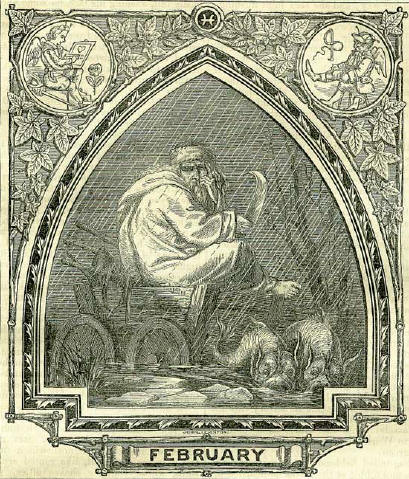

February Then came old February, sitting In an old wagon, for he could not ride, Drawn of two fishes for the season fitting, Which through the flood before did softly slide And swim away; yet had he by his side His plough and harness fit to till the ground, And tools to prime the trees, before the pride Of hasting prime did make them bourgeon wide. DESCRIPTIVEFebruary comes in like a sturdy country maiden, with a tinge of the red, hard winter apple on her healthy cheek, and as she strives against the wind, wraps her russet-coloured cloak well about her, while with bent head, she keeps throwing back the long hair that blows about her face, and though at times half blinded by the sleet and snow, still continues her course courageously. Sometimes she seems to shrink, and while we watch her progress, half afraid that she will be blown back again into the dreary waste of Winter, we see that her course is still forward, that she never takes a backward step, but keeps journeying along slowly, and drawing nearer, at every stride, to the Land of Flowers. Between the uplifted curtaining of clouds, that lets in a broad burst of golden sunlight, the skylark hovers like a dark speck, and cheers her with his brief sweet song, while the mellow-voiced blackbird and the speckle-breasted thrush make music among the opening blossoms of the blackthorn, to gladden her way; and she sees faint flushings of early buds here and there, which tell her the long miles of hedgerows will soon be green. Now there is a stir of life in the long silent fields, a jingling of horse-gear, and the low wave-like murmur of the plough-share, as it cuts through the yielding earth, from the furrows of which there comes a refreshing smell, while those dusky foragers, the rooks, follow close upon the ploughman's heels. Towards the end of the month the tall elm-trees resound with their loud 'cawing' in the early morning, and the nests they are busy building shew darker every day through the leafless branches, until Spring comes and hides them beneath a covering of foliage. Even in smoky cities, in the dawn of the lengthening days, the noisy sparrows come out from under the blackened eaves, and, as they shake the soot from off their wings, give utterance to the delight they feel in notes that sound like the grating jar of a knife-grinder's dry wheel. Now and then the pretty goldfinch breaks out with its short song, then goes peeping about as if wondering why the young green groundsel is so long before putting forth its dull golden flowers. The early warbling of the yellow-hammer is half drowned by the clamorous jackdaws that now congregate about the grey church steeples. Then Winter, who seems to have been asleep, shews his cloudy form once more above the bare hilltops, from whence he scatters his snow-flakes; while the timid birds cease their song, and again shelter in the still naked hedgerows, seeming to marvel to themselves why he has returned again, after the little daisy buds had begun to thrust their round green heads above the earth, announcing his departure. But his long delay prevents not the willow from shooting out its silvery catkins, nor the graceful hazel from unfurling its pendulous tassels; while the elder, as if bidding defiance to Winter, covers its stems with broad buds of green. The long-tailed field-mouse begins to blink at intervals, and nibble at the stores he hoarded up in autumn; then peeping out and seeing the snow lie among the young violet leaves, at the foot of the oak amid whose roots he has made his nest, he coils himself up again after his repast, and enjoys a little more sleep. Amid the wide-spreading branches over his head, the raven has begun to build; and as he returns with the lock of wool he has rent from the back of some sickly sheep to line his nest, he disturbs the little slumberer below by his harsh, loud croaking. That ominous sound sends the affrighted lambs off with a scamper to their full-uddered dams, while the raven looks down upon them with hungry eye, as if hoping that some one will soon cease its pitiful bleating, and fall a sacrifice to his horny beak. But the silver-frilled daisies will soon star the ground where the lambs now race against each other, and the great band of summer-birds will come from over the sunny sea, and their sweet piping be heard in place of the ominous croaking of the raven. The mild days of February cause the beautifully-formed squirrel to wake out of his short winter sleep, and feed on his hoarded nuts; and he may now be seen balanced by his hind legs and bushy tail, washing his face, on some bare bough near his dray or nest, though at the first sound of the voices of the boys who come to hunt him, he is off, and springs from tree to tree with the agility of a bird. It is only when the trees are naked that the squirrel can be hunted, for it is difficult to catch a glimpse of him when 'the leaves are green and long;' and it is an old country saying, when anything unlikely to be found is lost, that ' you might as well hunt a squirrel when the leaves are out.' Country boys may still be seen hiding at the corner of some out-building, or behind some low wall or fence, with a string in their hands attached to the stick that supports the sieve, under which they have scattered a few crumbs, or a little corn, to tempt the birds, which become more shy every day, as insect-food is now more plentiful. With what eager eyes the boys watch, and what a joyous shout they raise, as the sieve falls over some feathered