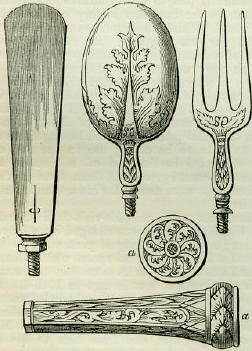

16th AprilBorn: Sir Hans Sloane, naturalist, 1660, Killileagh; George Montagu, Earl of Halifax, 1661, Horton; John Law, speculative financier, 1671, Edinburgh. Died: Aphra Behn, poetess, 1689; George Louis, Comte De Buffon, naturalist, 1788, Montbard; Dr. George Campbell, theologian, 1796; Arthur Young, writer on agriculture, 1820, Bradfield; Muzio Clementi, celebrated pianist, 1820; Henry Fuseli, artist, 1825, Putney Hill; - Reynolds, dramatist, 1841; Pietro Dragonetti, eminent musician, 1846, London; Madame Tussaud (wax figures), 1850, London. Feast Day: Eighteen martyrs of Saragossa, 304. St. Turibius, Bishop of Astorga, about 420. St. Fructuosus, Arch-bishop of Braga, 665. St. Magnus, of Orkney, martyr, 1104. St. Dimon, recluse, patron of shepherds, 1186. St. Joachim of Sienna, 1305 APHRA BEHNAphra Behn, celebrated as a writer and a wit, was born in the city of Canterbury, in the reign of Charles I. Her father, whose name was Johnson, being of a good family and well connected, obtained, through the interest of his relative, Lord Willoughby, the Appointment of Lieutenant-General of Surinam, and set out with his wife and children to the West Indies. Mr. Johnson died on the voyage, but his family reached Surinam, and settled there for some years. While here, Aphra became acquainted with the American Prince Oroonoka, and his beloved wife Imoinda, and the adventures of this pair became the materials of her first novel. On returning to London, she became the wife of Mr. Behn, a Dutch merchant resident in that city. How long Mr. Behn lived after his marriage is not known, but, probably, not long; for when we next hear of Mrs. Behn, her wit and abilities had brought her into high repute at the Court of Charles II; so much so, that Charles thought her a fit and proper person to be entrusted with the transaction of some affairs of importance abroad during the Dutch war. Our respect for official English is by no means increased when we learn that these high-sounding terms merely mean that she was to be sent over to Antwerp as a spy! However, by her skill and intrigues, but more by the influence she possessed over Vander Albert, she succeeded so well as to obtain information of the design of the Dutch to sail up the Thames and burn the English ships in their harbours, and at once communicated her information to the English Court. Although subsequent events proved her intelligence to be well founded, it was only laughed at at the time, which probably determined her to drop all further thoughts of political affairs, and during the remainder of her stay at Antwerp to give herself up to the gallantries and gaieties of the place. On her voyage back to England, she was very near being lost. The vessel foundered in a storm, but fortunately in sight of land, so that the passengers were saved by boats from the shore. The rest of her life was devoted to pleasure and the muses. Her writings, which are numerous, are nearly forgotten now, and from the opinion of several writers, it is well they should be. The following are the principal: three vols. of Miscellany Poems; seventeen Plays; two volumes of History and Novels; and a translation of M. Fontenelle's History of Oracles, and Plurality of Worlds. A plain black marble slab covers her grave in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, bearing the following inscription: Mrs. APHARRA BEHN DIED APRILL THE 16TH, 1689 Here lies a proof that wit can never be Defence enough against mortality. Great poetess, 0 thy stupendous lays The world admires, and the Muses praise. MADAME TUSSAUDThe curious collection of wax-work figures exhibited in Baker-street, London, under the name of Madame Tussaud, is well known in England. Many who are no longer in their first youth must also have a recollection of the neat little figure of Madame Tussaud herself, seated in the stair of approach, and hard to be distinguished in its calm primness from the counterfeits of humanity which it was the business of her life to fabricate. Few, however, are aware of the singularities which marked the life of Madame Tussaud, or of the very high moral merits which belonged to her. She had actually lived among the celebrated men of the French Revolution, and framed their portraits from direct observation. It was her business one day to model the horrible countenance of the assassinated Marat, whom she detested, and on another to imitate the features of his beautiful assassin, Charlotte Corday, whom she admired and loved. Now, she had a Princess Lamballe in her hands; anon, it was the atrocious Robespierre. At one time she was herself in prison, in danger of the all-devouring guillotine, having there for her associates Madame Beauharnais and her child, the grandmother and mother of the Emperor Napoleon III. Escaping from France, she led for many years a life of struggle and difficulty, supporting herself and her family by the exercise of her art. Once she lost her whole stock by shipwreck on a voyage to Ireland. Meeting adversity with a stout heart, always industrious, frugal, and considerate, the ingenious little woman at length was enabled to set up her models in London, where she had forty years of constant prosperity, and where she died at the age of ninety, in