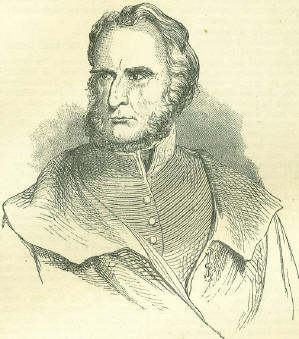

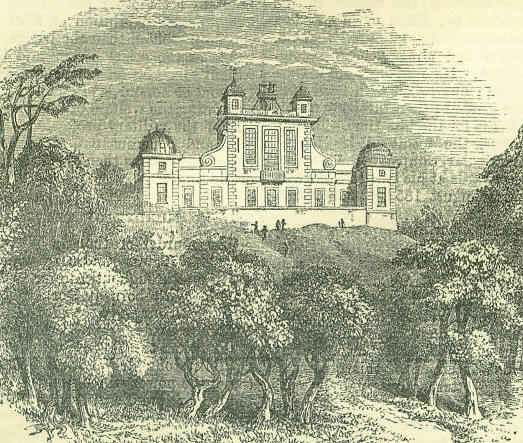

10th AugustBorn: Bernard Nieuwentyt, eminent Dutch mathematician, &c., 1654; Armand Gensonné, noted Girondist, 1758, Bordeaux; Sir Charles James Napier, conqueror of Scinde, 1782, Whitehall. Died: Magnentius, usurper of Roman empire, 353, Lyon; Henrietta Maria, queen of Charles I, 1669, Colombe, France; John de Witt and his brother Cornelius, eminent Dutch statesmen, murdered by the mob at the Hague, 1672; Cardinal Dubois, intriguing statesman, 1723, Versailles; Gabrielle Emilie de Breteuil, Marquise du Chastelet, translator of Newton's Principia, 1749, palace of Luneville; Dr. Benjamin Hoadly, eldest son of the bishop, and author of the Suspicious Husband, 1757, Chelsea; Ferdinand VI of Spain, 1759, Madrid; John Wilson Croker, Tory politician and reviewer, 1857. Feast Day: St. Lawrence, martyr, 258. St. Deusdedit, confessor. St. Blaan, bishop of Kinngaradha among the Picts, in Scotland, about 446 ST. LAWRENCEThis being a very early saint, his history is obscure. The Spaniards, however, with whom he is a great favourite, claim him as a native of the kingdom of Aragon, and even go so far as remark, that his heroism under unheard-of sufferings was partly owing to the dignity and fortitude inherent in him as a Spanish gentleman. Being taken to Rome, and appointed one of the deacons under Bishop Xystus, he accompanied that pious prelate to his martyrdom, anno 257, and only expressed regret that he was not consigned to the same glorious death. The bishop enjoined him, after he should be no more, to take possession of the church-treasures, and distribute them among the poor. He did so, and thus drew upon himself the wrath of the Roman prefect. He was called upon to account for the money and valuables which had been in his possession; The emperor needs them,' said he, 'and you Christians always profess that the things which are Caesar's should be rendered to Caesar.' Lawrence promised, on a particular day, to show him the treasures of the church; and when the day came, he exhibited the whole body of the poor of Rome, as being the true treasures of a Christian community. ' What mockery is this?' cried the officer. 'You desire, in your vanity and folly, to be put to death-you shall be so, but it will be by inches.' So Lawrence was laid upon a gridiron over a slow fire. He tranquilly bore his sufferings; he even jested with his tormentor, telling him he was now done enough on one side-it was time to turn him. While retaining his presence of mind, he breathed out his soul in prayers, which the Christians heard with admiration. They professed to have seen an extraordinary light emanating from his countenance, and alleged that the smell of his burning was grateful to the sense. It was thought that the martyrdom of Lawrence had a great effect in turning the Romans to Christianity. The extreme veneration paid to Lawrence in his native country, led to one remarkable result, which is patent to observation at the present day. The bigoted Philip II, having gained the battle of St. Quintin on the 10th of August 1557, vowed to build a magnificent temple and palace in honour of the holy Lawrence. The Escurial, which was constructed in fulfilment of this vow, arose in the course of twenty-four years, at a cost of eight millions, on a ground-plan which was designed, by its resemblance to a gridiron, to mark in a special manner the glory of that great martyrdom. The palace represents the handle. In its front stood a silver statue of St. Lawrence, with a gold gridiron in his hand; but this mass of the valuable metals was carried off by the soldiers of Napoleon. The only very precious article now preserved in the place, is a bar of the original gridiron, which Pope Gregory is said to have found in the martyr's tomb at Tivoli. The cathedral at Exeter boasted, before the Reformation, of possessing some of the coals which had been employed in broiling St. Lawrence. BERNARD NIEUWENTYT, THE REAL AUTHOR OF PALEY'S 'NATURAL THEOLOGY.'On the 10th of August 1654, the pastor of Westgraafdyke, an obscure village in the north of Holland, had a son born to him. This child, named Bernard Nieuwentyt, was educated for the ministry, but to the great disappointment of his reverend father, the youth resolutely declined to enter the church. Studying medicine, he acquired the degree of doctor; and then settled down contentedly in his native place in the humble capacity of village leech. Nieuwentyt, however, was very far from being an ordinary man. While the boorish villagers considered him an addlepated dunce, unable to acquire sufficient learning to fit him for the duties of a country minister, he was sedulously pursuing abstruse mathematical and philosophical studies; when he became a contributor to the Leipsic Transactions, the principal scientific periodical of the day, the learned men of Europe admired the abilities of the man who, by his neighbours, was considered to be little better than a fool. The talents of Nieuwentyt were at last recognised by his countrymen, and he was offered lucrative and honourable employment in the service of the state; but the unambitious student, finding in science its own reward, could never be persuaded to leave the seclusion of his native village. Though the name of Nieuwentyt is scarcely