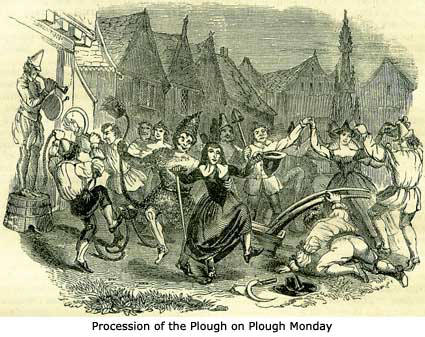

11th JanuaryBorn: Francesco Mazzuoli Parmigiano, painter, Parma, 1503; Henry Duke of Norfolk, 1654. Died: Sir Hans Sloane, M.D., 1753; Francois Roubiliac, sculptor, 1762; Dominic Cimarosa, musician, 1801; F. Schlegel, German critic, 1829. Feast Day: St. Hyginus, pope and martyr, 142. St. Theodosius, the Cænobiarch, 529. St. Salvius or Sauve, bishop of Amiens, 7th century. St. Egwin, bishop, confessor, 717. ST. THEODOSIUS, THE CÆNOBIARCHSt. Theodosius died in 529, at the age of 104. He was a native of Cappadocia, but when a young man removed to Jerusalem, in the vicinity of which city he resided during the remainder of his life. He is said to have lived for about thirty years as a hermit, in a cave, but having been joined by other saintly persons, he finally established a monastic community not far from Bethlehem. He was enabled to erect a suitable building, to which by degrees he added churches, infirmaries, and houses for the reception of strangers. The monks of Palestine at that period were called Cænobites; and Sallustius, bishop of Jerusalem, having appointed Theodosius superintendent of the monasteries, he received the name of Cænobiarch. He was banished by the Emperor Anastasius about the year 513, in consequence of his opposition to the Eutychian heresy, but was recalled by the Emperor Justinus. 'The first lesson which he taught his monks was, that the continual remembrance of death is the foundation of religious perfection; to imprint this more deeply in their minds, he caused a great grave or pit to be dug, which might serve for the common burial-place of the whole community, that by the presence of this memorial of death, and by continually meditating on that object, they might more perfectly learn to die daily. The burial-place being made, the abbot one day, when he had led his monks to it, said: 'The grave is made; who will first perform the dedication?' Basil, a priest, who was one of the number, falling on his knees, said to St. Theodosius: 'I am the person; be pleased to give me your blessing.' The abbot ordered the prayers of the Church for the dead to be offered up for him, and on the fortieth day, Basil wonderfully departed to our Lord in peace, without any apparent sickness. It may not be superfluous, in all reverence, to remark that, while a remembrance of our mortality is an essential part of religion, it is not necessary to be continually thinking on that subject. Life has active duties calling for a different exercise of our thoughts from day to day and throughout the hours of the day, and which would necessarily be neglected if we were to be obedient to the mandate of the Cænobiarch. Generally, our activity depends on the hopes of living, not on our expectation of dying; and perhaps it would not be very difficult to shew that the fact of our not being naturally disposed to dwell on the idea of an end to life, is one to be grateful for to the Author of the Universe, seeing that not merely our happiness, but in some degree our virtues, depend upon it. HENRY DUKE OF NORFOLKMr. E. Browne (son of Sir Thomas Browne) tells us in his journal (Sloane MSS.) of the celebration of the birthday of Mr. Henry Howard (afterwards Duke of Norfolk) at Norwich, January 11, 1664, when they kept up the dance till two o'clock in the morning. The festivities at Christmas, in the ducal palace there, are also described by Mr. Browne, and we get an idea from them of the extravagant merry-makings which the national joy at the Restoration had made fashionable. 'They had dancing every night, and gave entertainments to all that would come; he built up a room on purpose to dance in, very large, and hung with the bravest hangings I ever saw; his candlesticks, snuffers, tongs, fire-shovels, and andirons, were silver; a banquet was given every night after dancing; and three coaches were employed to fetch ladies every afternoon, the greatest of which would hold fourteen persons, and cost five hundred pound, without the harness, which cost six score more. 'January 5, Tuesday. I dined with Mr. Howard, where we drank out of pure gold, and had the music all the while, with the like, answerable to the grandeur of [so] noble a per-son: this night I danc'd with him also. 'January 6. I dined at my aunt Bendish's, and made an end of Christmas, at the duke's palace, with dancing at night, and a great banquet. His gates were open'd, and such a number of people flock'd in, that all the beer they could set out in the streets could not divert the stream of the multitudes, till very late at night.' SIR HANS SLOANESir Hans Sloane, Bart., the eminent physician and naturalist, from whose collections originated the British Museum, born at Killeleagh, in the north of Ireland, April 16, 1660, but of Scotch extraction-his father having been the head of a colony of Scots settled in Ulster under James I-gives us something like the model of a life perfectly useful in proportion to powers and opportunities. Having studied medicine and