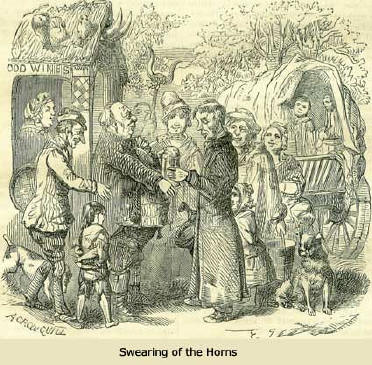

15th JanuaryBorn: Dr. Samuel Parr, 1747, Harrow; Dr. John Aikin, 1747, Knihsworth; Talma, French tragedian, 1763, Paris; Thomas Crofton Croker, 1798. Died: Father Paul Sarpi, 1623; Sir Philip Warwick, 1683. Feast Day: St. Paul, the First Hermit, 342. St. Isidore, priest and hermit, c. 390. St. Isidore, priest and hospitaller of Alexandria, 403. St. John Calybite, recluse, 450. St. Maurus, abbot, 584. St. Main, abbot. St. Ita or Mida, virgin abbess, 569. St Bonitus, bishop of Auvergne, 710. DR. SAMUEL PARR As a literary celebrity, occupied no narrow space in the eyes of our fathers. In our own age, he has shrunk down into his actual character of only a literary eccentricity. It seems almost incredible that, after his death in 1825, there should have been a republication of his WORKS-in eight volumes octavo. Successively an assistant at Harrow, and the proprietor of an academy at Stanmore, he was at the basis a schoolmaster, although he spent the better part of his life as perpetual curate of Hatton, and even attained the dignity of a prebendal stall in St. Paul's. It is related of Parr, that, soon after setting up at Stanmore, he found himself in need of a wife. By some kind friends, a person thought to be a suitable partner was selected for him; but the union did not prove a happy one. It was remarked that he had wanted a housekeeper, and that the lady had wanted a house. She was of a good family in Yorkshire, an only child, who had been brought up by two maiden aunts, 'in rigidity and frigidity,' and she described her husband as having been 'born in a whirlwind, and bred a tyrant.' She was a clever woman and a voluble talker, and took a pleasure in exposing his foibles and peculiarities before company. At Stanmore Dr. Parr assumed the full-bottomed wig, which afterwards became a distinguishing part of his full dress. The Rev Sydney Smith has given a humorous description of this ornament of his person: 'Whoever has had the good fortune to see Dr. Parr's wig, must have observed, that while it trespasses a little on the orthodox magnitude of perukes in the anterior parts, it scorns even episcopal limits behind, and swells out into boundless convexity of frizz, the μέγα θαύα of barbers, and the terror of the literary world.' At Stanmore he abandoned himself to smoking, which became his habit through life. He would sometimes ride in prelatical pomp through the streets on a black saddle, bearing in his hand a long cane or wand, with an ivory head like a crosier. At other times he was seen stalking through the town in a dirty striped morning gown. In 1787 Dr. Parr published, in conjunction with his friend the Rev Henry Homer, a new edition of Bellendenus De Static. William Bellenden was a learned Scotchman, who was a Professor in the University of Paris, and wrote in Latin a work in three books, entitled De Static Primcipus, De Static Reipublicar, and De Static Prisci Orbis. The three books of this republication were dedicated respectively to Mr. Burke, Lord North, and Mr. Fox; and Dr. Parr prefixed a Latin Preface, exhibiting in high eulogistic relief the characters of those three statesmen, the 'Tria Lumina Anglorum.' The book was published anonymously, and excited the curiosity of the literary world. Parr anticipated the fame which his preface would confer upon him. His vanity was excessive, and so obvious as frequently to expose him to ridicule. If the different pas-sages of his letters, in which he has praised himself, were collected together, they would make a book; but the one which he wrote to Mr. Homer, when he had completed the Preface to Bellendeyuus, contains an outburst of self-conceit and self-laudation, which is probably without a parallel. As such it is worth transcribing: 'Dear Sir, what will you say, or rather, what shall I say myself, of myself? It is now ten o'clock at night, and I am smoking a quiet pipe, after a most vehement, and, I think, a most splendid effort of composition-an effort it was indeed, a mighty and a glorious effort; for the object of it is, to lift up Burke to the pinnacle where he ought to have been placed before, and to drag down Lord Chatham from that eminence to which the cowardice of his hearers, and the credulity of the public, had most weakly and most undeservedly exalted the impostor and father of impostors. Read it, dear Harry; read it, I say, aloud; read it again and again; and when your tongue has turned its edge from me to the father of Mr. Pitt, when your ears tingle and ring with my sonorous periods, when your heart glows and beats with the fond and triumphant remembrance of Edmund Burke-then, dear Homer, you will forgive me, you will love me, you will congratulate me, and readily will you take upon yourself the trouble of printing what in writing has cost me much greater though not longer trouble. Old boy, I tell you that no part of the Preface is better conceived, or better written; none will be read more eagerly, or felt by those whom you wish to feel it, more severely. Old boy, old boy, it is a stinger; and now to other business,' &c. Soon after the death of Mr. Fox, Dr. Parr announced his intention of publishing a life of the statesman whom he so much admired. The expectations of