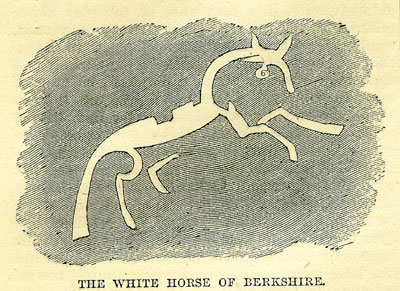

28th DecemberBorn: Thomas Henderson, astronomer, 179S, Dundee; Alexander Keith Johnstone, geographer, 1804. Died: Mary of Orange, Queen of William III, 1694, Kensington; Pierre Bayle, critic and controversialist, 1706, Rotterdam; Joseph Piton de Tournefort, distinguished botanist, 1708, Paris; Dr. John Campbell, miscellaneous writer, 1775, London; John Logan, poet, 178S, London; Thomas Babington Macaulay, Lord Macaulay, historian, essayist, &c., 1859, Kensington. Feast Day: St. Theodorus, abbot of Tabenna, confessor, 667. INNOCENT'S DAYThis festival, which is variously styled Innocents' Day, The Holy Innocents' Day, and Childermas Day, or Childermas, has been observed from an early period in the history of the church, as a commemoration of the barbarous massacre of children in Bethlehem, ordered by King Herod, with the view of destroying among them the infant Saviour, as recorded in the Gospel of St. Matthew. It is one of those anniversaries which were retained in the ritual of the English Church at the Reformation. In consequence probably of the feeling of horror attached to such an act of atrocity, Innocents' Day used to be reckoned about the most unlucky through-out the year, and in former times, no one who could possibly avoid it, began any work, or entered on any undertaking, on this anniversary. To marry on Childermas Day was especially inauspicious. It is said of the equally superstitious and unprincipled monarch, Louis XI., that he would never perform any business, or enter into any discussion about his affairs on this day, and to make to him then any proposal of the kind, was certain to exasperate him to the utmost. We are informed, too, that in England, on the occasion of the coronation of King Edward IV, that solemnity, which had been originally intended to take place on a Sunday, was postponed till the Monday, owing to the former day being in that year the festival of Childermas. This idea of the inauspicious nature of the day was long prevalent, and is even yet not wholly extinct. To the present hour we understand the housewives in Cornwall, and probably also in other parts of the country, refrain scrupulously from scouring or scrubbing on Innocents' Day. In ancient times, the 'Massacre of the Innocents' might be said to be annually re-enacted in the form of a smart whipping, which it was customary on this occasion to administer to the juvenile members of a family. We find it remarked by an old writer, that: 'it hath been a custom, and yet is elsewhere, to whip up the children upon Innocents' Day Morning, that the memory of Herod's murder of the Innocents might stick the closer, and in a moderate proportion to act over the crueltie again in kinde.' Several other ancient authors confirm the accuracy of this statement. The idea is naturally suggested that these unfortunate 'innocents' might have escaped so disagreeable a commemoration by quitting their couches betimes, before their elders had risen, and we accordingly find that in some places the whole affair resolved itself into a frolic, in which the lively and active, who managed to be first astir, made sport to themselves at the expense of the lazy and sleepy-headed, whom it was their privilege on this morning to rouse from grateful slumbers by a sound drubbing administered in lecto. In reference to the three consecutive commemorations, on the 26th, 27th, and 28th of December, theologians inform us that in these are comprehended three descriptions of martyrdom, all of which have their peculiar efficacy, though differing in degree. In the death of St. Stephen, an example is furnished of the highest class of martyrdom; that is to say, both in will and deed. St. John the Evangelist, who gave practical evidence of his readiness to suffer death for the cause of Christ, though, through miraculous interposition, he was saved from actually doing so, is an instance of the second description of martyrdom-in will though not in deed. And the slaughter of the Innocents affords an instance of martyrdom in deed and not in will, these unfortunate children having lost their lives, though involuntarily, on account of the Saviour, and it being therefore considered 'that God supplied the defects of their will by his own acceptance of the sacrifice.' JOHN LOGANThe name of John Logan, though almost entirely forgotten in South Britain, is not likely to pass into oblivion in Scotland, as long as the church of that country continues to use in her services those beautiful Scripture paraphrases and hymns, undoubtedly the finest and most poetical of any versified collection of chants for divine worship employed by any denomination of Christians in the United Kingdom. Some of the finest of these, including the singularly solemn and affecting hymn, The hour of my departure's come,' are from the pen of Logan. The history of this gifted man forms one of those melancholy