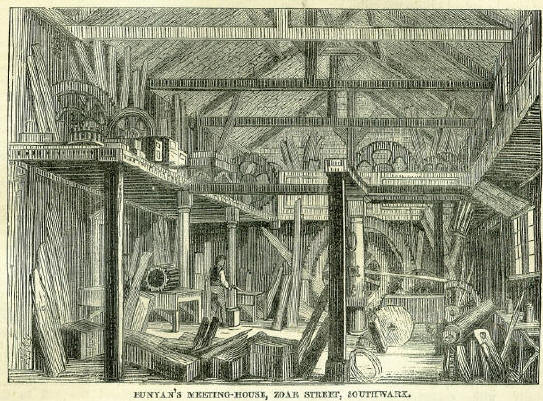

31st AugustBorn: Caius Cæsar Caligula, Roman emperor, 12 A. D., Antium. Died: Henry V, king of England, 1422, Vincennes, near Paris; Etienne Pasquier, French jurist and historian, 1615, Paris; John Bunyan, author of the Pilgrim's Progress, 1688, Snowhill, London; Dr. William Borlase, antiquary, 1772, Ludgran, Cornwall; F. A. Danican (Phillidor), noted for his skill in chess-playing, 1795; Dr. James Currie, biographer of Burns, 1805, Sidmouth;; Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth, 1817, Devonport. Feast Day: St. Aldan or Aedan, bishop of Lindisfarne, confessor, 651. St. Cuthburge, queen of Northumbria, virgin and abbess, beginning of 8th century. St. Raymund Nonnatus, confessor, 1240. St. Isabel, virgin, 1270. JOHN BUNYAN Everybody has heard of his birth at Elstow, about a mile from Bedford, in 1628; that he was bred a tinker; that his childhood was afflicted with remorse and dreams of fiends flying away with him; that, as he grew up, he 'danced, rang church-bells, played at tip-cat, and read Sir Bevis of Southampton,' for which he suffered many stings of conscience; that his indulgence in profanity was such, that a woman of loose character told him 'he was the ungodliest fellow for swearing she had ever heard in all her life,' and that 'he made her tremble to hear him;' that he entered the Parliamentary army, and served against the king in the decisive campaign of 1645; that, after terrible mental conflicts, he became converted, a Baptist, and a preacher; that at the Restoration in 1660 he was cast into Bedford jail, where, with intervals of precarious liberty, he remained for twelve years, refusing to be set at large on the condition of silence, with the brave answer: 'If you let me out today, I'll preach again tomorrow;' that, on his release, the fame of his writings, and his ability as a speaker, drew about him large audiences in London and elsewhere, and that, a few months before the Revolution of 1688, he caught a fever in consequence of a long ride from Reading in the rain, and died at the house of his friend, Mr. Strudwick, a grocer at the sign of the Star, on Snowhill, London. Bunyan was buried in Bunhill Fields, called by Southey, 'the Campo Santo of the Dissenters.' There sleep Dr. John Owen and Dr. Thomas Goodwin, Cromwell's preachers; George Fox, the Quaker; Daniel Defoe, Dr. Isaac Watts, Susannah Wesley, the mother of the Wesleys; Ritson, the antiquary; William Blake, the visionary poet and painter; Thomas Stothard, and a host of others of greater or lesser fame in their separate sects. A monument, with a recumbent statue of Bunyan, was erected over his grave in 1862. 'It is a significant fact,' observes Macaulay, 'that, till a recent period, all the numerous editions of the Pilgrim's Progress were evidently meant for the cottage and the servants' hall. The paper, the printing, the plates were of the meanest description. In general, when the educated minority differs [with the uneducated majority] about the merit of a book, the opinion of the educated minority finally prevails. The Pilgrim's Progress is perhaps the only book about which, after the lapse of a hundred years, the educated minority has come over to the opinion of the common people.' The literary history of the Pilgrim's Progress is indeed remarkable. It attained quick popularity. The first edition was 'Printed for Nath. Ponder, at the Peacock in the Poultry, 1678,' and before the year closed a second edition was called for. In the four following years it was reprinted six times. The eighth edition, which contains the last improvements made by the author, was published in 1682, the ninth in 1684, the tenth in 1685. In Scotland and the colonies, it was even more popular than in England. Bunyan tells that in New England his dream was the daily subject of conversation of thousands, and was thought worthy to appear in the most superb binding. It had numerous admirers, too, in Holland and among the Huguenots in France. Envy started the rumour that Bunyan did not, or could not have written the book, to which, with scorn to tell a lie,' he answered: It came from mine own heart, so to my head, And thence into my fingers trickled; Then to my pen, from whence immediately On paper I did dribble it daintily. Manner and matter too was all mine own, Nor was it unto any mortal known, Till I had done it. Nor did any then By books, by wits, by tongues, or hand, or pen, Add five words to it, or write half a line Thereof: the whole and every whit is mine. Yet the favour and enormous circulation of the Pilgrim's Progress was limited to those who read for religious edification and made no pretence to critical tastes. When the literati spoke of the book, it was usually with contempt. Swift observes in his Letter to a Young Divine: 'I have been better entertained and more informed by a few pages in the Pilgrim's Progress than by a long discourse upon the will and intellect, and simple and complex ideas;' but we apprehend the remark was designed rather to depreciate metaphysics than to exalt Bunyan. Young, of the Night Thoughts, coupled Bunyan's prose with D'Urfey's doggerel, and in the Spiritual Quixote the adventures of Christian are classed with those of Jack the Giant Killer and John Hickathrift. But the most