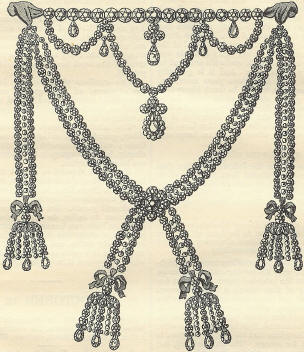

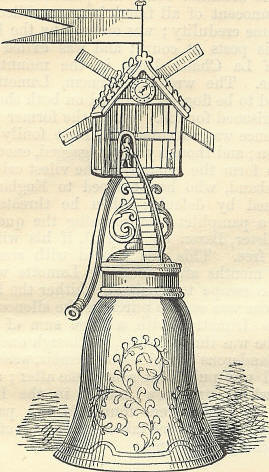

16th OctoberBorn: Dr. Albert Von Haller, distinguished physiologist, 1708, Berne; John George Sulzer, writer on the fine arts, 1720, Winterthur, in Zurich. Died: Bishops Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, martyred at Oxford, 1555; Roger Boyle, Earl of Orrery, politician and versifier, 1679; Robert Fergusson, Scottish poet, 1774, Edinburgh; Marie Antoinette, queen of Louis XVI, guillotined at Paris, 1793; John Hunter, celebrated anatomist, 1793, London; Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia, 1796; Joseph Strutt, antiquary, 1802, London; Sharman Crawford, Irish political character, 1861; Henry Martyn, oriental missionary, 1812, Tokcat, Asia Minor; Thaddeus Kosciusko, Polish patriot, 1817, Soleure, in Switzerland. Feast Day: St. Gall, abbot, 646. St. Mummolin or Mommolin, bishop of Noyon, confessor, 7th century. St. Lullus or Lullon, archbishop of Mentz, confessor, 787. STORY OF THE DIAMOND NECKLACEIn connection with the unfortunate Marie Antoinette, whose judicial murder by sentence of the Convention took place on 16th October 1793, we may in this place not inappositely introduce the famous story of the Diamond Necklace, in which the French queen played a conspicuous though involuntary part. This extraordinary affair originated in the profligate state of French society preceding the Revolution, when the upper classes, as if in mockery of the sufferings of the starving poor, displayed a magnificence as insulting as it was reckless and insane. We are told that the officers of the king's maisom militaire not only wore uniforms, but had the harness and caparisons of their horses covered with gold, and the very manes and tails of these animals plaited with gold braid. Louis XVI and his queen fell into this strange infatuation; and one of their most serious errors of judgment, was their conduct in the case of the Diamond Necklace, which cast a slur upon the fair fame of the queen, and finally proved one of the most deadly weapons in the hands of her enemies. The details long occupied the attention of the court of France, the College of Cardinals, and the higher ranks of the clergy. Many versions of the facts were given, but the following narrative, compiled from the documents of the case, from the memoirs, pamphlets, and petitions of the accusers and the accused, may be relied on as essentially correct. In 1774, Louis XV, wishing to make a present to his mistress, Madame du Barry, commissioned the court jewelers to collect the finest diamonds to form a necklace that should be unique of its kind. Some time and a considerable outlay were required to make arrangements to procure the largest, purest, and most brilliant diamonds. Unfortunately, before the necklace was completed, Louis XV was laid in his grave, and the fallen favorite was fain to be content with the riches she possessed, without requiring the execution of the deceased monarch's intentions. The work, however, was too far advanced to permit of its being abandoned without great loss; and in the hope that Louis XVI might be induced to purchase it for the queen, the jewelers finished the necklace, which was valued at 1,800,000 francs (£72,000 sterling). The new king's finances were in too low a state for him to purchase the necklace; and when it was offered to him, he replied that a ship was more needed than a necklace, which, therefore, remained in the hands of the jewelers for some years, until the occurrence of the event which, by breaking it up and dispersing it, gave it historical celebrity.  To understand by what a complication of circumstances, a woman without position, fortune, favor at court, or even very great charms of person, could have conceived the idea of obtaining an ornament that was beyond the means of sovereigns, can only be explained by reference to events much anterior to her meeting with her victim, and which gave rise to the life-long antipathy of Marie Antoinette to Louis, prince cardinal of Rohan. In 1772, the prince was appointed ambassador to Vienna. At one of the merry suppers of Louis XV, Madame du Barry drew from her pocket, and read aloud a letter, purporting to be addressed to her by the ambassador at Vienna, and giving particulars of the private life of the empress of Austria, whose daughter, Marie Antoinette, had been, three years previously, married to the dauphin. The prince was, however, guiltless of any thought of offending the dauphiness; he had had no correspondence with Madame du Barry, but had merely replied to the king's inquiries as to what was taking place at the imperial court. Louis had left one of the ambassador's private letters in the hands of the Duke d'Aguillon, who was a creature of Du Barry, and had given the letter to her, which she, with her accustomed levity, read to amuse her guests. The anger of Marie Antoinette, thus unwittingly incurred by M. de Rohan, continued to rankle in her breast after she had succeeded to the throne. Although, being allied to the most powerful families of France, and possessed of a princely income, he had obtained the post of grand-almoner of France, a cardinal's hat, the rich abbey of St. Waast, and had been elected proviseur of the Sorbonne, the displeasure of the queen effectually disgraced him at court, and embittered his very existence. Such was his disagreeable position when he was introduced to an intrigante, who, taking advantage of his desire to regain the royal favor, involved him in the disgraceful transaction that placed him before the world in the attitude of a thief and a forger. This woman was the descendant of royal blood, and had married