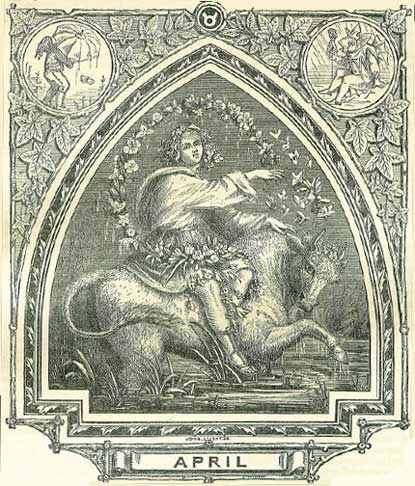

April Next came fresh April, full of lustyhed, And wanton as a kid whose home new buds; Upon a bull he rode, the same which led Europa floating through th' Argolick duds: His horns were gilden all with golden studs, And garnished with garlands goodly sight, Of all the fairest flowers and freshest buds, Which th' earth brings forth; and wet he seemed in sight With waves through which he waded for his love's delight. DESCRIPTIVEApril presents no prettier picture than that of green fields, with rustic stiles between the openings of the hedges, where old footpaths go in and out, winding along, until lost in the distance; with children scattered here and there, singly or in groups, just as the daisies are, all playing or gathering flowers. With what glee they rush about chasing one another in zigzag lines like butterflies, tumbling here, and running there; one lying on its back, laughing and shouting in the sunshine; another, prone on the grass, is pretending to cry, in order to be picked up. A third, a quiet little thing, with her silky hair hanging all about her sweet face, sits patiently sticking daisy-buds on the thorns of a leafless branch, that she may carry home a tree of flowers. Some fill their pinafores, others sit decorating their caps and bonnets, while one, whose fair brow has been garlanded, dances as she holds up the skirt of her little frock daintily with her fingers. Their graceful attitudes can only be seen for a few moments; for if they catch a strange eye directed towards them, they at once cease their play, and start off like alarmed birds. We have often wished for a photograph of such a scene as we have here described and witnessed while sheltered behind some hedge or tree. Dear to us all are those old footpaths that, time out of mind, have gone winding through the pleasant fields, beside hedges and along watercourses, leading to peaceful villages and faraway farms, which the hum and jar of noisy cities never reach; where we seem at every stride to be drawing nearer the Creator, as we turn our backs upon the perishable labours of man. Only watch some old man, bent with the weight of years, walking out into the fields when April greens the ground - 'Making it all one emerald.' With what entire enjoyment he moves along, pausing every here and there to look at the opening flowers! Yes, they are the very same he gazed upon in boyhood, springing from the same roots, and growing in the very spots where he gathered them fifty long years ago. What a many changes he has seen since those days, while they appear unaltered! He thinks how happy life then passed away, with no more care than that felt by the flowers that wave in the breeze and sunshine, which shake the rain from their heads, as ho did when a boy, darting in and out bareheaded, when he ran to play amid the April showers. Tears were then dried and forgotten almost as soon as shed. He recalls the corn-anions of his early manhood, who stood full-caved beside him, in the pride of their summer strength and beauty, shewing no sign of decay, but exulting as if their whole life would be one unchanged summerhood. Where are they now? Some fell with all their leafy honours thick upon them. A few reached the season of the 'sere and yellow leaf' before they fell, and were drifted far away from the spot where they flourished, and which now 'knoweth them no more for ever.' A few stood up amid the silence of the winter of their age, though they saw but little of one another in those days of darkness. And now he recalls the withered and ghastly faces, which were long since laid beneath the snow. He alone is spared to look through the green gates of April down those old familiar footpaths, which they many a time traversed together. 'Cuckoo! cuckoo!' Ah, well he knows that note! It brings again the backward years-the sound he tried to imitate when a boy-home, with its little garden-the very face of the old clock, whose ticking told him it was near schooltime. And he looks for the messenger of spring now as he did then, as it flies from tree to tree; but all he can discover is the green foliage, for his eyes are dim and dazed, and he cannot see it now. He hears the song of some bird, which was once as familiar to him as his mother's voice, and tries to remember its name, but cannot; and as he tries, he thinks of those who were with him when he heard it; and so he goes on unconsciously unwinding link by link the golden chain which reaches from the grave to heaven. And when he returns home, he carries with him a quiet heart, for his thoughts scarcely seem allied to earth, and lie 'too deep for tears.' He seems to have looked behind that gray misty summit, where the forgotten years have rolled down, and lie buried, and to have seen that dim mustering-ground beyond the grave, where those who have gone before are waiting to receive him. Many of the trees now begin to make 'some little show of