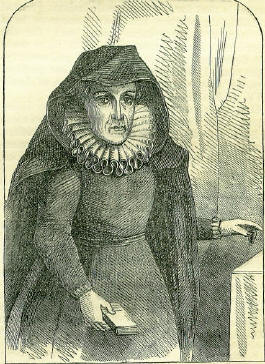

28th FebruaryBorn: Michael de Montaigne, essayist, 1533, Perigord; Henry Stubbe, 'the most noted Latinist and Grecian of his age,' 1631, Partney; Dr. Daniel Solander, naturalist, 1736, Nordland, Sweden. Died: Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, murdered, 1447, St. Albans; George Buchanan, historian, 1582, Edinburgh; Christian IV. (of Denmark), 1646; Edward Moore, dramatist, 1757; Dr. Richard Grey, 1771. Feast Days: Martyrs who died of the great pestilence in Alexandria, 261-3. St. Romanus, about 460, and St. Lupicinus, abbots, 479. St. Proterius, patriarch of Alexandria, martyr, 557 MRS. SUSAN CROMWELL On the 28th of February 1834, died, at the age of ninety, Mrs. Susan Cromwell, youngest daughter of Thomas Cromwell, Esq., the great-grandson of the Protector. She was the last of the Protector's descendants who bore his name. The father of this lady, whose grandfather, Henry Cromwell, had been Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, spent his life in the modest business of a grocer on Snow-hill; he was, however, a man of exemplary worth, fit to have adorned a higher station. His father, who was a major in King William's army, had been born in Dublin Castle during his father's lieutenancy. It may be remarked that the family of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell was one of good account, his uncle and godfather, Sir Oliver Cromwell, possessing estates in Huntingdon-shire alone which were afterwards worth £30,000 a-year. The Protector's mother, by an odd chance, was named Stewart; but it is altogether imaginary that she bore any traceable relationship to the royal family. The race was originally Welsh, and bore the name of Williams; but the great-grandfather of the Protector changed it to Cromwell, in compliance with a wish of Henry VIII, taking that particular name in honour of his relation, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex. INSTITUTION OF THE ORDER OF ST. PATRICKOn the 28th of February 1783, George III signed at St. James's the statutes constituting the Order of St. Patrick. The forming of this order of knighthood was prompted by the recent appearances of a national Irish spirit which would no longer sit patiently under neglect and misgovernment. It was thought by the new cabinet of Lord Shelburne a good policy to seek to conciliate the principal peers of Ireland by conferring marks of distinction upon them. The whole arrangements were after the model of those of the Order of the Garter. Besides the King as 'Sovereign,' there were a Grand Master, and fifteen Companions (since extended to twenty-two), besides a Chancellor, a Registrar, a Secretary, a Genealogist, an Usher, and a King-at-Arms, a Prelate being afterwards added. The first companions elected were the Prince Edward (afterwards Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria), the Duke of Leinster, and thirteen Earls of Ireland, amongst whom was the Earl of Mornington, afterwards Marquis Wellesley, eldest brother of the Duke of Wellington. Proper dresses and insignia were ordered for the knights and officers, and the hall of Dublin Castle, under the new name of St. PATRICK'S HALL, was assigned as their place of meeting. It was designed, of course, as a concession to the national feelings, that the order was named from St. Patrick, the tutelar saint of Ireland, and that the cross of St. Patrick (a red saltire), and a golden harp, the ancient Irish ensign, together with the national badge, the shamrock or trefoil, to which the saint had given celebrity, were made its principal symbols. It will surprise no one, not even amongst the people of the sister island itself, and probably it will amuse many, that a few anomalous circumstances attended the formation of the order of St. Patrick. First, the saint's 'day' was not chosen for the institution of the order, and is not celebrated by them. Second, the Grand Master, though entitled to preside in absence of the sovereign, is not necessarily a member of the order. Further, the secretary has no duties (though he draws fees); the letters patent of foundation are not known to exist (no one can tell if they ever passed the great seal either of England or Ireland); and there are no arrangements for degradation or expulsion. ODDITIES OF FAMILY HISTORYHuman life and its relations have certain tolerably well-marked bounds, which, however, are sometimes overpassed in a surprising manner. One of the most ancient observations regarding human life, and one yet found acceptable to our sense of truth, is that a life passed healthily, and unexposed to disastrous accident, will probably extend to seventy years. Another is that there are usually just about three generations in a century. And hence it arises that one generation is usually approaching the grave when the third onward is coming into existence:-in other words, a man is usually well through his life when his son's children are entering it, or a man's son is usually near the tomb about a hundred years after his own birth,-a century rounding the mortal span of two generations and seeing a third arrived at the connubial period. It is well known, nevertheless, that some men live much. beyond seventy years, and that more than three generations are occasionally seen in life at one time. Dr. Plot, in his Natural History of Staffordshire, 1686, gives many instances of centenarians of his time, and of persons who got to a few years beyond the hundred,-how far well authenticated we cannot tell. He goes on to state the case of 'old Mary Cooper of King's Bromley in this county, not long since dead, who lived to be a beldam, that is, to see the sixth generation, and could say the same I have, 'says he, 'heard reported of another, viz. 