the public were disappointed by the publication, in 1809, of Characters of the late Charles James Fox, selected, and in part written, by Philopatris Varvicensis, two vols. 8vo. Of the first volume one hundred and seventy-five pages are extracted verbatim from public journals, periodical publications, speeches, and other sources; and of these characters the best is by Sir James Mackintosh; next, a panegyric on Mr. Fox by Dr. Parr himself occupies one hundred and thirty-five pages. The second volume is entirely occupied by notes upon a variety of topics which. the panegyric has suggested, such as the penal code, religious liberty, and others, plentifully inlaid with quotations from the learned languages. Dr. Parr's knowledge on ecclesiastical, political, and literary subjects, was extensive, and his conversation was copious and animated. He had a great reputation in his day as a table-talker, although his utterance was thick, and his manner overbearing, and often violent. Sydney Smith, several years after Dr. Parr's death, remarked, that 'he would have been a more considerable man if he had been more knocked about among equals. He lived with country gentlemen and clergymen, who flattered and feared him.' When he met with Dr. Johnson, who was more than his equal, at Mr. Langton's, as recorded in Boswell (Life, edited by Croker, royal Svo, p. 659), he was upon his good behaviour, and the Doctor praised him. 'Sir, I am much obliged to you for having asked me this evening. Parr is a fair man. I do not know when I have had an occasion of such free controversy. It is remarkable how much of a man's life may pass without meeting any instance of this kind of open discussion.' In the performance of his clerical duties Dr. Parr was assiduous; he was an advocate for more than the pomp and circumstance of the established forms of public worship. His wax candles were of unusual length and thickness, his communion-plate massive, and he decorated his church, at his own expense, with windows of painted glass. He had an extraordinary fondness for church-bells, and in order to furnish his belfry up to the height of his wishes he made many appeals to the liberality of his friends and correspondents. He himself writes, 'I have been importunate, and even impudent.' In one of his letters he intimates an intention of writing a work on Campanology; but even if he had done so, he would hardly have reached the height of enthusiasm of Joannes Barbricius, who, in his book, De Cielo et Ccelesti State, Mentz, 1618, employs four hundred and twenty-five pages to prove that the principal employment of the blessed in heaven will be the ringing of bells. His style, as a writer of English, is exceedingly artificial. Sydney Smith, in reviewing his Spital Sermon, preached in 1800, gives a description of it which is generally applicable to all his compositions. 'The Doctor is never simple and natural for a single moment. Everything smells of the rhetorician. He never appears to forget himself, or to be hurried by his subject into obvious language. Dr. Parr seems to think that eloquence consists not in an exuberance of beautiful images, not in simple and sublime conceptions, not in the feelings of the passions, but in a studious arrangement of sonorous, exotic, and sesquipedal words.' He had a very high opinion of himself as a writer of Latin epitaphs, of which he composed about thirty. At a dinner, when Lord Erskine had delighted the company with his conversation, Dr. Parr, in an ecstasy, called out to him, 'My Lord, I mean to write your epitaph.' Erskine, who was a younger man, replied, 'Dr. Parr, it is a temptation to commit suicide.' The epitaph on Dr. Johnson, inscribed on his monument in St. Paul's Cathedral, was written by Dr. Parr. At the end of the fourth volume of his works, is a long correspondence respecting this epitaph, between Parr, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Malone, and other friends of the deceased Doctor. The reader 'will be amused at the burlesque importance which. Parr attaches to epitaph-writing:- Croker. Dr. Parr's handwriting was very bad. Sir William Jones writes to him: 'To speak plainly with you, your English and Latin characters are so badly formed, that I have infinite difficulty to read your letters, and have abandoned all hopes of deciphering many of them. Your Greek is wholly illegible; it is perfect algebra.' TALMAThough Talma displayed in early boyhood a remarkable tendency to theatricals, his first attempt on a public stage, in 1783, was such as to cause his friends to discommend his pursuing the histrionic profession. It was not till a second attempt at the Theatre Francais (four years later) that he fixed the public approbation. On the retirement of Lavire, he became principal tragedian at that establishment; and no sooner was he launched in his career than his superior intellect began to work towards various reformations of the stage, particularly in the department of costume. He is said to have been the first in his own country who performed the part of Titus in a Roman toga. Talma was an early acquaintance of the first Napoleon, then Captain Buonaparte, to whom he was first introduced in the green-room of the Theatre Francais; and he used to relate that, about this time, Buonaparte, being in great pecuniary distress, had resolved to throw himself into the Seine, when he fortunately met with an old schoolfellow, who had just received a considerable sum of money, which he shared with the future emperor. 