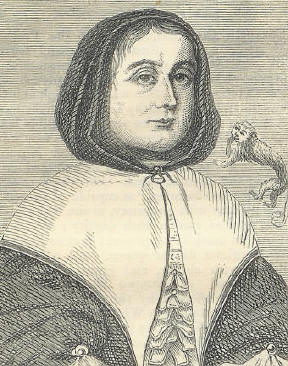

8th OctoberBorn: Dr. John Hoadly, dramatist, 1711, London. Died: Nicolo di Rienzi, tribune of Rome, assassinated, 1354; Sir Richard Blackmore, poet, 1729; Dr. Andrew Kippis, miscellaneous writer, 1795, London; Vittorio Alfieri, great tragic dramatist of Italy, 1803, Florence; Henry Christophe, king of Hayti, 1821; Charles Fourier, Socialist, 1837, Paris; Johann H. Dannecker, German sculptor, 1841, Stuttgart. Feast Day: St.Thais, the penitent, about 348. St. Pelagia, the penitent, 5th century. St. Keyna, virgin, 5th or 6th century. St. Bridget, widow, 1373. RIENZISir E. B. Lytton's noble romance of Rienzi has painted in the most attractive and glowing manner the life and actions of the renowned tribune of Rome. It must be admitted, also, that unlike many so-called historical novelists, the author has little, if at all, overstepped the limits of fact and reality in the portraiture of his hero, and presents, both in the delineation of Rienzi's character and the general picture of the political and social condition of Rome at the period, an account which, making due allowance for poetical embellishment, may, on the whole, be relied on as strikingly just and accurate. It is well known that Rome, in the fourteenth century, was in the most anarchical and deplorable condition. A set of factious and tyrannical nobles had established, in their lawlessness, a perfect reign of terror over the unhappy citizens, and had driven the representatives of St. Peter from their seat in the Eternal City, to establish a new pontifical residence at Avignon, in the south of France. Here, during seventy years of the fourteenth century, the papal court maintained itself, and, freed from the restraints by which it was hemmed in and overawed at home by its own subjects, asserted the privileges of the sacred college and the authority of ecclesiastical sway. In the meantime, the general body of Roman citizens groaned under the oppressions of the nobles, which were every day becoming more frequent and intolerable. This scene of violence was unexpectedly changed by one of the most remarkable revolutions that have ever taken place in any state, and which, if carried out with the same success that inaugurated its commencement, might have exercised a lasting and beneficial influence not only on Rome, but the whole of Italy. Nicolo Gabrini, commonly called Nicole, or Cola di Rienzi, from an abbreviation of his father's name of Lorenzo, was the son of an innkeeper and washerwoman of Rome, who, however, conscious of the natural abilities of their son, bestowed on him a good education, which the young man improved to the best advantage. His enthusiasm was especially excited by the history of the ancient glories of his native city, and he revolved with generous ardour many schemes for raising her from her present degradation to the summit of her primitive greatness. Chosen as one of the thirteen deputies from the Roman commons to the papal government at Avignon, he acquitted himself with great credit in an oration addressed to Pope Clement VI, and received the appointment of apostolic notary, with the daily salary of five gold florins. Stimulated by the success thus achieved, he commenced in earnest, on his return to Rome, his self-imposed task of rousing the citizens to the assertion of their rights and liberties. The death of a much-loved brother, whose assassins, from their aristocratic influence and position, escaped unpunished, added the impulse of revenge to that of patriotism. In animated declamations to the people in the streets and public places of Rome, Rienzi descanted on the greatness of their ancestors, the right and enjoyment of liberty, and the derivation of all law and authority from the will of the governed. The nobles were either too ignorant to comprehend, or too confident in their might, to dread the effect of such addresses, and the designs of the orator were still further veiled by his adopting, like Brutus, the guise of a buffoon or jester, and condescending, in this capacity, to raise a laugh in the palaces of the Roman princes. But, in the month of May 1347, a nocturnal assembly of a hundred citizens was congregated by him on Mount Aventine, and a formal compact was entered into for the re-establishment of the good estate, as Rienzi styled his scheme of popular freedom. A proclamation was then made by sound of trumpet, that on the evening of the following day, all persons should assemble unarmed before the church of St. Angelo. After a night spent in devotional exercises, Rienzi, accompanied by his band of a hundred followers, issued from the church, and marched in a solemn procession to the Capitol, from the balcony of which he harangued the people, and received, in their acclamations, a ratification of his assumption of supreme power. Stephen Colonna, the most formidable of the nobles, was at this time absent from Rome, and on his return to crush out at once and forever, as he imagined, the spark of rebellion, he only narrowly saved himself by flight, from falling a victim to the fury of the populace, who supported with the most determined zeal the cause and authority of their champion. A general order was then issued to the great nobles, that they should peaceably retire from the city to their estates; a command which was obeyed with the most surprising unanimity. The title of tribune of Rome, in remembrance of ancient days, was assumed by Rienzi, who forthwith set himself with active earnestness to the task of administrative reformation. In