothing at a much lower rate, and put the balance in his own pocket. This balance usually varied from £600 to £1000 per annum, and was one of the prizes that made the 'clothing colonels' of regiments so much envied by their less fortunate brother-officers. In the second place, although the soldiers received their shilling a day, or thereabouts, as pay, so many deductions were made for the minor articles of sustenance and clothing, that only about fourpence remained at the actual disposal of each man. The two anomalies are brought into conjunction in a singular way in the above-quoted order, in reference to the soldier's waist-coat; the colonel was to be relieved from buying that said garment, and the poor soldier was to add the waistcoat to the number of 'necessaries' which he was to provide out of his slender pay. The miseries attendant on the Crimean war, by awaking public attention to the condition of the soldiers, led to the abandonment of the 'clothing colonel' system. |