natural history, he settled in London in 1684, and was soon after elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, to which he presented some curiosities. In 1687 he was chosen a Fellow of the College of Physicians, and in the same year sailed for Jamaica, and remained there sixteen months, when he returned with a collection of 800 species of plants, and commenced publishing a Natural History of Jamaica, the second volume of which did not appear until nearly twenty years subsequent to the first; his collections in natural history, &c., then comprising 8,226 specimens in botany alone, besides 200 volumes of dried samples of plants. In 1716 George I created Sloane a baronet-a title to which no English physician had before attained. In 1719 he was elected President of the College of Physicians, which office he held for sixteen years; and in 1727 he was elected President of the Royal Society. He zealously exercised all his official duties until the age of fourscore. He then retired to an estate which he had purchased at Chelsea, where he continued to receive the visits of scientific men, of learned foreigners, and of the Royal Family; and he never refused admittance nor advice to rich or poor, though he was so infirm as but rarely to take a little air in his garden in a wheeled chair. He died after a short illness, bequeathing his museum to the public, on condition that £20,000 should be paid to his family; which sum scarcely exceeded the intrinsic value of the gold and silver medals, and the ores and precious stones in his collection, which he declares, in his will, cost at least £50,000. His library, consisting of 3,556 manuscripts and 50,000 volumes, was included in the bequest. Parliament accepted the trust on the required conditions, and thus Sloane's collections formed the nucleus of the British Museum. Sir Hans Sloane was a generous public benefactor. He devoted to charitable purposes every shilling of his thirty years' salary as physician to Christ's Hospital; he greatly assisted to establish the Dispensary set on foot by the College of Physicians; and he presented the Apothecaries' Company with the freehold of their Botanic Gardens at Chelsea. Sloane also aided in the formation of the Foundling Hospital. His remains rest in the churchyard of St. Luke's, by the river-side, Chelsea, where his monument has an urn entwined with serpents. His life was protracted by extraordinary means: when a youth he was attacked by spitting of blood, which interrupted his education for three years; but by abstinence from wine and other stimulants, and continuing, in some measure, this regimen ever afterwards, he was enabled to prolong his life to the age of ninety-three years; exemplifying the truth of his favourite maxim-that sobriety, emperance, and moderation are the best preservatives that nature has granted to mankind. Sir Hans Sloane was noted for his hospitality, but there were three things he never had at his table-salmon, champagne, and burgundy. LOTTERIESThe first lottery in England, as far as is ascertained, began to be drawn on the 11th of January, 1569, at the west door of St. Paul's Cathedral, and continued day and night till the 6th of May. The scheme, which had been announced two years before, shews that the lottery consisted of forty thousand lots or shares, at ten shillings each, and that it comprehended 'a great number of good prizes, as well of ready money as of plate, and certain sorts of merchandize.' The object of any profit that might arise from the scheme was the reparation of harbours and other useful public works. Lotteries did not take their origin in England; they were known in Italy at an earlier date; but from the year above named, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, down to 1826, (excepting for a short time following upon an Act of Queen Anne,) they continued to be adopted by the English government, as a source of revenue. It seems strange that so glaringly immoral a project should have been kept up with such sanction so long. The younger people at the present day may be at a loss to believe that, in the days of their fathers, there were large and imposing offices in London, and pretentious agencies in the provinces, for the sale of lottery tickets; while flaming advertisements on walls, in new books, and in the public journals, proclaimed the preferableness of such and such 'lucky' offices-this one having sold two-sixteenths of the last twenty thousand pounds prize; that one a half of the same; another having sold an entire thirty thousand pound ticket the year before; and so on. It was found possible to persuade the public, or a portion of it, that where a blessing had once lighted it was the more likely to light again. The State lottery was framed on the simple principle, that the State held forth a certain sum to be repaid by a larger. The transaction was usually managed thus. The government gave £10 in prizes for every share taken, on an average. A great many blanks, or of prizes under £10, left, of