'Rise up, daughter, and go to thy daughter, for thy daughter's daughter hath a daughter;' whose eldest daughter Elizabeth, now living, is like to do the same, there being a female of the fifth generation near marriageable when I was there. Which is much the same that Zuingerus reports of a noble matron of the family of Dolburges, in the archbishopric of Mentz, who could thus speak to her daughter: '(1) Mater ait (2) natu, Dic (3) natse, Filia, (4) natam Ut moveat, (5) natae flangere (6) filiolam.' 'That is, the mother said to her daughter, daughter bid thy daughter tell her daughter, that her daughter's daughter cries.' He adduces, as a proof how far this case is from being difficult of belief, that a Lady Child of Shropshire, being married at twelve, had her first baby before she was complete thirteen, and this being repeated in the second generation, Lady Child found herself a grandmother at twenty-seven! At the same rate, she might have been a beldam at sixty-six; and had she reached 120, as has been done by others, it was possible that nine generations might have existed together! Not much less surprising than these cases is one which Horace Walpole states in a letter dated 1785 to his friend Horace Mann: 'There is a circumstance,' he says, 'which makes me think myself an antediluvian. I have literally seen seven descents in one family. . . I was school-fellow of the two last Earls of Waldegrave, and used to go to play with them in the holidays, when I was about twelve years old. They lived with their grandmother, natural daughter of James II. One evening when I was there, came in her mother Mrs. Godfrey, that king's mistress, ancient in truth, and so superannuated, that she scarce seemed to know where she was. I saw her another time in her chair in St. James's Park, and have a perfect idea of her face, which was pale, round, and sleek. Begin with her; then count her daughter, Lady Waldegrave; then the latter's son the ambassador; his daughter Lady Harriet Beard; her daughter, the present Countess Dowager of Powis, and her daughter Lady Clive; there are six, and the seventh now lies in of a son, and might have done so six or seven years ago, had she married at fourteen. When one has beheld such a pedigree; one may say, 'And yet I am not sixty-seven!'' While two generations, moreover, are usually disposed of in one hundred years, there are many instances of their extending over a much longer space of time. In our late article on the connection of distant ages by the lives of individuals, the case of James Horrox was cited, in which. the father was born in 1657, and the son died in 1844, being eighty-seven years beyond the century. Benjamin Franklin, who died in 1790, was the grandson of a man who had been born in the sixteenth century, during the reign of Elizabeth, three generations thus extending over nearly two centuries. The connubial period of most men is eminently between twenty-eight and forty; but if men delay marriage to seventy, or undertake second or third nuptials at that age with young women-both of them events which sometimes happen-it must arise, as a matter of course, that not a century, but a century and a half, or even more, will become the bounds of two generations. The following instance speaks for itself. 'Wednesday last,' says the Edinburgh Courant of May 3, 1766, 'the lady of Sir William Nicolson, of Glenbervy, was safely delivered of a daughter. What is very singular, Sir William is at present ninety-two years of age, and has a daughter alive of his first marriage, aged sixty-six. He married his present lady when he was eighty-two, by whom he has now had six children.' If the infant here mentioned had survived to ninety-two also, she might have said at her death, in 1858, 'y father was born a hundred and eighty-four years ago, in the reign of Charles II' There are also average bounds to the number of descendants which a man or a woman may reckon before the close of life. To see three, four, or five children, and three or four times the number of grandchildren, are normal experiences. Some pairs, however, as is well known, go much beyond three, four, or five. Some marry a second, or even a third time, and thus considerably extend the number of the immediate progeny. In these cases, of course, the number of grandchildren is likely to be greatly extended. Particular examples are on record, that are certainly calculated to excite a good deal of surprise. Thus we learn from a French scientific work that the wife of a baker at Paris produced one-and-twenty children-at only seven births, moreover, and in the space of seven years! Boyle tells of a French advocate of the sixteenth century who had forty-five children. He is, by-the-bye, spoken of as a great water-drinker-'aquae Tiraquellus amator.' We learn regarding Catherine Leighton, a lady of the time of Queen Elizabeth, that she married in succession husbands named Wygmore, Lymmer, Collard, and Dodge, and had children by all four; but we do not learn how many. Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty and his wife Helen Abernethy-the grandparents of that singular genius Sir Thomas Urquhart, the translator of Rabelais-are stated to have had thirty-six children, twenty-five of them sons, and they lived to see the whole of this numerous progeny well provided for. 