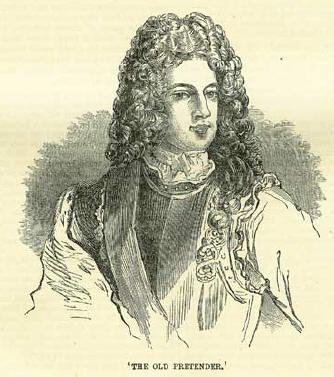

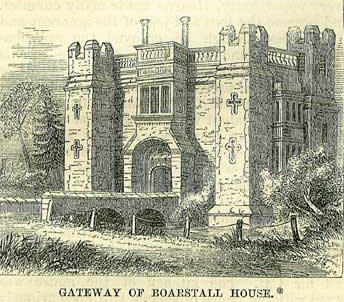

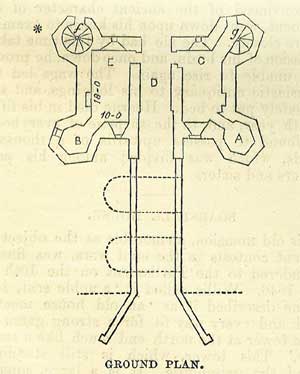

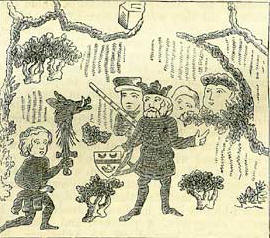

10th JuneBorn: James, Prince of Wales, commonly called 'the Pretender,' 1688, London; John Dollond, eminent optician, 1706, Spitalfields; James Short, maker of reflecting telescopes, 1710, Edinburgh. Died: Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, 1190, Cilicia; Thomas Hearne, antiquary, 1735, Oxford; James Smith, promoter of subsoil ploughing, 1850, Kinzeancleuch, Aprshire. Feast Day: Saints Getulius and companions, martyrs, 2nd century. St. Landry, or Landericus, Bishop of Paris, confessor, 7th century. St. Margaret, Queen of Scotland, 1093. Blessed Henry, or Rigo of Treviso, confessor, 1315. BIRTH OF JAMES PRINCE OF WALES The 10th [June 1688], being Trinity Sunday, between nine and ten in the morning, fifteen minutes before ten, the queen was delivered of a prince at St. James's, by Mrs. Wilkins the midwife, to whom the king gave 500 guineas for her paines: tis said the queen was very quick, so that few persons were by. As soon as known, the cannon at the Tower were discharged, and at night bonefires and ringing of bells were in several places.'-Luttrell's Brief Relation of State Affairs. It is the fate of many human beings to receive the reverse of a welcome on their introduction into the world; but seldom has an infant been so unwelcome, or to so large a body of people, as this poor little Prince of Wales. To his parents, indeed, his birth was as a miracle calling for devoutest gratitude; but to the great bulk of the English nation it was as the pledge of a continued attempt to reestablish the Church of Rome, and their hearts sunk within them at the news. Their only resource for a while was to support a very ill-founded rumour that the infant was supposititious-introduced in a warming-pan, it was said, into the queen's bedroom, that he might serve to exclude the Protestant princesses, Mary and Anne, from the throne. How uncertain are all calculations of the results of remarkable events What seemed likely to confirm the king on his throne, and assist in restoring the Catholic religion, proved very soon to have quite the contrary effect. It precipitated the Revolution, and before the close of the year, the little babe, which unconsciously was the subject of so much hope and dread, was, on a wet winter night, conveyed mysteriously across the Thames to Lambeth church, thence carried in a hackney coach to a boat, and embarked for France, leaving Protestantism in that safety which it has ever since enjoyed. Unwelcome at birth, this child came to a manhood only to be marked by the hatred and repugnance of a great nation. He lived for upwards of seventy-seven years as an exiled pretender to the throne of Britain. He participated in two attempts at raising civil war for the recovery of what he considered his rights, but on no occasion showed any vigorous qualities. A modern novelist of the highest reputation, and who is incapable of doing any gross injustice in his dealings with living men, has represented James as in London at the death of Queen Anne, and so lost in a base love affair as to prove incapable of seizing a throne then said to have been open to him. It is highly questionable how far, even in fiction, it is allowable thus to put historical characters in an unworthy light, the alleged facts being wholly baseless. Leaving this aside, it fully appears from the Stuart papers, as far as published, that the so-called Pretender was a man of amiable character and refined sentiments, who conceived that the interests of the British people were identical with his own. He had not the audacious and adventurous nature of his son Charles, but he was equally free from Charles's faults. If he had been placed on the throne, and there had been no religious difficulties in the case, he would probably have made a very respectable ruler. With reference to the son, Charles, it is rather remarkable that, after parting with him, when he was going to France in 1744, to prepare for his Scotch adventure, the father and the son do not appear ever to have met again, though they were both alive for upwards of twenty years after. The 'Old Pretender,' as James at length came to be called, died at the beginning of 1766. To quote the notes of a Scottish adherent lying before us, and it is appropriate to do so, as a pendent to Luttrell's statement of the birth: The 1st of January (about a quarter after nine o'clock at night) put a period to all the troubles and disappointments of good old Mr. JAMES MISFORTUNATE.' HEARNE, THE ANTIQUARYOld Tom Hearne, as he is fondly and familiarly termed by many even at the present day-though in reality he never came to be an old man-was an eminent antiquary, collector, and editor of ancient books and manuscripts. One of his biographers states that even from his earliest youth ' he had a natural and violent propensity for antiquarian pursuits.' His father being parish clerk of Little Waltham, in Berkshire, the infant Hearne, as soon as he knew his letters, began to decipher the ancient inscriptions on the tombstones in the parish churchyard. By the patronage of a Mr. Cherry, he received a liberal education, which enabled him to accept the humble, but congenial post of janitor to the Bodleian Library. His industry and acquirements soon raised him to the situation of assistant librarian, and high and valuable preferments were within his reach; but he suddenly relinquished his much-loved office, and all hopes of promotion, through conscientious feelings as a non-juror and a jacobite. Profoundly learned in books, but with little knowledge of the world and its ways, unpolished in manners and careless in dress, feeling imperatively bound to introduce his extreme religious and political sentiments at every opportunity, Hearne made many enemies, and became the butt and jest of the ignorant and thoughtless, though he enjoyed the approbation, favour, and confidence of some of his eminent contemporaries. Posterity has borne testimony to his unwearied industry and abilities; and it maybe said that he united much piety, learning, and talent with the greatest plainness and simplicity of manners. Anxiety to recover ancient manuscripts became in him a kind of religion, and he was accustomed to return thanks in his prayers when he made a discovery of this kind. Warton, the laureate, informs us of a waggish trick which was once played upon this simple-hearted man. There was an ale-house at Oxford in his time known by the sign of Whittington and his Cat. The kitchen of the house was paved with the bones of cheeps' trotters, curiously disposed in compartments. Thither Hearne was brought one evening, and shown this floor as a veritable tesselated Roman pavement just discovered. The Roman workmanship of the floor was not quite evident to Hearne at the first glance; but being reminded that the Standsfield Roman pavement, on which he had just published a dissertation, was dedicated to Bacchus, he was easily induced, in the antiquarian and classical spirit of the hour, to quaff a copious and unwonted libation of potent ale in honour of the pagan deity. More followed, and then Hearne, becoming convinced of the ancient character of the pavement, went down upon his knees to examine it more closely. The ale had by this time taken possession of his brain, and once down, he proved quite unable to rise again. The wags led the enthusiastic antiquary to his lodgings, and saw him safely put to bed. Hearne died in his fifty-seventh year, and, to the surprise of everybody, was found to possess upwards of a thousand pounds, which was divided among his poor brothers and sisters. BOARSTALL HOUSE This old mansion, memorable as the object of frequent contests in the civil wars, was finally surrendered to the Parliament on the 10th of June 1646. Willis called it 'a noble seat, and Hearne described it as 'an old house moated round, and every way fit for a strong garrison, with a tower at the north end much like a small castle.' This tower, which is still standing, formed the gate-house. It is a large, square, massive building, with a strong embattled turret at each corner. The entrance was across a drawbridge, and under a massive arch protected by a portcullis and thick ponderous door, strengthened with large studs and plates of iron. The. whole mansion, with its exterior fortifications, formed a post of strength and importance.  Its importance, however, consisted not so much in its strength as its situation; it stood at the western verge of Buckinghamshire, two miles from Brill, and about half way between Oxford and Aylesbury. Aylesbury was a powerful garrison belonging to the Parliament, and Oxford was the king's chief and strongest hold, and his usual place of residence during the civil wars. While Boarstall, therefore, remained a royal garrison, it was able to harass and plunder the enemy at Aylesbury, and to prevent their making sudden and unexpected incursions on Oxford and its neighbourhood. At an early period in the civil wars Boarstall House, then belonging to Lady Dynham, widow of Sir John Dynham, was taken possession of by the Royalists, and converted into a garrison; but in 1644, when it was decided to concentrate the king's forces, Boarstall, among other of the smaller garrisons, was abandoned. No sooner was this done than the impolicy of the measure became apparent. Parliamentary troops from Aylesbury took possession of it, and by harassing the garrison at Oxford, and by seizing provisions on the way there, soon convinced the Royalists that Boarstall was a military position of importance. It was therefore determined to attempt its recovery, and Colonel Gage undertook the enterprise. With a chosen party of infantry, a troop of horse, and three pieces of cannon, he