a gendarme named Lamotte. Being reduced to beggary, she presented herself before the Cardinal de Rohan, to petition that in his capacity as grand-almoner, he would procure her aid from the royal bounty. Madame Lamotte, without being beautiful, had an intelligent and pleasing countenance and winning manners, and moved the cardinal prince to advance her sums of money. He then advised her to apply in person to the queen, and, lamenting it was not in his power to procure her an interview, was weak enough to betray the deep chagrin which the sovereign's displeasure had caused him. Some days after, Madame Lamotte returned, stating that she had obtained admittance to the queen's presence, had been questioned kindly, had introduced the name of the cardinal as being one of her benefactors, and, perceiving she was listened to with interest, had ventured to mention the grief he endured, and had obtained permission to lay before her majesty his vindication. This service Madame Lamotte tendered in gratitude to the prince, who intrusted to her the apology, written by himself, which she stated had been placed in the sovereign's hands, and to which a note was vouchsafed in reply, Madame Lamotte having previously ascertained that the cardinal had not seen, or did not remember, the queen's handwriting. The contents were as follows: I have seen your note; I am delighted to find you innocent. I cannot yet grant you the audience you solicit; as soon as circumstances will permit, I will let you know. Be discreet. The prince was now completely duped. He was convinced that Madame Lamotte was admitted daily into her majesty's private apartments, and he thought it natural that the lively queen should be amused by her quick witted sallies, and that she should make use of her as a ready tool. Following his guide's advice, he expressed his joy and gratitude in writing, and the correspondence thus commenced was continued, and so worded on the queen's part, that the cardinal had reason to believe that he had inspired unlimited confidence. When he was supposed to be sufficiently prepared, a note was risked from the queen, commissioning the grandalmoner to borrow for a charitable purpose 60,000 francs, and transmit them to her through the medium of Madame Lamotte. Absurd as was this clandestine negotiation, the cardinal believed it; he borrowed the money himself, and remitted it to Madame Lamotte, who brought, in return, a note of thanks. A second loan of a like amount was obtained. With these funds Madame Lamotte and her husband furnished. a house handsomely, and started gay equipages, though not until the artful woman had, through her usual medium a letter from the queen insinuated to the cardinal that, to prevent suspicion, he should absent himself for a time, when he instantly set out for Alsace. Meanwhile, Madame Lamotte accounted for her sudden opulence by saying that the queen's kindness supplied her with the means. Her majesty would not allow a descendant of royal blood to remain in poverty. This success emboldened Madame Lamotte to aim at much higher game. The court jewelers were by this time tired of having the costly necklace lying idle; an emissary of Madame Lamotte had insinuated to them, that an influential lady at court might be able to recommend the purchase of the necklace. A handsome present was promised for such a service. But Madame Lamotte was cautious; she did not meddle with such matters; she would consider the subject. In a few days, she called on the jewelers, and announced that a great lord would that morning look at the necklace, which he was commissioned to purchase. The cardinal, in the meantime, received from his quasi royal correspondent a note to hasten his return for a negotiation. On reaching Paris, he was informed that the queen earnestly desired to purchase the necklace without the king's knowledge, for which she would pay with money saved from her income. She had chosen the grand-almoner to negotiate the purchase in her name, as a special token of her favour and confidence. He was to receive an authorization, written and signed by the queen, though the contract was to be made in the cardinal prince's name. He unsuspectingly hastened to fulfill his mission; and on February 1, 1785, the necklace was placed in the cardinal's hands. Twenty thousand livres of the original price were taken off, quarterly payments agreed to, and the prince's note accepted for the whole amount. The jewelers, however, were made aware that the necklace was being purchased on her majesty's account, the prince having shewn them his authority, and charged them to keep the affair secret from all except the queen. The necklace was to be delivered on the eve of a great fLte, at which Madame Lamotte asserted the queen desired to wear it. The casket containing it was taken to Versailles, to the house of Madame Lamotte, by whom it was to be handed to the person whom the queen was to send. At dusk, the cardinal arrived, followed by his valet bearing the casket; he took it from the servant at the door, and, sending him away, entered alone. He was placed by Madame Lamotte in a closet opening into a dimly lighted apartment. In a few minutes a door was opened, a 'messenger from the queen' was announced, and a man entered. Madame Lamotte advanced, and respectfully placed the casket in the hands of the last comer, who retired instantly. And so adroitly was the deception managed, that the cardinal protested that through the glazed sash of the closet door, he had perfectly recognized the confidential valet of the queen! To strengthen the cardinal's belief, Madame Lamotte told him that she had taken lodgings at Versailles, as the queen was