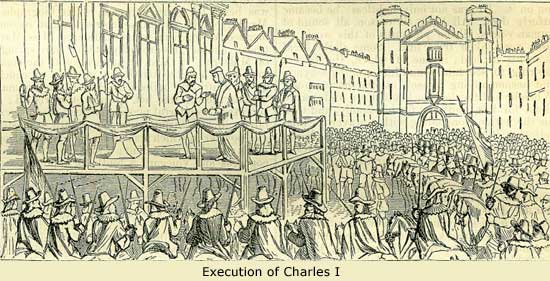

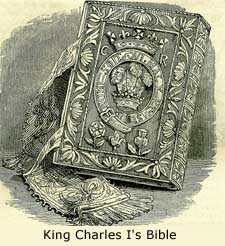

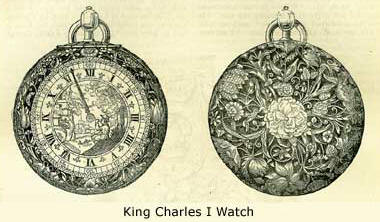

30th JanuaryBorn: Charles Rollin, 1661, Paris; Walter Savage Lander, 1775; Charles Lord Metcalfe, 1785. Died: William Chillingworth, 1644; King Charles I, 1649; Dr. John Robison, mechanical philosopher, 1805. Feast Day: St. Barsimaeus, bishop and martyr, 2nd century. St. Martina, virgin and martyr, 3rd century. St. Aldegondes, virgin and abbess, 660. St. Bathildes, queen of France, 680. LORD METCALFECharles Metcalfe-raised at the close of a long official life to the dignity of a peer of the realm-was a notable example of that kind of English-man, of whom Wellington was the type,-modest, steady, well-intending, faithful to his country and to his employers; in afford, the devotee of duty. A great part of his life was spent in India-some years were given to Jamaica-finally, he took the government of Canada. There, when enjoying at fifty-nine the announcement of his peerage, he was beset by a cruel disease. His biographer Mr. Kaye tells one correspondent recommended Mesmerism, which had cured Miss Martineau; another, Hydropathy, at the 'pure springs of Malvern;' a third, an application of the common dock-leaf; a fourth, an infusion of couch grass; a fifth, the baths of Docherte, near Vienna; a sixth, the volcanic hot springs of Karlsbad; a seventh, a wonderful plaster, made of rose-leaves, olive oil, and turnip juice; an eighth, a plaster and powder in which some part of a young frog was a principal ingredient; a ninth, a mixture of copperas and vinegar; a tenth, an application of pure ox-gall; an eleventh, a mixture of Florence oil and red precipitate; whilst a twelfth was certain of the good effects of Homoeopathy, which had cured the well-known 'Charlotte Elizabeth.' Besides these varied remedies, many men and women, with infallible recipes or certain modes of treatment, were recommended to him by themselves and others. Learned Italian professors, mysterious American women, erudite Germans, and obscure Irish quacks-all had cured cancers of twenty years' standing, and all were pressing, or pressed forward, to operate on Lord Metcalfe.' The epitaph written upon Lord Metcalfe by Lord Macaulay gives his worthy career and some-thing of his character in words that could not be surpassed: 'Near this stone is laid Charles Theophilus, first and last Lord Metcalfe, a statesman tried in many high posts and difficult conjunctures, and found equal to all. The three greatest dependencies of the British crown were successively entrusted to his care. In India his fortitude, his wisdom, his probity, and his moderation are held in honourable remembrance by men of many races, languages, and religions. In Jamaica, still convulsed by a social revolution, he calmed the evil passions which long-suffering had engendered in one class, and long domination in another. In Canada, not yet recovered from the calamities of civil war, he reconciled contending factions to each other and to the mother country. Public esteem was the just reward of his public virtue; but those only who enjoyed the privilege of his friendship could appreciate the whole worth of his gentle and noble nature. Costly monuments in Asiatic and American cities attest the gratitude of nations which he ruled; this tablet records the sorrow and the pride with which his memory is cherished by private affection. He was born the 30th day of January 1785. He died the 5th day of September 1816.' EXECUTION OF CHARLES IThough the anniversary of the execution of Charles I is very justly no longer celebrated with religious ceremonies in England, one can scarcely on any occasion allow the day to pass without a feeling of pathetic interest in the subject. The meek behaviour of the King in his latter days, his tender interviews with his little children when parting with them for ever, the insults he bore so well, his calmness at the last on the scaffold, combine to make us think leniently of his arbitrary rule, his high-handed proceedings with Nonconformists, and even his falseness towards the various opposing parties he had to deal with. When we further take into account the piety of his meditations as exhibited in the Eikon Basilike, we can scarcely wonder that a very large proportion of the people of England, of his own generation, regarded him as a kind of martyr, and cherished his memory with the most affectionate regard. Of the highly inexpedient nature of the action, it is of no use to speak, as its consequences in causing retaliation and creating a reaction for arbitrary rule, are only too notorious. Charles was put to death upon a scaffold raised in front of the Banqueting House, Whitehall. There is reason to believe that he was conducted to this sad stage through a window, from which the frame had been taken out, at the north extremity of the building near the gate. It was not so much elevated above the street, but that he could hear people weeping and praying for him below. A view of the dismal scene was taken at the time, engraved, and published in Holland, and of this a transcript is here presented.  The scaffold, as is well known, was graced that day by two executioners in masks; and as to the one who used the axe a question has arisen, who was he? The public seems to have been kept in ignorance on this point at the time; had it been otherwise, he could not have long escaped the daggers of the royalists. Immediately after the Restoration, the Government made an effort to discover the masked headsman; but we do not learn that they ever succeeded. ' William Lilly, the famous astrologer, having dropped a hint that he knew something on the subject, was examined before a parliamentary committee at that time, and gave the following information: 'The next Sunday but one after Charles the First was beheaded, Robert Spavin, Secretary unto Lieutenant-General Cromwell, invited himself to dine with me, and brought Anthony Peirson and several others along with him to dinner. Their principal discourse all dinner-time was only, who it was that beheaded the King. One said it was the common hangman; another, Hugh Peters; others were nominated, but none concluded. Robert Spavin, so soon as dinner was done, took me to the south window. Saith he, 'These are all mistaken; they have not named the man that did the fact: it was Lieutenant-Colonel Joyce. I was in the room when he fitted himself for the work-stood behind him when he did it-when done went in again with him. There's no man knows this but my master (viz. Cromwell), Commissary Ireton, and myself.' 