'The sons were men of great reputation, partly on account of their father's, and partly for their own personal merits. The daughters were married in families not only equal to their quality, but of large, plentiful estates, and they were all of them (as their mother had been) very fruitful in their issue.' Thomas Urquhart, who lived in the early part of the sixteenth century, built for himself a lofty, many-turreted castle, with sundry picturesque and elegant features, which Hugh Miller has well described in his account of Cromarty, but which was unfortunately taken down in 1772. It was also remembered of this many-chilled laird, that he used to keep fifty servants. The entire population of Cromarty Castle must therefore have been considerable. Notwithstanding the great expense thus incurred, the worthy laird died free of debt, and transmitted the family property unimpaired to his posterity. As to number of descendants, two cases in the annals of English domestic life come out very strongly. First, there was Mrs. Honeywood of Charing, in Kent, who died on the 10th of May 1620, aged ninety-three, having had sixteen children, a hundred and fourteen grandchildren, two hundred and twenty-eight great-grandchildren, and nine great-great-grandchildren. Dr. Michael Honeywood, dean of Lincoln, who died in 1681, at the age of eighty-five, was one of the grandchildren. The second instance was even more wonderful. It represents Lady Temple of Stow, as dying in 1656, having given birth to four sons and nine daughters, and lived to see seven hundred descendants. In as far as life itself goes in some instances considerably beyond an average or a rule, so does it happen that men occasionally hold office or practise a profession for an abnormally long time. Hearne takes notice of a clergyman, named Blower, who died in 1643, vicar of White-Waltham, which office he had held for sixty-seven years, though it was not his first cure. 'It was said he never preached but one sermon in his life, which was before Queen Elizabeth. Going after this discourse to pay his reverence to her Majesty, he first called her My Royal Queen, and afterwards My Noble Queen; upon which Elizabeth smartly said, 'What! am I ten groats worse than I was?' Blower was so mortified by this good-natured joke, that he vowed to stick to the homilies for the future.' The late Earl of Aberdeen had enjoyed the honours of his family for the extraordinary period of sixty years,-a fact not unexampled, however, in the Scottish peerage, as Alexander, ninth Earl of Caithness, who died in 1765, had been peer for an equal time, and Alexander, fourth Duke of Gordon, was duke for seventy-five years, namely from 1752 to 1827. It is perhaps even more remarkable that for the Gordon dukedom, granted in 1684, there were but four possessors in a hundred and forty-three years, and for the Aberdeen earldom, granted in 1682, there were but four possessors in a hundred and seventy-eight years ! In connection with these particulars, we may advert to the long reign of Louis XIV of France-seventy-two years. Odd matrimonial connections are not infrequent. For example, a man will marry the niece of his son's wife. Even to marry a grandmother, though both ridiculous and illegal, is not unexampled (the female, however, being not a blood relation). 'Dr. Bowles, doctor of divinity, married the daughter of Dr. Samford, doctor of physic, and, vice versa, Dr. Samford the daughter of Dr. Bowles; whereupon the two women might say, These are our fathers, our sons, and our husbands.'-Arch. Usher's MSS. Collections, quoted in Reliquiae Hearnianae, i. 124. The rule in matrimonial life where no quarrel has taken place is to continue living together. Yet we know that in this respect there are strange eccentricities. From the biography of our almost divine Shakspeare, it has been inferred that, on going to push, his fortune in London, he left his Anne Hathaway (who was eight years his senior) at Stratford, where she remained during the sixteen or seventeen years which he spent as a player and play-writer in the metropolis; and it also appears that, by and by returning there as a man of gentlemanly means, he resumed living with Mrs. Shakspeare, as if no sort of alienation had ever taken place between them. There is even a more curious, and, as it happens, a more clear case, than this, in the biography of the celebrated painter, George Romney. He, it will be remembered, was of peasant birth in Lancashire. In 1762, after being wedded for eight years to a virtuous young woman, he quitted his home in the north to try his fortune as an artist in London, leaving his wife behind him. There was no quarrel-he supplied her with ample means of support for herself and her two children out of the large income he realized by his profession; but it was not till thirty-seven years had passed, namely, in 1799, when he was sixty-five, and broken in health, that the truant husband returned home to resume living with his spouse. It is creditable to the lady, that she was as kind to her husband as if he had never left her; and Romney, for the three or four years of the remainder of his life, was as happy in her society as ill health would permit. It is a mystery which none of the great painter's biographers, though one of them was his son, have been able to clear up. THE RACE-HORSE ECLIPSEOn the 28th of February 1789, died at Canons, in Middlesex, the celebrated horse Eclipse, at the advanced age of twenty-five. The animal had received his name from being born during an eclipse, and it became curiously significant and appropriate when, in mature life, he was found to surpass all contemporary horses in speed. He was bred by the Duke of Cumberland, younger brother of George III, and afterwards became the property of Dennis O'Kelly, Esq., a gentleman of large fortune, who died in December 1787, bequeathing this favourite horse and another, along with all his brood mares, to his brother Philip, in whose possession the subject of this memoir came to his end. For many years, Eclipse lived in retirement from the turf, but in another way a source of large income to his master, at Clay Hill, near Epsom, whither many curious strangers resorted to see him. They used to learn with surprise, -for the practice was not common then, as it is now,-that the life of Eclipse was insured for some thousands of pounds. When, after the death of Dennis O'Kelly, it became necessary to remove Eclipse to Canons, the poor beast was so worn out that a carriage had to be constructed to carry him. The secret of his immense success in racing was revealed after death in the unusual size of his heart, which weighed thirteen pounds. |