desirous of having her at hand; and to corroborate this statement, she persuaded the cardinal, disguised, to accompany her, when the queen, as she pretended, desired her attendance at Trianon. On one of these occasions, Madame Lamotte and the cardinal were escorted by the pretended valet, who was the former's accomplice; but it was the concierge of the Chateau of Trianon, and not the queen, whom Madame Lamotte went to visit. The acknowledgment of the necklace was next artfully planned. Madame Lamotte had noticed that when the queen passed from her own apartment, crossing the gallery, to go to the chapel, she made a motion with her head, which. she repeated when she passed the (Ell de Boeuf. On the same evening that the necklace was delivered Madame met the cardinal on the terrace of the chateau, and told him that the queen was delighted. Her majesty could not then acknowledge the receipt of the necklace; but next day, if he would be, as if by chance, in the OEil de Boeuf, her majesty would, by the motion of her head, signify her approbation. The cardinal went, saw, and was satisfied. Meanwhile, as Madame Lamotte informed her dupe, the queen thought it advisable not to wear the necklace until she had mentioned its purchase to the king. The presence of the cardinal now becoming troublesome, a little note sent him again to Alsace. Madame Lamotte then despatched her husband with the necklace to London, where it was broken up; the small diamonds were reset in bracelets and rings, for the three accomplices; the remainder was sold to jewelers, and the money placed in the Bank of England in a fictitious name. The cardinal, in the meantime, induced the jewelers to write to the queen (if they could not see her), to thank her for the honor she had done them. They did so, and were soon summoned to explain their letter, which was an enigma to the queen; and the whole affair of the purchase, as far as the cardinal was concerned, was then explained to her majesty. This was in the beginning of July. From that moment Marie Antoinette acted in an unjust and undignified manner. Instead of exposing the manoeuvre, and having the authors of the fraud punished, the queen allowed herself to be guided by two of the most inveterate enemies of the cardinal, whom she left to their surveillance; and the jewelers were merely told to bring a copy of the agreement, and leave it with her majesty. Meanwhile, the first instalment in payment of the necklace was nearly due, and the cardinal being wanted to provide funds for it, he was recalled to Paris in the month of June, by a note assuring him that the realization of the queen's promises was near at hand, that she was making great efforts to meet the first 'payment, but that unforeseen expenditure rendered the matter difficult. The prince, however, began to think it strange that no change was apparent in the queen's behavior towards him in public, nor was the necklace worn; but, to satisfy him, Madame Lamotte arranged a private interview with the queen, between eleven and twelve o'clock, in a grove near Versailles. To personate her majesty at this rendezvous, the conspirators had chosen a certain Mademoiselle Leguet, whose figure, gait, and profile gave her a great resemblance to the queen. This new accomplice was not initiated into the secrets of the plot, but was told that she was to play her little part to mystify a certain nobleman of the court, for the amusement of the queen, who would be an unseen witness of the scene. It was rehearsed in the appointed grove: a tall man, in a blue great-coat and slouched hat, would approach and kiss her hand, with great respect. She was to say in a whisper: 'I have but a moment to spare; I am greatly pleased with all you have done, and am about to raise you to the height of power.' She was to give him a rose, and a small box containing a miniature. Footsteps would then be heard approaching, on which she was to exclaim, in the same low tone: 'Here are Madame, and Madame d'Artois! we must separate.' The scene took place as planned; the queen's relatives being represented by M. Lamotte and a confederate named Villette, who, approaching, cut short the cardinal's interview, of which he complained bitterly to his friends. Nevertheless, understanding that the queen was unable to pay the 300,000 livres, he endeavored to borrow them; when a note came to say, that if the payment could be delayed one month, the jewelers should receive 700,000 livres at the end of August, in lieu of the 300,000 livres due in July; 30,000 livres being tendered as interest, which Madame Lamotte contrived to pay out of the proceeds of the sale of the diamonds. This the jewelers took and gave the cardinal a receipt on account; but they refused all further delay, and daily pressed the prince for payment, and threatened to make use of the power his note gave them. ' Why,' exclaimed he, ' since you have had frequent access to her majesty, have you not mentioned the disagreeable situation in which her delay places you?' ' Alas! Monseigneur,' they replied, 'we have had the honor of speaking to her majesty on the subject, and she denies having ever given you such a commission, or received the necklace. To whom, my prince, can you have given it?' The cardinal was thunder struck: he replied, however, that he had placed the casket in Madame Lamotte's hands, and saw her deliver it into those of the queen's valet. 