curious evidence of the rank assigned to Bunyan in the eighteenth century appears in Cowper's couplet, written so late as 1782: I name thee not, lest so despised a name Should move a sneer at thy deserved fame. It was only with the growth of purer and more Catholic principles of criticism towards the close of the last century and the beginning of the present, that the popular verdict was affirmed and the Pilgrim's Progress registered among the choicest English classics. With almost every Christmas there now appears one or more editions of the Pilgrim, sumptuous in typography, paper, and binding, and illustrated by favourite artists. Ancient editions are sought for with eager rivalry by collectors; but, strange to say, only one perfect copy of the first edition of 1678 is known to be extant. Originally published for a shilling, it was bought, a few years ago, by Mr. H. S. Holford, of Tetbury, in its old sheep-skin cover, for twenty guineas. It is probable that, if offered again for sale, it would fetch twice or thrice that sum. A curious anecdote of Bunyan appeared in the Morning Advertiser a few years ago. To pass away the gloomy hours in prison, Bunyan took a rail out of the stool belonging to his cell, and, with his knife, fashioned it into a flute. The keeper, hearing music, followed the sound to Bunyan's cell; but, while they were unlocking the door, the ingenious prisoner replaced the rail in the stool, so that the searchers were unable to solve the mystery; nor, during the remainder of Bunyan's residence in the jail, did they ever discover how the music had been produced. In an old account of Bedford, there is an equally good anecdote, to the effect that a Quaker called upon Bunyan in jail one day, with what he professed to be a message from the Lord. 'After searching for thee,' said he, 'in half the jails of England, I am glad to have found thee at last.' 'If the Lord sent thee,' said Bunyan sarcastically, 'you would not have needed to take so much trouble to find me out, for He knows that I have been in Bedford jail these seven years past.' The portrait of Bunyan represents a robust man, with a large well-formed head, of massive but not unhandsome features, and a profusion of dark hair falling in curls upon his shoulders. The head is well carried, and the expression of the face open and manly -altogether a prepossessing, honest-looking man.  In an obscure part of the borough of Southwark -in Zoar Street, Gravel Lane-there is an old dissenting meeting-house, now used as a carpenter's shop, which tradition affirms to have been occupied by John Runyan for worship. It is known to havebeen erected a short while before the Revolution, by a few earnest Protestant Christians, as a means of counteracting a Catholic school which had been established in the neighbourhood under the auspices of James II. But Banyan may have once or twice or occasionally preached in it during the year preceding his death. From respect for the name of the illustrious Nonconformist, we have had a view taken of the interior of the chapel in its present state. PHILLIDOR, THE CHESS-PLAYERPhillidor is known, in the present day, not under his real name, but under one voluntarily assumed; and not for the studies to which he devoted most time and thought, but for a special and exceptional talent. Francois Andre Danican, born at Dreux, in France, in 1726, was in his youth one of the pages to Louis XIV, and was educated as a court-musician. He composed a motet for the Royal Chapel at the early age of fifteen. Having by some means lost the sunshine of regal favour, he earned a living chiefly by teaching music, filling up vacant time as a music-copyist for the theatres and concerts, and occasionally as a composer. He composed music to Dryden's Alexander's Feast; in 1754, he composed a Lauda Jerusalem for the chapel at Versailles; in 1759, an operetta called Blaise is Savetier; and then followed, in subsequent years, Le Mare'chal-ferrant, Le Sorcier, Ernelinde, Perse'e, Thémistocle'e, Alceste, and many other operas-the whole of which are now forgotten. Danican, or-to give the name by which he was generally known-Phillidor, lives in fame through his chess-playing, not his music. When quite a young man, an intense love of chess seized him; and at one time he entertained a hope of adding to his income by exhibiting his chess-playing powers, and giving instructions in the game. With this view he visited Holland, Germany, and England.. While in England, in 1749, he published. his Analyse des Echecs - a work which has taken its place among the classics of chess. During five or six years of residence in London, his remarkable play attracted much attention. Forty years passed over his head, marked by many vicissitudes as a chess-player as well as a composer, when the French Revolution drove him again to England, where he died on the 31st August 1795. The art of playing chess blind-fold was one by which Phillidor greatly astonished his contemporaries, though he was not the first to do it. Buzecca, in 1266, played three games at once, looking at one board, but not at the other two; all three of his competitors were skilful players; and his winning of two games, and drawing a third, naturally excited much astonishment. Ruy Lopez, Mangiolini, Terone, Medrano, Leonardi da