'Both not Mr. Rushworth know it?' said I. 'No, he doth not,' saith Spavin. The same thing Spavin since had often related to me when we were alone. Mr. Prynne did, with much civility, make a report hereof in the house.' Nevertheless, the probability is that the King's head was in reality cut off by the ordinary executioner, Richard Brandon. When, after the Restoration, an attempt was made to fix the guilt on one William Hulett, the following evidence was given in his defence, and there is much reason to believe that it states the truth. 'When my Lord Capell, Duke Hamilton, and the Earl of Holland, were beheaded in the Palace Yard, Westminster [soon after the King], my Lord Capell asked the common hangman, 'Did you cut off my master's head? ' 'Yes,' saith he. 'Where is the instrument that did it?' He then brought the axe. 'Is this the same axe? are you sure?' said my lord. 'Yes, my lord,' saith the hangman; 'I am very sure it is the same.' My Lord Capell took the axe and kissed it, and gave him five pieces of gold. I heard him say, 'Sirrah, Wert thou not afraid?' Saith the hangman, 'They made me cut it off, and I had thirty pounds for my pains.''  We have engraved two of the relics associated with this solemn event in our history. First is the Bible believed to have been used by Charles, just previous to his death, and which the King is said to have presented to Bishop Juxon, though this circumstance is not mentioned in any contemporaneous account of the execution. The only notice of such a volume, as a dying gift, appears to be that recorded by Sir Thomas Herbert, in his narrative, which forms a part of The Memoirs of the last Two Years of the Reign of that unparalleled Prince, of ever-blessed memory, King Charles I; London, 1702, p. 129, in the following passage: 'The King thereupon gave him his hand to kiss, having the day before been graciously pleased, under his royal hand, to give him a certificate, that the said Mr. Herbert was not imposed upon him, but by his Majesty made choice of to attend him in his bedchamber, and had served him with faithfulness and loyal affection. His Majesty also delivered him his Bible, in the margin whereof he had, with his own hand, written many annotations and quotations, and charged him to give it to the Prince so soon as he returned.' That this might be the book above represented is rendered extremely probable, on the assumption that the King would be naturally anxious that his son should possess that very copy of the Scriptures which had been provided for himself when he was Prince of Wales. ' It will be observed that the cover of the Bible is decorated with the badge of the Principality within the Garter, surmounted by a royal coronet (in silver gilt), enclosed by an embroidered border; the initial P. being apparently altered to an R., and the badges of the Rose and Thistle upon a ground of blue velvet: the book was, therefore, bound between the death of Prince Henry, in 1612, and the accession of Charles to the throne in 1625, when such a coronet would be no longer used by him. If the Bible here represented be that referred to by Herbert, the circumstance of Bishop Juxon becoming the possessor of it might be accounted for by supposing that it was placed in his hands to be transmitted to Charles II, with the George of the Order of the Garter belonging to the late King, well known to have been given to that prelate upon the scaffold. The Bible was, when Mr. Roach Smith wrote the above details in his Collectanea Antiqua, in the possession of James Skene, Esq, of Rubislaw.  Next is engraved the silver clock-watch, which had long been used by King Charles, and was given by him to Sir Thomas Herbert, on the morning of his execution. The face is beautifully engraved; and the back and rim are elaborately chased, and pierced with foliage and scroll-work. It has descended as an heirloom to William Townley Mitford, Esq.; and from its undoubted genuineness must be considered as one of the most interesting relics of the monarch. The body of the unfortunate King was embalmed immediately after the execution, and taken to Windsor to be interred. A smallgroup of his friends, including his relative the Duke of Richmond, was permitted by Parliament to conduct a funeral which should not cost above five hundred pounds. Disdaining an ordinary grave, which had been dug for the King in the floor of the chapel, they found a vault in the centre of the quire, containing two coffins, believed to be those of Henry VIII and his queen Jane Seymour; and there his coffin was placed, with no ceremony beyond the tears of the mourners, the Funeral Service being then under prohibition. The words 'King Charles, 1648,' inscribed on the outside of the outer wooden coffin, alone marked the remains of the unfortunate monarch. These sad rites were paid at three in the afternoon of the 19th of February, three weeks after the execution. The coffin of King Charles was seen in the reign of William III, on the vault being opened to receive one of the Princess Anne's children. It remained unobserved, forgotten, and a matter of doubt for upwards of a century thereafter, till, in 1813, the vault had once more to be opened for the funeral of the Duchess of Brunswick. On the 1st of April, the day after the interment of that princess, the Prince Regent, the Duke of Cumberland, the Dean of Windsor, Sir Harry Halford, and two other gentlemen assembled at the vault, while a search was made for the remains of King Charles. The leaden coffin, with the inscription, was soon found, and partially opened, when the body of the decapitated king was found tolerably entire and in good condition, amidst the gums and resins which had been employed in preserving it. 