'At any rate,' he added, 'I have in my hands the queen's authorization, and that will be my guarantee.' The jewelers replied: 'If that is all you count upon, my lord, we fear you have been cruelly deceived.' Madame Lamotte was absent from Paris, but repaired thither, and arriving at the grand-almoner's in the middle of the night, assured him she had just left the queen, who threatened to deny having received the necklace, or authorised its purchase, ' and to make good her own position, would have me arrested, and ruin you;' at the seine time entreating his eminence to give her shelter until she could concert with her husband her means of escape. This was, in reality, a ruse to clear herself and criminate the cardinal, who, she declared on her arrest, had kept her a close prisoner for four and twenty hours, to prevent her disclosing that she had been employed to sell the diamonds for him. This took place early in August. An enemy of the cardinal now drew up a memorial of the whole affair, which, however, was not presented to the king until the 14th of August; and next morning being a great fete, while the grand-almoner, in his pontifical robes, was waiting to accompany her majesty to the chapel, he was summoned to the royal closet before Louis and Marie Antoinette, the memorialist, and two other court-dignitaries. The king, handing him the depositions of the jewelers, and the financier of whom the cardinal had endeavored to borrow for the queen 300,000 livres, bade him read them. This being done, the king asked what he had to say to these accusations. 'They are correct in the more material points, sire,' replied the cardinal. 'I purchased the necklace for the queen.' 'Who commanded you?' exclaimed she. 'Your majesty did so by a writing to that effect, signed, and which I have in my pocket book in Paris.' 'That writing,' exclaimed the queen, 'is a forgery!' The cardinal threw a significant glance at the queen, when the king ordered him to retire, and in a few minutes he was arrested and sent to the Bastile. A few days after, Madame Lamotte was arrested in the provinces, where she was entertaining a large party of friends; her husband had escaped, and she had sent her other accomplices out of the kingdom. She was taken to the Bastile on the 20th of August: when examined, she at first denied all knowledge of the necklace, though she admitted that she and her husband had been employed by the cardinal to dispose of a quantity of loose diamonds. She afterwards said that the necklace had been purchased by the cardinal to sell in fragments, in order to retrieve his affairs; and that he had acted with the connivance of Cagliostro, into whose hands the funds had passed. She denied all mention of the queen's name, and her tone was ironical and daring. Cagliostro and his wife were sent to the Bastile, where they were kept for many months; but nothing proved that they had been concerned in the affair, though the cardinal used to consult Cagliostro, in whose cabalistic art he had great faith. At this stage light unexpectedly broke in. Father Loth, a neighbor of Madame Lamotte, whom she had intrusted with her secret, revealed to the friends of the cardinal the parts played by Villette and Mademoiselle Leguet, who were accordingly arrested, one in Geneva, and the other in Belgium. Their evidence was conclusive as to the deception Madame Lamotte had practiced upon the cardinal with regard to the queen, and the other facts were easily proved. The testimony of Cagliostro also weighed heavily against her; and when confronted with the witnesses, in a violent rage she exclaimed: 'I see there is a plot on foot to ruin me; but I will not perish without disclosing the names of the great personages yet concealed behind the curtain!' This strange drama was at length brought to a close on the 31st of May 1786; when, in the trial before the Criminal Court, the prince cardinal was proved innocent of all fraud, but was ridiculed for his extreme credulity; was ordered by the king to resign his posts at court; and was exiled to his abbey of La Chaise Dieu, in the mountains of Auvergne. The wretched woman, Lamotte, was sentenced to be flogged, branded on both shoulders, and imprisoned for life. When the former part of the sentence was executed, she most foully abused the queen; and though she was gagged, enough was heard to form the ground of the vilest calumnies. Her husband, who had escaped to England, was condemned by default; when he threatened to publish a pamphlet compromising the queen and her minister, Baron de Breteuil, if his wife were not set free. This was treated with contempt; but, ten months after, Madame Lamotte was permitted to escape to England, whither the Duchess of Polignac was sent to purchase the silence of the infamous Lamottes with a large sum of money. The bribe was thrown away, for though one edition of the slanderous pamphlet, or memoir, was burned, a second was published some time after; and the copies which are now extant in the Imperial Library of Paris, were found in the palace of Versailles, when it was taken ,possession of by the Republican government. THE WHISTLE DRINKING CUP The drinking customs of various nations would form a curious chapter in ethnology. The Teutonic races have, however, the most claim to be considered 'potent in potting.' The Saxons were great drinkers; and took with them to their graves their ornamental ale-buckets and drinking glasses, the latter made without foot or stand, so that they must be filled and emptied by the drinker before they could be set down again on the festive board. Mighty topers they were, and history records some of their drinking bouts. Notwithstanding the assertion of Iago, that 'your Dane, your German, and your swag bellied Hollander, are nothing to your English' in powers of drinking, it may be doubted if the Germans have ever been outdone, Certainly no persons have bestowed more thought on quaint inventions for holding their