course, a surplus for the creation of a few magnificent prizes wherewith to attract the unwary public. Certain firms in the city, known as lottery-office-keepers, contracted for the lottery, each taking a certain number of shares the sum paid by them was always more than £10 per share; and the excess constituted the government profit. It was customary, for many years, for the con-tractors to give about £16 to the government, and then to charge the public from £20 to £22. It was made lawful for the contractors to divide the shares into halves, quarters, eighths, and sixteenths; and the contractors always charged relatively more for these aliquot parts. A man with thirty shillings to spare could buy a sixteenth; and the contractors made a large portion of their profit out of such customers. The government sometimes paid the prizes in terminable annuities instead of cash; and the loan system and the lottery system were occasionally combined in a very odd way. Thus, in 1780, every subscriber of £1000 towards a loan of £12,000,000, at four per cent., received a bonus of four lottery tickets, the value of each of which was £10, and any one of which might be the fortunate number for a twenty or thirty thousand pounds prize. Amongst the lottery offices, the competition for business was intense. One firm, finding an old woman in the country named Goodluck, gave her fifty pounds a year on condition that she would join them as a nominal partner, for the sake of the attractive effect of her name. In their advertisements each was sedulous to tell how many of the grand prizes had in former years fallen to the lot of persons who had bought at his shop. Woodcuts and copies of verses were abundant, suited to attract the uneducated. Lotteries, by creating illusive hopes, and supplanting steady industry, wrought immense mischief. Shopmen robbed their masters, servant girls their mistresses, friends borrowed from each other under false pretences, and husbands stinted their wives and children of necessaries-all to raise the means for buying a portion or the whole of a lottery ticket. But, although the humble and ignorant were the chief purchasers, there were many others who ought to have known better. In the interval between the purchase of a ticket and the drawing of the lottery, the speculators were in a state of unhealthy excitement. On one occasion a fraudulent dealer managed to sell the same ticket to two persons; it came up a five hundred pound prize; and one of the two went raving mad when he found that the real ticket was, after all, not held by him. On one occasion circumstances excited the public to such a degree that extravagant biddings were made for the few remaining shares in the lottery of that year, until at length one hundred and twenty guineas were given for a ticket on the day before the drawing, One particular year was marked by a singular incident: a lottery ticket was given to a child unborn, and was drawn a prize of one thousand pounds on the day after his birth. In 1767 a lady residing in Holborn had a lottery ticket presented to her by her husband; and on the Sunday preceding the drawing her success was prayed for in the parish church, in this form: 'The prayers of this congregation are desired for the success of a person engaged in a new under-taking.' In the same year the prize (or a prize) of twenty thousand pounds fell to the lot of a tavern-keeper at Abingdon. We are told, in the journals of the time- 'The broker who went from town to carry him the news he complimented with one hundred pounds. All the bells in the town were set a ringing. He called in his neighbours, and promised to assist this with a capital sum, that with another; gave away plenty of liquor, and vowed to lend a poor cobbler money to buy leather to stock his stall so full that he should not be able to get into it to work; and lastly, he promised to buy a new coach for the coachman who brought him down the ticket, and to give a set of as good horses as could be bought for money.' The theory of 'lucky numbers' was in great favour in the days of lotteries. At the drawing, papers were put into a hollow wheel, inscribed with as many different numbers as there were shares or tickets; one of these was drawn out (usually by a Blue-coat boy, who had a holiday and a present on such occasions), and the number audibly announced; another Blue-coat boy then drew out of another wheel a paper denoting either 'blank' or a 'prize' for a certain sum of money; and the purchaser of that particular number was awarded a blank or a prize accordingly. With a view to lucky numbers, one man would select his own age, or the age of his wife; another would select the date of the year; another a row of odd or of even numbers. Persons who went to rest with their thoughts full of lottery tickets were very likely to dream of some one or more numbers, and such dreams had a fearful influence on the waiters on the following morning. The readers of the Spectator will remember an amusing paper (No. 191, Oct. 