'At length the whole face was disengaged from its covering. The complexion of the skin of it was dark and discoloured. The forehead and temples had lost little or nothing of their muscular substance; the cartilage of the nose was gone; but the left eye, in the first moment of exposure, was open and full, though it vanished almost immediately; and the pointed beard, so characteristic of the reign of King Charles, was perfect. The shape of the face was a long oval; many of the teeth remained. When the head had been entirely disengaged from the attachments which confined it, it was found to be loose, and without any difficulty was taken up and held to view. The back part of the scalp was perfect, and had a remarkably fresh appearance; the pores of the skin being more distinct, as they usually are when soaked in moisture; and the tendons and filaments of the neck were of considerable substance and firmness. The hair was thick at the back part of the head, and, in appearance, nearly black. On holding up the head to examine the place of separation from the body, the muscles of the neck had evidently retracted themselves considerably; and the fourth cervical vertebra was found to be cut through its substance, transversely, leaving the surfaces of the divided portions perfectly smooth and even.' The first Lord Holland used to relate, with some pleasantry, a usage of his father, Sir Stephen Fox, which proves the superstitious veneration in which the Tories held the memory of Charles I. During the whole of the 30th of January, the wainscot of the house used to be hung with black, and no meal of any sort was allowed till after midnight. This attempt at rendering the day melancholy by fasting had a directly contrary effect on the children; for the housekeeper, apprehensive that they might suffer from so long an abstinence from food, used to give the little folks clandestinely as many comfits and sweet-meats as they could eat, and Sir Stephen's intended feast was looked to by the younger part of the family as a holiday and diversion.-Correspondence of C. J. Fox, edited by Earl Russell. There is a story told regarding a Miss Russell, great-grand-daughter of Oliver Cromwell, who was waiting-woman to the Princess Amelia, daughter of George II, to the effect that, while engaged in her duty one 30th of January, the Prince of Wales came into the room, and sportively said: 'For shame, Miss Russell! why have you not been at church, humbling yourself with weepings and wailings for the sins on this day committed by your ancestor?' To which Miss Russell answered: 'Sir, for a descendant of the great Oliver Cromwell, it is humiliation sufficient to be employed, as I am, in pinning up the tail of your sister!'-Rede's Anecdotes, 1799. THE CALVES'-HEAD CLUBThe Gentleman's Magazine for 1735, vol. v., p. 105, under the date of January 30th, gives the following piece of intelligence: 'Some young noblemen and gentlemen met at a tavern in Suffolk Street [Charing Cross], called themselves the Calves'-Head Club, dressed up a calf's head in a napkin, and after some huzzas threw it into a bonfire, and dipped napkins in their red wine and waved them out at window. The mob had strong beer given them, and for a time hallooed as well as the best, but taking disgust at some healths proposed, grew so outrageous that they broke all the windows, and forced them-selves into the house; but the guards being sent for, prevented further mischief.' The Weekly Chronicle, of February 1, 1735, states that the damage was estimated at 'some hundred pounds,' and that 'the guards were posted all night in the street, for the security of the neighbourhood.' Horace Walpole says the mob destroyed part of the house. Sir William (called Hellfire) Stanhope was one of the members. This riotous occurrence was the occasion of some verses in The Grub Street Journal, of which the following lines may be quoted as throwing some additional light on the scene: Strange times! when noble peers, secure from riot, Can't keep Noll's annual festival in quiet, Through sashes broke, dirt, stones, and brands thrown at 'em, Which, if not stand- was brand- alum magnatum. Forced to run down to vaults for safer quarters, And in coal-holes their ribbons hide and garters. The manner in which Noll's (Oliver Cromwell's) 'annual festival' is here alluded to, seems to shew that the bonfire, with the calf's-head and other accompaniments, had been exhibited in previous years. In confirmation of this fact, there exists a print entitled The True Effigies of the Members of the Calves'-Head Club, held on the 30th of January 1734, in Suffolk Street, in the County of Middlesex; being the year before the riotous occurrence above related. This print, as will be observed in the copy above given, skews a bonfire in the centre of the foreground, with the mob; in the background, a house with three windows, the central window exhibiting two men, one of whom is about to throw the calf's-head into the bonfire below. The window on the right shews three persons drinking healths, that on the left two other persons, one of whom wears a mask, and has an axe in his hand. It is a singular fact that a political club of this revolutionary character should have been in existence at so late a period as the eighth year of the reign of George II. We find no mention of it for many years preceding this time, and after the riot it was probably broken up. The first notice that we find of this strange club is in a small quarto tract of twenty-two pages, which has been reprinted in the Harleian Miscellany. It is entitled The Secret History of the Calves-Head Club; or, the Republican unmask'd. Wherein is fully shewn the Religion of the Calves-Head Heroes, in their Anniversary Thanksgiving Songs on the 30th of January, by them called Anthems, for the Years 1693, 1694, 1695, 1696, 1697. Now published to demonstrate the restless implacable Spirit of a certain Party still amongst us, who are never to be satisfied until the present Establishment in Church and State is subverted. The Second Edition. London, 1703. The Secret History, which occupies less than half of the twenty-two pages, is vague and unsatisfactory, and the five songs or anthems are entirely devoid of literary or any other merit. As Queen Anne commenced her reign in March 1702, and the second edition of this tract is dated 1703, it may be presumed that the first edition was published at the beginning of the Queen's reign. The author states, that: 'after the Restoration the eyes of the Government being upon the whole party, they were obliged to meet with a great deal of precaution, but now they meet almost in a public manner, and apprehend nothing.' Yet