chapters which the lives of men of genius have but too often furnished. The son of a small farmer near Pala, in Mid-Lothian, he was educated for the Scottish Church in the Edinburgh University, and almost immediately after being licensed as a preacher, was presented to a church in Leith, where for several years he enjoyed great renown as an eloquent and popular preacher. He delivered a course of lectures in Edinburgh with much success on the Philosophy of History, published a volume of poems, and had a tragedy called Runnamede acted at the Edinburgh theater in 1783. The times were now somewhat changed since the days when the production of Home's Tragedy of Douglas had excited a ferment in the Scottish Church, which has become historical. We are informed by Dr. Carlyle, who himself had to encounter the violence of the storm which burst forth against Home and the clerical brethren who supported him, that about 1784, so complete a revulsion of feeling had taken place on the subject of theatricals, owing to the predominance gained by the Moderate over the Evangelical party, that when Mrs. Siddons made her first appearance in Edinburgh, the General Assembly of the Scottish Church was obliged to adjourn its sittings at an early hour to enable its reverend members to attend the theater and witness the performance of the great tragic actress. Yet, notwithstanding this altered state of public opinion, Logan did undergo some obloquy and animadversion in consequence of the play above referred to, and the annoyance thereby occasioned, combined with a hereditary tendency to hypochondria, seems to have induced a melancholy and depression of spirits which prompted him to seek relief in the fatal solace of stimulating liquors. The habit rapidly gained strength; and having so far forgotten himself as on one occasion to appear in the pulpit in a state of intoxication, the misguided man was glad to make an arrangement with the ecclesiastical authorities, by which he was allowed to resign his ministerial charge, and retain for his maintenance a portion of its revenues. He then proceeded to London, where he eked out his income by literary labour of various kinds, but did not long survive his transference to the metropolis, dying there on 28th December 1788. Two posthumous volumes of his sermons long enjoyed great popularity. Whilst yet a student at Edinburgh College, Logan acted for a lime as tutor to a boy who afterwards became Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster, famous for his many public-spirited undertakings. The following anecdote of this period of his life exhibits an amusing instance of a tendency to practical joking in the disposition of the future divine anal poet. About 1766, the Sinclair family, with whom he resided, made a progress from Edinburgh to its remote Caithness home; and owing to the badness of the roads, it was necessary to employ two carriages, the heaviest of them drawn by six horses. 'When the cavalcade reached Kinross, the natives gathered round in crowds to gaze upon it, and requested the tutor to inform them who was traveling in such state. Logan affected a suspicious reluctance to give an answer; but at last took aside some respectable bystander, and, after enjoining secrecy, whispered to him, pointing to the laird: 'You observe a portly stout gentleman, with gold lace upon his clothes. That is (but it must not be mentioned to mortal) the great Duke William of Cumberland; he is going north incog. to see the field of Culloden once more.' This news was, of course, soon spread, and brought the whole population to catch a glimpse of the hero.' THE WHITEHORSE OF BERKSHIREIn a previous article, we took occasion to describe the celebrated Berkshire monument known as 'Wayland Smith's Cave,' the history of which is shrouded in a mysterious antiquity. About a mile from this famous cromlech exists a no less remark-able memorial of bygone times-the renowned White Horse of Berkshire.  The colossal representation which bears this name, consists of a trench, about two feet deep, cut in the side of a steep green hill, which is called White Horse Hill, and rises on the south of the vale known as the Vale of the White Horse. It is situated in the parish of Uflington, in the western district of Berkshire, about five miles from Great Farringdon. Though rudely cut, the figure, excavated in the chalk of which the hill is composed, presents, when viewed from the vale beneath, a sufficiently recognizable delineation of a white horse in the act of galloping. Its length is about 374 feet, and the space which it occupies is said to be nearly two acres. No exact evidence can be adduced regarding the origin of this remarkable figure, but there seems to be little doubt that, in accordance with the popular tradition, it was carved to commemorate the victory of King Ethelred and his brother Alfred, afterwards Alfred the Great, over the Danes at Ashdown, in