liquors, or enforcing large consumption, than they have. The silversmiths of Augsburg and Nuremberg, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, devoted a large amount of invention to the production of drinking cups, taking the form of men, animals, birds, &e., of most grotesque design. Our engraving represents one surmounted by a wind-mill. It will he perceived that the cup must be held in the hand to be filled, and retained there till it be emptied, as then only it can be set upon the table. The Dr.inker having swallowed the contents, blew up the pipe at the side, which gave a shrill whistle, and set the sails of the wind-mill in motion also. The power of the blow, and the length of the gyration, were indicated in a small dial upon the front of the mill, and also in some degree testified to the state of the consumer. Among the songs of Burns is one upon a whistle, used by a Dane of the retinue of Anne of Denmark, which was laid upon the table at the commencement of the orgie, and won by whoever was last able to blow it. The Dane conquered all comers, until Sir Robert Lawrie of Maxwelton, 'after three days and three nights' hard contest, left the Scandinavian under the table.' On 16th October 1789, a similar contest took place, which has been immortalized in Burns's verses. NATHANIEL LLOYD'S WILL, ODD BEQUESTSOn the 16th of October 1769, Nathaniel Lloyd, of Twickenham, Middlesex, Esquire, completed his testament in the following terms: What I am going to bequeath, When this frail spark submits to death; But still I hope the spark divine With its congenial stars shall shine; My good Executors, fulfil, I pray ye, fairly, my last will, With first and second codicil. First, I give to dear Lord Hinton, At Tryford school not at Winton, One hundred guineas for a ring, Or some such memorandum thing; and truly, much I should have blundered, Had I not giv'n another hundred To Vero, Earl Poulett's second son, Who dearly loves a little fun. Unto my nephew, Robert Longden, Of whom none says he ever has wrong done, Tho' civil law he loves to lash, I give two hundred pounds in cash. One hundred pounds to my niece Tuder (With loving eyes one Matthew view'd her) And to her children just among 'em A hundred more, and not to wrong 'ern, In equal shares I freely give it, Not doubting but they will receive it. To Sally Crouch and Mary Lee, If they with Lady Poulett be, Because they would the year did dwell In Twickenham House, and served full well, When Lord and Lady both did stray Over the hills and far away: The first, ten pounds: the other twenty; And, girls, I hope that will content ye. In seventeen hundred, sixty-nine, This with my hand I write and sign, The sixteenth day of fair October, In merry mood, but sound and sober; Past my threescore-and-fifteenth year, With spirits gay and conscience clear, joyous and frolicsome, though old, And like this day-serene, but cold; To foes well-wishing, and to friends most kind, In perfect charity with all mankind. For what remains, I must desire, To use the words of Matthew Prior: 'Supreme! All wise! Eternal Potentate! Sole Author! sole Disposer of my Fate! Enthron'd in Light and Immortality! Whom no man fully sees, and none can see! Original of Beings! Power Divine! Since that I think, and that I live, is thine! Benign Creator! let thy plastic hand Dispose of its own effect! Let thy command Restore, Great Father, thy instructed son, And in my act, may Thy great will be done. To be thus quaint and eccentric in one of the most solemn affairs of life, is of by no means unfrequent occurrence among the denizens of this cloudy island. Some men choose to burden their executors with a great number of injunctions, partly to express certain tastes and prejudices, but mainly, as we may presume, for the vanity of causing some little sensation about themselves when they are no more. The following is a notable example: A True Copy of the Last Will and Testament of Mr. Benjamin Dod, Citizen and Linen Draper, who lately fell from his Horse, and Dy'd soon after. In the Name of God, Amen. I, Benjamin Dod, citizen and mercer of London, being in health of body, and good and perfect memory, do make this my last will and Testament in manner and form following (that is to say): First, my soul I commend to Almighty God that gave it me, and my body to the earth from whence it came. I desire to be interr'd in the parish church of St. John, Hackney, in the county of Middlesex, about eleven o'clock at night, in a decent and frugal manner, as to Mr. Robert Atkins shall seem meet, the management whereof I leave to him. I desire Mr. Brown to preach my funeral sermon; but if he should happen to be absent or dead, then such other persons as Mr. Robert Atkins shall appoint: and to such minister that preaches my funeral sermon I give five guineas. 'Item: I desire four and twenty persons to be at my burial, out of which Messrs J. Low, &c. naming six persons to be pall bearers: but if any of them be absent or dead, I desire Mr. Robert Atkins to appoint others in their room, to every of which four and twenty persons so to be invited to my funeral, I give a pair of white gloves, a ring of ten shillings' value, a bottle of wine at my funeral, and half a crown to spent at their return that night, to drink my soul's health, then on her journey to purification in order to eternal rest. I appoint the room where my corps shall lye, to be hung with black, and four and twenty wax candles to be burning. On my coffin to be affixed a cross, and this inscription - Jesus Hominum Salvator I also appoint my corps to be carried in a hearse, drawn with six white horses, with white feathers, and follow'd by six coaches, with six