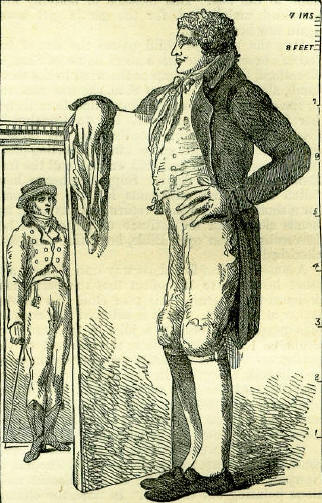

8th SeptemberBorn: Lodovico Ariosto, Italian poet, 1474, Reggio, in Lombardy; John Leyden, poet, 1775, Denholm, Roxburghshaire. Died: Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, murdered at Calais, 1397; Amy Robsart, wife of the Earl of Leicester, 1560, Cumnor; Francis Quarles, poet, 1644; Princess Elizabeth, daughter of Charles I, 1650, Carisbrooke Castle; Bishop Joseph Hall, author of the Contemplations and Satires, 1656, Higham, near Norwich. Feast Day: The Nativity of the blessed Virgin. St. Adrian, martyr. St. Sidreinns, martyr, 3rd century. Saints Eusebius, Nestablus, Zeno, and Nestor, martyrs, 4th century. St. Disen or Disibode, bishop and confessor, about 700. St. Corbinian, bishop of Frisingen, confessor, 730. The Holy Name of the Blessed Virgin Mary. LODOVICO ARIOSTOThe author of Orlando Furioso was born at the castle of Reggio, in Lombardy, on the 8th of September 1474. Of all the Italian poets, he is considered to be the most eminent, and his name is held in the same veneration in his native country as that of Shakspeare is in England. Preferring comfort and independence to splendour and servility, he refused several invitations to live at the courts of crowned heads, and built a commodious, but small house, for his own residence, at Ferrara. Being asked how he, who had described so many magnificent palaces in his poems, could be satisfied with so small a house, he replied that it was much easier to put words and sentences together than stones and mortar. Then leading the inquirer to the front of his house, he pointed out the following inscription on the lintel below the windows, extending along the whole front of the house. Parva sed apta mihi, sed nulli obnoxia, sed non Sordida, parta meo sod tamen aere domus. Which may be translated Small is my humble roof, but well designed To suit the temper of the master's mind; Hurtful to none, it boasts a decent pride, That my poor purse the modest cost supplied. Ferrara derives its principal celebrity from the house of Ariosto, which is maintained in good condition at the public expense. The first edition of the Orlando was published in that city in 1516, and there, too, the poet died and was buried in the Benedictine Church, in 1533. Some time in the last century, the tomb of Ariosto was struck by lightning, and the iron laurels that wreathed the brows of the poet's bust were melted by the electric fluid. And so Byron tells us: The lightning rent from Ariosto's bust The iron crown of laurels' mimick'd leaves; Nor was the ominous element unjust, For the true laurel wreath, which glory weaves, Is of the tree no bolt of thunder cleaves, And the false semblance but disgraced his brow; Yet still, if fondly superstition grieves, Know that the lightning sanctifies below, Whate'er it strikes-Yon head is doubly sacred now. In 1801, the French general, Miollis, removed Ariosto's tomb and remains to the gallery of the public library of Ferrara; and there, too, are pre-served his chair, ink-stand, and an imperfect copy of the Orlando in his own handwriting. THE DEATH OF THOMAS, DUKE OF GLOUCESTER, 1397The arrest and murder of Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, is one of the most tragical episodes of English history. However guilty he might be, the proceedings against him were executed with such treachery and cruelty, as to render them revolting to humanity. He was the seventh and youngest son of Edward III, and consequently the uncle of Richard II. Being himself a resolute and warlike man, he was dissatisfied with what he considered the unprincipled and pusillanimous conduct of his nephew, and, either from a spirit of patriotism or ambition, or, more probably, a combination of both, he promoted two or three measures against the king, more by mere words than by acts. On confessing this to the king, and expressing his sorrow for it, he was promised forgiveness, and restored to the royal favour. Trusting to this reconciliation, he was residing peaceably in his castle at Pleshy, near London, where be received a visit from the king, not only without suspicion, but with the fullest confidence of his friendly intentions. The incident is thus touchingly related by Froissart, a contemporary chronicler: The king went after dinner, with part of his retinue, to Fleshy, about five o'clock. The Duke of Gloucester had already supped; for he was very sober, and sat but a short time at table, either at dinner or supper. He came to meet the king, and honoured him as we ought to honour our lord, so did the duchess and her children, who were there. The king entered the hall, and thence into the chamber. A table was spread for the king, and he supped a little. He said to the duke: 'Fair uncle! have your horses saddled: but not all; only five or six; you must accompany me to London; we shall find there my uncles Lancaster and York, and I mean to be governed by your advice on a request they intend making to me. Bid your maitre-d'hotel follow you with your people to London.' The duke, who thought no ill from it, assented to it pleasantly enough. As soon as the king had