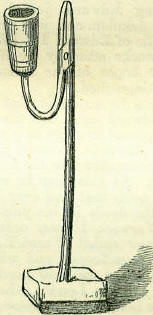

13th AprilBorn: Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, statesman, 1593, Chancery-lane, London; Jean Pierre Crousaz, Swiss divine, philosopher, and mathematician, 1663, Lausanne; Frederick North, Earl of Guildford, statesman, 1732; Philip Louis, Duke of Orleans, 1747, St. Cloud; Dr. Thomas Beddoes, writer on medicine and natural history, 1760. Died: Henry, Duke of Rohan, French military commander, 1638, Switzerland; Charles Leslie, controversialist, 1722, Glaslough; Christopher Pitt, translator of Virgil, 1748, Blandford; George Frederick Handel, musical composer, 1759; Dr. Charles Burney, musician, and author of History of Music, 1814, Chelsea; Captain Hugh Clapperton, traveller, 1827; Sir Henry de la Beche, geologist, 1855; Sydney Lady Morgan, miscellaneous writer, 1859, London. Feast Day: St. Hermengild, martyr, 586. St. Guinoch, of Scotland, 9th century. St. Caradoc, priest and martyr, 1124. SIR HENRY DE LA BECHEThe chief of the Geological Survey of England and Wales, who died at the too early age of fifty-nine, was one of those men who, using moderate faculties with diligence, and under the guidance of sound common sense, prove more serviceable as examples than the most brilliant geniuses. His natural destiny was the half-idle, self-indulgent life of a man of fortune; but his active mind being early attracted to the rising science of geology, he was saved for a better fate. With ceaseless assiduity he explored the surface of the south-western province of England, completing its survey in a great measure at his own expense. He employed intervals in composing works expository of the science, all marked by wonderful clearness and a strong practical bearing. Finally, when in office as chief of the survey, he was the means of founding a mineralogical museum and school in London, which has proved of the greatest service in promoting a knowledge of the science, and which forms the most suitable monument to his memory. THE EDICT OF NANTESWith a view to the conclusion of a series of troubles which had harassed his kingdom for several years, Henry IV of France came to an agreement with the Protestant section of his subjects, which was embodied in an edict, signed by him at Nantes, April 13th,1598. By it, Protestant lords de fief haut-justicier were entitled to have the full exercise of their religion in their houses; lords sans haute jacstiee could have thirty persons present at their devotions. The exercise of the Reformed religion was permitted in all places which were under the jurisdiction of a parliament. The Calvinists could, without any petition to superiors, print their books in all places where their religion was permitted [some parts of the kingdom were, in deference to particular treaties, exempted from the edict]. What was most important, Protestants were made competent for any office or dignity in the state. Considering the prejudices of the bulk of the French people, it is wonderful that the Protestants obtained so much on this occasion. After all, Henry was not able to get the edict registered till next year, when the Pope's legate had quitted the kingdom. [Revocation of the Edict of Nantes] KING CHARLES'S STATUE AT CHARING-CROSSThe bronze statue at Charing-cross has been the subject of more vicissitudes, and has attracted a larger amount of public attention, than is usual among our statues. In 1810, the newspapers announced that 'On Friday night (April 13th), the sword, buckler, and straps fell from the equestrian statue of King Charles the First at Charing-cross. The appendages, similar to the statue, are of copper [bronze?]. The sword, &c., were picked up by a man of the name of Moxon, a porter, belonging to the Golden Cross Hotel, who deposited them in the care of Mr. Eyre, trunk-maker, in whose possession they remain till that gentleman receives instructions from the Board of Green Cloth at St. James's Palace relative to their reinstatement.' Something stranger than this happened to the statue in earlier times. It may be here stated that this statue is regarded as one of the finest in London. It was the work of Hubert le Soeur, a pupil of the celebrated John of Bologna. Invited to this country by King Charles, he modelled and cast the statue for the Earl of Arundel, the enlightened collector of the Arundelian Marbles. The statue seems to have been placed at Charing-cross at once; for immediately after the death of the king, the Parliament ordered it to be taken down, broken to pieces, and sold. It was bought by a brazier in Holborn, named John River. The brazier having an eye for taste, or, possibly, an eye for his own future profit, contrived to evade one of the conditions of the bargain; the statue, instead of being broken up, was quietly buried uninjured in his garden, while some broken pieces of metal were produced as a blind to the Parliament. River was, unquestionably, a fellow alive to the