green.' Among these is the elm, which has a beautiful look with the blue April sky seen through its half-developed foliage. The ash also begins to shew its young leaves, though the last year's 'keys,' with the blackened seed, still hang among the branches, anti rattle again in every wind that blows. The oak puts out its red buds and bright metallic-looking leaves slowly, as if to shew that its hardy limbs require as little clothing as the ancient Britons did, when hoary oaks covered long leagues of our forest-studded island. The chesnut begins to shoot forth its long, finger-shaped foliage, which breaks through the rounded and gummy buds that have so firmly enclosed it. On the limes we see a tender and delicate green, which the sun shines through as if they were formed of the clearest glass. The beech throws from its graceful sprays leaves which glitter like emeralds when they are steeped in sunshine; and no other tree has such a smooth and beautiful bark, as rustic lovers well know when they carve the names of their beloved ones on it. The silver birch throws down its flowers in waves of gold, while the leaves drop over them in the most graceful forms, and the stem is clashed with a variety of colours like a bird. The laburnums stand up like ancient foresters, clothed in green and gold. But, beautiful above all, are the fruit-trees, now in blossom. The peaches seem to make the very walls to which they are trailed burn again with their bloom, while the cherry-tree looks as if a shower of daisies had rained it, and adhered to the branches. The plum is one mass of unbroken blossom, without shewing a single green leaf, while, in the distance, the almond-tree looks like some gigantic flower, whose head is one tuft of bloom, so thickly are the branches embowered with buds. Then come the apple-blossoms, the loveliest of all, looking like a bevy of virgins peeping out of their white drapery, covered with blushes; while all the air around is per-fumed with the fragrance of the bloom, as if the winds had been out gathering flowers, and scattered the perfume everywhere as they passed. All day long the bees are busy among the bloom, making an unceasing murmur, for April is beautiful to look upon; and if she hides her sweet face for a few hours behind the rain-clouds, it is only that she may appear again peeping out through the next burst of sunshine in a veil of fresher green, through which we see the red and white of her bloom. Numbers of birds, whose names and songs are familiar to us, have, by the end of this month, returned to build and sing once more in the bowery hollows of our old woods, among the bushes that dot our heaths, moors, and commons, and in the hawthorn-hedges which stretch for weary miles over green Old England, and will soon be covered with May-buds. We find the 'time of their coming' mentioned in the pages of the Bible, shewing that they migrated, as they do now, and were noticed by the patriarchs of old, as they led their flocks to the fresh spring-pastures. The sand-marten-one of the earliest swallows that arrives-sets to work like a miner, making a pick-axe of his beak, and hewing his way into the sandbank, until he hollows out for himself a comfortable house to dwell in, with a long passage to it, that goes sloping upward to keep out the wet, and in which he is caverned as dry and snug as ever were our painted forefathers. The window-swallow is busy building in the early morning,-we see his shadow darting across the sunny window-blind while we are in bed.; and if we arise, and look cautiously through one corner of the blind, we see it at work, close to us, smoothing the clay with its throat and the under part of the neck, while it moves its little head to and fro, holding on to the wall or window-frame all the time by its claws, and the flattening pressure of the tail. It will soon get accustomed to our face, and go on with its work, as if totally unconscious of our presence, if we never wilfully frighten it. Other birds, like hatters, felt their nests so closely and solidly together, that they are as hard to cut through as a well-made mill-board. Some fit the materials carefully together, bending one piece and breaking another, and making them fit in everywhere like joiners and carpenters, though they have neither square, nor rule, nor tool, only their tiny beaks, with which they do all. Some weave the materials in and out, like basket-makers; and by some unknown process-defying all human ingenuity-they will work in, and bend to suit their purpose, sticks and other things so brittle and rotten that were we only to touch them ever so gently, they would drop to pieces. Nothing seems to come amiss to them in the shape of building materials, for we find their nests formed of what might have been relics of mouldering scarecrows, bits of old hats, carpets, wool-stockings, cloth, hair, moss, cotton in rags and hanks, dried grass, withered leaves, feathers, lichen, decayed