supped, and all were ready, the king took leave of the duchess and her children, and mounted his horse. So did the duke, who left Fleshy with only three esquires and four varlets. They avoided the high-road to London, but rode with speed, conversing on various topics, till they came to Stratford. The king then pushed on before him, and the earl marshal came suddenly behind him, with a great body of horsemen, and springing on the duke, said: 'I arrest you in the king's name!' The duke, astonished, saw that he was betrayed, and cried with a loud voice after the king. I do not know if the king heard him or not, but he did not return, but rode away. The duke was then hurried off to Calais, where he was placed in the hands of some of the king's minions, under the Duke of Norfolk. Two of these ruffians, Serle, a valet of the king's, and Franceys, a valet of the Duke of Albemarle, then told the Duke of Gloucester, that 'it was the king's will that he should die. He answered, that if it was his will, it must be so. They asked him to have a chaplain, he agreed, and confessed. They then made him lie down on a bed; the two valets threw a feather-bed upon him; three other persons held down the sides of it, while Serle and Franceys pressed on the mouth of the duke till he expired, three others of the assistants all the while on their knees weeping and praying for his soul, and Halle keeping guard at the door. When he was dead, the Duke of Norfolk came to them, and saw the dead body. The body of the Duke of Gloucester was conveyed with great pomp to England, and first buried in the abbey of Pleshy, his own foundation, in a tomb which he himself had provided for the purpose. Subsequently, his remains were removed to Westminster, and deposited in the king's chapel, under a marble slab inlaid with brass. Immediately after his murder, his widow, who was the daughter of Humphry de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, became a nun in the abbey of Barking; at her death she was buried beside her husband in Westminster Abbey. Gower, in his work entitled Vox Claumantis, has a Latin poem on the Duke of Gloucester, in which occur the following lines respecting the manner of his death: Hen quam tortorum quidam de sorte malornm, Sic Ducis electi plumarum pondere lecti, Corpus quassatum jugulantque necant jugnlatum. QUARLES AND HIS EMBLEMSFrancis Quarles, who, at one time, enjoyed the post of 'chronologer to the city of London,' and is supposed to have had a pension from Charles I, has a sort of side-place in English literature in consequence of his writing a book of Emblems, delighted in by the common people, but despised by the learned and the refined. The Protestantism of the first hundred and fifty years following upon the Reformation took a strong turn in favour of hour-glasses, cross-bones, and all other things which tended to make humanity sensible of its miserable defects, and its deplorable destinies. There was quite a tribe of churchyard poets, who only professed to be great in dismal things, and of whom we must presume that they never smiled or joked, or condescended to be in any degree happy, but spent their whole lives in conscientiously making other people miserable. The emblematists were of this order. It was their business to get up little allegorical pictures, founded on some of the distressing characteristics of mortality, carved on wood blocks in the most unlovely style, and accompanied by verses of such harshness as to set the moral teeth on edge, and leave a bitter ideal taste in the mouth for some hours after. An extract of a letter from Pope to Bishop Atterbury, in which he refers to Quarles's work, will give some idea of the system practised by this grim class of preachers: 'Tinnit, inane est' [It rings, and is empty], with the picture of one ringing on the globe with his finger, is the best thing that I have the luck to remember in that great poet Quarles (not that I forget the Devil at Bowls, which I know to be your lordship's favourite cut, as well as favourite diversion). But the greatest part of them are of a very different character from these: one of them, on, 'O wretched man that I am, who shall deliver me from the body of this death!' represents a man sitting in a melancholy posture, in a large skeleton. Another, on, 'O that my head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears!' exhibits a human figure, with several spouts gushing from it, like the spouts of a fountain.' Mr. Grainger, quoting this from Pope, adds: 'This reminds me of an emblem, which I have seen in a German author, on Matt. vii. 3, in which are two men, one of whom has a beam almost as big as himself with a peaked end sticking in his left eye; and the other has only a small hole sticking in his right. Hence it appears that metaphor and allegory, however beautiful in themselves, will not always admit of a sensible representation.' There is just this to be said of Quarles, that he had a vein of real poetry in him, and so far was not rightly qualified for the duty of depressing the spirits of his fellow-creatures. One is struck, too, by hearing of him a fact so like natural