all the evidence which he produces concerning their meetings is hearsay. He had never himself been present at the club. He states, that 'happening in the late reign to be in company of a certain active Whig,' the said Whig informed him that he knew most of the members of the club, and had been often invited to their meetings, but had never attended: 'that Milton and other creatures of the Commonwealth had instituted this club (as he was informed) in opposition to Bishop Juxon, Dr. Sanderson, Dr. Hammond, and other divines of the Church of England, who met privately every 30th of January, and though it was under the time of the usurpation had compiled a private form of service of the day, not much. different from what we now find in the Liturgy.' From this statement it appears that the author's friend, though a Whig, had no personal knowledge of the club. The slanderous rumour about Milton may be passed over as unworthy of notice, this untrustworthy tract being the only authority for it. But the author of the Secret History has more evidence to produce. 'By another gentleman, who, about eight years ago, went, out of mere curiosity, to their club, and has since furnished me with the following papers [the songs or anthems], I was informed that it was kept in no fixed house, but that they removed as they saw convenient; that the place they met in when he was with them was in a blind alley about Moor-fields; that the company wholly consisted of Independents and Anabaptists (I am glad, for the honour of the Presbyterians, to set down this remark); that the famous Jerry White, formerly chaplain to Oliver Cromwell (who, no doubt of it, came to sanctify with his pious exhortations the ribaldry of the day), said grace; that, after the cloth was removed, the anniversary anthem, as they impiously called it, was sung, and a calf's skull filled with wine, or other liquor, and then a brimmer, went round to the pious memory of those worthy patriots who had killed the tyrant, and delivered the country from his arbitrary sway.' Such is the story told in the edition of 1703; but in the edition of 1713, after the word, Moorfields, the narrative is continued as follows: 'where an axe was hung up in the clubroom, and was reverenced as a principal symbol in this diabolical sacrament. Their bill of fare was a large dish of calves'-heads, dressed several ways, by which they represented the king, and his friends who had suffered in his cause; a large pike with a small one in his mouth, as an emblem of tyranny; a large cod's head, by which they pretended to represent the person of the king singly; a boar's head, with an apple in its mouth, to represent the king. . . . After the repast was over, one of their elders presented an Ikon Basilike, which was with great solemnity burned upon the table, whilst the anthems were singing. After this, another produced Milton's Defensio Populi Anglicani, upon which all laid their hands, and made a protestation, in form of an oath, for ever to stand by and maintain the same. The company wholly consisted of Ana-baptists,' &c. As a specimen of the verses, the following stanzas may be quoted from the anthem for 1696, in reference to Charles I: This monarch wore a peaked beard, And seemed a doughty hero, A Dioclesian innocent, And merciful as Nero. The Church's darling implement, And scourge of all the people, He swore he'd make each mother's son Adore their idol steeple; But they, perceiving his designs, Grew plaguy shy and jealous, And timely chopt his calf's head off, And sent him to his fellows. This tract appears to have excited the curiosity of the public in no small degree; for it passed, with many augmentations as valueless as the original trash, through no less than nine editions. The fifth edition, published in 1705, contains three additional songs, and is further augmented by 'Reflections' on each of the eight songs, and by 'A Vindication of the Royal Martyr Charles the First, wherein are laid open the Republicans' Mysteries of Rebellion, written in the time of the Usurpation by the celebrated Mr. Butler, author of Hudibrus; with a Character of a Presbertian, by Sir John Denham, Knight.' To a certainty the author of Hudibras never wrote anything so stupid as this 'Vindication,' nor the author of Cooper's Hill the dull verses here ascribed to him. The sixth edition is a reprint of the fifth, but has an engraving representing the members of the club seated at a table furnished with dishes such as are described in the extract above quoted, and with the axe hung up against the wainscot. A man in a priest's dress is saying grace, and four other persons are seated near him, two on each side; two others seem by their dress to be men of rank. A black personage, with. horns on his head, is looking in at the door from behind; and a female figure, with snakes among her hair, probably representing Rebellion, is looking out from under the table. The eighth edition, published in 1713, contains seven engravings, including the one just described, and the text is augmented to 224 pages. The additional matter consists of the following articles: 'An Appendix to the Secret History of the Calf's Head Chub;' Remarkable Accidents and Transactions at the Calf's Head Club, by way of Continuation of the Secret History there-of,'- these 'Accidents 'extend over the years 1708-12, and consist of narratives apparently got up for the purpose of exciting the public and selling the book; 'Select Observations of the Whigs;' 'Policy and Conduct in and out of Power.' Lowndes mentions another edition published in 1716. Hearne tells us that on the 30th January 1706-7, some young men in All Souls' College, Oxford, dined together at twelve o'clock, and amused themselves with cutting off the heads of a number of woodcocks, 'in contempt of the memory of the blessed martyr.' They had tried to get calves'-heads, but the cook refused to dress them. MEMORIALS OF CHARLES I It is pleasanter to contemplate the feelings of tenderness and veneration than those of contempt and anger. We experience a relief in turning from the coarse doings of the Calves'-Head Club, to look on the affectionate grief of those who, on however fallacious grounds, mourned for the royal martyr. It is understood that there were seven mourning rings distributed among the more intimate friends