wood, bark, and we know not what beside; all put neatly together by these skilful and cunning workmen. They are the oldest miners and masons, carpenters and builders, felters, weavers, and basket-makers; and the pyramids are but as the erections of yesterday compared with the time when these ancient architects first began to build. As for their nests: What nice hand, With every implement and means of art, And twenty years' apprenticeship to boot, Could make us such another? Amongst the arrivals in April is the redstart, which is fond of building in old walls and ruins. Where the wild wallflower waves from some crumbling castle, or fallen monastery, there it is pretty sure to be seen, perched perhaps on the top of a broken arch, constant at its song from early morn, and shaking its tail all the time with a tremulous motion. We also recognise the pleasant song of the titlark, or tree-pipit, as it is often called; and peeping about, we see the bird perched on some topmost branch, from which it rises, singing, into the air a little way up, then descends again, and perches on the same branch it soared from, never seeming at rest. We also see the pretty whitethroat, as it rises up and down, alighting a score times or more on the same spray, and singing all the time, seeming as if it could neither remain still nor be silent for a single minute on any account. Sometimes it fairly startles you, as it darts past, its white breast flashing on the eye like a sudden stream of light. Country children, when they see it, call out: Pretty Peggy Whitethroat, Come stop and give us a note. The woodlark is another handsome-looking bird, that sings while on the wing as well as when perched on some budding bough, though its song is not so sweet as that of Shakspeare's lark, which: 'At heaven's gate sings.' Then there are the linnets, that never leave us, but only shift their quarters from one part of the country to another, loving most to congregate about the neighbourhood of gorse-bushes, where they build and sing, and live at peace among the thousands of bees that are ever coining to look for honey in the golden baskets which hang there in myriads. We hear also the pretty goldfinch, that is marked with black and white, and golden brown; and pleasant it is to watch a couple of' them, tugging and tearing at the same head of groundsel. But all the land is now musical: the woods are like great cathedrals, pillared with oaks and roofed with the sky, from which the birds sing, like hidden nuns, in the green twilight of the leafy cloisters. Now the angler hunts up his fishing-tackle, for the breath of April is warm and gentle; a golden light plays upon the streams and rivers, and when the rain comes down, it seems to tread with muffled feet on the young leaves, and hardly to press down the flowers. But to hear the sweet birds sing, to feel the refreshing air blowing gently on all around, and see Nature arraying herself in all her spring beauty, has ever seemed to us a much greater pleasure than that of fishing. Few care about reading the chapters in delightful old Izaak Walton, that treat upon fishes alone: it is when he quits his rod and line, and begins to gossip about the beauty of the season; when he sits upon that primrose bank, and tells us that the meadows 'are too pleasant to be looked at but only on holidays; ' making, while so seated, 'a brave breakfast with a piece of powdered beef, and a radish or two he has in his bag,'-that we love most to listen to him. Still, angling is of itself a pleasant out-of-door sport; for, if tired, there is the bank ready to sit down upon; the clear river to gaze over; the willows to watch as they ever wave wildly to and fro; or the circle in the water-made by some fish as it rises at a fly-to trace, as it rounds and widens, and breaks among the pebbles on the shore, or is lost amid the tangles of the overhanging and ever-moving sedge. Then comes the arrowy flight of the swallows, as they dart after each other through the arch of the bridge, or dimple the water every here and there as they sweep over it. Ever shifting our position, we can 'dander' along, where little curves and indentations form tiny bays and secluded pools, which, excepting where they open out riverward, are shut in by their own overhanging trees and waving sedges. Or, walking along below the embankment, we come to the great sluice-gates, that are now open, and where we can see through them the stream that runs between far-away meadows where all is green, and shadows are thrown at noonday over the haunts of the water-hen and water-rat. Saving the lapping of the water, all is silent. There a contemplative man may sit and hold communion with Nature, seeing something new every time he shifts his glance, for many a flower has now made its appearance which remained hidden while March blew his windy trumpet, and in these green moist shady places the blue bell of spring may now be found. It is amongst the earliest