the year 871. The actual site of this great battle is not known, and has been the subject of some discussion; but the balance of probability is in favour of its having been fought in the neighbourhood of White Horse Hill, on the summit of which, at the height of 893 feet above the sea, is an ancient encampment, consisting of a plain of more than eight acres in extent, surrounded by a rampart and ditch. This enclosure is called Uffington Castle, and immediately beneath it is the stupendous engraving of the White Horse. Were the preservation of this curious monument dependent only on the persistency of the original figure, it would probably have long since been obliterated by the washing down of debris from above into the trench, and the gradual formation of turf. From time immemorial, however, a custom has existed among the inhabitants of the neighbouring district, of assembling periodically, and scouring or cleaning out the trench, so as to renew and preserve the figure of the horse. This ceremony is known as 'The Scouring of the White Horse,' and, according to an ancient custom, the scourers are entertained at the expense of the lord of the manor. The festival which concludes their labours, forms a fete of one or two days' duration. Rustic and athletic games of various kinds, including wrestling, backsword-play, racing, jumping, and all those pastimes included in the general category of ' old English sports,' are engaged in on this occasion with immense enthusiasm, and prizes are distributed to the most successful competitors. A most interesting and graphic description of one of these rural gatherings, which took place in September 1857, is given in The Scouring of the White Horse, from the spirited pen of Mr. Hughes, the well-known author of Tom Brown's School-days. CARD-PLAYING AND PLAYING-CARDSA universal Christmas custom of the olden time was playing at cards; persons who never touched a card at any other season of the year, felt bound to play a few games at Christmas. The practice had even the sanction of the law. A prohibitory statute of Henry VII's reign, forbade card-playing save during the Christmas holidays. Of course, this prohibition extended only to persons of humble rank; Henry's daughter, the Princess Margaret, played cards with her suitor, James IV of Scotland; and James himself kept up the custom, receiving from his treasurer, at Melrose, on Christmas-night, 1496, thirty-five unicorns, eleven French crowns, a ducat, a ridare, and a lea, in all about equal to £42 of modern money, to use at the card-table. One of Poor Robin's rhythmical effusions runs thus: Christmas to hungry stomachs gives relief, With mutton, pork, pies, pasties, and roast-beef; And men, at cards, spend many idle hours, At loadum, whisk, cross-ruff, put, and all-fours. Palamedes, it is said, invented the game of chess to assuage the bitter pangs of hunger, during the siege of Troy; and, similarly, Poor Robin, in another doggerel rhyme, seems to imply that a pair -an old name for a pack-of cards may even cheer a comfortless Christmas - The kitchen that a-cold may he, For little fire you in it may see. Perhaps a pair of cards is going, And that's the chiefest matter doing. The immortal Sir Roger De Coverley, however, took care to provide both creature-comfort and amusement for his neighbours at Christmas; by sending 'a string of hog's puddings and a pack of cards' to every poor family in the parish. Primero was the fashionable game at the court of England during the Tudor dynasty. Shakespeare represents Henry VIII playing at it with the Duke of Suffolk; and Falstaff says: 'I never prospered, since I forswore myself at Primero.' In the Earl of Northumberland's letters about the Gunpowder-plot, it is noticed that Joscelin Percy was playing at this game on Sunday, when his uncle, the conspirator, called on him at Essex House. In the Sidney papers, there is an account of a desperate quarrel between Lord Southampton, the patron of Shakespeare, and one Ambrose Willoughby. Lord Southampton was then 'Squire of the Body' to Queen Elizabeth, and the quarrel was occasioned by Willoughby persisting to play with Sir Walter Raleigh and another at Primero, in the Presence Chamber, after the queen had retired to rest, a course of proceeding which Southampton would not permit. Primero, originally a Spanish game, is said to have been made fashionable in England by Philip of Spain, after his marriage with Queen Mary. Rogers elegantly describes the fellow-voyagers of Columbus engaged at this game: At daybreak might the caravels be seen, Chasing their shadows o'er the deep serene; Their burnished prows lashed by the sparkling-tide, Their green-cross standards waving far and wide. And now once more, to better thoughts inclined, The seaman, mounting, clamoured in the wind. The soldier told his tales of love and war; The courtier sung-sung to his gay guitar. Round at Primero, sate a