prisoner! But there is still ten chances to one in favour of the bird escaping when they place their hands under the half-lifted sieve in the hope of laying hold of it. The long dark nights are still cold to the poor shepherds, who are compelled to be out on the windy hills and clowns, attending to the ewes and lambs, for thousands would be lost at this season were it not for their watchful care. In some of the large farmhouses, the lambs that are ailing, or have lost their dams, may be seen lying before the fire in severe weather; and a strange expression-as it seemed to us-beamed from their gentle eyes, as they looked around, bleating for something they had lost; and as they licked our hands, we felt that we should make but poor butchers. And there they lie sheltered, while out-of-doors the wind still roars, and the bare trees toss about their naked arms like maniacs, shaking down the last few withered leaves in which some of the insects have folded up their eggs. Strange power! which we feel, but see not; which drives the fallen leaves before it, like routed armies; and ships, whose thunder shakes cities, it tosses about the deep like floating sea-weeds, and is guided by Him 'who gathereth the winds in His fists.' 'February fill-dyke' was the name given to this wet slushy month by our forefathers, for when the snow melted, the rivers overflowed, the dykes brimmed over, and long leagues of land were under water, which have been drained within the last century; though miles of marshes are still flooded almost every winter, the deep silt left, enriching future harvests. It has a strange appearance to look over a wide stretch of country, where only the tops of the hedgerows or a tree or two are here and there visible. All the old familiar roads that led along pleasant streams to far-away thorpe or grange in summer, are buried beneath the far-spreading waters. And in those hedges water-rats, weasels, field-mice, and many another seldom-seen animal, find harbourage until the waters subside: we have there found the little harvest-mouse, that when full grown is no bigger than a large bee, shivering in the bleak hedgerow. And in those reedy fens and lonesome marshes where the bittern now booms, and the heron stands alone for hours watching the water, while the tufted plover wails above its head, the wild-fowl shooter glides along noiseless as a ghost in his punt, pulling it on by clutching the over-hanging reeds, for the sound of a paddle would startle the whole flock, and he would never come within shot but for this guarded silence. He bears the beating rain and the hard blowing winds of February without a murmur, for he knows the full-fed mallard-feathered like the richest green velvet-and the luscious teal will be his reward, if he perseveres and is patient. In the midnight moonlight, and the grey dawn of morning, he is out on those silent waters, when the weather almost freezes his very blood, and he can scarcely feel the trigger that he draws; while the edges of frosted water-flags which he clutches, to pull his punt along, seem to cut like swords. To us there has seemed to be at such times 'a Spirit brooding on the waters,' a Presence felt more in those solitudes than ever falls upon the heart amid the busy hum of crowded cities, which has caused us to exclaim unawares, 'God is here!' Butterflies that have found a hiding-place some-where during winter again appear, and begin to lay their eggs on the opening buds, which when in full leaf will supply food for the future cater-pillars. Amongst these may now be found the new-laid eggs of the peacock and painted-lady butterflies, on the small buds of young nettles, though the plants are only just above ground. Everybody who has a garden now begins to make some little stir in it, when the weather is fine, for the sweet air that now blows abroad mellows and sweetens the newly-dug earth, and gives to it quite a refreshing smell. And all who have had experience, know that to let the ground lie fallow a few weeks after it is trenched, is equal to giving it an extra coating of manure, such virtue is there in the air to which it lies exposed. Hard clods that were difficult to break with the spade when first dug up, will, after lying exposed to the sun and frost, crumble at a touch like a ball of sand. It is pleasant, too, to see the little children pottering about the gardens, unconscious that, while they think they are helping, they are in the way of the workmen; to see them poking about with their tiny spades or pointed sticks, and hear their joyous shouts, when they see the first crocus in flower, or find beneath the decaying weeds the upright leaves of the hyacinth. Even the very smallest child, that has but been able to walk a few weeks, can sit down beside a puddle and help to make 'dirt-pies,' while its little frock slips off its white shoulders, and as some helping sister tries to pull it on again, she leaves the marks of her dirty fingers on the little one's neck. But a fire kindled to burn the great heap of weeds which Winter has withered and dried, is their chief delight. What little bare sturdy legs come toddling up, the cold red arms bearing another tiny load which they throw upon the fire, and what a clapping of hands there is, as the devouring flame leaps up and licks in the additional fuel which cracks again as the February wind blows the sparks about in starry showers! Pleasant is it also to watch them beside the village brook, after the icy chains of Winter are unloosened, floating their sticks and bits of wood which