and happy life, as that he was the father of eighteen children by one wife. A vine would be her proper emblem, we may presume. His end, again, was duly sad. A false accusation, of a political nature, was brought against him, and he took it so much to heart, that he said it would be his death, which proved true. He died at the age of fifty-two. Quarles's Emblems was frequently printed in the seventeenth century, for the use of the vulgar, who generally rather like things which remind them that, in some essential respects, the great and the cultured are upon their own level. After more than a century of utter neglect, it was reprinted about fifty years ago; and this reprint has also now become scarce. THE PRINCESS ELIZABETH STUARTElizabeth, the second of the ill-fated daughters of the ill-fated Charles I, was born in 1635, in the palace of St. James. The states of Holland, as a congratulatory gift to her father, sent ambergris, rare porcelain, and choice pictures. Scarcely was the child six years old, when the horrors of civil war separated her from her parents, and the remaining nine years of her short life were passed in the custody of strangers. A few interviews with her father cheered those dreary years, and then the last sad meeting of all took place, the day preceding the ever-memorable 30th of January. With attempts at self-control far beyond her tender years, she listened to the last words she ever was to hear from parental lips. The king, we are told, took her in his arms, embraced her, and placing her on his knees, soothed her by his caresses, requesting her to listen to his last instructions, as he had that to confide to her ears which he could tell no one else, and it was important she should hear and remember his words. Among other things, he told her to tell her mother that his thoughts never strayed from her, and that his love should be the same to the last. This message of undying love remained undelivered, for the gentle girl never again saw her mother. How the wretched child passed the day of her father's execution in the ancient house of Sion, at Brentford, God, who tempers the wind to the shorn lamb, alone knows. From Sion, she was removed to the classic shades of Penshurst, and from thence her jealous custodians sent her to Carisbrooke Castle. About eighteen months after her father's death, she accidentally got wet in the bowling-green of the castle; fever and cold ensued, and the frail form succumbed to death. Supposing her to have fallen asleep, her attendants left the apartment for a short time; on their return, she was dead, her hands clasped in the attitude of prayer, and her face resting on an open Bible, her father's last and cherished gift. A statement has found its way into Hume's and other histories, to the effect that the parliament designed to apprentice this poor child to a button-maker at Newport. But it is believed that such an idea never went beyond a joke in the mouth of Cromwell; in point of fact, the conduct of the parliament towards the little princess was humane and liberal, excepting in the matter of personal restraint. At the time of her death, she had an allowance of £1000 per annum for her maintenance; and she was treated with almost all the ceremonious attendance due to her rank. Her remains were embalmed, and buried with considerable pomp, in the church of St. Thomas, at Newport. The letters E. S., on an adjacent wall, alone pointing out the spot. In time, the obscure resting-place of a king's daughter was forgotten; and it came upon people like a discovery, when, in 1793, while a grave was being prepared for a son of Lord de la Warr, a leaden coffin, in excellent preservation, was found, bearing the inscription: Elizabeth, 2nd daughter of the late King Charles. Deceased September 8th MDCL Clarendon says that the princess was a 'lady of excellent parts, great observation, and an early understanding.' Fuller, speaking of her in his quaint style, says: ' The hawks of Norway, where a winter's day is hardly an hour of clear light, are the swiftest of wing of any fowl under the firmament, nature teaching them to bestir themselves to lengthen the shortness of the time with their swiftness. Such was the active piety of this lady, improving the little life allotted to her, in running the way of God's commandments.' The church at Newport becoming ruinous, it was found necessary to rebuild it a few years ago; and her Majesty the Queen, with the sympathy of a woman and a princess, took the opportunity of erecting a monument to the unhappy Elizabeth. Baron Marochetti was commissioned to execute the work, and well has he performed his task. It represents the princess, lying on a mattress, her cheek resting on an open page of the sacred volume, bearing the words, 'Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.' From the Gothic arch, beneath which the figure reposes, hangs an iron grating with its bars broken asunder, emblematising the prisoner's release by death. Two side-windows, with stained glass to temper the light falling on the monument, have been added by her Majesty's desire. And the inscription thus gracefully