'If that warm-hearted comrade,' said he, 'had accidentally passed down another street, the history of the next twenty years would have been written without the names of Lodi, Marengo, Austerlitz, Jena, Friedland, Moscow, Leipsig, and Waterloo.' When his friend Buonaparte was setting out on his expedition to Egypt, the great tragedian offered, in the warmth of his friendship, to accompany him; but Napoleon would not listen to the proposal. 'Talma,' said he, 'you must not commit such an act of folly. You have a brilliant course before you; leave fighting to those who are unable to do anything better.' When Napoleon rose to he First Consul, his reception of Talma was as cordial as ever. When he in time became Emperor, the actor conceived that the intimacy would be sure to cease; but he soon received a special invitation to the Tuileries. Talma was a man of cultivated mind, unerring taste, and amiable qualities. 'His dignity and tragic powers on the stage,' says Lady Morgan, 'are curiously but charmingly contrasted with the simplicity, playfulness, and gaiety of his most unassuming, unpretending manners in private life.' He had long been married to a lady of fortune. He lived in affluence principally at his villa in the neighbourhood of Paris, whither, twice a week, he went to perform. Talma, when near his sixtieth year, achieved one of his greatest triumphs in Jouy's tragedy of Sylla. Napoleon had then (December, 1821) been dead only a few months. The actor, in order to recall the living image of his friend and patron, dressed his hair exactly after the well-remembered style of the deceased emperor, and his dictator's wreath was a facsimile of the laurel crown in gold which was placed upon Napoleon's brow at Notre Dame. The intended identity was recognised at once with great excitement. The government thought of interdicting the play; but Talma was privately directed to curl his hair in future, and adopt a new arrangement of the head. Talma was taken ill at Paris, where he expired without pain, 19th October 1826. His majestic features have been preserved to us by David in marble. The body was borne to the cemetery of Pere la Chaise, attended by at least 100,000 mourners; and his friend, comrade, and rival, Lafont, placed upon the coffin a wreath of immortelles, and pronounced an affectionate funeral oration.'-Cole's Life of Charles Kean. Talma was no less honoured and esteemed by Louis XVIII than by Napoleon. In 1825 he published some reflections on his favourite art; and, June 11, 1826, he appeared for the last time on the stage in the part of Charles VI. He is said altogether to have created seventy-one characters, the most popular of which were Orestes, OEdipus, Nero, Manlius, Caesar, China, Augustus, Coriolanus, Hector, Othello, Leicester, Sylla, Regulus, Leonidas, Charles VI, and Henry VIII. He spoke English perfectly; he was the friend and guest of John Kemble, and was present in Covent Garden Theatre, when that great actor took his leave of the stage. THE BURLESQUE ENGAGEMENTMany to the steep of Highgate die; Ask, ye Baeceotian shades! the reason why? 'Tis to the worship of the solemn Horn, Grasped in the holy hand of Mystery, In whose dread name both men and maids are sworn, And consecrate the oath with draught and dance till morn. The poet here alludes to a curious old custom which has been the means of giving a little gentle merriment to many generations of the citizens of London, but is now fallen entirely out of notice. It was localised at Highgate, a well-known village on the north road, about five miles from the centre of the metropolis, and usually the last place of stoppage for stage coaches on their way thither. Highgate has many villas of old date clustering about it, wealthy people having been attracted to the place on account of the fine air and beautiful views which it derives from its eminent site: Charles Mathews had his private box here; and Coleridge lived with Mr. Gillman in one of the Highgate terraces. The village, however, was most remarkable, forty years ago, and at earlier dates, for the extraordinary number of its inns and taverns, haunts of recreation-seeking Londoners, and partly deriving support from the numerous travellers who paused there on their way to town.  