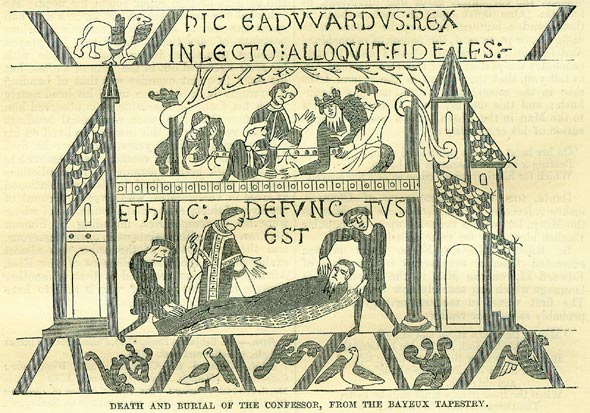

5th JanuaryBorn: Dr. Benjamin Rush, 1745, Philadelphia; Thomas Pringle, traveler and poet, 1789. Died: Edward the Confessor, 1066, Westminster; Catherine de Medicis, Queen of France, 1589; James Merrick, 1769, Reading; John Howie, author of The Scots Worthies, 1793; Isaac Reed, commentator on Shakespeare 1807; Marshal Radetsky, 1858. Feast Day: St. Simeon Stylites, 459; St. Telesphorus, seventh bishop of Rome, 128; St. Syncletica (4th century?), virgin. ST. SIMEON STYLITESSo named from the Greek word stylos, a pillar, was the founder of an order of monks, or rather solitary devotees, called pillar-saints. Of all the forms of voluntary self-torture practised by the early Christians this was one of the most extra-ordinary. Originally a shepherd in Cilicia about the year 408, when only thirteen years of age, Simeon left his flocks, and obtained admission into a monastery in Syria, but afterwards withdrew to a mountain about thirty or forty miles east from Antioch, where he at first confined himself within a circle of stones. Deeming this mode of penance not sufficiently severe, in the year 423 he fixed his residence on the top of a pillar, which was at first nine feet high, but was successively raised to the somewhat incredible height of sixty feet (forty cubits). The diameter of the top of the pillar was only three feet, but it was surrounded by a railing which secured him from falling off, and afforded him some relief by leaning against it. His clothing consisted of the skins of beasts, and he wore an iron collar round his neck. He exhorted the assembled people twice a day, and spent the rest of his time in assuming various postures of devotion. Sometimes he prayed kneeling, sometimes in an erect attitude with his arms stretched out in the form of a cross, but his most frequent exercise was that of bending his meagre body so as to make his head nearly touch his feet. A spectator once observed him make more than 1240 such reverential bendings without resting. In this manner he lived on his pillar more than thirty years, and there he died. in the year 459. His remains were removed to Antioch with great solemnity. His predictions and the miracles ascribed to him are mentioned at large in Theodoretus, who gives an account of the lives of thirty celebrated hermits, ten of whom were his contemporaries, including St. Simeon Stylites. The pillar-saints were never numerous, and the propagation of the order was almost exclusively in the warm climates of the East. Among the names recorded is that of another Simeon, styled the younger, who is said to have dwelt sixty years on his pillar. EDWARD THE CONFESSORTowards the close of 1065, this pious monarch completed the rebuilding of the Abbey at Westminster, and at Christmas he caused the newly-built church to be hallowed in the presence of the nobles assembled during that solemn festival. The king's health continued to decline; and early in the new year, on the 5th of January, he felt that the hand of death was upon him. As he lay, tradition says, in the painted chamber of the palace at Westminster, a little while before he expired, Harold and his kinsman forced their way into the apartment, and exhorted the monarch to name a successor, by whom the realm might be ruled in peace and security. 'Ye know full well, my lords,' said Edward, 'that I have bequeathed my kingdom to the Duke of Normandy, and are there not those here whose oaths have been given to secure his succession? 'Harold stepped nearer, and interrupting the king, he asked of Edward upon whom the crown should be bestowed. 'Harold! take it, if such be thy wish; but the gift will be thy ruin. Against the Duke and his baronage no power of thine can avail thee!' Harold replied that he did not fear the Norman or any other enemy. The dying king, wearied with importunity, turned himself upon his couch, and faintly intimated that the English nation might name a king, Harold, or whom they liked; and shortly afterwards he expired. In the picturesque language of Sir Francis Palgrave, 'On the festival of the Epiphany, the day after the king's decease, his obsequies were solemnised in the adjoining abbey, then connected with the royal abode by walls and towers, the foundations whereof are still existing. Beneath the lofty windows of the southern transept of the Abbey, you may see the deep and blackened arches, fragments of the edifice raised by Edward, supporting the chaste and florid tracery of a more recent age. Westward stands the shrine, once rich in gems and gold, raised to the memory of the Confessor by the devotion of his successors, despoiled, indeed, of all its ornaments, neglected, and crumbling to ruin, but still surmounted by the massy iron-bound oaken coffin which contains the ashes of the last legitimate Anglo-Saxon king.' We long possessed many interesting memorials Of the Confessor in the coronation insignia which he gave to the Abbey Treasury-including the rich vestments, golden crown and sceptres, dalmatic, embroidered pall, and spurs-used at the coronations of our sovereigns, until the reign of Charles II.  