reached Boarstall before daybreak. After a slight resistance, he gained possession of the church and out - buildings, from whence he battered the house with cannon, and soon forced the garrison to crave a parley. The result was that the house was at once surrendered, with its ammunition and provisions for man and horse; the garrison being allowed to depart only with their arms and horses.'' Lady Dynham, being secretly on the side of the parliament, withdrew in disguise. The house was again garrisoned for the king, under the command of Sir William Campion, who was directed to make it as strong and secure as possible. For this purpose he was ordered 'to pull down the church and other adjacent buildings,' and 'to cut down the trees for the making of pallisadoes, and other necessaries for use and defence.' Sir William Campion certainly did not pull down the church, though he probably demolished part of its tower. The house, as fortified by Campion, was thus described by one of the king's officers: There's a pallisado, or rather a stockado, without (outside) the graffe; a deep graffe and wide, full of water; a pallisado above the false bray; another six or seven feet above that, near the top of the curtain. The parliamentarian garrison at Aylesbury suffering seriously from that at Boarstall, several attempts were made to recover it, but without success. It was attacked by Sir William Walley in 1644; by General Skippon in May 1645; and by Fairfax himself soon afterwards. All were repulsed with considerable loss. The excitement produced in the minds of the people of the district by this warfare is described by Anthony it Wood, then a schoolboy at Thame, as intense. One day a body of parliamentary troopers would rush close past the castle, while the garrison was at dinner expecting no such visit. Another day, as the parliamentary excise committee was sitting with. a guard at Thame, Campion, the governor of Boarstall, would rush in with twenty cavaliers, and force them to fly, but not without a short stand at the bridge below Thame Mill, where half a score of the party was killed. On another occasion a large parliamentary party at Thame was attacked and dispersed by the cavaliers from Oxford and Boarstall, who took home twenty-seven officers and 200 soldiers as prisoners, together with between 200 and 300 horses. Some venison pasties prepared at the vicarage for the parliamentary soldiers fell as a prize to the schoolboys in the vicar's care. In such desultory warfare did the years 1644 and 1645 pass in Buckinghamshire, while the issue of the great quarrel between king and commons was pending. Happy for England that it has to look back upwards of two centuries for such experiences, while, sad to say, in other countries equally civilized, it has been seen that they may still befall! There was more than terror and excitement among the Bucks peasantry. Labourers were forcibly impressed into the garrisons; farmers' horses and carts were required for service without remuneration; their crops, cattle, and provender carried off;t gentlemen's houses were plundered of their plate, money, and provisions; hedges were torn up, trees cut down, and the country almost turned into a wilderness. A contemporary publication, referring to Boarstall in 1644, says: The garrison is amongst the pastures in the fat of that fertile country, which, though heretofore esteemed the garden of England, is now much wasted by being burthened with finding provision for two armies. And Taylor, the 'water-poet,' in his 'Lecture to the People,' addressed to the farmers of Bucks and Oxford-shire, says: Your crests are fallen down, And now your journies to the market town Are not to sell your pease, your oats, your wheat; But of nine horses stolen from you to intreat But one to be restored: and this you do To a buffed captain, or, perhaps unto His surly corporal. Nor was it only the property of the peaceable that suffered; their personal liberty, and very lives, were insecure. In November 1645, a considerable force from Boarstall and Oxford made a rapid predatory expedition through Buckinghamshire, carrying away with them several of the principal inhabitants, whom they detained till they were ransomed. In 1646, a party of dragoons from Aylesbury carried off Master Tyringham, parson of Tyringham, and his two nephews. They deprived them of their horses, their coats, and their money. 'They commanded Master Tyringham to pull off his cassock, who being not sudden in obeying the command, nor over hasty to untie his girdle to disroabe himself of the distinctive garment of his profession, one of the dragoons, to quicken him, cut him through the hat into the head with a sword, and with another blow cut him over his fingers. Master Tyringham, wondering at so barbarous usage without any provocation, came towards him that had thus wounded him, and desired him to hold his hands, pleading that he was a clergyman, a prisoner, and disarmed.' He was then hurried off to Aylesbury, but before reaching there he was deprived of his hat and cap, his jerkin and boots, and so severely wounded in one of his arms that it was found necessary the next day to amputate it. 