9th, 1711), in which the subject of lucky numbers is treated in a manner pleasantly combining banter with useful caution. The man who selected 1711 because it was the year of our Lord; the other who sought for 134, because it constituted the minority on a celebrated bill in the House of Commons; the third who selected the 'mark of the Beast,' 666, on the ground that wicked beings are often lucky -these may or may not have been real instances quoted by the Spectator, but they serve well as types of classes. One lady, in 1790, bought No. 17090, because she thought it was the nearest in sound to 1790, which was already sold to some other applicant. On one occasion a tradesman bought four tickets, consecutive in numbers: he thought it foolish to have them so close together, and took one back to the office to be exchanged; the one thus taken back turned up a twenty thousand pounds prize! The lottery mania brought other evils in its train. A species of gambling sprang up, resembling time-bargains on the Stock Exchange; in which two persons, A and B, lay a wager as to the price of Consols at some future day; neither intend to buy or to sell, although nominally they treat for £10,000 or £100,000 of stock. So in the lottery days; men who did not possess tickets nevertheless lost or won by the failure or success of particular numbers, through a species of insurance which was in effect gambling. The matter was reduced almost to a mathematical science, or to an application of the theory of probabilities. Treatises and Essays, Tables and Calculations, were published for the benefit of the speculators. One of them, Painter's Guide to the Lottery, published in 1787, had a very long title-page, of which the following is only a part: The whole business of Insuring Tickets in the State Lottery clearly explained; the several advantages taken by the office keepers pointed out; an easy method given, whereby any person may compute the Probability of his Success upon purchasing or insuring any particular number of tickets; with a Table of the prices of Insurance for every day's drawing in the ensuing Lottery; and another Table, containing the number of tickets a person ought to purchase to make it an equal chance to have any particular prize.' PLOUGH MONDAYThis being In 1864 the first Monday after Twelfth Day, is for the year Plough Monday. Such was the name of a rustic festival, heretofore of great account in England, bearing in its first aspect, like St. Distaff's Day, reference to the resumption of labour after the Christmas holidays. In Catholic times, the ploughmen kept lights burning before certain images in churches, to obtain a blessing on their work; and they were accustomed on this day to go about in procession, gathering money for the support of these plough-lights, as they were called. The Reformation put out the lights; but it could not extinguish the festival. The peasantry contrived to go about in procession, collecting money, though only to be spent in conviviality in the public-house. It was at no remote date a very gay and rather pleasant-looking affair. A plough was dressed up with ribbons and other decorations-the Fool Plough. Thirty or forty stalwart swains, with their shirts over their jackets, and their shoulders and hats flaming with ribbons, dragged it along from house to house, preceded by one in the dress of an old woman, but much bedizened, bearing the name of Bessy. There was also a Fool, in fantastic attire. In some parts of the country, morrisdancers attended the procession; occasionally, too, some reproduction of the ancient Scandinavian sword-dance added to the means of persuading money out of the pockets of the lieges. A Correspondent, who has borne a part (cow-horn blowing) on many a Plough Monday in Lincolnshire, thus describes what happened on these occasions under his own observation: -Rude though it was, the Plough procession threw a life into the dreary scenery of winter, as it came winding along the quiet rutted lanes, on its way from one village to another; for the ploughmen from many a surrounding thorpe, hamlet, and lonely farm-house united in the celebration of Plough Monday. It was nothing unusual for at least a score of the 'sons of the soil' to yoke themselves with ropes to the plough, having put on clean smock-frocks in honour of the day. There was no limit to the number who joined in the morris-dance, and were partners with ' ossy,' who carried the money-box; and all these had ribbons in their hats and pinned about them wherever there was room to display a bunch. Many a hardworking country Molly lent a helping hand in decorating out her Johnny for Plough Monday, and finished him with an admiring exclamation of-'Lawks, John! thou does look smart, surely.' Some also wore small bunches of corn in their hats, from which the wheat was soon shaken out by the ungainly jumping which they called dancing. Occasionally, if the winter was severe, the procession was joined by threshers carrying their flails, reapers bearing