The death and funeral of the Confessor are worked in a compartment of the Bayeux Tapestry, believed to be of the age of the Conquest. The crucifix and gold chain and ring were seen in the reign of James II. The sculpures upon the frieze of the present shrine represent fourteen scenes in the life of the Confessor. He was the first of our sovereigns who touched for the king's-evil; he was canonized by Pope Alexander about a century after his death. The use of the Great Seal was first introduced in his reign: the original is in the British Museum. He was esteemed the patron-saint of England until superseded in the 13th century by St. George; he translation of his relics from the old to his new shrine at Westminster, in 1263, still finds a place, on the 13th of October, in the English Calendar: and more than twenty churches exist, dedicated either to him or to Edward the king and martyr. JOHN HOWIEWas author of a book of great popularity in Scotland, entitled the Scots Worthies, being a homely but perspicuous and pathetic account of a select number of persons who suffered for 'the covenanted work of Reformation' during the reigns of the last Stuarts. Howie was a simple-minded Ayrshire moorland farmer, dwelling in a lonely cot amongst bogs, in the parish of Fenwick, a place which his ancestors had possessed ever since the persecuting time, and which continued at a recent period to be occupied by his descendants. His great-grandfather was one of the persecuted people, and many of the unfortunate brethren had received shelter in the house when they did not know where else to lay their head. One friend, Captain Paton, in Meadowhead, when executed at Edinburgh in 1684, handed down his bible from the scaffold to his wife, and it soon after came into the hands of the Howies, who still preserve it. The captain's sword, a flag for the parish of Fenwick, carried at Bothwell Bridge, a drum believed to have been used there, and a variety of manuscripts left by covenanting divines, were all preserved along with the captain's bible, and rendered the house a museum of Presbyterian antiquities. People of great eminence have pilgrimised to Lochgoin to see the home of John Howie and his collection of curiosities, and generally have come away acknowledging the singular interest attaching to both. The simple worth, primitive manners, and strenuous faith of the elderly sons and daughters of John Howie, by whom the little farm was managed, formed a curious study in themselves. Visitors also fondly lingered in the little room, constituting the only one besides the kitchen, which formed at once the parlour and study of the author of the Worthies; also over a bower in the little cabbage-garden, where John used to spend hours-nay, days-in religious exercises, and where, he tells us, he formally subscribed a covenant with God on the 10th of June 1785. A stone in the parish churchyard records the death of the great-grandfather in 1691, and of the grandfather in 1755, the latter being ninety years old, and among the last survivors of those who had gone through the fire of persecution. John Howie wrote a memoir of himself, which no doubt contains something one cannot but smile at, as does his other work also. Yet there is so much pure-hearted earnestness in the man's writings, that they cannot be read without a certain respect. The Howies of Lochgoin may be said to have formed a monument of the religious feelings and ways of a long by-past age, protracted into modern times. We see in them and their cot a specimen of the world of the century before the last. It is to be feared that in a few more years both the physical and the moral features of the place will be entirely changed. ATTEMPTED ASSASSINATION OF LOUIS XVOn the 5th of January 1757, an attempt was made upon the life of the worthless French king, Louis XV., by Robert Francis Damiens. 