When Mr. William Hone was publishing his Every Day Book in 1826, he found there were no fewer than nineteen licensed houses of entertainment in this airy hamlet. The house of greatest dignity and largest accommodation was the Gate House, so called from the original building having been connected with a gate which here closed the road, and from which the name of the village is understood to have been derived. Another hostelry of old standing was 'The Bell.' There were also 'The Green Dragon,' 'The Bull,' 'The Angel,' 'The Crown,' 'The Flask,' &c. At every one of these public-houses there was kept a pair of horns, either ram's, bull's, or stag's, mounted on a stick, to serve in a burlesque ceremonial which time out of mind had been kept up at the taverns of Highgate, commonly called 'Swearing on the Horns.' It is believed that this custom took its rise at 'The Gatehouse,' and gradually spread to the other houses-perhaps was even to some extent a cause of other houses being set up, for it came in time to be an attraction for jovial parties from London. In some cases there was also a pair of mounted horns over the door of the house, as designed to give the chance passengers the assurance that the merry ceremonial was there practised. And the ceremonial-in what did it consist? Simply in this, that when any person passed through Highgate for the first time on his way to London, he, being brought before the horns at one of the taverns, had a mock oath administered to him, to the effect that he would never drink small beer when he could get strong, unless he liked it better; that he would never, except on similar grounds of choice, eat brown bread when he could get white, or water-gruel when he could command turtle-soup; that he would never make love to the maid when he might to the mistress, unless he preferred the maid; and so on with a number of things, regarding which the preferableness is equally obvious. Such at least was the bare substance of the affair; but of course there was room for a luxuriance of comicality, according to the wit of the imposer of the oath, and the simplicity of the oath-taker; and, as might be expected, the ceremony was not a dry one. Scarcely ever did a stage-coach stop at a Highgate tavern in those days, without a few of the passengers being initiated amidst the laughter of the rest, the landlord usually acting as high-priest on the occasion, while a waiter or an ostler would perform the duty of clerk, and sing out 'Amen' at all the proper places. Our artist has endeavoured to represent the ceremonial in the case of a simple countryman, according to the best traditionary lights that can now be had upon the subject. It is acknowledged that there were great differences in the ceremonial at different houses, some landlords having much greater command of wit than others. One who possessed the qualifications more eminently than the rest, would give an address warning the neophyte to avoid the allurements of the metropolis, in terms which provoked shouts of laughter from the bystanders. He would tell him-if, on his next coming to Highgate, he should see three pigs lying in a ditch, it was his privilege to kick the middle one out and take her place; if he wanted a bottle of wine and had no money, he might drink one on credit if anybody felt inclined to trust him. He would also be told, at the end of the oath, to kiss the horns, or any pretty girl in the company who would allow him. Another part of the jocularity was to tell him to take notice of the first word of the oath-he must be sure to mind that. If he forgot that, he would be liable to have to take the oath over again. That, in short, was a word to him of infinite importance, a forgetting of which could not fail to be attended with troublesome consequences. The privileges of Highgate had always to be paid for in some liquor for the company, according to the means and inclination of the person sworn. In those old unthinking days of merry England, societies and corporations and groups of work-people, who were admitting a new member or associate, would come out in a body to High-gate to have him duly sworn upon the Horns and enjoy an afternoon's merrymaking at his expense. If we can put faith in Byron, parties of young people of both sexes, under (it is to be hoped) proper superintendence, would dance away the night after an initiation at the Horns. Once a joke of that sort was established, it was wonderful what a great deal could be made of it, and how ill it was to wear out. For thirty years past, however, the Horns have disappeared from Highgate, and the taverns of that tidy village have now as grave an aspect as their neighbours. With regard to the origin of the custom in connexion with Highgate, it seems impossible to obtain any light. Most probably the custom was long ago not an uncommon one at favourite inns, and only survived at Highgate when it had gone out elsewhere. The only historical fact which has been preserved regarding it, is that a song embodying the burlesque oath was introduced in a pantomime at the Haymarket Theatre in 1742. BREAD, ITS MAKING AND SALE IN THE MIDDLE AGESIn the chronicles and records of the Middle Ages that have survived to us, we find many items of curious information relative to the supply in those days of what was, from the absence of the potato and other articles of food, even more than now, the staff of human life. We cull a few of these particulars for the information-and, we trust, also the amusement-of those among our readers who care to know something about the usages of the olden time. The bread that was in common use in England from five to six centuries ago, was of various degrees of fineness (or 'bolting, as it was called) and colour. The very finest and the whitest probably that was known, was simnel-bread, which (in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries at least) was as commonly known under the name of pain-demayn (afterwards corrupted into pay-man); a word which