this, for a time, his endeavours were crowned with the most gratifying and signal success. The defences which the nobles had erected around their palaces, and within which, as in robbers' dens, they ensconced themselves to the defiance of all law and order, were levelled to the ground, and the garrisons of troops by which the citizens were overawed, expelled and suppressed. Law and order were everywhere re-established, an impartial execution of justice insured with respect to all ranks of society, and a rigorous and economical management introduced into the departments of revenue and finance. In these days, according to the glowing account of a historian of the times, quoted by Gibbon, the woods began to rejoice that they were no longer infested with robbers; the oxen began to plough; the pilgrims visited the sanctuaries; the roads and inns were replenished with travellers; trade, plenty, and good faith were restored in the markets; and a purse of gold might be exposed without danger in the midst of the highway. The city and territory of Rome were not the only places comprehended in the patriotic aspirations of Rienzi, who aimed at uniting the whole of Italy into a grand federal republic. In such a scheme, he was five hundred years in advance of his age, and the same difficulties which retarded its accomplishment in modern times, were instrumental in causing its failure in the fourteenth century. The republics and free cities were indeed disposed to look favourably on the projects of the Roman tribune, but the rulers of Lombardy and Naples both despised and hated the plebeian chief. Yet the advice and arbitration of Rienzi were sought by more than one European sovereign, and, as in the case of Cromwell, the aptitude with which he conformed himself to the dignity and general requirements of his high station, formed the theme of universal wonder and applause. But the judgment and solidity which constituted such essential elements in the character of the English Protector, proved deficient with Nicolo di Rienzi. An injudicious and puerile assumption of regal state, some acts of over-severity in the execution of justice, and a tendency to convivial excess, had all their influence, in conjunction with the proverbial fickleness of popular esteem, in bringing about the overthrow of the tribune. On one occasion, when he caused himself to be created a knight with all the ceremonies of chivalry, he excited prodigious scandal by bathing in the sacred porphyry vase of Constantine, whilst at the same time the breaking down of the state bed on which he reposed within the baptistery, the night previous to the performance of the ceremony of investiture, was interpreted as an omen of his approaching downfall. After one or two unsuccessful attempts of the two great factions of the exiled nobles, the Colonna and the Ursini or Orsini, who laid aside their mutual animosities to unite against a common foe, the dethronement of Rienzi was suddenly accomplished by the Count of Minorbino, who introduced himself into Rome at the head of one hundred and fifty soldiers. The tribune, thus surprised, skewed little of the resolution by which his conduct had been hitherto distinguished, and with a lachrymose denunciation of popular ingratitude, he pusillanimously abdicated the government, and was confined for a time in the castle of St. Angelo, from which, in the disguise of a pilgrim, he afterwards contrived to escape. For seven years, Rienzi remained an exile from his native city, wandering about from the court of one sovereign to another, and was at last made a prisoner by the Emperor Charles IV, who sent him as a captive to the papal court at Avignon. The champion of popular rights was for a time treated as a malefactor, and four cardinals were appointed to investigate the charges laid against him of heresy and rebellion. But the magnanimity displayed by him before the pope, seems to have made an impression on the mind of Clement VI, who relaxed the rigours of his confinement by allowing him the use of books, the study of which, more especially of the Holy Scriptures and Titus Livius, served to console the ex-tribune under his misfortunes. On the accession of Innocent VI to the pontificate, a new line of policy was adopted by the court of Avignon, who believed that by sending Rienzi to Rome as its accredited representative, with the title of senator, the anarchy and violence which since his deposition had become more rampant than ever, might be suppressed or diminished. The citizens had, indeed, experienced ample cause for regretting the order and impartiality of Rienzi's sway in the tyranny of his successors. His return was celebrated with every appearance of triumph and rejoicing, and for a short period, the benefits which. had attended his former government marked his resumption of power. But his relations with the court of Avignon rendered him an object of suspicion to the people, whilst a spirit of jealousy and apprehension led him to the perpetration of several acts of cruelty. To crown his unpopularity, the exigencies of government compelled him to impose a tax, and a fatal commotion was the result. In the closing scene of his career, he displayed a strange combination of intrepidity and cowardice, appearing on the balcony of the Capitol, when it was surrounded by a furious multitude, and endeavouring by his eloquence to calm the passions of the mob. A storm of abuse and more effectual missiles interrupted his address, and after being wounded in the hand with an arrow, he seemed to lose all