'Between five and six in the evening, the king was getting into his coach at Versailles to go to the Trianon. A man, who had lurked about the colonnades for two days, pushed up to the coach, jostled the dauphin, and stabbed the king under the right arm with a long knife; but, the king having two thick coats, the blade did not penetrate deep. Louis was surprised, but thinking the man had only pushed against him, said, 'Le coquin m'a donne un furieux coup de poing,' but putting his hand to his side, and feeling blood, he said, 'Il m'a blesse; qu'on le saisisse, et qu'on ne lui fasse point de mal.' The king being carried to bed, it was quickly ascertained that the wound was slight and not dangerous. Damiens, the criminal, appeared clearly to be mad. He had been footman to several persons, had fled for a robbery, had returned to Paris in a dark and restless state of mind; and by one of those wonderful contradictions of the human mind, a man aspired to renown that had descended to theft. Yet in this dreadful complication of guilt and frenzy, there was room for compassion. The unfortunate wretch was sensible of the predominance of his black temperament; and the very morning of the assassination, asked for a surgeon to let him blood; and to the last gasp of being, he persisted that he should not have committed this crime, if he had been blooded. What the miserable man suffered is not to be described. When first raised and carried into the guard-chamber, the Garde-desceaux and the Duc d'Ayen ordered the tongs to be heated, and pieces torn from his legs, to make him declare his accomplices. The industrious art used to preserve his life was not less than there finement of torture by which they meant to take it away. The inventions to form the bed on which he lay (as the wounds on his leg prevented his standing), that his health might in no shape be affected, equalled what a reproving tyrant would have sought to indulge his own luxury. When carried to the dungeon, Damiens was wrapped up in mattresses, lest despair might tempt him to dash his brains out, but his madness was no longer precipitate. He even amused himself by indicating a variety of innocent persons as his accomplices; and sometimes, more harmlessly, by playing the fool with his judges. In no instance he sank either under terror or anguish. The very morning on which he was to endure the question, when told of it, ho said with the coolest intrepidity, ' La journee sera rude' -after it, insisted on some wine with his water, saying, 'I'l faut ici de la force.' And at the accomplishment of his tragedy, studied and prolonged on the precedent of Ravaillac's, he supported all with unrelaxed firmness; and even unremitted torture of four hours, which succeeded to his being two hours and a-half under the question, forced from him but some momentary yells.' -Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Second, ii., 281. That, in France, so lately as 1757, such a criminal should have been publicly torn to pieces by horses, that many persons of rank should have been present on the occasion, and that the sufferer allowed 'quelques plaisanteries' to escape him during the process, altogether leave us in a strange state of feeling regarding the affair of Damiens. TWELVE-DAY EVETwelfth-day Eve is a rustic festival in England. Persons engaged in rural employments are, or have heretofore been accustomed to celebrate it; and the purpose appears to be to secure a blessing for the fruits of the earth. In Herefordshire, at the approach of the evening, the farmers with their friends and servants meet together, and about six o'clock walk out to a field where wheat is growing. In the highest part of the ground, twelve small fires, and one large one, are lighted up. The attendants, headed by the master of the family, pledge the company when in old cider, which circulates freely on these occasions. A circle is formed round the large fire, when a general shout and hallooing takes place, which you hear answered from all the adjacent villages and fields. Sometimes fifty or sixty of these fires may be all seen at once. This being finished, the company return home, where the good housewife and her maids are preparing a good supper. A large cake is always provided, with a hole in the middle. After supper, the company all attend the bailiff (or head of the oxen) to the wain-house, where the following particulars are observed: The master, at the head of his friends, fills the cup (generally of strong ale), and stands opposite the first or finest of the oxen. He then pledges him in a curious toast: the company follow his example, with all the other oxen, and addressing each by his name. This being finished, the large cake is produced, and, with much ceremony, put on the horn of the first ox, through the hole above mentioned. The ox is then tickled, to make him toss his head: if he throw the cake behind, then it is the mistress's perquisite; if before (in what is termed the boosy), the bailiff himself claims the prize. The company then return to the house, the doors of which they find locked, nor will they be opened till some joyous songs are sung. On their gaining admittance, a scene of mirth and jollity ensues, which lasts the greatest part of the night.' - Gentleman's Magazine, February, 1791. The custom is called in Herefordshire Wassailing. The fires are de-signed to represent the Saviour and his apostles, and it was customary as to one of them, held as representing Judas Iscariot, to allow it to burn a while, and then put it out and kick about the materials. At Pauntley, in Gloucestershire, the custom has in view the prevention of the smut in wheat. 