tricks of trade; for he made a great number of bronze handles for knives and forks, and sold them as having been made from the fragments of the statue; they were bought by the loyalists as a mark of affection to the deceased king, and by the republicans as a memorial of their triumph. When Charles the Second returned, the statue was brought from its hiding-place, repurchased, and set up again at Charing-cross, where it was for a long time regarded as a kind of party memorial. While the scaffolding was up for its re-erection, Andrew Marvell wrote some sarcastic stanzas, of which the following was one: To comfort the heart of the poor Cavalier, The late King on horseback is here to be shewn. What ado with your kings and your statues is here! Have we not had enough, pray, already of one? About the year 1670, Sir Robert Vyner, merchant and Lord Mayor, set up an equestrian statue of Charles the Second at Stocks Market, the site of the present Mansion House; and as there was some reason to believe that Vyner had venal reasons for flattering the existing monarch, Andrew Marvell took advantage of the opportunity to make an onslaught on both the monarchs at once. He produced a rhymed dialogue for the two bronze horses: the Charing-cross horse reviled the profligacy of Charles the Second; while the Stocks Market horse retaliated by abusing Charles the First for his despotism. Among the bitter things said by the Charing-cross horse, was: That he should he styled Defender of the Faith, Who believes not a word what the Word of God saith! and Though he changed his religion, I hope he's so civil, Not to think his own father is gone to the devil! And when the Stocks Market horse launched out at Charles the First for having fought desperately for 'the surplice, lawn sleeves, the cross, and the mitre,' the Charing-cross horse retorted with a sneer: Thy king will ne'er fight unless for his queans. In much more recent days, the Charing-cross statue became an object of archaeological solicitude on other grounds. In Notes and Queries for 1850 (p. 18), Mr. Planché asked: When did the real sword of Charles the First's time, which but a few years back hung at the side of that monarch's equestrian figure at Charing-cross, disappear; and what has become of it? This question was put, at my suggestion, to the official authorities by the Secretary of the British Archaeological Association; but no information could be obtained on the subject. That the sword was a real one of that period, I state upon the authority of my learned friend, the late Sir Samuel Meyrick, who had ascertained the fact, and pointed out to me its loss. To this query Mr. Street shortly afterwards replied: The sword disappeared about the time of the coronation of her present majesty, when some scaffolding was erected about the statue, which afforded great facilities for removing the rapier (for such it was); and I always understood that it found its way, by some means or other, to the Museum (so called) of the notorious Captain D.; where, in company with the wand of the Great Wizard of the North, and other well-known articles, it was carefully labelled and numbered, and a little account appended of the circumstance of its acquisition and removal. The editor of Notes and Queries pointedly added: The age of chivalry is certainly past; otherwise the idea of disarming a statue would never have entered the head of any man of arms even in his most frolicsome of moods. We may conclude, then, that the present sword of this remarkable statue is a modern substitute. RUSHES AND RUSH-BEARINGIn ages long before the luxury of carpets was known in England, the floors of houses were covered with a much more homely material. When William the Conqueror invested his favourites with some of the Aylesbury lands, it was under the tenure of providing 'straw for his bed-chamber; three eels for his use in winter, and in summer straw, rushes, and two green geese thrice every year.' It is true that in the romance of Ywaine and Gavin, we read: When he unto chamber yede, The chamber fore, and als ye bede, With Mathes of gold were al over sprat; but even in the palaces of royalty the floors were generally strewed with rushes and straw, sometimes mixed with sweet herbs. In the household roll of Edward II we find an entry of money paid to John de Carleford, for going from York to Newcastle to procure straw for the king's chamber. Froissart, relating the death of Gaston, Count de Foix, says,-that the count went to his chamber, which he found ready strewed with rushes and green leaves, and the walls were hung with boughs newly cut for perfume and coolness, as the weather was marvellously hot. Adam Davie, Marshal of Stratford-le-bow, who wrote about the year 1312, in his poem of the Life of Alexander, describing the marriage of Cleopatra, says: Thee was many a blithe grome; Of olive, and of ruge floures, Worm y strewed halls and bowres; With samytes and bandekyns Weren curtayned the gardyns. This custom of strewing the 'halle and bowres' was continued to a much later period. Hentzner, in his Itinerary, says of Queen Elizabeth's presence chamber at Greenwich: 'The floor, after the English fashion, was strewed with hay,' meaning rushes. If, however, we may trust to an epistle, wherein Erasmus gives an account of this practice to his friend Dr. Francis, physician to Cardinal Wolsey, it would appear that, the rushes being seldom thoroughly changed, and the habits of those days not very cleanly, the smell soon became anything but pleasant. He speaks of the lowest layer of rushes (the top only being renewed) as remaining unchanged sometimes for twenty years; a receptacle for beer, grease, fragments of victuals, and other organic matters. To this filthiness he ascribes the frequent pestilences with which the people were afflicted, and Erasmus recommends the entire banishment of rushes, and a better ventilation, the sanitary importance of which was thus, we see, perceived more than two centuries since. When Henry III, King of France, demanded of Monsieur Dandelot what especial things he had noted in England during the time of his negotiation there, 'he answered that he had seen but three things remarkable; which were, that the people did drinke in bootee, eate rawe fish, and strewed all their best roomes with hay; meaning blacke jacks, oysters, and rushes.' ( Wits, Fits, and Fancies, 4to. 1614.) The English stage was strewed with rushes in Shakspeare's time; and the Globe Theatre was roofed with rushes, or as Taylor, the water-poet, describes it, the old theatre 'had a thatched hide,' and it was through the rushes in the roof taking fire that the first Globe Theatre was burnt down. Killigrew told Pepys how he had improved the stage from a time when there was 'nothing but rushes upon the ground, and everything else mean.' To the rushes succeeded matting; then for tragedy black hangings, after which came the green cloth still used-the cloth, as Goldsmith humorously observes, spread for bloody work. The strewing of rushes in the way where processions were to pass, is attributed by our poets to all times and countries. Thus, at the coronation of Henry V, when the procession is coming, the grooms cry: 'More rushes, more rushes!' Thus also at a wedding: Full many maids, clad in their best array, In honour of the bride, come with their fiaskets Fill'd full with flowers: others in wicker baskets Bring from the marish rushes, to o'erspread The ground, whereon to church the lovers tread. They were used green: Where is this stranger? Rushes, ladies, rushes, Rushes as green as summer for this stranger. Not worth a rush became a common comparison for anything worthless; the rush being of so little value as to be trodden under foot. Gower has: For til I se the daie springe, I sotto slepe nought at a rushed We find the rush used in Devonshire in a charm for the thrush, as follows: 'Take three rushes from any running stream, and pass them separately through the mouth of the intent, then plunge the rushes again into the stream, and as the current bears them away, so will the thrush depart from the child.'-Notes and Queries, No. 203. In the Herball to the Bible, 1587, mention is made of 'sedge and rushes, the whiche manie in the countrie doe use in sommer-time to strewe their parlors or churches, as well for coolness as for pleasant smell.' The species preferred was the Calamus aromaticus, which, when bruised, gives forth an odour resembling that of the myrtle; in the absence of this, inferior kinds were used. Provision was made for strewing the earthen or paved floors of churches with straw or rushes, according to the season of the year. We find several entries in parish accounts for this purpose. Brand quotes from the churchwardens' accounts of St. Mary-at-hill, London, of which parish he was rector: '1504. Paid for 2 Borden Rysshes for the strewing the newe pewes, 3d.' '1493. For 3 Burdens of rushes for ye new pews, 3d.'  We find also in the parish account-book of Hails-ham, in Sussex, charges for strewing the church floor with straw or rushes, according to the season of the year; and in the books of the city of Norwich, entries for pea-straw used for such strewing. The Rev. G. Miles Cooper, in his paper on the Abbey of Bayham, in the Sussex Archaeological Collections, vol. ix. 1857, observes: Though few are ignorant of this ancient custom, it may not perhaps be so generally known, that the strewing of churches grew into a religions festival, dressed up in all that picturesque circumstance where-with the old church well knew how to array its ritual. Remains of it linger to this day in remote parts of England. In Westmoreland, Lancashire, and districts of Yorkshire, there is still celebrated between hay-making and harvest a village fete called the Rush-bearing. Young women dressed in white, and carrying garlands of flowers and rushes, walk in procession to the parish church, accompanied by a crowd of rustics, with flags flying and music playing. There they suspend their floral chaplets on the chancel rails, and the day is concluded with a simple feast. The neighbourhood of Ambleside was, until lately, and may be still, one of the chief strongholds of this popular practice; respecting which I will only add, as a curious fact, that up to the passing of the recent Municipal Reform Act, the town clerk of Norwich was accustomed to pay to the subsacrist of the cathedral an annual guinea for strewing the floor of the cathedral with rushes on the Mayor's Day, from the western door to the entrance into the choir; this is the most recent instance of the ancient usage which has come to my knowledge. In Cheshire, at Runcorn, and Warburton, the annual rush-bearing wake is carried out in grand style. A large quantity of rushes-sometimes a cart-load is collected, and being bound on the cart, are cut evenly at each end, and on Saturday evening a number of men sit on the top of the rushes, holding garlands of artificial flowers, tinsel, &c. The cart is drawn round the parish by three or four spirited horses, decked with ribbons, the collars being surrounded with small bells. It is attended by morris-dancers fantastically dressed; there are men in women's clothes, one of whom, with his face blackened, has a belt with a large bell attached, round his waist, and carries a ladle to collect money from the spectators. The party stop and dance at the public-house in their way to the parish church, where the rushes are deposited, and the garlands are hung up, to remain till the next year.  The uses of the rush in domestic economy are worth notice. Rush-lights, or candles with rush wicks, are of the greatest antiquity; for we learn from Pliny that the Romans applied different kinds of rushes to a similar purpose, as making them into flambeaux and wax-candles for use at funerals. The earliest Irish candles were rushes dipped in grease and placed in lamps of oil; and they have been similarly used in many districts of England. Aubrey, writing about 1673, says that at Ockley, in Surrey, 'the people draw peeled rushes through melted grease, which yields a sufficient light for ordinary use, is very cheap and useful, and burnes long.' This economical practice was common till towards the close of the last century. There was a regular utensil for holding the rush in burning; of which an example is here presented. The Rev. Gilbert White has devoted one letter to 'this simple piece of domestic economy,' in his Natural History of Selborne. He tells us: The proper species is the common soft rush, found in most pastures by the sides of streams, and under hedges. Decayed labourers, women, and children, gather these rushes late in summer; as soon as they are cut, they must be flung into water, and kept there, otherwise they will dry and shrink, and the peel will not run. When peeled they must lie on the grass to be bleached, and take the dew for some nights, after which they are dried in the sun. Some address is required in dipping these rushes into the scalding fat or grease. The careful wife of an industrious Hampshire labourer obtains all her fat for nothing: for she saves the scummings of her bacon pot for this use; and if the grease abound with salt she causes the salt to precipitate to the bottom, by setting the scummings in a warm oven. Where hogs are not much in use, and especially by the sea-side, the coarse animal oils will come very cheap. A pound of common grease may be procured for fourpence; and about six pounds of grease will dip a pound of rushes, which cost one shilling, so that a pound of rushes ready for burning will cost three shillings. If men that keep bees will mix a little wax with the grease, it will give it a consistency, render it more cleanly, and make the rushes burn longer: mutton suet will have the same effect. A pound avoirdupois contains 1600 rashes; and supposing each to burn on an average but half-an-hour, then a poor man will purchase 1800 hours of light, a time exceeding thirty-three entire days, for three shillings. According to this account, each rush, before dipping, costs one thirty-third of a farthing, and one-eleventh afterwards. Thus a poor family will enjoy five and a-half hours of comfortable light for a farthing. An experienced old housekeeper assured Mr. White that one pound and a half of rushes completely supplied her family the year round, since working-people burn no candle in the long days, because they rise and go to bed by daylight. Little farmers use rushes in the short days both morning and evening, in the dairy and kitchen; but the very poor, who are always the worst economists, and therefore must continue very poor, buy a half-penny candle every evening, which in their blowing, open rooms, does not burn much longer than two hours. Thus, they have only two hours' light for their money, instead of eleven. |