their sickles, and carters with their long whips, which they were ever cracking to add to the noise, while even the smith and the miller were among the number, for the one sharpened the plough-shares and the other ground the corn; and Bessy rattled his box and danced so high. that he shewed his worsted stockings and corduroy breeches; and very often, if there was a thaw, tucked up his gown skirts under his waistcoat, and shook the bonnet off his head, and disarranged the long ringlets that ought to have concealed his whiskers. For Betsy is to the procession of Plough Monday what the leading figurante is to an opera or ballet, and dances about as gracefully as the hippopotami described by Dr Livingstone. But these rough antics were the cause of much laughter, and rarely do we ever remember hearing any coarse jest that would call up the angry blush to a modest cheek. No doubt they were called 'plough bullocks,' through drawing the plough, as bullocks were formerly used, and are still yoked to the plough in some parts of the country. The rubbishy verses they recited are not worth preserving beyond the line which graces many a public-house sign of 'God speed the plough.' At the large farm-house, besides money they obtained refreshment, and through the quantity of ale they thus drank during the day, managed to get what they called 'their load' by night. Even the poorest cottagers dropped a few pence into Bessy's box. But the great event of the day was when they came before some house which bore signs that the owner was well-to-do in the world, and nothing was given to them. Bossy rattled his box and the ploughmen danced, while the country lads blew their bullocks' horns, or shouted with all their might; but if there was still no sign, no coming forth of either bread-and-cheese or ale, then the word was given, the ploughshare driven into the ground before the door or window, the whole twenty men yoked pulling like one, and in a minute or two the ground before the house was as brown, barren, and ridgy as a newly-ploughed field. But this was rarely done, for everybody gave something, and were it but little the men never murmured, though they might talk about the stinginess of the giver afterwards amongst themselves, more especially if the party was what they called ' well off in the world.' We are notaware that the ploughmen were ever summoned to answer for such a breach of the law, for they believe, to use their own expressive language, ' they can stand by it, and no law in the world can touch 'em,' cause it's an old charter;' and we are sure it would spoil their ' folly to be wise.' One of the mummers generally wears a fox's skin in the form of a hood; but beyond the laughter the tail that hangs down his back awakens by its motion as he dances, we are at a loss to find a meaning. Bessy formerly wore a bullock's tail behind, under his gown, and which he held in his hand while dancing, but that appendage has not been worn of late. Some writers believe it is called White Plough Monday on account of the mummers having worn their shirts outside their other garments. This they may have done to set off the gaudy-coloured ribbons; though a clean white smock frock, such as they are accustomed to wear, would shew off their gay decorations quite as well. The shirts so worn we have never seen. Others have stated that Plough Monday has its origin from ploughing again commencing at this season. But this is rarely the case, as the ground is generally too hard, and the ploughing is either done in autumn, or is rarely begun until February, and very often not until the March sun has warmed and softened the ground. Some again argue that Plough Monday is a festival held in remembrance of ' the plough. having ceased from its labour.' After weighing all these arguments, we have come to the conclusion that the true light in which to look at the origin of this ancient custom is that thrown upon the subject by the ploughman's candle, burnt in the church at the shrine of' some saint, and that to maintain this light contributions were collected and sanctioned by the Church, and that the priests were the originators of Plough Monday.'  At Whitby, in Yorkshire, according to its historian, the Rev. G. Young, there was usually an extra band of six to dance the sword-dance. With one or more musicians to give them music on the violin or flute, they first arranged them-selves in a ring with their swords raised in the air. Then they went through a series of evolutions, at first slow and simple, afterwards more rapid and complicated, but always graceful. Towards the close each one catches the point of his neighbour's sword, and various movements take place in consequence; one of which consists in joining or plaiting the swords into the form of an elegant hexagon or rose, in the centre of the ring, which rose is so firmly made that one of them holds it up above their heads without undoing it. The dance closes with taking it to pieces, each man laying hold of his own sword. During the