'Master Tyringham (though almost three score years old) bore the loss of his arm with incredible resolution and courage.') Thus both parties were addicted to plunder, which is the inevitable consequence of civil war, and wanton cruelty is sure to follow in its train. In 1646, Sir William Fairfax again attacked Boarstall House, and though its valiant little garrison for some time resolutely resisted, it wisely decided, on account of the king's failing resources, to surrender on terms which were honourable to both parties. The deed of surrender was signed on the 6th of June 1646, but did not take effect till the 10th. On Wednesday, June 10th, says A. Wood, 'the garrison of Boarstall was surrendered for the use of the Parliament. The schoolboys were allowed by their master a free liberty that day, and many of them went thither (four miles distant) about eight or nine of the clock in the morning, to see the form of surrender, the strength of the garrison, and the soldiers of each party. They, and particularly A. Wood, had instructions given them before they went, that not one of them should either taste any liquor or eat any pro-vision in the garrison; and the reason was, for fear the royal party, who were to march out thence, should mix poison among the liquor or provision that they should leave there. But as A. Wood remembered, he could not get into the garrison, but stood, as hundreds did, without the works, where he saw the governor, Sir William Campion, a little man, who upon some occasion lay flat on the ground on his belly, to write a letter, or bill, or the form of a pass, or some such thing.' Boarstall House, being now entirely relinquished by the Royalists, was taken possession of by its owner, Lady Dynham. In 1651, Sir Thomas Fanshawe, who had been taken prisoner at the battle of Worcester, was brought here by his custodians on their way to London. He was kindly received by Lady Dynham, 'who would have given him,' writes Lady Fanshawe, 'all the money she had in the house; but he returned her thanks, and told her that he had so ill kept his own, that he would not tempt his governor with more; but that if she would give him a shirts two, and a few handkerchiefs, he would keep them as long as he could for her sake. She fetched him some shifts of her own, and some handkerchiefs, saying, that she was ashamed to give them to him, but having none of her son's shirts at home, she desired him to wear them.' The country having become more settled, Lady Dynham repaired her house and the church; but the tower of the latter, which had been demolished, was not restored. In 1668, Anthony Wood again visited Boarstall, and has recorded this curious account of it: A. W. went to Borstall, neare Brill, in Bucks, the habitation of the Lady Penelope Dinham, being quite altered since A. W, was there in 1646. For whereas then it was a garrison, with high bulwarks about it, deep trenches, and pallisadoes, now it had pleasant gardens about it, and several sets of trees well growne. Between nine and ten of the clock at night, being an hour or two after supper, there was seen by them, M. H. and A. W., and those of the family of Borstall, a Draco volans fall from the sky. It made the place so light for a time, that a man might see to read. It seemed to A. W. to be as long as All Saints' steeple in Oxon, being long and narrow; and when it came to the lower region, it vanished into sparkles, and, as some say, gave a report. Great raines and inundations followed. Towards the close of the seventeenth century, Sir John Aubrey, Bart., by his marriage with Mary Lewis, the representative of Sir John Dynham, became possessed of Boarstall; and it continued to be the property and residence of his descendants till it was pulled down by Sir John Aubrey, about the year 1783. This Sir John Aubrey married Mary, daughter of Sir James Colebrooke, Bart., by whom he had a son, named after himself, who was born the 6th of December 1771, and came to an early and melancholy death. When about five years old he was attacked with some slight ailment, for which his nurse had to give him a dose of medicine. After administering the medicine, she prepared for him some gruel, which he refused, saying 'it was nasty.' She put some sugar into it, and thus induced him to swallow it. Within a few hours he was a corpse! She had made the gruel of oatmeal with which arsenic had been mixed to poison rats. Thus died, on the 2nd of January 1777, the heir of Boarstall, and of all his father's possessions-the only child of his parents-the idol of his mother. The poor nurse, it is said, became distracted-the mother never recovered from the effects of the blow. She lingered out a year of