horses to each coach, to carry the four and twenty persons. I desire Mr. John Spicer may make the escutcheons, and appoint an undertaker, who shall be a noted churchman. What relations have a mind to come to my funeral may do it without invitation. Item: I give to forty of my particular acquaintance, not at my funeral, to every of them a gold ring of ten shillings' value; the said forty persons to be named by Mr. Robert Atkins. As for mourning, I leave that to my executors hereafter named; and I do not desire them to give any to whom I shall leave a legacy. After enumerating a number of legacies, &c., the testator concludes thus: I will have no Presbyterians, moderate Low churchmen, or occasional Conformists, to be at, or have anything to do with, my funeral. I die in the faith of the true Catholick Church. I desire to have a Tombstone over me, with a Latin inscription; and a lamp, or six wax candles, to burn seven days and nights together thereon. The will of Peter Campbell, of Darley, dated October 20, 1616, contained the following passage: Now for all such household goods at Darley, whereof John Howson hath an inventory, my will is, that my son Roger shall have them all towards housekeeping upon this condition, that if, at any time hereafter, any of his brothers or sisters shall find him taking of tobacco, that then he or she, so finding him, and making just proof to my executors, shall have the said goods, or the fall value thereof, according as they shall be praised. Some men, again, have an amiable dying satisfaction in charging their wills with a sting or a stab at some relative or other person who has not behaved well, or has (or is supposed to have) been guilty of some special delict towards the testator. Some have a similar pleasure in shewing their contempt for their own kind by careful provision for favourite cats, dogs, and parrots. Others, good easy-natured souls, love to charge their wills with a joke, which they know will provoke a smile from their old friends when they are lying cold in the grave. A few examples of these various testamentary eccentricities follow: 1788. 'I, David Davis, of Clapham, Surrey, do give and bequeath to Mary Davis, daughter of Peter Delaport, the sum of 5s, which is sufficient to enable her to get drunk for the last time at my expense.' 1782. 'I, William Blackett, governor of Plymouth, desire that my body may be kept as long as it may not be offensive; and that one or more of my toes or fingers may be cut off, to secure a certainty of my being dead. I also make this request to my dear wife, that as she has been troubled with one old fool, she will not think of marrying a second.' 1781. 'I, John Aylett Stow, do direct my executors to lay out five guineas in the purchase of a picture of the viper biting the benevolent hand of the person who saved him from perishing in the snow, if the same can be bought for that money; and that they do, in memory of me, present it to Esq., a King's Counsel, whereby he may have frequent opportunities of contemplating on it, and, by a comparison between that and his own virtue, be able to form a certain judgment which is hest and most profitable, a grateful remembrance of past friendship and almost parental regard, or ingratitude and insolence. This I direct to be presented to him in lieu of a legacy of £3000, which I had, by a former will, now revoked and burnt, left him.' Extract from the Will of S. Church, in 1793. 'I give and devise to my son, Daniel Church, only one shilling, and that is for him to hire a porter to carry away the next badge and frame he steals.' 1813. 'I, Elizabeth Orby Hunter, of Upper Seymour Street, widow, do give and bequeath to my beloved parrot, the faithful companion of 25 years, an annuity for its life of 200 guineas a year, to be paid half-yearly, as long as this beloved parrot lives, to whoever may have the care of it, and proves its identity; but the above annuity to cease on the death of my parrot; and if the person who shall or may have care of it, should substitute any other parrot in its place, either during its life or after its death, it is my positive will and desire, that the person or persons so doing shall refund to my heirs or executors the sum or sums they may have received from the time they did so; and I empower my heirs and executors to recover it from whoever could be base enough to do so. And I do give and bequeath to Mrs. Mary Dyer, widow, now dwelling in Park Street, Westminster, my foresaid parrot, with its annuity of 200 guineas a year, to be paid her half yearly, as long as it lives; and if Mrs. Mary Dyer should die before my beloved parrot, I will and desire that the aforesaid annuity of 200 guineas a year may be paid to whoever may have the care of my parrot as long as it lives, to be always the first paid annuity; and I give to Mrs. Mary Dyer the power to will and bequeath my parrot and its annuity to whomsoever she pleases, provided that person is neither a servant nor a man it must be bequeathed to some respectable female. And I also will and desire that no person shall have the care of it that can derive any benefit from its death; and if Mrs. Dyer should neglect to will my parrot and its annuity to any one, in that case, whoever proves that they may have possession of it, shall be entitled to the annuity on its life, as long as it lives, and that they have possession of it, provided that the person is not a servant or a man, but a respectable female; and I hope my executors will see it is in proper and respectable hands; and I also give the power to whoever possesses it, and its annuity, to any respect-able female on the same conditions. And I also will and desire, that 20 guineas may be paid to Mrs. Dyer directly on my death, to be expended on a very high, long, and large cage for the foresaid parrot. It is also my will and desire, that my parrot shall not be removed out of England. I will and desire that whoever attempts to dispute this my last will and testament, or by any means neglect, or tries to avoid paying my parrot's annuity, shall forfeit whatever I may have left them; and if any one that I have left legacies to attempt bringing in any bills or charges against me, I will and desire that they forfeit whatever I may have left them, for so doing, as I owe nothing to any one. Many owe to me both gratitude and money, but none have paid me either.' 