dance, two or three of the company called Toms or Clowns, dressed up as harlequins, in most fantastic modes, having their faces painted or masked, are making antic gestures to amuse the spectators; while another set called Madgies or Madryy Pegs, clumsily dressed in women's clothes, and also masked or painted, go from door to door rattling old canisters, in which they receive money. Where they are well paid they raise a huzza; where they get nothing, they shout ' hunger and starvation!' ' Domestic life in old times, however rude and comfortless compared with what it now is, or may be, was relieved by many little jocularities and traits of festive feeling. When the day came for the renewal of labour in earnest, there was a sort of competition between the maids and the men which should be most prompt in rising to work. If the ploughmen were up and dressed at the fire-side, with some of their field implements in hand, before the maids could get the kettle on, the latter party had to furnish a cock for the men next Shrovetide. As an alternative upon this statute, if any of the ploughmen, returning at night, came to the kitchen hatch, and cried 'Cock in the pot,' before any maid could cry 'Cock on the dunghill!' she incurred the same forfeit. DUTIES OF A DAY IN JANUARY FOR A PLOUGHMAN IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURYGervase Markham gives an account of these in his Farewell to Husbandry, 1653; and he starts with an allusion to the popular festival now under notice. 'We will,' says he, 'suppose it to be after Christmas, or about Plow Day, (which is the first setting out of the plow,) and at what time men either begin to fallow, or to break up pease-earth, which is to lie to bait, according to the custom of the country. At this time the Plow-man shall rise before four o'clock in the morning, and after thanks given to God for his rest, and the success of his labours, he shall go into his stable or beast-house, and first he shall fodder his cattle, then clean the house, and make the booths [stalls?] clean; rub down the cattle, and cleanse their skins from all filth. Then he shall curry his horses, rub them with cloths and wisps, and make both them and the stable as clean as may be. Then he shall water both his oxen and horses, and housing them again, give them more fodder and to his horse by all means provender, as chaff and dry pease or beans, or oat-hulls, or clean garbage (which is the hinder ends of any grain but rye), with the straw chopped small amongst it, according as the ability of the husbandman is. 'And while they are eating their meat, he shall make ready his collars, hames, treats, halters, mullers, and plow-gears, seeing everything fit and in its due place, and to these labours I will also allow two hours; that is, from four of the clock till six. Then he shall come in to breakfast, and to that I allow him half an hour, and then another half hour to the yoking and gearing of his cattle, so that at seven he may set forth to his labours; and then he shall plow from seven o'clock in the morning till betwixt two and three in the afternoon. Then he shall unyoke and bring home his cattle, and having rubbed them, dressed them, and cleansed them from all dirt and filth, he shall fodder them and give them meat. Then shall the servants go in to their dinner, which allowed half an hour, it will then be towards four of the clock; at what time he shall go to his cattle again, and rubbing them down and cleansing their stalls, give them more fodder; which done, he shall go into the barns, and provide and make ready fodder of all kinds for the next day. 'This being done, and carried into the stable, ox-house, or other convenient place, he shall then go water his cattle, and give them more meat, and to his horse provender; and by this time it will draw past six o'clock; at what time he shall come in to supper, and after supper he shall either sit by the fireside, mend shoes both for himself and their family, or beat and knock hemp or flax, or pick and stamp apples or crabs for eider or vinegar, or else grind malt on the querns, pick candle rushes, or do some husbandly office till it be fully eight o'clock. Then shall he take his lanthorn and candle, and go see his cattle, and having cleansed his stalls and planks, litter them down, look that they are safely tied, and then fodder and give them meat for all night. Then, giving God thanks for benefits received that day, let him and the whole household go to their rest till the next morning.' It is rather surprising to find the quern, the hand-mill of Scripture, continuing in use in England so late as the time of the Commonwealth, though only for the grinding of malt. It is now obsolete even in the Highlands, but is still used in the Faroe Islands. The stone mill of Bible times appears to have been driven by two women; but in Western Europe it was fashioned to be driven by one only, sometimes by a fixed handle, and sometimes by a moveable stick inserted in a hole in the circumference. |