of the unfortunate king, and one of them was latterly in the possession of Horace Walpole at Strawberry Hill, being a gift to him from Lady Murray Elliott. The stone presents the profile of the king in miniature. On the obverse of this, within, is a death's head, surmounting a crown, with a crown of glory above; flanked by the words, GLORIA-VANITAS; while round the interior runs the legend, Gloria Ang Emigravit, Ja. the 30, 1648. There are also extant several examples of a small silver case or locket, in the form of a heart, which may be presumed each to have been suspended near the heart of some devoted and tearful loyalist. In the example here presented, there is an engraved profile head of the king within, opposite to which, on the inside of the lid, is inscribed, 'Prepared be to follow me, C.R.' On one of the exterior sides is a heart stuck through with arrows, and the legend, 'I live and dy in loyaltye.' On the other exterior side is an eye dropping tears, surmounted by 'Quis temperet a lacrymis, January 30, 1648.' Other examples of this mourning locket have slight variations in the ornaments and legends. CONVIVIAL CLUBS IN LANCASHIREWhat is a club? A voluntary association of persons for a common object, and contributing equally to a common purse. The etymology of the word is a puzzle. Some derive it from the Anglo-Saxon cleofan, to cleave, q. d. the members 'stick together;' but this seems a little farfetched. Others consider it as from the Welsh verb clapiaw, to form into a lump; or to join together for a common end. Whencesoever our name for it, the institution is ancient; it was known among the ancient Greeks, every member contributing his share of the expenses. They had even their benefit-clubs, with a common chest, and monthly payments for the benefit of 'members in distress. Our Anglo-Saxon fore-fathers had like confederations, only they called them gylds or guilds, from gytdan, to pay, to contribute a share. Religious guilds were succeeded by trade guilds and benevolent guilds, which were a sort of sick and burial clubs, some of which still survive. The club convivial, in essence if not in name, has always been a cherished institution amongst us. We need only name the Mermaid, of the time of Shakspeare, Ben Jonson, and their fellows. It would be an interesting inquiry to trace the succession of such clubs, in the metropolis alone, from the days of Elizabeth to those of Anne; the clubs of the latter period being so delightfully pictured to us by Addison, Steele, and others of their members. From the coffee-house clubs of the time of Charles II, including the King's Head or Green Ribbon Club of the Shaftesbury clique, it would be curious to trace the gradual development of the London clubs, into their present palatial homes at the West-end. But our task is a much more limited one. We wish to perpetuate a few of the fast-fading features of some of these institutions in a northern shire,-clubs in which what Carlyle terms the 'nexus' was a love of what was called 'good eating and drinking, and good fellowship.' What its inhabitants designate 'the good old town' of Liverpool might naturally be expected, as the great seaport of Lancashire, to stand pre-eminent in its convivial clubs. But we must confess we have been unable to find any very distinct vestiges, or even indications, of such institutions having once enjoyed there 'a local habitation and a name.' To deny to the inhabitants of Liverpool, the social character and convivial habits out of which such clubs naturally spring, would be to do them a great injustice. But the only peep we get into their habits in the latter half of the 18th century, is that afforded by some published Letters to the Earl of Cork, written by Samuel Derrick, Esq., then Master of the Ceremonies at Bath, after a visit to Liverpool in 1767. After describing the fortnightly assemblies, 'to dance and play cards;' the performances at the one theatre which then sufficed; the good and cheap entertainment provided for at Liverpool's three inns, where: 'for ten penee a man dines elegantly at an ordinary consisting of a dozen dishes,' Mr. Derrick lauds the private hospitality which he enjoyed, and the good fellowship he saw: 'If by accident one man's stock of ale runs short, he has only to send his pitcher to his neighbour to have it filled.' He celebrates the good ale of Mr. Thomas Mears, of Paradise-street, a merchant in the Portuguese trade, 'whose malt was bought at Derby, his hops in Kent, and his water brought by express order from Lisbon. 'It was, indeed,' says Derrick, 'an excellent liquor.' He speaks of the tables of the merchants as being plenteously furnished with viands well served up, and adds that, 'of their excellent rum they consumed large quantities in punch, when the West India fleet came in mostly with limes,' which he praises as being 'very cooling, and affording a delicious flavour.' Still, these are the tipplings around the private 'mahogany,' if such a material were then used for the festive board; and Mr. Derrick nowhere narrates a visit to a club. Indeed, the only relic of such. an assemblage is to be found in a confederation which existed in Liverpool for some time about the middle of the 18th century. Its title was 'The Society of Bucks.' It seems to have been principally convivial, though to some slight extent of a political complexion. On Monday, 4th June 1759, they advertise a celebration of the birthday of George Prince of Wales, (afterwards George III) On Wednesday, July 25th, their anniversary meeting is held 'by the command of the grand,'-(a phrase borrowed from the Freemasons)-dinner on the table at two o'clock. On August 3, they command a play at the theatre; and on the 8th February 1760, the Society is recorded as: 'having generously subscribed £70 towards clothing our brave troops abroad, and the relief of the widows and orphans of those who fell nobly in their country's and liberty's cause. This is the second laudable subscription made by them, as they had some time since remitted 50 guineas to the Marine Society.' From an early period in the 18th century, the amusements of the inhabitants of Manchester consisted of cards, balls, theatrical performances, and concerts. About 1720 a wealthy lady named Madam Drake, who kept one of the three or four private carriages then existing