'All the servants of every farmer assemble in one of the fields that has been sown with wheat. At the end of twelve lands, they make twelve fires in a row with straw; around one of which, made larger than the rest, they drink a cheerful glass of cider to their master's health, and success to the future harvest; then returning home, they feast on cakes made with carraways, soaked in cider, which they claim as a reward for their past labour in sowing the grain.' 'In the south hams [villages] of Devonshire, on the eve of the Epiphany, the farmer, attended by his workmen, with a large pitcher of cider, goes to the orchard, and there encircling one of the best bearing trees, they drink the following toast three several times: Here's to thee, old apple-tree, Whence thou mayst bud, and whence thou mayst blow! And whence thou mayst bear apples enow! Hats full! caps full! Bushel-bushel-sacks full, And my pockets full too! Huzza! This done, they return to the house, the doors of which they are sure to find bolted by the females, who, be the weather what it may, are inexorable to all entreaties to open them till some one has guessed at what is on the spit, which is generally some nice little thing, difficult to be hit on, and is the reward of him who first names it. The doors are then thrown open, and the lucky clod-pole receives the tit-bit as his recompense. Some are so superstitious as to believe, that if they neglect this custom, the trees will bear no apples that year.' - Gentleman's Magazine, 1791, p. 403. OLD ENGLISH PRONUNCIATIONSThe history of the pronunciation of the English language has been little traced. It fully appears that many words have sustained a considerable change of pronunciation during the last four hundred years: it is more particularly marked in the vowel sounds. In the days of Elizabeth, high personages pronounced certain words in the same way as the common people now do in Scotland. For example, the wise Lord Treasurer Burleigh said whan instead of when, and war instead of were; witness a sentence of his own: 'At Enfield, fyndying a dozen in a plump, whan there was no rayne, I bethought myself that they war appointed as watchmen, for the apprehendyng of such as are missyng,' &c.-Letter to Sir Francis Walsingham, 1586. (Collier's Papers to Shakespeare Society.) Sir Thomas Gresham, writing to his patron in behalf of his wife, says: 'I humbly beseech your honour to be a stey and some comfort to her in this my absence.' Finding these men using such forms, we may allowably suppose that much also of their colloquial discourse was of the same homely character. Lady More, widow of the Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas More, writing to the Secretary Cromwell in 1535, beseeched his 'especial gude maistership, out of his 'abundant gudeness' to consider her case. 'So, bretherne, here is my maister,' occurs in Bishop Lacy's Exeter Pontifical about 1450. These pronunciations are the broad Scotch of the present day. Tway for two, is another old English pronunciation. 'By whom came the inheritance of the lordship of Burleigh, and other lands, to the value of twai hundred pounds yearly,' says a contemporary life of the illustrious Lord Treasurer. Tway also occurs in Piers Ploughman's Creed in the latter part of the fourteenth century: Thereon lay a litel chylde lapped in cloutes, And tweyne of tweie yeres olde,' &c. So also an old manuscript poem preserved at Cambridge: Dame, he seyde, how schalle we deo, He fayleth twaye tethe also. This is the pronunciation of Tweeddale at the present day; while in most parts of Scotland they say twa. Tway is nearer to the German zwei. A Scotsman, or a North of England man, speaking in his vernacular, never says 'all: 'he says 'a'.' In the old English poem of Havelok, the same form is used: He shall haven in his hand A Denemark and Engeland. The Scotsman uses onyx for any: Aye keep something to yoursel' Ye scarcely tell to ony. This is old English, as witness Caxton the printer in one of his publishing advertisements issued about 1490: 'If it pies ony man, spirituel or temporel,' &c. An Englishman in those days would say ane for one, even in a prayer: Thus was Thou aye, and evere salle be, Thre yn ane, and ane yn thre. A couplet, by the way, which gives another Scotch form in sal for shall. He also used among for among, sang for song, faught for fought, ('They faught with Heraud everilk ane.' Guy of Warwick.) tald for told, fund for found, Bane for gone, and awn for own. The last four occur in the curious verse inscriptions on the frescoes representing scenes in St. Augustine's life in Carlisle Cathedral, and in many other places, as a reference to Halliwell's Dictionary of Archaisms will shew. In a manuscript form of the making of an abbess, of probably the fifteenth century, mainteyne for maintain, sete for seat, and guere for quire, shew the prevalence at that time in England of pronunciations still retained in Scotland. (Dugdale's Monasticon, i. 437.) Abstain for abstain, persevered down to the time of Elizabeth: 'He that will doo this worke shall absteine from lecherousness and dronkennesse,' &e. Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft, 1584, where contein also occurs. The form cook for suck, which still prevails in Scotland, occurs in Capgrave's metrical Life of St. Katherine, about 1450. Ah! Jesa Christ, crown of maidens all, A maid bare thee, a maid gave thee wok. Stree for straw-being very nearly the Scottish pronunciation-occurs in Sir John Mandeville's Travels, of the fourteenth century. Even that peculiarly vicious northern form of shooter for suitor would appear, from a punning passage in Shakespeare, to have formerly prevailed in the south also: Boyct.-Who is the suitor? Rosatine.-Well, then, I am the shooter. It is to be observed of Shakespeare that he uses fewer old or northern words than some of his contemporaries; yet the remark is often made by Scotsmen, that much of his language, which the commentators explain for English readers, is to them intelligible as their vernacular, so that they are in a condition more readily to appreciate the works of the bard of Avon than even his own countrymen. The same remark may be made regarding Spenser, and especially with respect to his curious poem of' the Shepherd's Calendar. When he there tells of a ewe, that 'She mought ne gang on the greene,' he uses almost exactly the language that would be employed by a Selkirkshire shepherd, on a like occasion, at thepresent day. So also when Thenot says: 'Tell me, good Hobbinol, what gars thee greete ? ' he speaks pure Scotch. In this poem, Spenser also uses tinny for two, gait for goat, mickle for much, wark for work, wae for woe, ken for know, craig for the neck, warr for worse, hame for home, and teen for sorrow, all of these being Scottish terms. From that rich well of old English, Wycliffe's translation of the Bible, we learn that in the fourteenth century aboon, stood for above ('Gird abowen with knychtis gyrdill,' 2 Kings iii. 21), nowther was neither, and breed was bread ('Give to us this day oure breed,' &c.), all of these being Scottish pronunciations of the present day. Wycliffe also uses many words, now obsolete in England, but still used in Scotland, as oker for interest, orison for oration, almery, a press or cupboard, sad for firm or solid, tolbooth, a place to receive taxes ('He seith a man syttynge in a tolbothe, Matheu by name,' Malt. ix. 9); loan for a farm ('The first saide, Y have boucht a toun, and Y have node to go out and se it,' Luke xiv. 19), scarry for precipitous, repo for a handful of corn-straw ('Here's a rip to thy auld baggie.'-Burns. 'Whanne thou repest corn in the feeld, and forgetist and leeuest a rope, thou schalt not turn agen to take it,' Deut. xxiv. 19), forleit for left altogether. The last, a term which every boy in Scotland applies to the forsaking of a nest by the bird, was used on a remarkable public occasion to describe the act of James II. in leaving his country. 'Others,' says Sir George Mackenzie, 'were for declaring that the king had forleited the kingdom.' The differences of pronunciation which now exist between the current English and cognate languages chiefly lie in the vowel sounds. The English have flattened down the broad A in a vast number of cases, and played a curious legerdemain with E and I, while other nations have in these particulars made no change. It seems to have been a process of refinement, or what was thought to be such, in accordance with the advancing conditions of domestic life in a country on the whole singularly fortunate in all the circumstances that favour civilization. Whether there is a real improvement in the case may be doubted; that it is a deterioration would scarcely be asserted in any quarter. Even those, however, who take the most favourable view of it, must regret that the change should have extended to the pronunciation of Greek and Latin. To introduce the flat A for the broad one, and interchange the sounds of E and I, in these ancient languages, must be pronounced as an utterly unwarrantable interference with something not our own to deal with-it is like one author making alterations in the writings of another, an act which justice and good taste alike condemn. |