Cutis, Paoli Boi, Salvio, and others who lived between the thirteenth and the seventeenth centuries, were also able to play at chess without seeing the board. Father Sacchieri, who was professor of mathematics at Pavia early in the last century, could play three games at once against three players, without seeing any of the boards. Many of these exploits were not well known until recently; and, on that account, Phillidor was regarded as a prodigy. While yet a youth, he used to play imaginary games of chess as he lay awake in bed. His first real game of this kind he won of a French abbe. He afterwards became so skilful in this special knack, that he could play nearly as well without as with seeing the board, even when playing two games at once. Forty years of wear and tear did not deprive him of this faculty; for when in England, in 1783, he competed blindfold against three of the best players then living, Count Bruhl, Baron Maseres, and Mr. Bowdler: winning two of the games and drawing the third. On another occasion he did the same thing, even giving the odds of 'the pawn and move' (as it is called) to one of his antagonists. What surprised the lookers-on most was, that Phillidor could keep up a lively conversation during these severe labours. Phillidor's achievement has been far outdone in recent years by Morphy, Paulsen, and Blackburne, in respect to the number of games played at once; but the lively Frenchman carried off the palm as a gossip and a player at the same time. SCOTCH NON-TRADING LEAGUE AGAINST ENGLANDOn this day, in 1527, is dated the 'ordinary' of the corporation of weavers in Newcastle, in which, amongst other regulations, there is a strict one that no member should take a Scotsman to apprentice, or set any of that nation to work, under a penalty of forty shillings. To call a brother, 'Scot' or 'mansworn,' inferred a forfeit of 6s. 8d., 'without any forgiveness.'-Brand's Hist. of Newcastle. The superior ability of the Scottish nation, in the competitions of life, seems to have made an unusual impression on their Newcastle neighbours. To be serious-we can fortunately show our freedom from national partiality by following up the above with an example of the like illiberality on the part of Scotland towards England. It consists of a sort of covenant entered into in the year 1752 by the drapers, mercers, milliners, &c., of Edinburgh, to cease dealing with commercial travellers from England-what were then called English Riders. 'Considering'-so runs the language of this document-'that the giving orders or commissions to English Riders (or clerks to English merchants), when they come to this city, tends greatly to the destruction of the wonted wholesale trade thereof, from which most of the towns in Scotland used to be furnished with goods, and that some of these English Riders not only enhances the said wholesale trade, but also corresponds with, and sells goods to private families and persons, at the same prices and rates as if to us in a wholesale way, and that their frequent journeys to this place are attended with high charges, which consequently must be laid on the cost of those goods we buy from them, and that we can be as well served in goods by a written commission by post (as little or no regard is had by them to the patterns or colours of goods which we order them to send when they are here), therefore, and for the promoting of trade, we hereby voluntarily bind and oblige ourselves that, in no time coming, we shall give any personal order or commission for any goods we deal in to any English dealer, clerk, or rider whatever who shall come to Scotland.' They add an obligation to have no dealings 'with any people in England who shall make a practice of coming themselves or sending clerks or riders into Scotland.' The penalty was to be two pounds two shillings for every breach of the obligations. This covenant was drawn out on a good sheet of vellum bearing a stamp, and which was to be duly registered, in order to give it validity at law against the obligants in case of infraction. It bears one hundred and fifty-four signatures, partly of men, generally in good and partly of women in bad holograph.' It is endorsed, 'Resolution and Agreement of the Merchants of Edinburgh for Discouraging English Riders from Coming into Scotland.' This strange covenant, as it appears to us, seems to have made some noise, for, several months after its date, the following paragraph regarding it appeared in an English newspaper: We hear from Scotland, that the trading people throughout that kingdom have agreed, by a general association, not to give any orders for the future to any English riders that may be sent among them by the English tradesmen. This resolution is owing to the unfair behaviour of the itinerants, whose constant practice it is to undermine and undersell each other, without procuring any benefit to the trading interest of the nation in general, by such behaviour; which, on the contrary, only tends to unsettle the course of business and destroy that connection and good understanding between people, who had better not deal together at all, than not do it with spirit and mutual confidence. It is said also that several towns in England have already copied this example.'-London Daily Advertiser, January 27, 1753. |