known in this country, yet the patient student of the obscure Dutch hamlet has left an important impress on English literature. Towards the close of the seventeenth century, he contributed a series of papers to the Leipsic Transactions, the object of which was to prove the existence and wisdom of God from the works of creation. These papers were collected, and published in Dutch, and subsequently translated into French and German. Mr. Chamberlayne, a Fellow of the Royal Society, translated the work into English, and it was published by the evergreen-house of Longman in 1718, under the title of The Religious Philosopher. The work achieved considerable popularity in its day, but, another line of argument becoming more fashionable, it fell into oblivion, and until a few years ago was utterly forgotten. In 1802, the well-known English churchman and author, William Paley, published his equally well-known Natural Theology. The well-merited popularity of this last work need not be noticed here; it has gone through many editions, and had many commentators, not one of whom seems ever to have suspected that it was not the genuine mental offspring of Archdeacon Paley. But, sad to say, for common honesty's sake, it must be proclaimed that Paley's Natural Theology is little more than a version or abstract, with a running commentary, of Nieuwentyt's Religious Philosopher! Many must remember the exquisite gratification experienced, when reading, for the first time, Paley's admirably interesting illustration of the watch. Alas! that watch was stolen, shamefully stolen, from Bernard Nieuwentyt, and unblushingly vended as his own, by William Paley! As a fair specimen of this great and gross plagiarism, a few passages on the watch-argument may be here adduced. The Dutchman finds the watch 'in the middle of a sandy down, a desert, or solitary place;' the Englishman on 'a heath;' and thus they describe it: Nieuwentyt: So many different wheels, nicely adapted by their teeth to each other. Paley: A series of wheels, the teeth of which catch in and apply to each other. Nieuwentyt: Those wheels are made of brass, in order to keep them from rust; the spring is steel, no other metal being so proper for that purpose. Paley: The wheels are made of brass, in order to keep them from rust; the spring of steel, no other metal being so elastic. Nieuwentyt: Over the hand there is placed a clear glass, in the place of which if there were any other than a transparent substance, he must be at the pains of opening it every time to look upon the hand. Paley: Over the face of the watch there is placed a glass, a material employed in no other part of the work, but in the room of which if there had been any other than a transparent substance, the hour could not have been seen without opening the case. The preceding quotations are quite sufficient to prove the identity of the two works. Paley, in putting forth the Natural Theology as his own, may have been guided by his favourite doctrine of expediency; but if he did not succumb to the temptation of wilful fraud, he must have had very confused ideas on the all-important subject of meum and tuum. And no one can have any hesitation in naming Bernard Nieuwentyt the author of Paley's Natural Theology. In conclusion, it may be added that, though everybody knows the meaning of the words plagiarist and plagiarism, yet few persons are acquainted with their derivation. Among the more depraved classes in ancient Rome, there existed a nefarious custom of stealing children and selling them as slaves. According to law, the child-stealers, when detected, were liable to the penalty of being severely flogged; and as the Latin word playa signifies a stripe or lash, the ancient kidnappers were, in Cicero's time, termed plagiari-that is to say, deserving of, or liable to, stripes; and thus both the crime and criminals received their names from the punishment inflicted. SIR CHARLES JAMES NAPIER When one recalls the character and expressions of this person and his brother William, author of The History of the Peninsular War, he cannot but feel a curiosity to learn whence was derived ability so vivid and blood so hot. They were two of the numerous sons of the Hon. George Napier, 'comptroller of accounts in Ireland,' a descendant of the celebrated inventor of the logarithms, but more immediately of Sir William Scott of Thirlstain, a scholar and poet of the reign of Queen Anne. Their mother was the Lady Sarah Lennox, a great-grand-daughter of Charles II, and the object of a boyish flame of George III. The attachment of Charles Napier to his mother was deep and lasting, as his many letters to her attest; she lived to see him advance to middle life, and one envies the pride which a woman must have had in such a son. In childhood, the future conqueror of Scinde was sickly, and of a demure and thoughtful turn, but he early displayed an ardent enthusiasm for a military life. When only ten years of age, he rejoiced to find he was short-sighted, because a portrait of Frederick the Great, which hung up in his father's room, had strange eyes, and he had heard Plutarch's statement mentioned, that Philip, Sertorius, and Hannibal had each only one eye, and that Alexander's eyes were of different colours. The young aspirant for military fame even wished to lose one of his own eyes, as