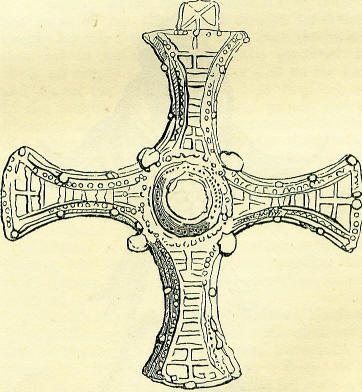

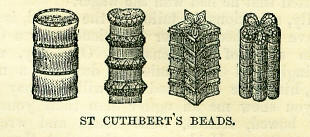

4th SeptemberBorn: Pindar, lyric poet, 518 B.C., Thebes; Alexander III of Scotland, 1241, Roxburgh; Gian Galeazzo Visconti, celebrated Duke of Milan, founder of the cathedral, 1402; Francois Réné, Vicomte de Chateaubriand, moral and romantic writer, 1768, St. Mato. Died: John Corvinus Huniades, Hungarian general, 1456, Zenalin; Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, favourite of Queen Elizabeth, 1588; John James Heidegger, Master of the Revels to George II; Charles Townshend, orator and statesman, 1767. Feast Day: Saints Marcellus and Valerian, martyrs, 179. St. Ultan, first bishop of Ardbraccan, in Meath, 656. St. Ida, widow, 9th century. The Translation of St. Cuthbert, about 995. St. Rosalia, virgin, 1160. St. Rosa of Viterbo, virgin, about 1252. TRANSLATION OF St. CUTHBERTCuthbert-originally a shepherd-boy in Lauderdale, afterwards a monk at Old Melrose on the Tweed, finally bishop of the Northumbrian island of Lindisfarne, in which capacity he died in the year 688-is remarkable for the thousand-years' long history which he had, after experiencing that which brings most men their quietus. Fearing future incursions of the Danes, he charged his little religious community that, in case any such event should take place, they would quit the island, taking his bones along with them. Eleven years after his death, having raised his body to give it a more honourable place, they were amazed to find it had undergone not the slightest decay. In consequence of this miraculous circumstance, it became, in its new shrine, an object of great popular veneration, and the cause of many other miracles; and so it continued till the year 875, when at length, to escape the Danes, the monks had to carry it away, and commence a wandering life on the mainland. After seven years of constant movement, the body of St. Cuthbert found rest at Chester-le-Street; but it was, in a sense, only temporary, for in 995, a new incursion of the Danes sent it off once more upon its travels. It was kept some time at Rippon, in Yorkshire, and when the danger was past, the monks set out on their return to Chester-le-Street. They were miraculously arrested, however, at a spot called Duirholm (the deer's meadow), on the river Wear, and there finally settled with the precious corpse of their holy patron, giving rise to what has since been one of the grandest religious establishments of the British empire, the cathedral of Durham. This is the event which was for some ages celebrated as the Translation of St. Cuthbert. For upwards of a hundred years, the tomb of St. Cuthbert, with his uncorrupted body, continued to be visited by devout pilgrims, and in 1104, on the erection of the present cathedral of Durham, it was determined to remove his remains to a shrine within the new structure. Some doubts had been expressed as to the permanence of his incorruptibility, and to silence all such misgivings, the clergy of the church, having met in conclave beside the saint's coffin the night before its intended removal, resolved to satisfy themselves by an actual inspection. After preparing themselves for the task by prayer, they removed, with trembling hands, the external fastenings, and opened the first coffin, within which a second was found, covered with rough hides, and enclosing a third coffin, enveloped in several folds of linen. On removing the lid of this last receptacle, a second lid appeared, which on being raised with much fear and agitation, the swathed body of the saint lay before them 'in a perfect state.' According to the narrative, the monks were appalled as if by some fearful interposition of Heaven; but after a short interval, they all fell flat on the ground, repeated amid a deluge of tears the seven penitential psalms, and prayed the Lord not to correct them in his anger, nor chasten them in his displeasure. The next day the miraculous body was shewn to the multitude, though it is honestly stated by the chronicler that the whole of it, including the face, was covered with linen, the only flesh visible being through a chink left in the cerecloths at the neck. Thereafter it was placed in the shrine destined for it behind the great altar, where it remained undisturbed for the ensuing four hundred and twenty-six years, and proved the source of immense revenues to the cathedral. No shrine in England was more lavishly adorned or maintained than that of St. Cuthbert; it literally blazed with ornaments of gold, silver, and precious stones, and to enrich the possessions of the holy man, and his representative the bishop of Durham, many a fair estate was impoverished or diverted from the natural heirs. The corporax cloth, which the saint had used to