has given considerable trouble to Tyrrwhitt and other commentators upon Chaucer, but which means no more than 'bread of our Lord,' from the figure of our Saviour, or the Virgin Mary, impressed upon each round flat loaf, as is still the usage in Belgium with respect to certain rich cakes much admired there. This bread of course was only consumed by persons of the highest rank, and in the most affluent circumstances. The next in quality to this was wastel bread, in common use among the more luxurious and more wealthy of the middle classes, and the name of which it seems not improbable is closely allied to the old French gasteaw, 'a cake.' Nearly resembling this in price and quality, though at times somewhat cheaper, was light bread, or puffe, also known as ' French bread,' or 'cocket,' though why it was called by the latter appellation is matter of doubt. Bread of a still inferior quality was also sometimes known as 'cocket;' and it seems far from improbable that it was so called from the word cocket, as meaning a seal, it being a strict regulation in London and else-where that each loaf (at all events each loaf below a certain quality) should bear the impress of its baker's seal. The halfpenny loaf of simnel was at times of the same weight as the farthing loaf of wastel or puff; the relative proportions, however, varied considerably at different periods. The next class of bread was tourte, made of unbolted meal, and the name of which has much puzzled the learned. It seems not improbable, however, that this kind of bread was originally so called from the loaves having a twisted form (torti), to distinguish them from those of a finer quality. Tourte was in common use with the humbler classes and the inmates of monasteries. Trete bread, or bread of trete, was again an inferior bread to tourte, being made of wheat meal once bolted, or from which the fine flour at one sifting had been removed. This was also known as 'Us,' or brown bread, and probably owed its name to the fact of bran being so largely its constituent, that substance being still known in the North of England as 'trete'. An inferior bread to this seems to have passed under the name of all-sorts, or some similar appellation, being also known as black bread. It was made of various kinds of grain inferior to wheat. In the reign of Edward III we find mention made of a light, or French, bread, made in London (and resembling simnel probably), and known by the name of 'wygge,' an appellation still given in Scotland to a kind of small cake. Another kind of white bread is also spoken of in the reigns of Edward II and III, under the still well-known name of 'bunne' (or boun). Horse-bread also was extensively prepared by the bakers, in the form of loaves duly sealed, beans and peas being the principal ingredients employed. The profits of the bakers from very remote times were strictly a matter for legislatorial enactment. A general regulation was in force, from the days of King John until the reign of Edward I, if not later, throughout England (the City of London perhaps excepted), that the profit of the baker on each. quarter of wheat was to be, for his own labour, three pence and such bran as might be sifted from the meal; and that he was to add to the prime cost of the wheat, for fuel and wear of the oven, the price of two loaves; for the services of three men, he was to add to the price of the bread three halfpence; and for two boys one farthing; for the expenses attending the seal, one halfpenny; for yeast, one halfpenny; for candle, one halfpenny; for wood, threepence; and for wear and tear of the bolter, or bolting-sieve, one halfpenny. In London, only farthing loaves and halfpenny loaves were allowed to be made, and it was a serious offence, attended by forfeiture and punishment, for a baker to be found selling loaves of any other size. Loaves of this description seem to have been sometimes smuggled into market beneath a towel, or beneath the folds of the garments, under the arms. For the better identification of the latter, in case of necessity, each loaf was sealed with the baker's seal; and this from time to time, and at the Wardmotes more especially, was shewn to the alderman of the Ward, who exacted a fee for registering it in his book. In London, from time to time, at least once in the month, each baker's bread (or, at all events, some sample loaves) was taken from the oven by the officers of the assayers, who seem to have had the appellation of' 'hutch-reves,' and duly examined as to quality and weight; it being enacted, however, in favour of the baker, that the scrutiny should always be made while the bread was hot; the ' assay,' or sample loaves, which were given out to the bakers periodically for their guidance as to weight and quality, being delivered to them while hot. In the City of London, if the baker sold his bread himself by retail, he was particularly forbidden -for reasons apparently not easy now to be appreciated or ascertained-to sell it in his house, or before his house, or before the oven where it was baked; in fact, he was only to sell it in the 'King's Market,' and such market as was assigned to him, and not elsewhere; by which term apparently, in the fourteenth century, the markets of