in the town, refused to conform to the new-fashioned beverages of tea and coffee; so that, whenever she made an afternoon's visit, her friends presented her with that to which she had been accustomed,-a tankard of ale and a pipe of tobacco! The usual entertainment at gentlemen's houses at that period included wet and dry sweetmeats, different sorts of cake and gingerbread, apples, or other fruits of the season, and a variety of lime-made wines, the manufacture of which was a great point with all good housewives. They made an essential part of all feasts, and were brought forth when the London or Bristol dealers came down to settle their accounts with the Manchester manufacturers, and to give orders. A young manufacturer about this time, having a valuable customer to sup with him, sent to the tavern for a pint of foreign wine, which next morning furnished a subject for the sarcastic remarks of all his neighbours. About this period there was an evening club of the most opulent manufacturers, at which the expenses of each person were fixed at 42; viz., 4d. for ale, and a halfpenny for tobacco. At a much later period, however, six-pennyworth of punch, and a pipe or two, were esteemed fully sufficient for the evening's tavern amusement of the principal inhabitants. After describing a common public-house in which a large number of respectable Manchester tradesmen met every day after dinner,-the rule being to call for six-pennyworth of punch, the amusement to drink and smoke and discuss the news of the town, it being high: 'change at six o'clock and the evening's sitting peremptorily terminated at 8 p.m.,-the writer we are quoting adds, 'To a stranger it is very extraordinary, that merchants of the first fortunes quit the elegant drawing-room, to sit in a small, dark dungeon, for this house cannot with propriety be called by a better name-but such is the force of long-established custom!' The club which originated at the house just described has some features sufficiently curious to be noted as a picture of the time. A man named John Shaw, who had served in the army as a dragoon, having lost his wife and four or five children, solaced himself by opening a public-house in the Old Shambles, Manchester; in conducting which he was ably supported by a sturdy woman servant of middle age, whose only known name was 'Molly.' John Shaw, having been much abroad, had acquired a knack of brewing punch, then a favourite beverage; and from this attraction, his house soon began to be frequented by the principal merchants and manufacturers of the town, and to be known as 'John Shaw's Punch-house. Sign it had none. As Dr. Aikin says in 1795 that Shaw had then kept the house more than fifty years, we have here an institution dating prior to the memorable '45. Having made a comfortable competence, John Shaw, who was a lover of early hours, and, probably from his military training, a martinet in discipline, instituted the singular rule of closing his house to customers at eight o'clock in the evening. As soon as the clock struck the hour, John walked into the one public room of the house, and in a loud voice and imperative tone, proclaimed 'Eight o'clock, gentlemen; eight o'clock.' After this no entreaties for more liquor, however urgent or suppliant, could prevail over the inexorable land-lord. If the announcement of the hour did not at once produce the desired effect, John had two modes of summary ejectment. He would call to Molly to bring his horsewhip, and crack it in the ears and near the persons of his guests; and should this fail, Molly was ordered to bring her pail, with which she speedily flooded the floor, and drove the guests out wet-shod. On one occasion of a county election, when Colonel Stanley was returned, the gentleman took some friends to John Shaw's to give them a treat. At eight o'clock John came into the room and loudly announced the hour as usual. Colonel Stanley said he hoped Mr. Shaw would not press the matter on that occasion, as it was a special one, but would allow him and his friends to take another bowl of punch. John's characteristic reply was: 'Colonel Stanley, you are a law-maker, and should not be a law-breaker; and if you and your friends do not leave the room in five minutes, you will find your shoes full of water.' Within that time the old servant, Molly, came in with mop and bucket, and the representative for Lancashire and his friends retired in dismay before this prototype of Dame Partington. After this eight o'clock law was established, John Shaw's was more than ever resorted to. Some of the elderly gentlemen, of regular habits, and perhaps of more leisure than their juniors, used to meet there at four o'clock in the after-noon, which they called 'watering time,' to spend each his sixpence, and then go home to tea with their wives and families about five o'clock. But from seven to eight o'clock in the evening was the hour of high 'change at John Shaw's; for then all the frequenters of the house had had tea, had finished the labours of the day, closed their mills, warehouses, places of business, and were free to enjoy a social hour. Tradition says that the punch brewed by John Shaw was something very delicious. In mixing it, he used a long-shanked silver table-spoon, like a modern gravy-spoon; which, for convenience, he carried in a side pocket, like that in which a carpenter carries his two-foot rule. Punch was usually served in small bowls (that is, less than the 'crown bowls' of later days) of two sizes and prices; a shilling bowl being termed 'a P of punch,'-'a Q of punch' denoting a sixpenny bowl. The origin of these slang names is unknown. Can it have any reference to the old saying - Mind your P's and Q's.? If a gentleman came alone and found none to join him, he called for 'a Q.' If two or more joined, they called for 'a P;' but seldom more was spent than about 6d. per head. Though eccentric and austere, John won the respect and esteem of his customers, by his strict integrity and steadfast adherence to his rules. For his excellent regulation as to the hour of closing, he is said to have frequently received the thanks of the ladies of Manchester, whose male friends were thus induced to return home early and sober. At length this nightly meeting of friends and acquaintances at John Shaw's grew into an organized club, of