whiskered band; So fortune smiled, careless of sea or land. Maw succeeded Primero as the fashionable game at the English court. Sir John Harrington notices it as: Maw, A game without civility or law; An odious play, and yet in court oft seen, A saucy Knave to trump both King and Queen. Maw was the favourite game of James I, who appears to have played at cards, just as he played with affairs of state, in an indolent manner; requiring in both cases some one to hold his cards, if not to prompt him what to play. Weldon, alluding to the poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury, in his Court and Character of King James, says: 'The next that came on the stage was Sir Thomas Monson, but the night before he was to come to his trial, the Icing being at the game of Maw, said: 'Tomorrow comes Thomas Monson to his trial.' 'Yea,' said the king's card-holder, 'where if he do not play his master's prize, your majesty shall never trust me.' This so ran in the king's mind, that at the next game, he said he was sleepy, and would play out that set the next night.' The writer of a contemporary pamphlet, entitled Tom Tell-truth, shows that he was well acquainted with James's mode of playing cards, and how, moreover, his majesty was tricked in his dawdling with state matters, where the friendly services of a card-holder were less to be depended on. This pamphleteer, addressing James, observes: 'Even in the very gaming ordinaries, where men have scarce leisure to say grace, yet they take a time to censure your majesty's actions, and that in their old-school terms. They say you have lost the fairest game at Maw that ever king had, for want of making the best advantage of the five-finger, and playing the other helps in time. That your own card-holders play booty, and give the sign out of your own hand.' This gives us a suspicion of what the game of Maw was like, which is fully verified by the following verses under a caricature of the period, representing the kings of England, Denmark, and Sweden, with Bethlem Gabor, playing at cards against the pope and some monks. Denmark, not sitting far, and seeing what hand Great Britain had, and how Rome's loss did stand, Hope; to win something too: Maw is the game At which he plays, and challengeth at the same A Monk, who stakes a chalice; Denmark sets gold And shuffles; the Monk cuts; Denmark being bold, Deals freely round; and the first card he shews Is the five-fingers, which, being turned up, goes Cold to the Monk's heart; the next Denmark sees Is the ace of hearts; the Monk cries out I lees! Denmark replies, Sir Monk shew what you have; The Monk could shew him nothing but the knave. From the preceding allusions to the five-fingers (the five of trumps), the ace of hearts, and the knave, it is evident that Maw differed very slightly from Five Cards, the most popular game in Ireland at the present day. As early as 1674, this game was popular in Ireland, as we learn from Cotton's Compleat Gamester, which says: 'Five Cards is an Irish game, and is much played in that kingdom, for considerable sums of money, as All-fours is played in Kent, and Post-and-pair in the west of England.' Games migrate and acquire new names, as well as other things. Post-and-pair, formerly the great game of the west of England, has gone further west, and is now the Poker of the south-western states of America; and the American backwoodsman, when playing his favourite game of Euker, little thinks that he is engaged at the fashionable Parisian Ecarte. Noddy was one of the old English court games, and is thus noticed by Sir John Harrington: Now Noddy followed next, as well it might, Although it should have gone before of right; At which I say, I name not any body, One never had the knave, yet laid for Noddy. This has been supposed to have been a children's game, and it was certainly nothing of the kind. Its nature is thus fully described in a curious satirical poem, entitled Batt upon Batt, published in 1694. Shew me a man can turn up Noddy still, And deal himself three fives too, when he will; Conclude with one-and-thirty, and a pair, Never fail ten in Stock, and yet play fair, If Batt be not that Wight, I lose my aim. From these lines, there can be no doubt that the ancient Noddy was the modern Cribbage-the Nob of to-day, rejoicing in the name of Noddy, and the modern Crib, being termed the Stock. Cribbage is, in all probability, the most popular English game at cards at the present day. It seems as if redolent of English comfort, a snug fireside, a Welsh-rabbit, and a little mulled some-thing simmering on the hob. The rival powers of chance and skill are so happily blended, that while the influence of fortune is recognised as a source of pleasing excitement, the game of Cribbage admits, at the same time, of such an exertion of the mental faculties, as is sufficient to interest without fatiguing the player. It is the only game, known to the