cover the chalice when he said mass, was enclosed in a silk banner, and employed in gaining victories for the Plantagenet kings of England. It turned the fate of the day at the battle of Neville's Cross, in 1346, when David of Scotland was defeated; and it soon after witnessed the taking of Berwick by Edward III. But all the glories of St. Cuthbert were to be extinguished at the Reformation, when his tomb was irreverently disturbed. It had, however, a better fate than many other holy places at this eventful epoch, as the coffin, instead of being ignominiously broken up, and its contents dispersed, was carefully closed, a new exterior coffin added, and the whole buried underneath the defaced shrine. For the greater part of three centuries more, the body of St. Cuthbert lay here undisturbed. He was not forgotten during this time, but a legend prevailed that the site of his tomb was known only to the Catholic clergy, three of whom, it was alleged, and no more, were intrusted with the secret at a time, one being admitted to a knowledge of it as another died-all this being in the hope of a time arriving when the shrine might be re-erected, and the incorrupt body presented once more to the veneration of the people. It is hardly necessary to observe, that this story of a secret was pure fiction, as the exact site of the tomb could be easily ascertained.  The next appearance of St. Cuthbert was in May 1827, when, in presence of a distinguished assemblage, including the dignitaries of Durham Cathedral, his remains were again exhumed from their triple encasement of coffins. After the larger fragments of the lid, sides, and ends of the last coffin had been removed, there appeared below a dark substance of the length of a human body, which proved to be a skeleton, lying with its feet to the east, swathed apparently in one or more shrouds of linen or silk, through which there projected the brow of the skull and the lower part of the leg bones. On the breast lay a small golden cross, of which a representation is here given. The whole body was perfectly dry, and no offensive smell was perceptible. From all the appearances, it was plain that the swathings had been wrapped round a dry skeleton, and not round a complete body, for not only was there no space left between the swathing and the bones, but not the least trace of the decomposition of flesh was to be found. It was thus clear that a fraud had been practised, and a skeleton dressed up in the habiliments of the grave, for the purpose of imposing on popular credulity, and benefiting thereby the influence and temporal interests of the church. In charity, however, to the monks of Durham, it may be surmised that the perpetration of the fraud was originally the work of a few, but having been successful in the first instance, the belief in the incorruptibility of St. Cuthbert's body came soon to be universally acquiesced in, by clergy as well as laity. Perhaps the history of the saint is not yet finished, and after the lapse of another cycle of years, a similar curiosity may lead to a re-examination of his relics, and Macaulay's New Zealander, after sketching the ruins of St. Paul's from a broken arch of London Bridge, may travel northwards to Durham, to witness the disinterment from the battered and grass-grown precincts of its cathedral, of the bones of the Lauderdale shepherd of the seventh century. ST. CUTHBERT'S BEADS On a rock, by Lindisfarne, Saint Cuthbert sits, and toils to frame The sea-born beads that bear his name: Such tales had Whitby's fishers told, And said they might his shape behold, And hear his anvil sound; A deadened clang-a huge dim form, Seen but, and heard, when gathering storm, And night were closing round. There is a Northumbrian legend, to the effect that, on dark nights, when the sea was running high, and the winds roaring fitfully, the spirit of St. Cuthbert was heard on the recurring lulls forging beads for the faithful. He used to sit in the storm-mist, among the spray and sea-weeds, on a fragment of rock on the shore of the island of Lindisfarne, and solemnly hammer away, using another fragment of rock as his anvil. A remarkable circumstance connected with the legend is, that after a storm the shore was found strewed with the beads St. Cuthbert was said to have so forged. And a still more remarkable circumstance connected with the legend consists in the fact that, although St. Cuthbert is, now, neither seen nor heard at work, the shore is still found strewed with the beads after a storm. The objects which are called beads are, in fact, certain portions of the fossilised remains of animals, called crinoids, which once inhabited the deep in myriads. Whole specimens of a crinoid are rare, but several parts of it are common enough.  