a convivial character, bearing his name. Its objects were not political; yet, John and his guests being all of the same political party, there was sufficient unanimity among them to preserve harmony and concord. John's roof sheltered none but stout, thorough-going Tories of the old school, genuine 'Church and King' men; nay, even 'rank Jacobites.' If perchance, from ignorance of the character of the house, any unhappy Whig, any unfortunate partisan of the house of Hanover, any known member of a dissenting conventicle, strayed into John Shaw's, he found himself in a worse position than that of a solitary wasp in a beehive. If he had the temerity to utter a political opinion, he speedily found 'the house too hot to hold him,' and was forthwith put forth into the street. When the club was duly formed, a President was elected; and there being some contest about a Vice-President, John Shaw summarily abolished that office, and the club had perforce to exist without its 'Vice.' The war played the mischief with John's inimitable brew; limes became scarce; lemons were substituted; at length of these too, and of the old pine-apple rum of Jamaica, the supplies were so frequently cut off by French privateers, that a few years before John Shaw's death, the innovation of 'grog' in place of punch struck a heavy blow at the old man's heart. Even autocrats must die, and at length, on the 26th January 1796, John Shaw was gathered to his fathers, at the ripe old age of eighty-three, having ruled his house upwards of fifty-eight years; namely, from the year 1738. But though John Shaw ceased to rule, the club still lived and flourished. His successor in the house carried on the same 'early closing movement,' with the aid of the same old servant Molly. At length the house was pulled down, and the club was very migratory for some years. It finally settled down in 1852, in the Spread Eagle Hotel, Corporation-street, where it still prospers and flourishes. From the records of the club, which commenced in 1822 and extend to the present time, it appears that its government consists of a President, a Vice-President, a Recorder [i. e.. Secretary], a Doctor [gene-rally some medical resident of 'the right sort'], and a Poet Laureate: these are termed 'the staff;' its number of members fluctuates between thirty and fifty, and it still meets in the evenings, its sittings closing, as of old, at curfew. Its presidents have included several octogenarians; but we do not venture to say whether such longevity is due to its punch or its early hours. Its present president, Edmund Buckley, Esq., was formerly (1841-47) M.P. for Newcastle-under-Lyne; he has been a member of the club for nearly forty years, and he must be approaching the patriarchal age of some of his predecessors. In 1834, John Shaw's absorbed Into its venerable bosom another club of similar character, entitled 'The Sociable Club.' The club possesses amongst its relics oil paintings of John Shaw and his maid Molly, and of several presidents of past years. A. few years ago, a singular old China punch-bowl, which had been the property of John Shaw himself, was restored to the club as its rightful property, by the descendant of a trustee. It is a barrel-shaped vessel, suspended as on a stillage, with a metal tap at one end, whence to draw the liquor; which it received through a large opening or bung-hole. Besides assembling every evening, winter and summer, between five and eight o'clock, a few of the members dine together every Saturday at 2 p.m.; and they have still an annual dinner, when old friends and members drink old wine, toast old toasts, tell old stories, or 'fight their battles o'er again.' Such is John Shaw's club-nearly a century and a quarter old, in the year of grace 1862. From a punch-drinking club we turn to a dining club. About the year 1806 a few Manchester gentlemen were in the habit of dining together, as at an ordinary, at what was called 'Old Froggatt's,' the Unicorn Inn, Church-street, High-street. They chiefly consisted of young Manchester merchants and tradesmen, just commencing business and keen in its pursuit, with some of their country customers. They rushed into the house, about one o'clock, ate a fourpenny pie, drank a glass of ale, and rushed off again to 'change and to business. At length it begun to be thought that they might just as well dine off a joint; and this was arranged with host and hostess, each diner paying a penny for cooking and twopence for catering and providing. The meal, however, continued to be performed with wonderful dispatch, and one of the traditionary stories of the society is that, a member one day, coming five minutes behind the hour, and casting a hasty glance through the window as he approached, said disappointedly to a friend, 'I need not go in-all their necks are up! 'As soon as dinner was over, Old Froggatt was accustomed to bring in the dinner bill, in somewhat primitive fashion. Instead of the elegant, engraved form of more modern times, setting forth how many 'ports,' 'sherries,' 'brandies,' 'gins,' and 'cigars,' had been swallowed or consumed,-Froggatt's record was in humble chalk, marked upon the loose, unhinged lid of that useful ark in old cookery, the salt-box. A practical joke perpetrated one day on this cretaceous account, and more fitted for ears of fifty years ago than those now existing, led to a practice which is still kept up of giving as the first toast after every Tuesday's dinner at the club, 'The Salt-box lid,'-a cabala which usually causes great perplexity to the uninitiated guest. About Christmas 1810, these gentlemen agreed to form themselves into a regular club. Having to dine in a hurry and hastily to return to business, the whole thing had much the character of every one scrambling for what he could get; and the late Mr. Jonathan Peel, a cousin of the first Sir Robert, and one of its earliest members, gave it in joke the name of the 'Scramble Club,' which was felt to be so appropriate, that it was at once adopted for the club's title, and it has borne the name ever since. The chief rule of the club was, that every member should spend sixpence in drink for the good of the house; and the law was specially levelled against those 'sober-sides' who would otherwise have sneaked off with a good dinner, washed down with no stronger