writer, that still induces the village surgeon, the parish curate, and two other old-fashioned friends, to meet occasionally, on a winter's evening, at the village inn. Ombre was most probably introduced into this country by Catherine of Portugal, the queen of Charles II; Waller, the court-poet, has a poem on a card torn at Ombre by the queen. This royal lady also introduced to the English court the reprehensible practice of playing cards on Sunday. Pepys, in 1667, writes: 'This evening, going to the queen's side to see the ladies, I did find the queen, the Duchess of York, and another at cards, with the room full of ladies and great men; which I was amazed at to see on a Sunday, having not believed, but contrarily flatly denied the same, a little while since, to my cousin.' In a passage from Evelyn's Memoirs, already quoted, the writer impressively describes another Sunday-evening scene at White-hall, a few days before the death of Charles II., in which a profligate assemblage of courtiers is represented as deeply engaged in the game of Basset. This was an Italian game, brought by Cardinal Mazarin to France; Louis XIV is said to have lost large sums at it; and it was most likely brought to England by some of the French ladies of the court. It did not stand its ground, however, in this country; Ombre continuing the fashionable game in England, down till after the expiration of the first quarter of the last century. It is utterly forgotten now, but being Belinda's game in the Rape of the Lock, where every incident in the deal is minutely described, it could be at once revived from that delightful poem. Pope's Grotto and Hampton Court excited in Miss Mitford's mind 'vivid images of the fair Belinda and the game of Ombre.' The writer, who resides in that classic neighbourhood, sometimes sees at auctions in old houses, the company puzzling their brains over a curious three-cornered table, wondering what it possibly could have been made for. It is an Ombre-table, expressly used for playing this game, and is represented, with an exalted party so engaged, on the frontispiece of Seymour's Compleat Gamester, published in 1739. From the title-page we learn that this work was written 'for the use of the young princesses.' These were the daughters of George, Prince of Wales, afterwards George II. One of them, Amelia, in her old-maidenhood, was a regular visitor at Bath, seeking health in the pump-room, and amusement at the card-table. Quadrille succeeded Ombre, but for a curious reason did not reign so long as its predecessor. From the peculiar nature of Quadrille, an unfair confederacy might be readily established, by any two persons, by which the other players could be cheated. In an annual publication, the Annals of Gaining, for 1775, the author says, 'this game is most commonly played by ladies, who favour one another by making signs. The great stroke the ladies attempt is keeping the pool, when by a very easy legerdemain they can serve themselves as many fish as they please.' While the preceding games were in vogue, the magnificent temple of Whist, destined to outshine and overshadow them, was in course of erection. Let India vaunt her children's vast address, Who first contrived the warlike sport of Chess; Let nice Piquette the boast of France remain And studious Ombre be the pride of Spain; Invention's praise shall England yield to none, When she can call delightful Whist her own. All great inventions and discoveries are works of time, and Whist is no exception to the rule; it did not come into the world perfect at all points, as Minerva emerged from the head of Jupiter. Nor were its wonderful merits early recognized. Under the vulgar appellations of Whisk and Swobbers, it long lingered in the servants-hall, ere it could ascend to the drawing room. At length, some gentlemen, who met at the Crown coffee-house, in Bedford Row, studied the game, gave it rules, established its principles, and then Edward Hoyle, in 1743, blazoned forth its fame to all the world. Whilst Ombre and Quadrille at court were used, And Basset's power the city dames amused, Imperial Whist was yet but light esteemed, And pastime fit for none but rustics deemed. How slow, at first, is still the growth of fame And what obstructions wait each rising name! Our stupid fathers thus neglected, long, The glorious boast of Milton's epic song; But Milton's muse, at last, a critic found, Who spread his praise o'er all the world around; And Hoyle, at length, for Whist performed the same, And proved its right to universal fame. Many attempts have been made, at various times, to turn playing-cards to a very different use from that for which they were originally intended. Thus, in 1518, a learned Franciscan friar, named Murner, published a Logica Memorativa, a mode of teaching logic, by a pack of cards; and, subsequently, he attempted to teach a summary of civil law in the same manner. In 1656, an