manly resolution, and fled lamenting to an inner apartment. The populace continued to surround the Capitol till the evening, then burst in the doors, and dragged Rienzi, as he was attempting to escape in disguise, to the platform in front of the palace. Here for an hour he stood motionless before the immense multitude, who for a time stood hushed as if by some spell before the man who had undoubtedly in many respects been well deserving of their gratitude. This feeling of affection and remorse might have shielded the tribune, when a man from the crowd suddenly plunged a dagger in his breast. He fell senseless to the ground, and a revulsion taking place in the feelings of the mob, they rushed upon and despatched him with numerous wounds. His body was ignominiously exposed to the dogs, and the mutilated remains committed to the flames. Thus perished the celebrated Rienzi, who in aftertimes has been regarded as the last of the Roman patriots, and celebrated in such glowing language by Lord Byron, with whose lines from Childe Harold's Pilgrimage the present notice may not inappropriately close Then turn we to her latest tribune's name, From her ten thousand tyrants turn to thee, Redeemer of dark centuries of shame- The friend of Petrarch-hope of Italy- Rienzi! last of Romans!While the tree Of freedom's wither'd trunk puts forth a leaf, Even for thy tomb a garland let it be, The Forum's champion, and the people's chief- Her new-born Numa thou-with reign, alas! too brief. JUDICIAL COMBAT BETWEEN A MAN AND A DOGOn 8th October 1361, there took place on the Ile Notre Dame, Paris, a combat, which both illustrates strikingly the maxims and ideas prevalent in that age, and is perhaps the most singular instance on record of the appeals to 'the judgment of God' in criminal cases. M. Aubry de Montdidier, a French gentleman, when travelling through the forest of Bondy, was murdered and buried at the foot of a tree. His dog remained for several days beside his grave, and only left the spot when urged by hunger. The faithful animal proceeded to Paris, and presented himself at the house of an intimate friend of his master's, making the most piteous howlings to announce the loss which he had sustained. After being supplied with food, he renewed his lamentations, moved towards the door, looking round to see whether he was followed, and returning to his master's friend, laid hold of him by the coat, as if to signify that he should come along with him. The singularity of all these movements on the part of the dog, coupled with the nonappearance of his master, from whom he was generally inseparable, induced the person in question to follow the animal. Leading the way, the dog arrived in time at the foot of a tree in the forest of Bondy, where he commenced scratching and tearing up the ground, at the same time recommencing the most piteous lamentations. On digging at the spot thus indicated, the body of the murdered Aubry was exposed to view. No trace of the assassin could for a time be discovered, but after a while, the dog happening to be confronted with an individual, named the Chevalier Macaire, he flew at the man's throat, and could only with the utmost difficulty be forced to let go his hold. A similar fury was manifested by the dog on every subsequent occasion that he met this person. Such an extraordinary hostility on the part of the animal, who was otherwise remarkably gentle and good-tempered, attracted universal attention. It was remembered that he had been always devotedly attached to his master, against whom Macaire had cherished the bitterest enmity. Other circumstances combined to strengthen the suspicions now aroused. The king of France, informed of all the rumours in circulation on this subject, ordered the dog to be brought before him. The animal remained perfectly quiet till it recognised Macaire amid a crowd of courtiers, and then rushed forward to seize him with a tremendous bay. In these days the practice of the judicial combat was in full vigour, that mode of settling doubtful cases being frequently resorted to, as an appeal to the 'judgment of God,' who it was believed would interpose specially to shield and vindicate injured innocence. It was decided by his majesty, that this arbitrament should determine the point at issue, and he accordingly ordered that a duel should take place between Macaire and the dog of the murdered Aubry. We have already explained that the lower animals were frequently, during the middle ages, subjected to trial, and the process conducted against them with all the parade of legal ceremonial employed in the case of their betters. Such an encounter, therefore, between the human and the canine creation, would not, in the fourteenth century, appear either specially extraordinary or unprecedented. The ground for the combat was marked off in the lie Notre Dame, then an open space. Macaire made his appearance armed with a large stick, whilst the dog had an empty cask, into which he could retreat and make his springs from. On being let loose, he immediately ran up to his adversary, attacked him first on one side and then on the other, avoiding as he did so the blows from Macaire's cudgel, and at last with a bound seized the latter by the throat. The murderer was thrown down, and then and there obliged to make confession of his crime, in the presence of the king and the whole court. This memorable combat was depicted over a chimney in the great hall of the chateau of Montargis. The story has been made the subject of a popular melodrama. ELIZABETH CROMWELL: THE LADY PROTECTRESS Elizabeth Cromwell, widow of the Protector, after surviving her illustrious husband fourteen years, died in the house of her son in law, Mr. Claypole, at Norborough, in Northamptonshire, on 8th of October 1672. She was the daughter of Sir James Bourchier, a wealthy London merchant, who possessed a country house and considerable landed estates at Felsted, in Essex. Granger, who would, by no means, be inclined to flatter Elizabeth, admits that she was a woman of enlarged understanding and elevated spirit. 