they call boats-all our island children are fond of water-while their watchful mothers are sewing and gossiping at the open cottage doors, round which the twined honeysuckles are now beginning to make a show of leaves. All along beside the stream the elder-trees are shewing their emerald buds, while a silvery light falls on the downy catkins of the willows, which the country children call palm; while lower down we see the dark green of the great marsh-marigolds, which ere long will be in flower, and make a golden light in the clear brook, in which the leaves are now mirrored. Happy children! they feel the increasing warmth, and find enjoyment in the lengthening of the days, for they can now play out-of-doors an hour or more longer than they could a month or two ago, when they were bundled off to bed soon after dark,'to keep them,' as their mothers say, 'out of mischief.' Sometimes, while digging in February, the gardener will turn up a ball of earth as large as a moderate-sized apple; this when broken open. will be found to contain the grub of the large stag-beetle in a torpid state. When uncoiled, it is found to be four inches in length. About July it comes out a perfect insect-the largest we have in Britain. Some naturalists assert that it remains underground in a larva state for five or six years, but this has not been proved satisfactorily. Many a meal do the birds now gather from the winter greens that remain in the gardens, and unless the first crop of early peas is protected, all the shoots will sometimes be picked off in a morning or two, as soon as they have grown a couple of inches above ground. The wild wood-pigeons are great gatherers of turnip-tops, and it is nothing unusual in the country to empty their maws, after the birds are shot, and wash and dress the tender green shoots found therein. No finer dish of greens can be placed on the table, for the birds swallow none but the young eye-shoots. Larks will at this season sometimes unroof a portion of a corn-stack, to get at the well-filled sheaves. No wonder farmers shoot them; for where they have pulled the thatch off the stack, the wet gets in, finds its way down to the very foundation, and rots every sheaf it falls through. We can never know wholly, what birds find to feed upon at this season of the year; when the earth is sometimes frozen so hard, that it rings under the spade like iron, or when the snow lies knee-deep on the ground. We startle them from under the sheltering hedges; they spring up from the lowly moss, which remains green all through the winter; we see them pecking about the bark, and decayed hollow of trees; we make our way through the gorse bushes, and they are there: amid withered grass, and weeds, and fallen leaves, where lie millions of seeds, which the autumn winds scattered, we find them busy foraging; yet what they find to feed upon in many of these places, is still to us a mystery. We know that at this season they pass the greater portion of their time in sleep,-another proof of the great Creator's providence,-so do not require so much food as when busy building, and breeding, in spring and summer. They burrow in the snow through little openings hardly visible to human eyes, beneath hedges and bushes, and there they find warmth and food. From the corn-house, stable, or cart-shed, the blackbird comes rushing out with a sound. that startles us, as we enter; for there he finds something to feed upon: while the little robin will even peek at the window frame if you have been in the habit of feeding him. On the plum-tree, before the window at which we are now writing, a robin has taken his stand every day throughout the winter, eyeing us at our desk, as he waited for his accustomed crumbs. When the door was opened and all still, he would hop into the kitchen, and there we have found him perched on the dresser, nor did we ever attempt to capture him. If strangers came down the garden-walk, he never flew further away than the privet-hedge, until he was fed. Generally, as the day drew to a close, he mounted his favourite plum-tree, as if to sing us a parting song. We generally threw his food under a thorny, low-growing japonica, which no cat could penetrate, although we have often seen our own Browney girring and swearing and switching his tail, while the bird was safely feeding within a yard of him. Primroses are now abundant, no matter how severe the Winter may have been. Amid the din and jar of the busy streets of London, the pleasant cry of 'Come buy my pretty primroses' falls cheerfully on the ear, at the close of February. It may be on account of its early appearance, that we fancy there is no yellow flower so delightful to look upon as the delicately-coloured primrose; for the deep golden hue of the celandine and buttercup is glaring when compared with it. There is a beauty, too, in the form of its heart-shaped petals, also in the foliage. Examined by an imaginative eye, the leaves when laid down look like a pleasant green land, full of little hills and hollows, such as we fancy insects-invisible to the naked glance-must delight in wandering over. Such a world Bloom-field pictured as he watched an insect climb up a plantain leaf, and fancied what an immense plain the foot or two of short grass it overlooked must appear in the eye of a little traveller, who had climbed a summit of six inches. In the country they speak of things happening at 'primrose-time:' he died or she was married 'about primrose-time;' for so do they mark the season that lies between the white ridge of Winter, and