the midst of an attached and grateful family, extending to several generations. Let ingenuity be the more honoured when it is connected, as in her case, with many virtues. THE SWEATING SICKNESSApril 16th, 1551, the sweating sickness broke out at Shrewsbury. This was the last appearance of one of the most remarkable diseases recorded in history. Its first appearance was in August 1485, among the followers of Henry VII who fought and gained the memorable battle of Bosworth Field. The battle was contested on the 22nd of August, and on the 28th the king entered London, bringing in his train the fatal and previously unknown pestilence. The 'Swetynge Sykenesse,' as it is termed by the old chroniclers, immediately spread its ravages among the crowded, unhealthy dwellings of the citizens of London. Two lord mayors and six aldermen, having scarcely laid aside the state robes in which they had received the Tudor king, died in the first week of the terrible visitation. The national joy and public festivities, consequent on the conclusion of the long struggle between the rival houses of York and Lancaster, were at once changed to general terror and lamentation. The coronation of Henry, an urgent measure, as it was expected to extinguish the last scruples that some might entertain regarding his right to the throne, was of necessity postponed. The disease spread over all England with fearful rapidity. It seems to have been a violent inflammatory fever, which, after a short rigor, prostrated the vital powers as with a blow; and, amidst a painful oppression at the stomach, headache, and lethargic stupor, suffused the whole body with a copious and disgustingly foetid perspiration. All this took place in a few hours, the crisis being always over within the space of a day and night; and scarcely one in a hundred recovered of those who were attacked by it. Hollinshed says: Suddenly, a deadly burning sweat so assailed their bodies and distempered their blood with a most ardent heat, that scarce one among an hundred that sickened did escape with life, for all in manner, as soon as the sweat took them, or a short time after, yielded the ghost. Kaye, the founder of Caius College, Cambridge, and the most eminent physician of his day, who carefully observed the disease at its last visitation, relates that its ' sudden sharpness and unwont cruelness passed the pestilence (the plague). For this (the plague) commonly giveth three or four, often seven, sometimes nine, sometimes eleven, and sometimes fourteen days respect to whom it vexeth. But that (the sweating sickness) immediately killed. Some in opening their windows, some in playing with their children at their street doors, some in one hour, many in two, it destroyed, and, at the longest, to them that merrily dined it gave a sorrowful supper. As it found them, so it took them, some in sleep, some in wake, some in mirth, some in care, some fasting, and some full, some busy, and some idle, and in one house, sometimes three, sometimes four, sometimes seven, sometimes eight, sometimes more, some-times all. Though the sweating sickness of 1485 desolated the English shores of the Irish Channel, and the northern border counties of England, yet it did not penetrate into either Ireland or Scotland. It disappeared about the end of the year; a violent tempest that occurred on the 1st of January 1486, was supposed to have swept it away for ever. The slight medical knowledge of the period found itself utterly unable to cope with the new disease. No resource was therefore left to the terrified people, but their own good sense, which fortunately led them to adopt the only efficient means that could be pursued. Violent medicines were avoided. The patient was kept moderately warm, a small quantity of mild drink was given, but total abstinence from food was enjoined until the crisis of the malady had passed. Those who were attacked in the day, in order to avoid a chill, went immediately to bed with-out taking off their clothes, and those who sickened at night did not rise, carefully avoiding the slightest exposure to the air of either hand or foot. Thus they carefully guarded against heat or cold, so as not to encourage the perspiration by the former, nor check it by the latter; bitter experience having taught that either was certain death. In 1506, the sweating sickness broke out in London for the second time, but the disease exhibited a much milder character than it did during its first visitation; numbers who were attacked by it recovered, and the physicians of the day rejoiced triumphantly, attributing the cures to their own skill, instead of to the milder form of the epidemic. It was not long till they discovered their error. In 1517, the disease broke out in England for the third time, with all its pristine virulence. It ravaged England for six months, and as before did not penetrate into Ireland or Scotland. It reached Calais, however, then an English possession, but did not spread farther into France. As eleven years elapsed between the second and third visitation of this fell destroyer, so the very same period intervened between its third and fourth appearance, the latter taking place in 1528. The previous winter had been so wet, that the seed corn had rotted in the ground. Some fine weather