'She was an excellent housewife,' he continues, 'as capable of descending to the kitchen with propriety, as she was of acting in her exalted station with dignity; certain it is, she acted a much more prudent part as Protectress than Henrietta did as queen. She educated her children with ability, and governed her family with address.' A glimpse of the Protectorate household is afforded by the Dutch ambassadors, who were entertained at Whitehall in 1654. After dinner, Cromwell led his guests to another room, then the Lady-Protectress, with other ladies, came to them, and they had 'music, and voices and a psalm.' Heath, in his Flagellum, 'the little, brown, lying book' stigmatised by Carlyle, acknowledges that Cromwell was a great lover of music, and entertained those that were most skilled in it, as well as the proficients in every other science. But this admission is modified by the royalist writer taking care to remind his readers that 'Saul also loved music.' At a period when the vilest scurrility passed for loyalty and wit, we hear no evil report of Elizabeth Cromwell. No doubt her conduct was most carefully watched by her husband's enemies, and the slightest impropriety on her part would have speedily been blazoned abroad; yet no writer of the least authority throws reproach on her fair fame. It may he concluded, then, that though probably plain in person, and penurious in disposition, she was a virtuous, good wife and mother. In Cowley's play, The Cutter of Coleman Street, there is an allusion to her frugal character and want of beauty, where the Cutter, sneeringly describing his friend Worm, says: 'He would have been my Lady-Protectress' poet; he writ once a copy in praise of her beauty; but her highness gave nothing for it, but an old half-crown piece in gold, which she had hoarded up before these troubles, and that discouraged him from any further applications to court.' It is a curious though unexplained fact, that we find none of her relatives taking part in the great civil war, nor even any of them employed under the Protectorate administration of public affairs. Nor has any indisputably genuine portrait of Elizabeth been handed down to us, so that the only representation of her features that we have, though universally considered to be a likeness, is found as the frontispiece of one of the most rare and curious of cookery-books, published in 1664, and entitled The Court and the Kitchen of Elizabeth, commonly called Joan Cromwell, the Wife of the late Usurper, truly Described and Represented. The accompanying illustration is a copy of this singular frontispiece. The reader will notice a monkey depicted at one side of the engraving, and probably may wonder why it was placed there. In explanation, it must be said that the old engravers sometimes indulged in a dry kind of humour, of which this is an example. There is an old vulgar proverb that cannot well be literally repeated at the present day, but its signification is, that on the ground a monkey is passable enough, but the higher it climbs, the more its extreme ugliness becomes apparent. The animal, then, emblematises an ignorant upstart; and as the work is a satire as well as a cookery-book, the monkey is an apposite emblem of one who, according to the author's opinion, 'was a hundred times fitter for a barn than a palace.' From the peculiar style and matter of this book, one is inclined to think that its author had been a master-cook under the royal regime, and lost both his office and perquisites by the altered state of affairs. Or he may have been a discarded servant of Elizabeth herself, for his various observations and anecdotes evince a thorough knowledge of the Protectorate household. Indeed this is the only value the book now possesses, and it must not be forgotten that the only fault or blame implied against Elizabeth by this angry satirist, is her 'sordid frugality and thrifty baseness.' When the Protectress took possession of the palace of Whitehall, our culinary author tells us that 'She employed a surveyor to make her some little labyrinths and trap-stairs, by which she might, at all times, unseen, pass to and fro, and come unawares upon her servants, and keep them vigilant in their places and honest in the discharge thereof Several repairs were likewise made in her own apartments, and many small partitions up and down, as well above stairs as in the cellars and kitchens, her highnessship not being yet accustomed to that roomy and august dwelling, and perhaps afraid of the vastness and silentness thereof. She could never endure any whispering, or be alone by herself in any of the chambers. Much ado she had, at first, to raise her mind and deportment to this sovereign grandeur, and very difficult it was for her to lay aside those impertinent meannesses of her private fortune; like the Bride Cat, metamorphosed into a comely virgin, that could not forbear catching at mice, she could not comport with her present condition, nor forget the common converse and affairs of life. She