potations than could be supplied by the pump of the Unicorn. The club had its staff of officers, its records and its register; but alack! incautiously left within the reach of servants, the first volume of the archives of the ancient and loyal Scramblers served the ignoble purpose of lighting the fires of an inn. We are at once reminded of the great Alexandrian library, whose MS. treasures fed the baths of the city with fuel for more than eight months! The club grew till the Unicorn could no longer accommodate its members; and after various flittings' from house to house, it finally folded its wings and alighted under the hospitable roof of the Clarence Hotel, Spring-gardens; where it still, 'nobly daring, dines,' and where the dinners are too good to be scrambled over. Amongst the regalia of the club are some portraits of its founder and early presidents, a very elaborately carved snuff-box, &c. The members dine together yearly in grand anniversary. Amongst the laws and customs of the club, was a system of forfeit, or fines. Thus if any member removed to another house, or married, or became a father, or won a prize at a horse-race, he was mulcted in one, two, or more bottles of wine, for the benefit of the club. Again, there were odd rules (with fines for infraction) as to not taking the chair, or leaving it to ring a bell, or asking a stranger to ring it, or allowing a stranger to pay anything. These delinquencies were formally brought before the club, as charges, and if proved, a fine of a bottle or more followed; if not proved, the member bringing the charge forfeited a bottle of wine. There were various other regulations, all tending to the practical joking called 'trotting,' and of course resulting in fines of wine. Leaving the Scramble Club to go on dining, as it has done for more than half a century, we come next to a convivial club in another of the ancient towns of Lancashire-'Proud Preston.' It seems that from the year 1771 down to 1841, a period of seventy years, that town boasted its 'Oyster and Parched Pea Club.' In its early stages the number of its members was limited to a dozen of the leading inhabitants; but, like John Shaw's Club, they were all of the same political party, and they are said to have now and then honoured a Jacobite toast with a bumper. It possesses records for the year 1773, from which we learn that its president was styled 'the Speaker.' Amongst its staff of officers was one named Oystericus, 'whose duty it was to order and look after the oysters, which then came 'by fleet' from London; a Secretary, an Auditor, a Deputy Auditor, and a Poet Laureate, or 'Rhymesmith,' as he was generally termed. Among other officers of later creation, were the 'Cellarius,' who had to provide 'port of first quality,' the Chaplain, the Surgeon-general, the Master of the Rolls (to look to the provision of bread and butter), the 'Swig-Master,' whose title expresses his duty, Clerk of the Peas, a Minstrel, a Master of the Jewels, a Physician-in-Ordinary, &c. Among the Rules and Articles of the club, were 'That a barrel of oysters be provided every Monday night during the winter season, at the equal expense of the members; to be opened exactly at half-past seven o'clock.' The bill was to be called for each night at ten o'clock, each. member present to pay an equal share. 'Every member, on having a son horn, shall pay a gallon-for a daughter half a gallon-of port, to his brethren of the club, within a month of the birth of such child, at any public-house he shall choose.' Amongst the archives of the club is the following curious entry, which is not in a lady's hand: 'The ladies of the Toughey [? Toffy] Club were rather disappointed at not receiving, by the hands of the respectable messenger, despatched by the still more respectable members, of the Oyster Club, a few oysters. They are just sitting down, after the fatigues of the evening, and take the liberty of reminding the worthy members of the Oyster Club, that oysters were not made for man alone. The ladies have sent to the venerable president a small quantity of sweets [? pieces of Everton toffy] to be distributed, as he in his wisdom shall think fit. It does not appear what was the result of this pathetic appeal and sweet gift to the venerable president of the masculine society. In 1795 the club was threatened with a difficulty, owing, as stated by 'Mr. Oystericus,' to the day of the wagon-laden with oysters-leaving London having been changed. Sometimes, owing to a long frost, or other accident, no oysters arrived, and then the club must have solaced itself with. 'parched peas' and 'particular port.' Amongst the regalia of the club was a silver snuff box, in the lid of which was set a piece of oak, part of the quarter-deck of Nelson's ship Victory. On one occasion the master of the jewel-office, having neglected to replenish this box with snuff, was fined a bottle of wine. At another time (November 1816), the Clerk of the Peas was reprimanded for neglect of duty, there being no peas supplied to the club. The Rhymesmith's poetical effusions must provoke a laugh by local allusion; but they are scarcely good enough to record here, at least at length. A few of the best lines may be given, as a sample of the barrel: A something monastic appears amongst oysters, For gregarious they live, yet they sleep in their cloisters; 'Tis observed too, that oysters, when placed in their barrel, Will never presume with their stations to quarrel. From this let us learn what an oyster can tell us, And we all shall be better and happier fellows. Acquiesce in your stations, whenever you've got 'em; Be not proud at the top, nor repine at the bottom, But happiest they in the middle who live, And have something to lend, and to spend, and to give. The Bard would fain exchange, clack For precious gold, his crown of laurel; His sacicbut for a butt of sack, His vocal shell for oyster barrel. Three lines for an ode in 1806: Nelson has made the seas our own, Then gulp your well-fed oysters down, And give the French the shell. Such were and are some of the Convivial Clubs of Lancashire in the last or present century. Doubtless, similar institutions have existed, and may still exist, in other counties of England. If so, let some of their Secretaries, Recorders, or Rhymesmiths tell in turn their tale. J. H. |