in spring gave hopes to the husbandman, but scarcely had the fields been sown when a continual series of heavy rains destroyed the grain. Famine soon stalked over the land, and with it came the fatal sweating sickness. This, as far as can be collected, was its most terrible visitation, the old writers de-scribing it as The Great Mortality. All public business was suspended. The Houses of Parliament and courts of law were closed. The king, Henry VIII, left London, and endeavoured to avoid the epidemic by continually travelling from place to place, till, becoming tired of so unsettled a life, he determined to await his destiny at Tittenhanger. There, with his first wife, Katherine of Arragon, and a few favourites, he lived in total seclusion from the outer world, the house being surrounded with large fires, which night and day were kept constantly burning, as a means of purifying the atmosphere. There are no accurate data by which the number of persons destroyed by this epidemic can be estimated, but they must have been many, very many. The visitation lasted much longer than the previous ones. Though the greater number of deaths occurred in 1528, the disease was still prevalent in the following summer. As before, the epidemic did not extend to Scotland or Ireland. It was even affirmed and believed that natives of those countries were never attacked by it, though dwelling in England; that in Calais it spared the French, the men of English birth alone becoming its victims; that, in short, it was a disease known only in England, and fatal only to Englishmen; consequently, the learned gave it the name of Sudor Anglicus-the English sweat. And the learned writers of the period all cordially agreed in ascribing the English pestilence to the sins of Englishmen, though they differed in opinion as to the particular sins which called down so terrible a manifestation of Divine displeasure. Not one of them conjectured the real causes of the epidemic, namely, the indescribable filthiness of English towns and houses, and the scarcity and disgusting unwholesomeness of the people's food. The disease soon gave the lie to the expression Sudor Anglices by spreading into Germany, and there committing frightful ravages. On its last visit to England, in April 1551, it made its first appearance at Shrewsbury. It was found to have undergone no change. It attacked its hapless victims at table, on journeys, during sleep, at devotion or amusement, at all times of the day or night. Nor had it lost any of its malignity, killing its victims sometimes in less than an hour, while in all cases the space of twenty-four hours decided the fearful issue of life or death. Contemporary historians say that the country was depopulated. Women ran about negligently clothed, as if they had lost their senses, and filled the air with dismal outcries and lamentations. All business came to a stand. No one thought of his daily avocations. The funeral bells tolled night and day, reminding the living of their near and inevitable end. Breaking out at Shrewsbury, it spread westward into Wales, and through Cheshire to the north-western counties; while on the other side, it extended to the southern counties, and easterly to London, where it arrived in the beginning of July. It ravaged the capital for a month, then passed along the east coast of England towards the north, and finally ceased about the end of September. Thus, in the autumn of 1551, the sweating sickness vanished from the earth; it has never reappeared, and in all human probability never will, for the conditions under which a disease of its nature and malignity could occur and extend itself do not now exist. Modern medical science avers that the Sudor Anglices was a rheumatic fever of extraordinary virulence; still of a virulence not to be wondered at, when we take into consideration the deficiency of the commonest necessaries of life, that prevailed at the period in which it occurred. BATTLE OF CULLODEN - PRINCE CHARLES'S KNIFE-CASEOn the 16th of April 1746, was fought the battle of Culloden, insignificant in comparison with many other battles, from there being only about eight thousand troops engaged on each side, but important as finally setting at rest the claims of the expatriated line of the house of Stuart to the British throne. The Duke of Cumberland, who commanded the army of the government, used his victory with notable harshness and cruelty; not only causing a needless slaughter among the fugitives, but ordering large numbers of the wounded to be fusilladed on the field: a fact often doubted, but which has been fully proved. He probably acted under an impression that Scotland required a severe lesson to be read to her, the reigning idea in England being that the northern kingdom was in rebellion, whereas the insurgents represented but a small party of the Scottish people, to whom in general the descent of a parcel of the Highland clans with Charles Edward Stuart was as much a surprise as it was to the court of St. James's. The cause of the Stuarts had, indeed, extremely declined in Scotland by the middle of the eighteenth century, and the nation was turning its whole thoughts to improved industry, in peaceful submission to the Brunswick dynasty, when the romantic enterprise of Prince