grief, and then died at the early age of thirty-two, and, as her affecting memorial states, 'is deposited by the side of her most beloved son.' Sir John Aubrey, having thus lost his wife and child, pulled down the house in which they died, with the exception of the turreted gateway, and removed his residence to Dorton, carrying with him a painted window, and some other relics from the demolished house of Boarstall. He also pulled down the old church, which had been, much shattered in the civil war, and in 1818 built an entirely new one on the same spot. He married a second time, but dying in 1826 without issue, he was succeeded by his nephew, Sir Thomas Digby Aubrey, by whose death, in 1856, the male line of this very ancient family became extinct, and Boarstall is now the property of Mrs. Charles Spencer Ricketts, of Dorton House. The gate-house at Boarstall, which still exists in fair preservation, was built in 1312 by John de Hadlo, who then had license from Edward II 'to make a castle of his manor-house at Borstall.' Since the civil wars the drawbridge has been removed, and one of two arches, bearing the date of 1735, has been substituted, one side of the moat has been filled in, and some slight alterations made in the building itself, but it has still the appearance of a strong fortress, and is a good specimen of the castellated architecture of the period when it was built. Boarstall, according to a very ancient tradition, acquired its name from an interesting incident. It is situated within the limits of the ancient forest of Bernwood, which was very extensive and thickly wooded. This forest, in the neighbourhood of Brill, where Edward the Confessor had a palace, was infested with a ferocious wild boar, which had not only become a terror to the rustics, but a great annoyance to the royal hunting expeditions. At length one Nigel, a huntsman, dug a pit in a certain spot which he had observed the boar to frequent, and placing a sow in the pit, covered it with brushwood. The boar came after the sow, and falling into the pit, was easily killed by Nigel, who carried its head on his sword to the king, who was then residing at Brill. The king knighted him, and amply rewarded him. He gave him and his heirs for ever a hide of arable land, called Derehyde, a wood called Hulewood, with the custody of Bernwood Forest to hold from the king per unum coma quod est chartae predictae Forestae, and by the service of paying ten shillings yearly for the said land, and forty shillings yearly for all profits of the forest, excepting the indictment of herbage and hunting, which were reserved to the king. On the land thus acquired, perhaps on the very spot where he slew the boar, Nigel built a lodge or mansion, which, in commemoration of his achievement, he named Boar-stall. In testimony of this tradition, a field is still called '  Sow Close,' and the chartulary of Boarstall, which is a large folio in vellum, contains a rude delineation of the site of Borstall House and manor, and underneath the portraiture of a huntsman kneeling before the king, and presenting to him a boar's head on the point of a sword, and the king rewarding him in return with a coat-of-arms. The armorial bearings, which are, arg, a fesse gu, two crescents, and a horn verde, could not, of course, have been conferred by Edward the Confessor, but by some subsequent king. As, however, these arms were borne by Nigel's successors, they must here be regarded as an anachronistical ornament added by the draughtsman. The same figure of a boar's head presented to the king was, says Kennett, carved on the head of an old bedstead lately remaining in that strong and ancient house; and the said arms of Fitz-Nigel are now seen in the windows and in other parts. The tradition further states that the king (Edward the Confessor) conveyed his grant to Nigel by presenting to him a horn as the charter of his land, and badge of his office as forester. In proof of this, an antique horn, said to be the identical one given to Nigel, has descended with the manor, and is still in the possession of the present proprietor, Mrs. Spencer Ricketts, of Dorton House. This horn, which is two feet four inches long, is of a dark brown colour, resembling tortoiseshell. It is tipped at each end with silver gilt, and fitted with a leathern thong to hang round the neck; to this thong are suspended an old brass ring bearing the rude impression of a horn, a brass plate with a small horn of brass attached to it, and several smaller plates of brass impressed with fleurs-de-lis, which, says Kennett, are the arms of the Lizares, who intruded into the estate soon after the reign of William the Conqueror. There was also over one of the doors in the tower a painting or carving upon wood representing the king knighting Nigel. The late Sir Thomas Aubrey carried this to Oving House, his place of residence, and had it renovated, but where it is now is unknown. |