flowers-such as the cow-slips and daisies-that country children love to place the bluebell, to ornament many an open cottage-window in April; it bears no resemblance to the blue harebell of summer, as the latter flowers grow singly, while those of the wild hyacinth nearly cover the stem with their closely-packed bells, sometimes to a foot in height. The bells, which are folded, are of a deeper blue than those that have opened; and very grace-fully do those hang down that are in full bloom, shewing the tops of their fairy cups turning backward. The dark upright leaves are of a beautiful green, and attract the eye pleasantly long before the flowers appear. Beside them, the delicate lily-of-the-valley may also now be found, one of the most graceful of all our wild-flowers. How elegantly its white ivory-looking bells rise, tier above tier, to the very summit of the flower-stalk, while the two broad leaves which protect it seem placed there for its support, as if a thing of such frail beauty required something to lean upon! Those who have inhaled the perfume from a whole bed of these lilies in some open forest-glade, can fancy what odours were wafted through Eden in the golden mornings of the early world. At the end of the month, cowslips are sprinkled plentifully over the old deep-turfed pastures in which they delight to grow, for long grass is unfavourable to their flowering, and in it they run all to stalk. What a close observer of flowers Shakspeare must have been, to note even the 'crimson drops i' th' bottom' of the cowslip, which he also calls 'cinque-spotted!' The separate flowers or petals are called 'peeps ' in the country, and these are picked out to make cowslip wine. We have counted as many as twenty-seven flowers on one stalk, which formed a truss of bloom larger than that of a verbena. A pile of cowslip 'peeps,' in a clean basket, with a pretty country child, who has gathered them and brought them for sale, is no uncommon sight at this season in the market-place of some old-fashioned country town. The gaudy dandelion and great marsh-marigold are now in flower, one lighting up our wayside wastes almost every-where, and the other looking like a burning lamp as its reflection seems blazing in the water. It is pleasant to see a great bed of tall dandelions on a windy April day shaking all their golden heads together; and common as it may appear, it is a beautiful compound flower. And who has not, in the days of childhood, blown off the downy seed, to tell the hours of the day by the number of puffs it took to disperse the feathered messengers? How beautifully, too, the leaves are cut! and when bleached, who does not know that it is the most wholesome herb that ever gave flavour to a salad? Shakspeare's- Lady-smock all silver white,' - is also now abundant in moist places, still retaining its old name of 'cuckoo-flower,' though we know that several similar flowers are so called in the country through coming into bloom while the cuckoo sings. The curious arum or cuckoo-pint, which children call ' lords and ladies,' in the midland counties, is now found under the hedges. Strip off the spathe or hood, and inside you will find the 'parson-in-his-pulpit,' for that is another of its strange country names. Few know that this changing plant, with its spotted leaves, forms those bright coral-berries which give such a rich colouring to the scenery of autumn. It must have furnished matter of mirth to our easily pleased forefathers, judging from the many merry names they gave to it, and which are still to be found in our old herbals. Leaves, also, are beautiful to look upon without regarding the exquisite forms and colours of the flowers; and strange are the names our botanists have been compelled to adopt to describe their different shapes. Awl, arrow, finger, hand, heart, and kidney-shaped are a few of the names in common use for this purpose. Then the margin or edges of leaves are saw-toothed, crimped, smooth, slashed, notched, torn out, and look even as if some of them have been bitten by every variety of mouth; as if hundreds of insects had been at work, and each had eaten out its own fanciful pattern. Others, again, are armed, and have a 'touch-me-not' look about them, like those of the holly and thistles; while some are covered underneath with star-shaped prickles, hair-like particles, or soft down, making them, to the touch, rough, smooth, sticky, or soft as the down of velvet. To really see the form of a leaf, it must be examined when all the green is gone and only the skeleton left, which shews all the ribs and veins that were before covered. A glass is required to see this exquisite workmanship. The most beautiful lace is poor in comparison with the patterns which Nature weaves in her mysterious loom; and skilful lace-makers say, that no machine could be made to equal the beautiful patterns of the skeleton leaves, or form shapes so diversified. Spring prepares the drapery