Charles, at the head of a few hundred Camerons and Macdonalds, came upon it very much like a thunder-cloud in a summer sky. The whole affair of the Forty-five was eminently an affair out of time, an affair which took its character from a small number of persons, mainly Charles himself and a few West Highland chieftains, who had pledged themselves to him, and after all went out with great reluctance. The wretched wanderings of the Prince for five months, in continual danger of being taken and instantly put to death, form an interesting pendant to the romantic history of the enterprise itself. Thirty thousand pounds was the fee offered for his capture; but, though many scores of persons had it in their power to betray him, no one was found so base as to do it. A curious circumstance connected with his wanderings has only of late been revealed, that, during nearly the whole time, he himself had a large command of money, a sum of about twenty-seven thousand pounds in gold having come for him too late to be of any use in the war, and been concealed in the bed of a burn in the Cameron's country, whence, from time to time, portions of it were drawn for his use and that of his friends. When George IV paid his visit to Scotland in 1822, Sir Walter Scott was charged by a lady in Edinburgh, with the duty of presenting to him the pocket knife, fork, and spoon which Charles Edward was believed to have used in the course of his marches and wanderings in 1745-6. The lady was, by Sir Walter Scott's acknowledgment Mary Lady Clerk, of Penicuik. This relic of Charles, having subsequently passed to the Marquis of Conyngham, and from him to his son Albert, first Lord Londesborough, is now preserved with great care amidst the valuable collection of ancient plate and bijouterie at Grimston Park, Yorkshire.  The case is a small one covered with black shagreen; for portability, the knife, fork, and spoon are made to screw upon handles, so that the three articles form six pieces, allowing of close packing, as shewn in our first cut. The second cut exhibits the articles themselves, on a scale of half their original size; one of the handles being placed below, while the rose pattern on the knob of each is shewn at a. They are all engraved with an ornament of thistle leaves, and the spoon and fork marked with the initials C. S., as will be better seen on reversing the engraving. The articles being impressed with a Dutch plate stamp, we may presume that they were manufactured in Holland.  On reverting to the chronicles of the day, we find that the king, in contemplation of his visit to Scotland, expressed a wish to possess some relic of the 'unfortunate Chevalier,' as he called him; and it was in the knowledge of this fact, that Lady Clerk commissioned Sir Walter Scott to present to his Majesty the articles here described. On the king arriving in Leith Road, Sir Walter went out in a boat to present him with a silver cross badge from 'the ladies of Scotland,' and he took that opportunity of handing him the gift of Lady Clerk, which the king received with marked gratification. At a ball a few days afterwards, he gave the lady his thanks in person, in terms which showed his sense of the value of the gift. He was probably by that time aware of an interesting circumstance in her own history connected with the Forty-five. Born Mary Dacres, the daughter of a Cumberland gentleman, she had entered the world at the time when the Prince's forces were in possession of Carlisle. While her mother was still confined to bed, a highland party came to the house; but the officer in command, on learning the circumstances, not only restrained his men from giving any molestation, but pinned his own white rosette or cockade upon the infant's breast, that it might protect the household from any trouble from others. This rosette the lady kept to her dying day, which was not till several years subsequent to the king's visit. Her ladyship retained till past eighty an erect and alert carriage, which, together with some peculiarities of dressing, made her one of the most noted street figures of her time. With Sir Walter she was on the most intimate terms. The writer is enabled to recall a walk he had one day with this distinguished man, curling at Mr. Constable's warehouse in Princes-street, where Lady Clerk was purchasing some books at a side counter. Sir Walter, passing through to the stairs by which Mr. Constable's room was reached, did not recognise her ladyship, who, catching a sight of him as he was about to ascend, called out, '0h, Sir Walter, are you really going to pass me?' He immediately turned to make his usual cordial greetings, and apologised with demurely waggish reference to her odd dress, 'I'm sure, my lady, by this time I might know your back as well as your face.' It is understood in the Conyingham family, that the knife-case came to Lady Clerk 'through the Primrose family,' probably referring to the widow of Hugh third Lord Primrose, in whose house in London Miss Flora Macdonald was sheltered after her liberation from a confinement she underwent for her concern in promoting the Prince's escape. We are led to infer that Lady Primrose had obtained the relic from some person to whom the Chevalier had given it as a souvenir at the end of his wanderings. |