It consisted of a long stem supporting a cup or head; and out of the head grew five arms or branches. The stem and the branches were flexible, and waved to and fro in the waters; but the base was firmly attached to the sea-bottom. The flexibility of the stems and branches was gained by peculiar formation; they were made of a series of flat plates or ossicula, like thick wafers piled one above another, and all strung together by a cord of animal matter, which passed through the entire animal. These plates, in their fossilised form detached from one another, are the beads in question. The absence of the animal matter leaves a hole in the centre of each piece, through which they can be strung together, rosary-fashion. They vary in size; some are about the diameter of a pea, others of a sixpence. They are most frequently found in fragments of the stems, an inch or two long, each inch containing about a dozen joints or beads. Crinoids are classed by modern naturalists with the order echinodermata-that is to say, among the sea-stars and sea-urchins. The entrochal marble of Derbyshire, used for chimney-pieces and ornamental purposes, includes a vast quantity of the fragments of crinoids. Those found at Lindisfarne have been embedded in shale, out of which they have been washed by the sea, and cast ashore. A MASTER OF THE REVELSJohn James Heidegger, a native of Switzerland, after wandering, in various capacities, through the greater part of Europe, came to England early in the eighteenth century; and by his witty conversation and consummate address, soon gained the good graces of the gay and fashionable, who gave him the appellation of the Swiss Count. His first achievement was to bring out an opera (Thomyres), then a novel and not very popular kind of entertainment in England. By his excellent arrangements, and judicious improvements on all previous performances, Heidegger may be said to have established the opera in public favour. Becoming manager of the Opera House in the Haymarket, he acquired the favour of George II; and introducing the then novel amusement of masquerades, he was appointed master of the revels, and superintendent of masquerades and operas to the royal household. Heidegger now became the fashion; the first nobility in the land vied in bestowing their caresses upon him. From a favourite, he became an autocrat; no public or private festival, ball, assembly, or concert was considered complete, if not submitted to the superintendence of the Swiss adventurer. Installed by common consent as arbiter elegantiarum, Heidegger, for a long period, realised an income of £5000 per annum, which he freely squandered in a most luxurious style of life, and in the exercise of a most liberal charity. Though tall and well made, Heidegger was characterised by a surpassing ugliness of face. He had the good sense to joke on his own peculiar hardness of countenance, and one day laid a wager with the Earl of Chesterfield, that the latter could not produce, in all London, an uglier face than his own. The earl, after a strict search, found a woman in St. Giles's, whose features were, at first sight, thought to be as ill-favoured as those of the master of the revels; but when Heidegger put on the woman's head-dress, it was unanimously admitted that he had won the wager. Jolly, a fashionable tailor of the period, is said to have also been rather conspicuous by a Caravaggio style of countenance. One day, when pressingly and inconveniently dunning a noble duke, his Grace exclaimed: 'I will not pay you, till you shew me an uglier man than yourself.' Jolly bowed, retired, went home, and wrote a polite note to Heidegger, stating that the duke particularly wished to see him, at a certain hour, on the following morning. Heidegger duly attended; the duke denied having sent for him; but the mystery was unravelled by Jolly making his appearance. The duke then saw the joke, and with laughter acknowledging the condition he stipulated was fulfilled, paid the bill. As might be supposed, Heidegger was the constant butt of the satirists and caricaturists of his time. Hogarth introduces him into several of his works, and a well-known sketch of 'Heidegger in a Rage,' attributed to Hogarth, illustrates a remarkable practical joke played upon the master of the revels. The Duke of Montague gave a dinner at the 'Devil Tavern' to several of the nobility and gentry, who were all in the plot, and to which Heidegger was invited. As previously arranged, the bottle was passed round with such celerity, that the Swiss became helplessly intoxicated, and was removed to another room, and placed upon a bed, where he soon fell into a pro-found sleep. A modeller, who was in readiness, then took a mould of his face, from which a wax mask was made. An expert