the pale green border of Spring. Then it is a flower as old and common as our English daisies, and long before the time of Alfred must have gladdened the eyes of Saxon children by its early appearance, as it does the children of the present day. The common coltsfoot has been in flower several weeks, and its leaves are now beginning to appear, for the foliage rarely shews itself on this singular plant until the bloom begins to fade. The black hellebore is also in bloom, and, on account of its resemblance to the queen of summer, is called the Christmas-rose, as it often flowers at that season. It is a pretty ornament on the brow of Winter, whether its deep cup is white or pale pink, and in sheltered situations remains a long time in flower. Every way there are now signs that the reign of Winter is nearly over: even when he dozes he can no longer enjoy his long sleep, for the snow melts from under him almost as fast as it falls, and he feels the rounded buds breaking out beneath him. The flush of golden light thrown from the prim-roses, as they catch the sunshine, causes him to rub his dazed eyes, and the singing of the unloosened meadow-runnels falls with a strange sound on his cold, deadened ear. He knows that Spring is hiding somewhere near at hand, and that all Nature is waiting to break out into flower and song, when he has taken his departure. A great change has taken place almost unseen. We cannot recall the day when the buds first caught our eye-tiny green dots which are now opening into leaves that are covering the lilac-trees. We are amazed to see the hawthorn hedge, which a week or two ago we passed unnoticed, now bursting out into the pale green flush of Spring-the most beautiful of all green hues. We feel the increasing power of the sun; and windows which have been closed, and rendered air-tight to keep out the cold, are now thrown open to let in the refreshing breeze, which is shaking out the sweet buds, and the blessed sunshine-the gold of heaven-which God in His goodness showers alike upon the good and the evil. HISTORICALFebruary was one of the two months (January being the other) introduced into the Roman Calendar by Numa Pompilius, when he extended the year to twelve of these periods. Its name arose from the practice of religious expiation and purification which took place among the Romans at the beginning of this month (Februare, to expiate, to purify). It has been on the whole an ill-used month, perhaps in consequence of its noted want (in the northern hemisphere) of what is pleasant and agreeable to the human senses. Numa let fall upon it the doom which was unavoidable for some one of the months, of having, three out of four times, a day less than even those which were to consist of thirty days. That is to say, he arranged that it should have only twenty-nine days, excepting in leap years; when, by the intercalation of a day between the 23rd and 24th, it was to have thirty. No great occasion here for complaint. But when Augustus chose to add a thirty-first day to August, that the month named from him might not lack in the dignity enjoyed by six other months of the year, he took it from February, which. could least spare it, thus reducing it to twenty-eight in all ordinary years. In our own parliamentary arrangement for the reformation of the calendar, it being necessary to drop a day out of each century excepting those of which the ordinal number could be divided by four, it again fell to the lot of February to be the sufferer. It was deprived of its 29th day for all such years, and so it befell in the year 1800, and will in 1900, 2000, 2100, 2200, &c. Verstegan informs us that, among our Saxon ancestors, the month got the name of Sprout-kale, from the fact, rather conspicuous in gardening, of the sprouting of cabbage at this ungenial season. The name of Sol-monatt was afterwards conferred upon it, in consequence of the return of the luminary of day from the low course in the heavens which for some time he had been running. "The common emblematical representation of February is, a man in a sky-coloured dress, bearing in his hand the astronomical sign Pisces." CHARACTERISTICS OF FEBRUARYThe average temperature of January, which is the lowest of the year, is but slightly advanced in February; say from 40° to 41° Fahrenheit. Nevertheless, while frosts often take place during the month, February is certainly more characterised by rain than by snow, and our unpleasant sensations during its progress do not so much arise from a strictly low temperature, as from the harsh damp feeling which its airs impart. Usually, indeed, the cold is intermitted by soft vernal periods of three or four days, during which the snow-drop and crocus are enabled to present themselves above ground. Gloomy, chilly, rainy days are a prominent feature of the month, tending, as has been observed, to a flooding of the country; and we all feel how appropriate it is that the two signs of the zodiac connected with the month-Aquarius and Pisces-should be of such watery associations. Here, again, however, we are liable to a fallacy, in imagining that February is the most rainy of the months. Its average depth of fall, 4.21 inches, is, in reality, equaled by three other months, January, August, and September, and exceeded by October, November, and December, as shewn by a rain-gauge kept for thirty years in the Isle of Bute. At London, the sun is above the horizon on the 1st of February from 7h. 42m. to 4h. 47m., in all 9h. 5m. At the last day of the month, the sun is above the horizon 10h. 45m. |