Englishman, named Jackson, published a work, entitled the Seholar's Sciential Cards, in which he proposed to teach reading, spelling, grammar, writing, and arithmetic, with various arts and sciences, by playing cards; premising that the learner was well grounded in all the games played at the period. And later still, about the close of the seventeenth century, there was published the Genteel Housekeeper's Pastime; or the Mode of Carving at Table represented in a Pack of Playing-Cards, by which any one of Ordinary Capacity may learn how to Carve, in Mode, all the most 'usual Dishes of Flesh, Fish, Fowl, and Baked Meats, with the several Sauces and Garnishes proper to every Dish of Meat. In this system, flesh was represented by hearts, fish by clubs, fowl by diamonds, and baked-meat by spades. The king of hearts ruled a noble sirloin of roast-beef; the monarch of clubs presided over a pickled herring; and the king of diamonds reared his battle-axe over a turkey; while his brother of spades smiled benignantly on a well-baked venison-pasty. A still more practical use of playing-cards can be vouched for by the writer. Some years ago, a shrewd Yankee skipper, bound for New York, found himself contending against the long westerly gales of winter with a short and inefficient crew, but a number of sturdy Irish emigrants as passengers. It was most desirable to make the latter useful in working the ship, by pulling and hauling about the deck; but their utter ignorance of the names and positions of the various ropes rendered the project, at first sight, apparently impossible. The problem, however, was readily solved by placing a playing card, as a mark or tally, at each of the principal ropes; the red cards in the fore-part of the ship, the black cards in the after; hearts and clubs on the starboard-side, spades and diamonds on the larboard. In five minutes, every Irishman knew his station, and the position of the cards; there was no mysterious nautical nomenclature of tacks, sheets, halliards, braces, bowlines, &c., to bother the Hibernian mind. The men who were stationed at the ace of spades, for instance, well knew their post, and when called to tack ship, were always found at it; when orders were given to haul down the king of clubs, the rope was at once seized by ready hands. The writer has seen the after-guard and waisters of a newly-commissioned crack ship-of-war, longer in learning their stations, and becoming efficient in their duties, than those card-taught Irishmen were. Even the pulpit has not disdained to turn playing cards to practical use. Bishop Latimer, preaching at Cambridge on the Sunday before Christmas, 1527, suited his sermon to the card-playing practice of the season rather than the text. And Fuller gives another example of a clergyman preaching from Romans xii. 3-'As God hath dealt to every man the measure of faith.' The reverend gentleman in question adopted as an illustration of his discourse the metaphor of dealing as applied to cards, reminding his congregation that they should follow suit, ever play above-board, improve the gifts dealt out to them, take care of their trumps, play promptly when it became their turn, and so forth. The familiar name of the nine of diamonds has already been noticed in these pages. In Ireland, the six of hearts is still termed 'Grace's card.' The Honourable Colonel Richard Grace, an old Cavalier, when governor of Athlone for James II, was solicited, by promises of royal favour, to betray his trust, and espouse the cause of William III. Taking up a card, which happened to be the six of hearts, Grace wrote upon it the following reply, and handed it to the emissary who had been commissioned to make the proposal. 'Tell your master I despise his offer, and that honour and conscience are dearer to a gentleman, than all the wealth and titles a prince can bestow.' Short notes were frequently written on the back of playing-cards. In an old collection of poetry is found the following lines: TO A LADY, WHO SENT HER COMPLIMENTS TO A CLERGYMAN ON THE TEN OF HEARTS Your compliments, dear lady, pray forbear, Old. English services are more sincere; You send ten hearts the tithe is only mine, Give me but one, and burn the other nine. The kind of advertisements, now called circulars, were often, formerly, printed on the backs of playing-cards. Visiting cards, too, were improvised, by writing the name on the back of playing cards. About twenty years ago, when a house in Dean Street, Soho, was under repair, several visiting cards of this description were found behind a marble chimney-piece, one of them bearing the name of Isaac Newton. Cards of invitation were written in a similar manner. In the fourth picture, in Hogarth's series of 'Marriage-a-la-Mode', several are seen lying on the floor, upon one of which is inscribed: 'Count Basset begs to no how Lade Squander sleapt last niter Hogarth,' when he painted this inscription, was