the token of a great general; a species of philosophy which recalls to mind the promising youth, depicted by Swift, who had all the defects characterising the great heroes of antiquity. Though naturally of a very sensitive temperament, he overcame all his tendencies to timidity by his wonderful force of will, and became almost case-hardened both to fear and pain. Throughout life, from boyhood to old age, he was constantly meeting with accidents, which, however, had no effect in diminishing his passion for perilous adventures. On one occasion, when a mere boy, he struck his leg in leaping against a bank of stones, so as to inflict a frightful wound, which, however, he bore with such stoical calmness as to excite the admiration of many rough and stern natures. Another time, at the age of seventeen, he broke his right leg leaping over a ditch when shooting, and by making a further scramble after being thus disabled, to get hold of his gum, produced such a laceration of the flesh, and extravasation of blood, that it was feared by the surgeons that amputation would be necessary. This was terrible news to the youth, as he rather piqued himself on a pair of good legs, and he resolved, according to his own account, to commit suicide rather than survive such a mutilation. The servant was sent out by him for a bottle of laudanum, which he hid under his pillow; but in the meantime a change for the better took place in the condition of his limb, and the future hero was saved to his country. But the pains of this misfortune were not yet over; the leg was set crooked, and it became necessary to bend it straight by bandages, an operation which fortunately succeeded, and left the limb, to use his own words, 'as straight a one, I flatter myself, as ever bore up the body of a gentleman, or kicked a blackguard.' His narration of this adventure, written many years afterwards, affords a striking specimen of the wonderful vigour of his character, and we have only to regret that our space does not allow us to transcribe it at full length. A curious incident connected with his boyish days, which the ancients would have regarded as a presage of his future greatness, ought not to be omitted. Having been out angling one day, he had caught a fish, and was examining his prize, when a huge eagle flopped down upon him, and carried off the prey out of his hands. Far, however, from being frightened, he continued his sport, and on catching another fish, held it up to the royal bird, who was seated on an adjoining tree, and invited him to try his luck again. In the days of which we write, mere boys were often gazetted to commissions in the army; an abuse in connection with which many of our readers will remember the story of the nursery-maid announcing to the inquiring mamma, who had been disturbed one morning by an uproar overhead, 'that it was only the major greeting for his porridge.' In 1794, when only twelve years old, young Napier obtained a commission in the 33d, or Duke of Wellington's Regiment, but was afterwards successively transferred to the 89th and 4th Regiments. After this he attended a school at Celbridge, a few miles from Dublin, and made himself conspicuous there by raising, among the boys, a corps of volunteers. In 1799, he first entered really on the duties of his profession by becoming aid-de-camp to Sir James Duff, a staff situation, which he afterwards resigned to his brother George, to enter as a lieutenant the 95th or Rifle Corps. After the peace of Amiens he made further changes, and in 1806 entered the 50th Regiment as major, a capacity in which he was present at the battle of Coruna, of his share in which he subsequently penned a most graphic and interesting account. He was here severely wounded in different parts of the body; and at last, after enduring an amount of pain and exposure which would have terminated the existence of any other man, was taken prisoner by the French, and detained for three months in captivity. His liberation was owing to the generosity of Marshal Ney, who, on hearing that he had an old mother, widowed and blind, magnanimously ordered that he should be released, and thereby exposed himself to the serious displeasure of Bonaparte. Rejoining, after a while, his regiment in the Peninsula, Charles Napier received a dreadful wound at the battle of Busaco, by which his upper jaw-bone was shattered to pieces, causing unspeakable agony, both at the time of extraction of the bullet, and for many months afterwards. The gaiety, however, and elasticity of spirit which he manifested on no occasion more conspicuously than during pain and suffering, are most whimsically given utterance to in a letter to a friend at home, in which he says that he offered a piece of his jaw-bone, which came away with the bullet, to a monk for a relic; telling him, at the same time, that it was a piece of St. Paul's wisdom-tooth, which he had received from the Virgin Mary in a dream! The holy man, he adds, would have carried it off to his convent, but on being demanded a price for it, said he never gave money for relics, upon which Napier returned it to his pocket. In another letter he compares himself, with six wounds in two years, to General Kellarman, who had as many wounds as he was years old-thirty-two. On recovering to a certain extent from his Busaco wound, he again took the field, was present at the battle of Fuentes de Onoro and the second siege of Badajoz; and in 1811 was promoted to a lieutenant-colonelcy in a colonial corps, and sent out to Bermuda. Towards the end of 1814 he returned to England, was placed on half-pay, and with the view of studying the theory of his profession, entered, with his brother William, the Military College at Farnham, where he remained for two years. A period of comparative inaction followed, but in 1822 he received the appointment of military governor of Cephalonia-a situation in which he was more successful in gaining the affections of the inhabitants than pleasing the authorities at home, and his vocation consequently came to an end in 1830. The most important epoch in Sir Charles Napier's life was yet to come, and in 1842, at the age of sixty, he was appointed as major-general to the command of the Indian army within the Bombay presidency. Here Lord Ellenborough's policy led Napier to Scinde, for the purpose of quelling the Ameers, who had made various hostile demonstrations against the British government after the termination of the Afghan war. His campaign against these chieftains resulted, as is well known, after the victories of Meanee and Hyderabad, in the complete subjugation of the province of Scinde, and its annexation to our eastern dominions. Appointed its governor by Lord Ellenborough, his administration was not such as pleased the directors of the East India Company, and he accordingly returned home in disgust, but was sent out again by the acclamatory voice of the nation, in the spring of 1849, to reduce the Sikhs to submission. On arriving once more in India, he found that the object of his mission had already been accomplished by Lord Gough. He remained for a time as commander-in-chief; quarrelled with Lord Dalhousie, the governor-general; then throwing up his post, he returned home for the last time. Broken down with infirmities, the result of his former wounds in the Peninsular campaign, he expired about two years afterwards at his seat of Oaklands, near Portsmouth, in August 1853, at the age of seventy-one. The letters of Sir Charles Napier, as published by his brother and biographer, Sir William Napier, the distinguished military historian, exhibit very decidedly the stamp of an original and vigorous mind, blended with a certain degree of eccentricity, which evinces itself no less in him than in his eminent cousin and namesake, Admiral Sir Charles Napier, of naval and parliamentary celebrity. A curious specimen of this quality is given in the following letter, addressed by him to a private soldier: Private James N____ y: I have your letter. You tell me you give satisfaction to your officers, which is just what you ought to do; and I am very glad to hear it, because of my regard for every one reared at Castletown, for I was reared there myself. However, as I and all belonging to me have left that part of the country for more than twenty years, I neither know who Mr. Tom Kelly is, nor who your father is; but I would go far any day in the year to serve a Celbridge man; or any man from the barony of Salt, in which Celbridge stands: that is to say, if such a man behaves himself like a good soldier, and not a drunken vagabond, like James J____e, whom you knew very well, if you are a Castletown man. Now, Mr. James N--y, as I am sure you are, and must be a remark-ably sober man, as I am myself, or I should not have got on so well in the world as I have done: I say, as you are a remarkably sober man, I desire you to take this letter to your captain, and ask him to show it to your lieutenant-colonel, and ask the lieutenant-colonel, with my best compliments, to have you in his memory; and if you are a remarkably sober man, mind that, James N y, a remarkably sober man, like I am, and in all ways fit to be a lance-corporal, I will be obliged to him for promoting you now and hereafter. But if you are like James J--e, then I sincerely hope he will give you a double allowance of punishment, as you will deserve for taking up my time, which I am always ready to spare for a good soldier but not for a bad one. Now, if you behave well, this letter will give you a fair start in life; and if you do behave well, I hope soon to hear of your being a corporal. Mind what you are about, and believe me your well-wisher, Charles Napier, major-general and governor of Scinde, because I have always been a remarkably sober man.' The sobriety to which the writer of the above refers in such whimsical terms was eminently characteristic of Sir Charles Napier through life. He abstained habitually from the use of wine or other fermented liquor, and was even a sparing consumer of animal food, restricting himself entirely, at times, to a vegetable diet. Though of an ardent enthusiastic temperament, impetuous in all his actions, and a most devoted champion of the fair sex, his moral deportment throughout was of the most unblemished description, even in the fiery and unbridled season of youth. His attachment to his mother has already been alluded to, and no finer exhibition of filial love and respect can be presented than the letters written home to her from the midst of war and bloodshed, by her gallant son. As an officer and gentleman, he was the soul of honour, and devoted above all things to promoting the welfare of the army, and the elevation of the military profession. And the uprightness and generous nature of the man were not more conspicuous than the energy, zeal, and courage of the soldier. MURDER OF THE DE WITTSThe murder of the De Witts, on the 10th of August 1672, was an atrocity which attracted much attention throughout Europe. John and Cornelius de Witt, born at Dort, in Holland, were the sons of a burgomaster of that town. John, in 1652, was made Grand Pensioner of Holland. At a time when the Seven United Provinces formed a republic, John de Witt was favourable to a lessening of the power which was possessed by the stadtholder or president, and which was gradually becoming too much assimilated to sovereign power to be palatable to true republicans. During the minority of William, Prince of Orange ( afterwards king of England), the office of stadtholder was held in suspension, and the United Provinces were ruled by the states-general, in which John de Witt was all-powerful. It was virtually he who negotiated a peace with Cromwell in 1652; who afterwards carried on war with England; who sent the fleet which shamed the English by burning some of the royal ships in the Medway; who concluded the peace of Breda in 1667; and who formed a triple alliance with England and Sweden, to guarantee the possessions of Spain against the ambition of Louis XIV. De Witt's plans concerning foreign policy were cut short by a manoeuvre on the part of France to rekindle animosity between England and Holland. A French army suddenly entered the United Provinces in 1672, took Utrecht, and advanced to within a few miles of Amsterdam. It was just at this crisis that home-politics turned out unfavourably for De Witt. He had given offence previously by causing a treaty to be ratified directly by the states-general, instead of first refering it, according to the provision of the Federation, to the acceptance of the seven provinces separately-a question, translated into the language of another country and a later date, of 'States' rights' as against 'Federal rights.' He had also raised up a party against him by procuring the passing of an edict, abolishing for ever the office of stadtholder. When the French suddenly appeared at the gates of the republican capital, those who had before been discontented with De Witt accused him of neglecting the military defences of the country. William, the young Prince of Orange, was suddenly invested with the command of the land and sea forces. About this time, Cornelius de Witt, who had filled several important civil and military offices, was accused of plotting against the life of William of Orange; he was thrown into prison, tortured, and sentenced to banishment. The charge appears to have been wholly unfounded, and to have originated in party malice. John de Witt, whose life had already been attempted by assassins, resigned his office, and went to the Hague in his carriage to receive his brother as he came out of prison. A popular tumult ensued, during which a furious mob forced their way into the prison, and murdered both the brothers with circumstances of peculiar ferocity. John de Witt, by far the more important man of the two, appears to have possessed all the characteristics of a patriotic, pure, and noble nature. The times in which he lived were too precarious and exciting to allow him to avoid making enemies, or to enable him, under all difficulties, to see what was best for his country; but posterity has done him justice, as one of the great men of the seventeenth century. FOUNDING OF GREENWICH OBSERVATORYOn the 10th of August 1675, a commencement was made of that structure which has done more for astronomy, perhaps, than any other building in the world-Greenwich Observatory. It was one of the few good deeds that marked the public career of Charles II. In about a year the building was completed; and then the king made Flamsteed his astronomer-royal, or 'astronomical observator,' with a salary of £100 a year. The duties of Flamsteed were thus defined-'forthwith to apply him-self, with the most exact care and diligence, to the rectifying the table of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so much-desired longitude of places for the perfecting the art of navigation.' It will thus be seen that the object in view was a directly practical I one, and did not contemplate any study of this noble science for its own sake.  How the sphere of operations extended during the periods of service of the successive astronomers-royal-Flamsteed, Halley, Bradley, Bliss, Maskelyne, Pond, and Airy-it is the province of the historians of astronomy to tell. Flamsteed laboriously collected a catalogue of nearly three thousand stars; Halley directed his attention chiefly to observations of the moon; Bradley carried the methods of minute measurements of the heavenly bodies to a degree of perfection never before equalled; Bliss confined his attention chiefly to tabulating the relative positions of sun, moon, and planets; Maskelyne was the first to measure such minute portions of time as tenths of a second, in the passage of stars across the meridian; Pond was enabled to apply the wonderful powers of Troughton's instruments to the starry heavens; while Airy's name is associated with the very highest class of observations and registration in every department of astronomy. Considered as a building, Greenwich Observatory has undergone frequent changes, to adapt it to the reception of instruments either new in form, large in size, or specially delicate in action. Electricity has introduced a whole series of instruments entirely unknown to the early astronomers; akin in principle to the electric telegraph, and enabling the observers to record their observations in a truly wonderful way. Again, photography is enabling astronomers to take maps of the moon and other heavenly bodies with a degree of accuracy which no pencil could equal. Meteorology, a comparatively new science, has been placed under the care of the astronomer-royal in recent years-so far as concerns the use of an exquisite series of instruments for recording (and most of them self-recording) the various phenomena of the weather. The large ball which surmounts one part of Greenwich Observatory falls at precisely one o'clock (mean solar time) every day, and thus serves as a signal or monitor whereby the captains of ships about to depart from the Thames can regulate the chronometers, on which the calculation of their longitudes, during their distant voyages, so much depends. The fall of this ball, too, by a series of truly wonderful electrical arrangements, causes the instantaneous fall of similar balls in London, at Deal, and elsewhere, so that Greenwich time can be known with extreme accuracy over a large portion of the kingdom. During every clear night, experienced observers are watching the stars, planets, moon, &c. with telescopes of wonderful power and accuracy; and during the day, a staff of computers are calculating and tabulating the results thus obtained, to be published annually at the expense of the nation. The internal organisation of the observatory is of the most perfect kind; but it can be seen by very few persons, except those officially employed, owing to the necessity of keeping the observers and computers as free as possible from interruption. John Flamsteed, who presided over the founding of the Greenwich Observatory, and from whom it was popularly called Flamsteed House, was of humble origin, and weakly and unhealthy in childhood (born 19th August 1646; died December 31th, 1719). His father, a maltster at Derby, set him to carry out malt with the brewing-pan, which he found a very tiresome way of effecting the object; so he set to, and framed a wheel-barrow to carry the malt. The father then gave him a larger quantity to carry, and young Flamsteed felt the disappointment so great, that he never after could bear the thoughts of a wheel-barrow. Many years after, when he reigned as the astronomer-royal in the Greenwich Observatory, he chanced once more to come into unpleasant relations with a wheel-barrow. Having one day spent some time in the Ship Tavern with two gentlemen-artists, of his acquaintance, he was taking a rather ceremonious leave of them at the door, when, stepping backwards, he plumped into a wheel-barrow. The vehicle immediately moved off down-hill with the philosopherin it; nor did it stop till it had reached the bottom, much to the amusement of the by-standers, but not less to the discomposure of the astronomer-royal. THE TENTH OF AUGUSTThe 10th of August 1792 is memorable in modern European history, as the day which saw the abolition of the ancient monarchy of France in the person of the unfortunate Louis XVI. The measures entered upon by prince and people for constitutionalising this monarchy had been confounded by a mutual distrust which was almost inevitable. When the leading reformers, and the populace which gave them their strength, found at length that Austria and Prussia were to break in upon them with a reaction, they grew desperate; and the position of the king became seriously dangerous. In our day, such attempts at intervention are discouraged, for we know how apt they are to produce fatal effects. In 1792, there was no such wisdom in the world. It was at the end of July that the celebrated manifesto announcing the plans of Austria and Prussia reached Paris. The people broke out in fury at the idea of such insulting menaces. Louis himself was in dismay at this manifesto, for it went far beyond anything that he had himself wished or expected. But his people would not believe him. An indescribable madness seized the nation; and 'Death to the aristocrats!' was everywhere the cry. 'Whatever,' says Carlyle, 'is cruel in the panic-fury of twenty-five million men, whatsoever is great in the simultaneous death-defiance of twenty-five million men, stand here in abrupt contrast, near by one another.' During the night between the 9th and 10th of August, the tocsin sounded all over Paris, and the rabble were invited to scenes of violence by the more unscrupulous leaders-against the wish of many who would even have gone so far as to dethrone the king. Danton gave out the fearful words: 'We must strike, or be stricken!' Nothing more was needed. The danger to the royal family being now imminent, numbers of loyal men hastened to the Tuileries with an offer of their swords and lives. There were also at the palace several hundred Swiss Guards, national guards, and gens d'armes. The commandant, Mandat, placed detachments to guard the approaches to the palace as best he could. When, at six o'clock in the morning, the insurgent mob, armed with cannon as well as other weapons, came near the Tuileries, the unfortunate Louis found that none of his troops were trustworthy save the Swiss Guards: the rest betrayed their trust at the critical moment. A day of horror then commenced. Mandat, the commander of the national guard, going to consult the authorities at the Hotel de Ville, was knocked down with clubs, and butchered by the mob. They then put to death four persons in the Champs Elyseès, whose only fault was that they wore rapiers, and looked like royalists; the heads of these hapless persons, stuck on pikes, were paraded about. The lives of the unhappy royal family were placed in such peril, that they were compelled to take refuge within the walls of the Legislative Assembly, hostile as that assembly was to the king. Louis, his queen, and their children walked the short distance from the palace-doors to the assembly-doors; but even in this short distance the king had to bear the jeers and hisses of the populace; while the queen, who was an object of intense national hatred, was met with a torrent of loathsome epithets. All through the remainder of that distressing day, the royal family remained ignobly cooped up in a reporter's box at the Legislative Assembly, where, without being seen, they had to listen to speeches and resolutions levelled against kingly power in all its forms; for the assembly, though at this moment protecting the king, was on the eve of dethroning him. Meanwhile blood was flowing at the Tuileries. None of the troops remained faithful to the royal cause except the Swiss Guards, who defended the palace with undaunted resolution, and laid more than a thousand of the insurgents in the dust. A young man, destined to world-wide notoriety, Napoleon Bonaparte, who was in the crowd, declared that the Swiss Guards would have gained the day had they been well commanded. But a fatal indecision ruined all. The poor king was persuaded to send an order to them, commanding them to desist from firing upon 'his faithful people,' as the insurgents were called. The end soon arrived. The rabble forced an entrance into the palace, and even dragged a cannon upstairs to the state-rooms. The Swiss Guards were butchered almost to a man; many of the courtiers and servants were killed while attempting to escape by the windows; some were killed and mutilated after they had leaped from the windows to the ground; while others were slaughtered in the apartments. The Parisians had not yet tasted so much blood as to be rabid against the lives of tender women. Madame Campan, the Princess de Tarente, and a few other ladies were saved from slaughter by a band of men whose hands were still gory, and who said: 'Respite to the women! do not dishonour the nation!' They were escorted safely to a private house; but they had to walk over several dead bodies, to see murder going on around them, to find their dresses trailing in pools of blood, and to see a band of hideous women carrying the head of Mandat on a pike! This terrible day inaugurated the French Revolution. The king and queen were never again free. THE MODERN SAMSONThomas Topham, born in London about 1710, and brought up to the trade of a carpenter, though by no means remarkable in size or outward appearance, was endowed by nature with extraordinary muscular powers, and for several years exhibited wonderful feats of strength in London and the provinces. The most authentic account of his performances was written by the celebrated William Hutton, who witnessed them at Derby. We learned, says Mr. Hutton, that Thomas Topham, a man who kept a public-house at Islington, performed surprising feats of strength, such as breaking a broomstick of the largest size by striking it against his bare arm, lifting three hogs-heads of water, heaving his horse over a turnpike-gate, carrying the beam of a house, as a soldier does his firelock, and others of a similar description. However belief might at first be staggered, all doubt was removed when this second Samson came to Derby, as a performer in public. The regular performances of this wonderful person, in whom was united the strength of twelve ordinary men, were such as the following: Rolling up a pewter dish, seven pounds in weight, as a man would roll up a sheet of paper; holding a pewter-quart at arm's length, and squeezing the sides together like an egg-shell; lifting two hundred weights on his little-finger, and moving them gently over his head. The bodies he touched seemed to have lost their quality of gravitation. He broke a rope that could sustain twenty hundredweight. He lifted an oaken-table, six feet in length, with his teeth, though half a hundred-weight was hung to its opposite extremity. Weakness and feeling seemed to have left him altogether. He smashed a cocoa-nut by striking it against his own car; and he struck a round bar of iron, one inch in diameter, against his naked arm, and at one blow bent it into a semicircle. Though of a pacific temper, says Mr. Hutton, and with the appearance of a gentleman, yet he was liable to the insults of the rude. The ostler at the Virgin's Inn, where he resided, having given him some cause of displeasure, he took one of the kitchen-spits from the mantel-piece, and bent it round the ostler's neck like a handkerchief; where it excited the laughter of the