26th FebruaryBorn: Anthony Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, 1671, Exeter house; Rev. James Hervey, author of Meditations, 1714, Hardingstone; Francois J. D. Arago, natural philosopher, 1786; Victor Hugo, fictitious writer, 1802. Died: Manfred (of Tarento), killed, 1266; Robert Fabian, chronicler, 1513, Cornhill; Sir Nicholas Crispe, Guinea trader, 1665, Hammersmith; Thomas D'Urfey, wit and poet, 1723, St. James's; Maximilian (of Bavaria), 1726, Munich; Joseph Tartine, musical composer, 1770, Padua; Dr. Alexander Geddes, theologian, 1802, Paddington; John Philip Kemble, actor, 1823, Lausanne; Dr. William Kitchiner, littérateur, 1827, St. Pancras; Sir William Allan, R.A., painter, 1850; Thomas Moore, lyric poet, 1852; Thomas Tooke, author of the History of Prices, &c., 1858, London. Feast Day: St. Alexander, patriarch of Alexandria, 326. St. Parphyrius, bishop of Gaza, 420. St. Victor, of Champagne, 7th century. ECCENTRICITIES OF DR. WILLIAM KITCHINER

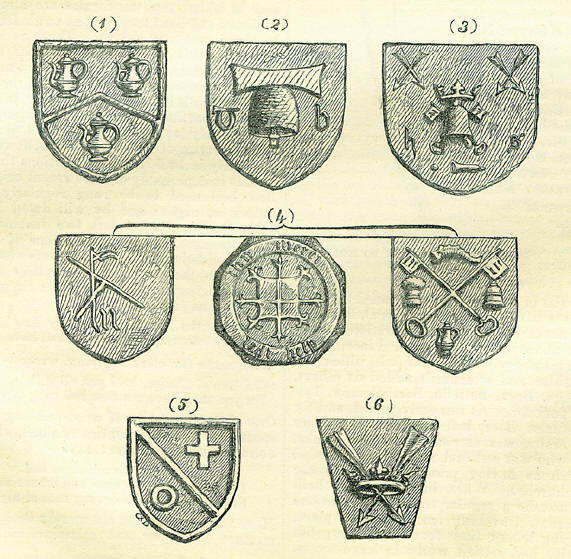

Eccentricity in cookery-books is by no means peculiar to our time. We have all read of the oddities of Mrs. Glasse's instructions; and most olden cookery-books savour of such humour, not to mention as oddities the receipts for doing out-of-the-way things, such as 'How to Roast a Pound of Butter,' which we find in the Art of Cookery, by a lady, 1748. To the humour of Dr. Kitchiner in this way we doubtless owe a very good book -his Cook's Oracle, in which the instructions are given with so much come-and-read-me pleasantry and gossiping anecdote as to win the dullest reader. But Kitchiner was not a mere book-making cook: he practised what he taught, and he had ample means for the purpose. From his father, a coal-merchant in an extensive way of business in the Strand, he had inherited a fortune of £60,000 or £70,000, which was more than sufficient to enable him to work out his ideal of life. His heart overflowed with benevolence and good humour, and no man better understood the art of making his friends happy. He shewed equal tact in his books: his Cook's Oracle is full of common-sense practice; and lest his reader should stray into excess, he wrote The Art of Invigorating and Prolonging Life, and a more useful book in times when railways were not - The Traveller's Oracle, and Horse and Carriage Keeper's Guide. With his ample fortune, Kitchiner was still an economist, and wrote a Housekeeper's Ledger, and a coaxing volume entitled The Pleasures of Making a Will. He also wrote on astronomy, telescopes, and spectacles. In music he was a proficient: and in 1820, at the coronation of George IV, he published a collection of the National Songs of Great Britain, a folio volume, with a splendid dedication plate to His Majesty. Next he edited The Sea Songs of Charles Dibdin. But, merrily and wisely as Kitchiner professed to live, he had scarcely reached his fiftieth year when he was taken from the circle of friends. At this time he resided at No. 43, Warren-street, Fitzroy-square. On the 26th of February he joined a large dinner-party given by Mr. Braham, the celebrated singer: he had been in high spirits, and had enjoyed the company to a later hour than his usually early habits allowed. Mathews was present, and rehearsed a portion of a new comic entertainment, which induced Kitchiner to amuse the party with some of his whimsical reasons for inventing odd things, and giving them odd names. He returned home, was suddenly taken ill, and in an hour he was no more! Though always an epicure, and fond of experiments in cookery, and exceedingly particular in the choice of his viands, and in their mode of preparation for the table, