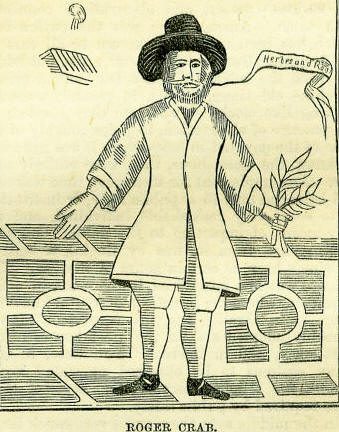

11th SeptemberBorn: Ulysses Aldrovandus, distinguished naturalist, 1522, Bologna; Henri, Vicomte de Turenne, great French commander, 1611, Sedan Castle on the Meuse; William Lowth, divine and commentator, 1661; James Thomson, poet, 1700, Ednam, Roxburghhshire. Died: Treasurer Cressingham, slain at battle of Stirling, 1297; James Harrington, author of Oceana, 1677, London; John Augustus Ernesti, classical editor, 1781, Leipsic; David Ricardo, political economist, 1823, Gatcombe Park, Gloucestershire; Captain Basil Hall, author of books of voyages and travels, 1844, Portsmouth. Feast Day: Saints Protus and Hyacinthus, martyrs. St. Paphnutius, bishop and confessor, 4th century. St. Patiens, arch-bishop of Lyon, confessor, about 480. THE TAKING OF DROGHEDA, SEPTEMBER 11, 1619In the summer following on the death of Charles I, Cromwell was sent into Ireland to bring it under obedience to the English parliament. The country was composed of factions-Catholics, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, &c. - agreeing in hardly anything but their opposition to the new Commonwealth. It was the policy of Cromwell to strike terror into these various parties by one thunderbolt of vigorous action and his assault upon the town of Drogheda afforded him the opportunity. There were here about 3000 royalists assembled under Sir Arthur Ashton. The town had some tolerably strong defences. Cromwell, on the 10th of September, summoned the town, but was answered only with a defiance. He set his cannon a-playing on the walls, and, having made some breaches, sent in a large armed force next day, who, however, were for that time repulsed. Renewing the assault, they drove the garrison into confined places, where the whole were that evening put to the sword, with merely a trifling exception. Cromwell, in his dispatch to Lenthall, describes this affair as a 'righteous judgment' and a 'great mercy,' and with equal coolness relates how any that he spared from death were immediately shipped off for Barbadoes-that is, deported as slaves. The policy of the English Attila was successful. It cut through the heart of the national resistance, and laid Ireland at the feet of the English parliament. ROGER CRAB Among the many crazy sectaries produced from the yeasty froth of the fermenting caldron of the great civil war, there was not one more oddly crazy than Roger Crab. This man had served for seven years in the Parliamentary army, and though he had his 'skull cloven' by a royalist trooper, yet, for some breach of discipline, Cromwell sentenced him to death, a punishment subsequently commuted to two years' imprisonment. After his release from jail, Crab set up in business as 'a haberdasher of hats' at Chesham, in Buckinghamshire. His wandering mind, probably not improved by the skull-cleaving operation, then imbibed the idea, that it was sinful to eat any kind of animal food, or to drink anything stronger than water. Determined to follow, literally, the injunctions given to the young man in the gospel, he sold off his stock in trade, distributing the proceeds among the poor, and took up his residence in a hut, situated on a rood of ground near Ickenham, where for some time he lived on. the small sum of three-farthings a week. His food consisted of bran, dock-leaves, mallows, and grass; and how it agreed with him we learn from a rare pamphlet, principally written by himself, entitled The English Hermit, or the Wonder of the Age. 'Instead of strong drinks and wines,' says the eccentric Roger, I give the old man a cup of water; and instead of roast mutton and rabbit, and other dainty dishes, I give him broth thickened with bran, and pudding made with bran and turnip-leaves chopped together, at which the old man (meaning my body) being moved, would know what he had done, that I used him so hardly. Then I shewed him his transgressions, and so the wars began. The law of the old man in my fleshly members rebelled against the law of my mind, and had a shrewd skirmish; but the mind, being well enlightened, held it so that the old man grew sick and weak with the flux, like to fall to the dust. But the wonderful love of God, well pleased with the battle, raised him up again, and filled him full of love, peace, and content of mind, and he is now become more humble, for now he will eat dock-leaves, mallows, or grass.' The persecutions the poor man inflicted on himself, caused him to be persecuted by others. Though he states that he was neither a Quaker, a Shaker, nor a Ranter, he was cudgelled and put in the stocks; the wretched sackcloth frock he wore was torn from his back, and he was mercilessly whipped. He was four times arrested on suspicion of being a wizard, and he was sent from prison to prison; yet still he would persist in his course of life, not hesitating to term all those whose opinion differed from his by the most opprobrious names. He published another pamphlet, entitled Dagon's Downfall; or the great Idol digged up Root and Branch; The English Hermit's Spade at the Ground and Root of Idolatry. This work shews that the man was simply insane. We last hear of him residing in Bethnal Green. He died on the 11th of September 1680, and was buried in Stepney Churchyard, where his tombstone exhibits the following quaint epitaph: Tread gently, reader, near the dust Committed to this tomb-stone's trust: For while 'twas flesh, it held a guest With universal love possest: A soul that stemmed opinion's tide, Did over sects in triumph ride; Yet separate from the giddy crowd, And paths tradition had allowed. Through good and ill reports he past, Oft censured, yet approved at last. Wouldst thou his religion know? In brief 'twas this: to all to do Just as he would be done unto. So in kind Nature's law he stood, A temple, undefiled with blood, A friend to everything that 's good. The rest angels alone can fitly tell; Haste then to them and him; and so farewell! |