company, till he condescended to untie it. This remarkable man's fortitude of mind was by no means equal to his strength of body. Like his ancient prototype, he was not exempt from the wiles of a Delilah, which brought him to a miserable and untimely end (August 10th, 1749). SUPERSTITIONS AND SAYINGS REGARDING THE MOON AND THE WEATHERIn connection with Greenwich Observatory, it may not be improper to advert to one of the false notions which that institution has helped to dispel-namely, the supposed effect of the moon in determining the weather. It is a very prevalent belief, that the general condition of the atmosphere throughout the world during any lunation depends on whether the moon changed before or after midnight. Almanacs some-times contain a scientific-looking table constructed on this principle, the absurdity of which appears, if on no other grounds, from the consideration that what is calculated for the meridian of Greenwich may not be correct elsewhere, for the moon may even change before twelve o'clock at Westminster, and after it at St. Paul's. If I recollect rightly, this was actually the case with regard to the Paschal full-moon a few years ago, the consequence of which (unless Greenwich-time had been silently assumed to be correct) would have been that Easter-day must have fallen at different times in London and Westminster. There are other notions about the moon which are of a still more superstitious nature. In this part of the world (Suffolk), it is considered unlucky to kill a pig in the wane of the moon; if it is done, the pork will waste in boiling. I have known the shrinking of bacon in the pot attributed to the fact of the pig having been killed in the moon's decrease; an I have also known the death of poor .piggy delayed, or hastened, so as to happen during its increase. The worship of the moon (a part of, perhaps, the oldest of false religions) has not entirely died out in this nineteenth century of the Christian era. Many persons will courtesy to the new moon on its first appearance, and turn the money in their pockets 'for luck.' Last winter, I had a set of rough country lads in a night-school; they happened to catch sight of the new moon through the window, and all (I think) that had any money in their pockets turned it 'for luck.' As may be supposed, it was done in a joking sort of way, but still it was done. The boys could not agree what was the right form of words to use on the occasion, but it seemed to be understood that there was a proper formula for it. Another superstition was acknowledged by them at the same time-namely, that it was unlucky to see the new moon for the first time through glass. This must, of course, be comparatively modern. I do not know what is the origin of it, nor can I tell that of the saying: A Saturday moon, If it comes once in seven years, Comes once too soon. The application of this is, that if the new moon happens on a Saturday, the weather will be bad for the ensuing month. The average of the last seven years gives exactly two Saturday moons per annum, which is rather above the general average due from the facts of there being seven days to the week, and twenty-nine and a half to the lunation. This year, however (1863), there is but one Saturday moon, which brings the average nearer to the truth. I mention this to illustrate the utter want of observation which can reckon a septennial recurrence of a Saturday moon as something abnormal. Yet many sayings about the weather are, no doubt, founded upon observation; such appears to be the following: Rain before seven, Fine before eleven. At anyrate, I have hardly ever known it fail in this district; but it must be borne in mind it is only about ten miles from Thetford, where the annual rainfall is no more than nineteen inches, the lowest registered at any place in the kingdom. Another saying is, that 'There never is a Saturday without sunshine.' This is almost always true, but, as might be supposed from the low annual rainfall, the same might be said of any day in the week with an equal amount of truth. The character of St. Swithin's Day is much regarded here as a prognostication of fine or wet weather; but I am happy to think that the saint failed to keep his promise this year, and though he rained on his own day, did not feel himself obliged to go on with it for the regulation forty days. Another weather-guide connected with the moon is, that to see 'the old moon in the arms of the new one' is reckoned a sign of fine weather; and so is the turning up of the horns of the new moon. In this position it is supposed to retain the water, which is imagined to be in it, and which would run out if the horns were turned down. The streaks of light often seen when the sun shines through broken clouds are believed to be pipes reaching into the sea, and the water is supposed to be drawn up through them into the clouds, ready to be discharged in the shape of rain. With this may be compared Virgil's notion, 'Et bibit ingens Arcus' (Georg. I. 380); but it is more interesting, perhaps, as an instance of the truth sometimes contained in popular superstitions; for, though the streaks of sun-light are no actual pipes, yet they are visible signs of the sun's action, which, by evaporating the. waters, provides a store of vapour to be converted into rain. Suffolk. C. W. J. |