mimic and actor, resembling Heidegger in height and figure, was instructed in the part he had to perform, and a suit of clothes, exactly similar to that worn by the master of the revels on public occasions, being procured, everything was in readiness for the next masquerade. The eventful evening having arrived, George II, who was in the secret, being present, Heidegger, as soon as his majesty was seated, ordered the orchestra to play God Save the King; but his back was no sooner turned, than his counterfeit commanded the musicians to play Over the Water to Charlie. The mask, the dress, the imitation of voice and attitude, were so perfect, that no one suspected a trick, and all the astonished courtiers, not in the plot, were thrown into a state of stupid consternation. Heidegger hearing the change of music, ran to the music-gallery, stamped and raved at the musicians, accusing them of drunkenness, or of a design to ruin him, while the king and royal party laughed immoderately. While Heidegger stood in the gallery, God Save the King was played, but when he went among the dancers, to see if proper decorum were kept by the company, the counterfeit stepped forward, swore at the musicians, and asked: had he not just told them to play Over the Water to Charlie? A pause ensued, the musicians believing Heidegger to be either drunk or mad, but as the mimic continued his vociferations, Charlie was played again. The company was by this time in complete confusion. Several officers of the guards, who were present, believing a studied insult was intended to the king, and that worse was to follow, drew their swords, and cries of shame and treason resounded from all sides. Heidegger, in a violent rage, rushed towards the orchestra, but he was stayed by the Duke of Montague, who artfully whispered that the king was enraged, and his best plan was first to apologise to the monarch, and then discharge the drunken musicians. Heidegger went, accordingly, to the circle immediately before the king, and made a humble apology for the unaccountable insolence of the musicians; but he had scarcely spoken ere the counterfeit approaching, said in a plaintive voice: 'Indeed, sire, it is not my fault, but,' pointing to the real Heidegger, 'that devil in my likeness.' The master of the revels, turning round and seeing his counterpart, stared, staggered, turned pale, and nearly swooned from fright. The joke having gone far enough, the king ordered the counterfeit to unmask; and then Heidegger 's fear turning into rage, he retired to his private apartment, and seating himself in an arm-chair, ordered the lights to be extinguished, vowing he would never conduct another masquerade unless the surreptitiously-obtained mask were immediately broken in his presence. The mask was delivered up, and Hogarth's sketch represents Heidegger in his chair, attended by his porter, carpenter, and candle-snuffer, the obnoxious mask lying at his feet. Heidegger gave grand entertainments to his friends; the king even condescended to visit him in his house at Barn-Elms. One day, a discussion took place at his table as to which nation in Europe had the best-founded claim to ingenuity. After various opinions had been given, Heidegger claimed that character for the Swiss, appealing to himself as a case in point. 'I was,' said he, 'born a Swiss, in a country where, had I continued to tread in the steps of my simple but honest forefathers, twenty pounds a year would have been the utmost that art or industry could have procured me. With an empty purse, a solitary coat on my back, and almost two shirts, I arrived in England, and by the munificence of a generous prince, and the liberality of a wealthy nation, am now at the head of a table, covered with the delicacies of the season, and wines from different quarters of the globe; I am honoured with the company, and enjoy the approbation, of the first characters of the age, in rank, learning, arms, and arts, with an income of five thousand pounds a year. Now, I defy any Englishman or native of any other country in Europe, how highly soever he may be gifted, to go to Switzerland, and raise such a sum there, or even to spend it.' Although an epicure and a wine-bibber, Heidegger lived to the age of ninety years. He died on the 4th of September 1749, and was buried in the church of Richmond, in Surrey. With all his faults, it must not be forgotten that he gave away large sums in charity. And in spite of his proverbial ugliness - With a hundred deep wrinkles impressed on his front, Like a map with a great many rivers upon 't '- an engraving of his face, taken from a mask after death, and inserted in Lavater's Physiognomy, exhibits strong marks of a benevolent character, and features by no means displeasing or disagreeable. |