1806. 'I, John Moody, of Westminster, boot-maker, give to Sir F. Burdett, Bart., this piece of friendly advice, to take a special care of his conduct and person, and never more to be the dupe of artful and designing men at a contested election, or ever amongst persons moving in a higher sphere of life; for place-men of all descriptions have conspired against him, and if prudence does not lead him into private life, certain destruction will await him.' 1810. 'Richard Crawshay, of Cyfartha, in the county of Glamorgan, Esq. 'To my only son, who never would follow my advice, and has treated me rudely in very many instances; instead of making him my executor and residuary legatee (as till this day he was), I give him £100,000.' 1793. 'I, Philip Thicknesse, formerly of London, but now of Bologna, in Prance, leave my right hand, to be cut off after my death, to my son, Lord Audley; and I desire it may be sent to him, in hopes that such a sight may remind him of his duty to God, after having so long abandoned the duty he owed to a father who once affectionately loved him. 1770. 'I, Stephen Swain, of the parish of St. Olave, Southwark, give to John Abbot, and Mary, his wife, 6d each, to buy for each of them a halter, for fear the sheriffs should not be provided.' 1794. 'I, Wm. Darley, late of Ash, in the county of Herts, give unto my wife, Mary Darley, for picking my pocket of 60 guineas, and taking up money in my name, of John Pugh, Esq., the sum of one shilling.' 1796. 'I, Catharine Williams, of Lambeth, give and bequeath to Mrs. Elizabeth Paxton £10, and £5 a year, to be paid weekly by my husband, to take care of my cats and dogs, as long as any of them shall live; and my desire is that she will take great care of them, neither let them be killed or lost. To my servant boy, George Smith, £10 and my jackass, to get his living with, as he is fond of traffic.' 1785. 'I, Charles Parker, of New Bond Street, Middlesex, bookseller, give to Elizabeth Parker, the sum of £50, whom, through my foolish fondness, I made my wife, without regard to family, fame, or fortune; and who, in return, has not spared, most unjustly, to accuse me of every crime regarding human nature, save highway robbery.' Amongst jocular bequests, that of David Hume to his friend John Home, author of Douglas, may be considered as one of the most curious. John Home liked claret, but detested port wine, thinking it a kind of poison; and the two friends had doubt-less had many discussions on this subject. They also used to have disputes as to which of them took the proper way of spelling their common family-name. The philosopher, about a fortnight before his death, wrote with his own hand the following codicil to his will: 'I leave to my friend, Mr. John Home, of Kilduff, ten dozen of my old claret at his choice, and one single bottle of that other liquor called port. I also leave him six dozen of port, provided that he attests under his hand, signed John Hume, that the has himself alone finished that bottle at two sittings. By this concession, he will at once terminate the only two differences that ever arose between us concerning temporal matters.' Somewhat akin to this humor was that shewn in a verbal bequest of a Scotch judge named Lord Forglen, who died in 1727. 'Dr. Clerk, who attended Lord Forglen at the last, told James Boswell's father, Lord Auchinleck, that, calling on his patient the day his lordship died, he was let in by his clerk, David Reid. 'How does my lord do?' inquired Dr. Clerk. 'I houp he's weel' answered David, with a solemnity that told what he meant. He then conducted the doctor into a room, and skewed him two dozen of wine under a table. Other doctors presently came in, and David, making them all sit down, proceeded to tell them his deceased master's last words, at the same time pushing the bottle about briskly. After the company had taken a glass or two, they rose to depart; but David detained them. 'No, no, gentlemen; not so. It was the express will of the deceased that I should fill ye a' fou, and I maun fulfil the will o' the dead.' All the time the tears were streaming down his cheeks. 'And, indeed,' said the doctor afterwards in telling the story, 'he did fulfil the will o' the dead, for before the end o't there was na ane of us able to bite his ain thoomb' JOHN HUNTER'S MUSEUMIt is doubtful whether any private individual ever formed a museum more complete and valuable than that of John Hunter, now under the care of the Royal College of Surgeons, in Lincoln's Inn Fields. Whatever else the great surgeon was doing, he never forgot or neglected his museum. In 1755, when his brother Dr. William hunter was a surgeon and lecturer of eminence, John was his assistant, and helped him in making anatomical preparations. He soon, however, went far beyond his mere duties as an assistant, and examined all the living and dead animals he could get hold of, to compare their structure with that of the human body. He made friends with the keepers of