which she hangs up in her green halls for the birds to shelter and build and sing among; and soon the hawthorn will light tip these hanging curtains with its silver lamps, and perfume the leafy bowers with May. In a work entitled The Twelve Moneths, published in 1661, April is described with a glow of language that recalls the Shaksperian era: The youth of the country make ready for the morris-dance, and the merry milkmaid supplies them with ribbons her true love had given her. The little fishes lie nibbling at the bait, and the porpoise plays in the pride of the tide. The shepherds entertain the princes of Arcadia with pleasant roundelays. The aged feel a kind of youth, and youth hath a spirit fall of life and activity; the aged hairs refreshen, and the youthful cheeks are as red as a cherry. The lark and the lamb look up at the sun, and the labourer is abroad by the dawning of the day, The sheep's eye in the lamb's head tells kind-hearted maids strange tales, and faith and troth make the true-lover's knot. It were a world to set down the worth of this month; for it is Heaven's blessing and the earth's comfort. It is the messenger of many pleasures, the courtier's progress, and the farmer's profit; the labourer's harvest, and the beggar's pilgrimage. In sum, there is much to be spoken of it; but, to avoid tediousness, I hold it, in all that I can see in it, the jewel of time and the joy of nature. Hail April, true Medea of the year, That makest all things young and fresh appear, What praise, what thanks, what commendations due, For all thy pearly drops of morning dew? When we despair, thy seasonable showers Comfort the corn, and cheer the drooping flowers; As if thy charity could not but impart A shower of tears to see us out of heart. Sweet, I have penned thy praise, and here I bring it, In confidence the birds themselves will sing it. HISTORICALIn the ancient Alban calendar, in which the year was represented as consisting of ten months of irregular length, April stood first, with thirty-six days to its credit. In the calendar of Romulus, it had the second place, and was composed of thirty days. Numa's twelve-month calendar assigned it the fourth place, with twenty-nine days; and so it remained till the reformation of the year by Julius Cesar, when it recovered its former thirty days, which. it has since retained. It is commonly supposed that the name was derived from the Latin, aperio, I open, as marking the time when the buds of the trees and flowers open. If this were the case, it would make April singular amongst the months, for the names of none of the rest, as designated in Latin, have any reference to natural conditions or circumstances. There is not the least probability in the idea. April was considered amongst the Romans as Venus's month, obviously because of the reproductive powers of nature now set agoing in several of her departments. The first day was specially set aside as Festum Veneris et Fortunae Virilis. The probability, therefore, is, that Aprilis was Aphrilis, founded on the Greek name of Venus (Aphrodite). Our Auglo-Saxon forefathers called the monthOster-monath; and for this appellation the most plausible origin assigned is-that it was the month during which east winds prevailed. The term Easter may have come from the same origin. CHARACTERISTICS OF APRILIt is eminently a spring month, and in England some of the finest weather of the year occasionally takes place in April. Generally, however, it is a month composed of shower and sunshine rapidly chasing each other; and often a chill is communicated by the east winds. The sun enters Taurus on the 20th of the month, and thus commences the second month past the equinox. At the beginning of April, in London, the sun rises at 5:33 A.M., and sets at 6:27 P.M.; at the end, the times of rising and setting are 4:38 and 7:22. The mean temperature of the air is 49.9°'. Proverbial wisdom takes, on the whole, a kindly view of this flower-producing month. It even asserts that - A cold April The barn will fill. The rain is welcomed: An April flood Carries away the frog and his brood. And April showers Make May flowers. Nor is there any harm in wind: When April blows his horn, It's good for both hay and corn. AN APRIL DAY This day Dame Nature seemed in love; The lusty sap began to move; Fresh juice did stir th' embracing vines, And birds had drawn their valentines. The jealous trout that low did lie, Rose at a well-dissembled fly; Already were the eaves possess'd With the swift pilgrim's daubed nest: The groves already did rejoice, In Philomel's triumphing voice: The showers were short, the weather mild, The morning fresh, the evening smiled. Joan takes her neat-rubbed pail, and now She trips to milk the sand-red cow. The fields and gardens were beset With tulips, crocus, violet; And now, though late, the modest rose Did more than half a blush disclose. Thus all looks gay and full of cheer, To welcome the new-liveried year. |