records a graceful act: To the Memory of the Princess Elizabeth, Daughter of Charles I, who died at Carisbrooke Castle on Sunday, September 8, 1650, and is interred beneath the Chancel of this Church. This Monument is erected, a token of respect for her Virtues, and of sympathy for her Misfortunes, by Victoria R., 1856. PATRICK COTTER: ANCIENT AND MODERN GIANTSHenrion, a learned French academician, published a work in 1718, with the object of showing the very great decrease, in height, of the human race, between the periods of the creation and Christian era. Adam, he tells us, was one hundred and twenty-three feet nine inches, and Eve one hundred and eighteen feet nine inches and nine lines in height. The degeneration, however, was rapid. Noah reached only twenty-seven, while Abraham did not measure more than twenty, and Moses was but thirteen feet in height. Still, in comparison with those, Alexander was misnamed the Great, for he was no more than six feet; and Julius Caesar reached only to five. According to this erudite French dreamer, the Christian dispensation stopped all further decrease; if it had not, mankind by this time would have been mere microscopic objects. So much for the giants of high antiquity: those of the medieval period may be passed over with almost as slight a notice. Funnam, a Scotsman, who lived in the time of Eugene II, is said to have been more than eleven feet high. The remains of that puissant lord, the Chevalier Rincon, were discovered at Rouen in 1509; the skull held a bushel of wheat, the shin-bone was four feet long, and the others in proportion. The skeleton of a hero, named Bucart, found at Valence in 1705, was twenty-two feet long, and we read of others reaching from thirty to thirty-six feet. But even these last, when in the flesh, were, to use a homely expression, not fit to hold a candle to the proprietor of a skeleton, said to be found in Sicily, which measured three hundred feet in length! Relaters of strange stories not unfrequently throw discredit on their own assertions. With this last skeleton was found his walking-stick, thirty feet in length, and thick as the main-mast of a first-rate. But a walking stick only thirty feet in length for a man who measured three hundred, would be as ridiculously short, as one of seven inches for a person of ordinary stature. Sir Hans Sloane was one of the first who expressed an opinion, that these skeletons of giants were not human remains. This was, at the time, considered rank heresy, and the philosopher was asked if he would dare to contradict the sacred Scriptures. But Cuvier, since then, has fully proved that these so-termed bones of giants were in reality fossil remains of mammoths, megatheriums, mastodons, and similar extinct brutes; and that the giant's teeth' found in many museums, had once graced the jaw-bones of spermaceti whales. Of the ancient giants, it is said that they were mighty men of valour, their strength being commensurate with their proportions. But the modern giants are generally a sickly, knock-kneed, splay-footed, shambling race, feeble in both mental and bodily organisation. Such was Patrick Cotter, who died at Clifton on the 8th September 1804. He was exhibited as being eight feet seven inches in height, but this was simply a showman's exaggeration. A memorial-tablet in the Roman Catholic Chapel, Trenchard Street, Bristol, informs us that: Here lie the remains of Mr. Patrick Cotter O'Brien, a native of Kinsale, in the kingdom of Ireland. He was a man of gigantic stature, exceeding eight feet three inches in height, and proportionably large. Cotter was born in 1761, of poor parents, whose stature was not above the common size. When eighteen years of age, a speculative showman bought him from his father, for three years, at £50 per annum. On arriving at Bristol with his proprietor, Cotter demurred to being exhibited, without some remuneration for himself, besides the mere food, clothing, and lodging stipulated in the contract with his father. The showman, taking advantage of the iniquitous law of the period, flung his recalcitrant giant into a debtor's prison, thinking that the latter would soon be terrified into submission. But the circumstances coming to the ears of a benevolent man, he at once proved the contract to be illegal; and Cotter, being liberated, began to exhibit himself for his own profit, with such success that he earned £30 in three days. Showmen well know the value of fine names and specious assertions. So the plebeian name of Cotter was soon changed to the regal appellation of O'Brien. The alleged descendants of Irish. monarchs have figured in many capacities; the following copy of a hand-bill records the appearance of one in the guise of a giant: Just arrived in Town, and to be seen in a commodious room, at No. 11 Haymarket, nearly opposite the Opera House, the celebrated Irish Giant, Mr. O'Brien, of the kingdom of Ireland, indisputably the tallest man ever shewn; he is a lineal descendant of the old puissant King Brien Boreau, and has in person and appearance all the similitude of that great and grand potentate. It is remarkable of this family, that, however various the revolutions in point of fortune and affiance, the lineal descendants thereof have been favoured by Providence with the original size and stature which have been so peculiar to their family. The gentleman alluded to measures near nine feet high. Admittance, one shilling.  