most probably thinking of Mrs. Centlivre's play, The Basset Table, which a critic describes as containing a great deal of plot and business, without much sentiment or delicacy. An animated description of a round game at cards, among a party of young people in a Scottish farmhouse, is given in Wilson's ever-memorable Nodes. It is the Shepherd who is represented speaking in this wise: 'As for young folks-lads and lasses, like-when the gudeman and his wife are gaen to bed, what 's the harm in a ggem at cairds? It's a chearfu', noisy, sicht o' comfort and confusion. Sic luckin' into anither's banns! Sic fause shufflin'! Sic unfair dealin'! Sic winkin' to tell your pairtner that ye hae the king or the ace! And when that wunna do, sic kickin' o' shins and treadin' on taes aneath the table-often the wrong anes! Then down wi' your haun' o' cairds in a clash on the boord, because you've ane ower few, and the coof maun lose his deal ! Then what gigglin' amang the lasses! What amicable, nay, love-quarrels, between pairtners! Jokin', and jeestin', and tauntin', and toozlin'-the cawnel blown out, and the soun' o' a thousan' kisses!-That's caird-playing in the kintra,Mr. North; and where's the manamang ye that wull dour to say that it's no a pleasant pastime o' a winter's nicht, when the snow is cumin' doon the lum, or the speat's rearm' amang the mirk mountains.' A curious and undoubtedly authentic historical anecdote is told of a pack of cards. Towards the end of the persecuting reign of Queen Mary, a commission was granted to a Dr. Cole to go over to Ireland, and commence a fiery crusade against the Protestants of that country. On coming to Chester, on his way, the doctor was waited on by the mayor, to whom he showed his commission, exclaiming, with premature triumph: 'Here is what shall lash the heretics of Ireland.' Mrs. Edmonds, the land-lady of the inn, having a brother in Dublin, was much disturbed by overhearing these words; so, when the doctor accompanied the mayor down stairs, she hastened into his room, opened his box, took out the commission, and put a pack of cards in its place. When the doctor returned to his apartment, he put the box into his portmanteau without suspicion, and the next morning sailed for Dublin. On his arrival, he waited on the lord-lieutenant and privy council, to whom he made a speech on the subject of his mission, and then presented the box to his lordship; but on opening it, there appeared only a pack of cards, with the knave of clubs uppermost. The doctor was petrified, and assured the council that he had had a commission, but what was become of it he could not tell. The lord-lieutenant answered: 'Let us have another commission, and, in the meanwhile, we can shuffle the cards.' Before the doctor could get his commission renewed, Queen Mary died, and thus the persecution was prevented. We are further informed that, when Queen Elizabeth was made acquainted with the circumstances, she settled a pension of £40 per annum on Mrs. Edmonds, for having saved her Protestant subjects in Ireland. There are few who it down to a quiet rubber that are aware of the possible combinations of the pack of fifty-two cards. As a curious fact, not found in Hoyle, it is worth recording here, that the possible combinations of a pack of cards cannot be numerically represented by less than forty-seven figures, arrayed in the following order: 16, 250, 563, 659, 176, 029, 962, 568, 164, 794, 000, 749, 006, 367, 006, 400. An old work on card-playing sums up the morality of the practice, very concisely, in the following lines: He who hopes at cards to win, Must never think that cheating's sin; To make a trick whene'er he can, No matter how, should he the plan. No case of conscience must he make, Except how he may save his stake; The only object of his prayers Not to be caught and kicked down stairs. A more summary process of ejectment, even, than kicking down stairs, seems to have been occasionally adopted in the olden time; sharpers having sometimes been thrown out of a window. A person so served at Bath, it is said, went to a solicitor for advice, when the following conversation took place: Says the lawyer: 'What motive for treatment so hard?' 'Dear sir, all my crime was but-slipping a card.' 'Indeed! For how much did you play then, and where!' 'For two hundred, up two pair of stairs at the Bear.' 'Why, then, my good friend, as you want my advice, Tether guinea advanced, it is yours in a trice.' 'Here it is, my dear sir.'-' Very well, now observe, Future downfalls to shun, from this rule never swerve, When challenged upstairs, luck for hundreds to try, Tell your frolicsome friends, that you don't play so high!' The card-player has had his epitaph. Let us conclude with it: His card is cut-long days he shuffled through The game of life-ho dealt as others do: Though he by honours tells not its amount. When the last trump is played, his tricks will count. |