very providently kept cows in St. James's Park, erected a dairy in Whitehall, with dairy-maids, and fell to the old trade of churning butter and making buttermilk. Next to this covey of milkmaids, she had another of spinsters and sewers, to the number of six, who sat most part of the day in 'her privy chamber sewing and stitching: they were all of them ministers' daughters.' The dishes used at Cromwell's table, of which our author gives the receipts, sufficiently prove that the magnates of the Commonwealth were not insensible to the charms of good living. Scotch collops of veal was a very favourite dish, and marrow puddings were usually in demand at breakfast. The remains, after the household had dined, were alternately given to the poor of St. Margaret's, Westminster, and St. Martin's in the Fields, 'in a very orderly manner without babble or noise.' On great feast-days, Cromwell would call in the soldiers on guard, to eat the relics of his victuals. We are also told, but surely it must be a scullery scandal, that the time honoured perquisite of kitchen-stuff was endangered, under the rule of the Protectress, she wishing to have it exchanged for candles. Nor was she less penurious with her husband's comforts; we are informed that: 'Upon Oliver's rupture with the Spaniards, the commodities of that country grew very scarce, and oranges and lemons were very rare and dear. One day, as the Protector was private at dinner, he called for an orange to a loin of veal, to which he used no other sauce, and urging the same command, was answered by his wife that oranges were oranges now, that crab [Seville] oranges would cost a groat, and, for her part, she never intended to give it.' The reason assigned by the Protectress for 'her frugal inspection and parsimony, was the small allowance and mean pittance she had to defray the household expenses. Yet, she was continually receiving presents from the sectaries; such as Westphalia hams, neats' tongues, puncheons of French wines, runlets of sack, and all manner of preserves and comfits.' It could not he expected that any cook of eminence would serve in such an establishment, and so this chronicler of the backstairs lets us know, that Cromwell's cook was a person of no note, named Starkey, who deservedly came to grief in a very simple manner. One day, when the lord mayor was closeted with the Protector on business of importance, this Starkey, forgetting his high office and professional dignity, took the lord mayor's swordbearer into the cellar, treacherously intending to make that important official drunk and incapable. But Starkey overrated his own prowess, while underrating that of his guest; for the well trained bacchanal of the city was little affected by the peculiar atmosphere of the cellar, while Starkey, becoming drunk and disorderly, was overheard by the Protector, and ignominiously discharged upon the spot. The only state or expense indulged by the Protectress was 'the keeping of a coach, the driver of which served her for caterer, for butler, for serving-man, and for gentleman usher, when she was to appear in any public place.' And our author adds, that she had ' horses out of the army, and their stabling and livery in her husband's allotment out of the Mews, at the charge of the state; so that it was the most thrifty and unexpensive pleasure and divertisement, besides the finery and honour of it, that could be imagined. For it saved many a meal at home, when, upon pretence of business, her ladyship went abroad; and carrying some dainty provant for her own and her daughters' own repast, she spent whole days in short visits, and long walks in the air; so that she seemed to affect the Scythian fashion, who dwell in carts and wagons, and have no other habitations.' The more we read of this scurrilous attack on a prudent mistress, a good wife, and mother, the more we are inclined to admire her true and simple character. It is pleasant to contemplate the Lady-Protectress leaving her palace and banquets of state, to take a long country drive, and a sort of picnic-dinner with her daughters. Nor does our author fail, in some instances, to give her credit for good management; he says that: Her order of eating and meal-times was designed well to the decency and convenience of her service. For, fist of all, at the ringing of a bell, dined the halberdiers, or men of the guard, with the inferior officers. Then the bell rung again, and the steward's table was set for the better sort of those that waited on their highnesses. Ten of whom were appointed to a table ore mess, one of which was chosen by themselves every week for a steward, and he gave the clerk of the kitchen a bill of fare, as was agreed generally every morning. To these ten men, and what friends should casually come to visit them, the value of ten shillings, in what flesh or fish so ever they would have, with a bottle of sack, and two of claret was appointed. But, to prevent after-comers from expecting anything in the kitchen, there was a general rule that if any man thought his business would detain him beyond dinner-time, he was to give notice to the steward of his mess, who would set aside for him as much as his share came to, and leave it in the buttery. The utmost malignity of the royalists, then, could say no more against the Lady-Protectress, than that she was a thrifty housewife, giving her the appellation of Joan, the vulgar phrase for a female servant. And there is every reason to conclude that Elizabeth Cromwell was a wife well worthy of her illustrious partner. |