Eastcheap, Cornhill, and Westcheap were meant. The foreign baker, however, or non-freeman, was allowed to store his bread for a single night. In the market, the loaves were exposed for sale in panyers (bread-baskets), or in boxes or chests, in those days known as 'hutches;' the latter being more especially employed in the sale of tourte bread. The principal days for the sale of bread in the London markets seem to have been Tuesday and Saturday, though sale there on Sundays is also mentioned: in the days of Henry III and Edward I, the king's toll on each basket of bread was one halfpenny on week days, and three halfpence on Sundays. In other instances, we find bread delivered in London from house to house by regratresses, also called hucksters,' or female retailers. These dealers, on purchasing their bread from the bakers, were privileged by law to receive thirteen articles for twelve, such being apparently the limit of their legitimate profits; though it seems to have been the usage in London, at least at one period, for the baker to give to each regratress who dealt with. him sixpence every Monday morning, by way of estreme, or hansel-money, and threepence as curtesy or good-bye money, on delivery upon Friday of the last batch of the week; a practice, however, which was forbidden by the authorities -the bakers being also ordered not to give credit to these regratresses when known to be in debt to others, and not to take bread back from them when once it had become cold. No regratress was allowed to cross London Bridge, or to go out of the City, to buy bread for the purpose of retailing it. The baker of tourte bread was also forbidden to sell to a regratress in his shop, but only from his hutch, in the King's market. Though considerable favour was shewn to such bakers as were resident within the walls of the City, and though at times the introduction of foreign bread, as being 'adulterine ' or spurious, was strictly prohibited; still, in general, a large proportion of the London supply was brought from a distance, Stratford he Bow, Stepney (Stevenhethe), Bromley (Bremble) in Essex, Paddington, and Saint Albans being among the places which we find mentioned; the carriage being by horse or in carts, the loaves being packed in the latter (at least sometimes, and as to the coarser kinds) without baskets. Bread seems to have been brought from the villages of Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire, in barges known as 'scuts,' or 'scows.' We read that, occasionally, the country bakers contrived to undersell their London brethren by making the public gainers of two ounces in the penny-worth of bread. Against bread made in Southwark there appears to have been an extraordinary degree of prejudice, the reason on one occasion assigned being, 'because the bakers of Snthewerk are not amenable to the justice of the City.' A common piece of fraud with knavish bakers seems to have been the making of bread of pure quality on the outside and coarse within; a practice which was forbidden by enactment, it being equally forbidden to make loaves of bran, or purposely mixed with bran. The baker of white bread was on no account to make tourte or brown bread, and similar restrictions were put upon the 'tom-tar,' or baker of brown bread, as to the making of white. Tourte bread being made of unbolted meal, we find the tourte bakers of the City of London forbidden (in the reign of Richard II) to have a bolting-sieve in their possession, as also to sell flour to a cook-the latter enactment being evidently intended to insure the comparative fineness of their bread, by preventing them from subtracting the flour from the meal. Bakers within the City were forbidden to heat their ovens with fern, stubble, or straw; and in the reign of King John (A.D. 1212), in consequence of the recent devastation of the City by fire, they were not allowed to bake at night. They were also at times reminded by the civic authorities that it was their duty to instruct their servants so many times in the year, how to bolt the flour and knead their dough; and for the latter purpose they were not to use fountain-water, as being probably too hard. Hostelers and herbergeours (keepers of inns and lodging-houses) were not allowed to bake bread. Private individuals who had no ovens of their own, were in the habit of sending their flour to be kneaded by their own servants at the 'moulding-boards' belonging to the bakers, the loaves being then baked in the baker's oven. Persons of respectability also had the right to enter bake-houses to see the bread made. Bakers were allowed, in London, to keep swine in their houses at times when other persons were for-bidden, with a view probably to the more speedy consumption of the refuse bran, and as an inducement to the baker not to make his bread of too coarse a quality. The swine, however, were to be kept out of the public streets and lanes. No baker was allowed in the city to withdraw the servant or journeyman of another, nor was he to admit such a person into his service without a licence from the master whom he had previously served. The frauds and punishments of English bakers in bygone centuries, we may perhaps find an opportunity of making the subject of future investigation. |