all the traveling menageries, and lost no opportunity of profiting by the facilities thus afforded. A mangy dog, a dead donkey, a sick lion, all alike were made contributary to the advancement of science in the hands of John Hunter. He took a house in Golden Square in 1764, and then built a second residence at Earl's Court, where he might carry on experiments in science. After having been made a member of the College of Surgeons, he removed from Golden Square to Jermyn Street, where he packed all the best rooms in the house full of anatomical specimens and preparations. He married in 1771, and his wife thereafter lived at Earl's Court, for there was no room for her among the physiological and pathological wonders of Jermyn Street. Indeed, for more than twenty years, he was accustomed to carry on his favourite researches at Earl's Court, only being in London a sufficient time each day to attend to his practice as a surgeon. His collection increased so rapidly, that the house in Jermyn Street became filled to repletion; insomuch that, in 1782, he took a larger house on the east side of Leicester Square. Here he built a new structure expressly as a museum, comprising a fine room fifty two feet by twenty eight, lighted at the top, and provided with a gallery all round. Sir Joseph Banks aided John Hunter out of his own ample store of natural history specimens, and the museum soon became a wealthy one. Mr. Home, a brother in law, who had been an assistant army surgeon, came to reside with him as a sort of curator of the museum. Hunter also employed a Mr. Bell for fourteen years, in making anatomical Drawings and preparations; while he himself was accumulating a vast mass of MS. papers building up almost a complete system of physiology and surgery, on the evidence furnished by the specimens in his museum. Hunter was always poor, and very frequently embarrassed, by the expenses which his scientific enterprise entailed upon him, and this notwithstanding the fact that his professional income reached £5000 a year for some years before his death. In 1794, he began to open his museum occasionally to the public, and justly prided himself on the scientific way in which it was arranged. Being a hasty and irritable man, he soon took offence, and was not readily appeased; and he himself predicted that any sudden or violent anger would probably kill him. The result mournfully verified his prediction; for, on the 16th October 1795, having had a very exciting quarrel with some of the members at the College of Surgeons, he dropped down dead in the attempt to suppress his feelings. In his will, he directed that his museum, the pride of his life, should he offered to the nation if anything like a fair sum were tendered for it; in order that it might be retained in the country. Failing in this, it was to be offered to certain foreign governments, in succession; and if all these attempts failed, it was to be disposed of by private contract. After much negotiation, the government bought the splendid collection, in 1799, for £15,000. The question, what to do with it? had then to be decided, and the following arrangement was come to. The College of Surgeons received a new charter in 1800, constituting it a 'Royal' College, and giving it increased powers. The Hunterian Collection was intrusted to the keeping of the college, on condition of the public being allowed access to it; and twenty four 'Hunterian Lectures' on surgery being given annually by the college. The government granted £27,500 to construct a building for the reception of the collection; but it was many years before the museum was really opened. One painful circumstance connected with this museum roused the indignation of the whole medical profession of Europe. John Hunter left a vast mass of manuscripts of priceless value, recording the results of forty years' researches in comparative and pathological anatomy and physiology. This treasure was placed in the museum. Mr. (afterwards Sir Everard) Home was one of the executors, and also one of the trustees. He took these manuscripts to his own house, about 1810, under pretense of Drawing up a catalogue of them; and no entreaties or remonstrances would ever induce him to return them. He kept them ten or twelve years, and then burned them! The only reason he assigned was, that John Hunter had requested him to do so. The world viewed the matter otherwise. Year after year, while the manuscripts were in his possession, Sir Everard poured forth scientific papers in such profusion as astonished all the physicians and anatomists of Europe, who had hitherto been ignorant of his possessing such attainments. Then, after years of surprise and disappointment at the non-return of the Hunter manuscripts, the act of their destruction was openly admitted by Home, and the source of his scientific inspiration now became tolerably manifest. Unhappily, this disgraceful transaction remains beyond a doubt. The trustees and the board of curators, indignantly remonstrated with Home in 1824 and 1825, and compelled him to make an attempt to vindicate himself, but none of his excuses or explanations could do away with the one cruel fact, that the invaluable manuscripts were irrevocably gone. The Hunterian Museum, comprising 22,000 specimens, occupies a fine suite of rooms and galleries at the Royal College of Surgeons, on the south side of Lincoln's Inn Fields. Most of them are valuable only to medical men; but some, such as the skeletons of the Bosjesman, the Irish giant, and the Sicilian dwarf, and the embalmed body of the wife of Martin Van Butchell, a celebrated quack doctor in the last century, will be viewed by all with the greatest interest. |