Cotter, alias O'Brien, conducted himself with prudence, and having realised a small competence by exhibiting himself, retired to Clifton, where he died at the very advanced age, for a giant, of forty-seven years. He seems to have had less imbecility of mind than the generality of overgrown persons, but all the weakness of body by which they are characterised. He walked with difficulty, and felt considerable pain when rising up or sitting down. Previous to his death, he expressed great anxiety lest his body should fall into the hands of the anatomists, and gave particular directions for securing his remains with brickwork and strong iron bars in the grave. A few years ago, when some alterations were being made in the chapel where he was buried, it was found that his grave had not been disturbed. Cotter probably adopted the name of O'Brien, from a giant of a somewhat similar appellation, who attracted a good deal of attention, and died about the time the former commenced to exhibit. This person's death is thus recorded in the British Magazine for 1783. 'In Cockspur Street, Charing Cross, aged only twenty-two, Mr. Charles Byrne, the famous Irish Giant, whose death is said to have been precipitated by excessive drinking, to which he was always addicted, but more particularly since his late loss of almost all his property, which he had simply invested in a single bank-note of £700. In his last moments, he requested that his remains might be thrown into the sea, in order that his bones might be removed far out of the reach of the chirurgical fraternity; in consequence of which the body was put on board a vessel, conveyed to the Downs, and sunk in twenty fathoms water. Mr. Byrne, about the month of August 1780, measured exactly eight feet; in 1782, his stature had gained two inches; and when dead, his full length was eight feet four inches.' Another account states that Byrne, apprehensive of being robbed, concealed his bank-note in the fireplace on going to bed, and a servant lighting a fire in the morning, the valuable document was consumed. There is no truth in the statement that his remains were thrown into the sea, for his skeleton, measuring seven feet eight inches, is now in the museum of the College of Surgeons. And the tradition of the college is, that the indefatigable anatomist, William Hunter, gave no less a sum than five hundred pounds for Byrne's body. The skeleton chews that the man was very 'knock-kneed,' and the arms are relatively shorter than the legs. Byrne certainly created considerable sensation during the short period he was exhibited in London. In 1782, the summer pantomime, at the Haymarket Theatre-for there were summer pantomimes in those days-was entitled, in reference to Byrne, Harlequin Teague, or The Giant's Causeway! In the museum of Trinity College, Dublin, there is preserved the skeleton of one Magrath, who is said to have attained the height of seven feet eight inches. A most absurd story is related of this person in a Philosophical Survey of Ireland, written by a Dr. Campbell, who gravely states that Magrath's over-growth was the result of a course of experimental feeding from infancy, carried out by the celebrated philosopher Berkeley, bishop of Cloyne. The truth of the matter is, Magrath, at the age of sixteen, being then more than six feet in height, had, probably by his abnormal growth, lost the use of his limbs, and the charitable prelate, concluding that a change from the wretched food of an Irish peasant would be beneficial to the overgrown lad, caused him to be well fed for the space of one month, a proceeding which had the desired effect of literally placing the helpless creature on his legs again. This is the sole foundation for the ridiculous and often-repeated story of Bishop Berkeley's experimental giant. It is a remarkable, little-known, but well-established fact, that while giants are almost invariably characterised by mental and bodily weakness, the opposite anomaly of humanity, the dwarfs, are generally active, intelligent, healthy, and long-lived persons. Guy Patin, a celebrated French surgeon, relates that, in the seventeenth century, to gratify a whim of the empress of Austria, all the giants and dwarf's in the Germanic empire were assembled at Vienna. As circumstances required that all should be housed in one extensive building, it was feared lest the imposing proportions of the giants would terrify the dwarfs, and means were taken to assure the latter of their perfect freedom and safety. But the result was very different to that contemplated. The dwarfs teased, insulted, and even robbed the giants to such an extent, that the over-grown mortals, with tears in their eyes, complained of their stunted persecutors; and, as a consequence, sentinels had to be stationed in the building, to protect the giants from the dwarfs! |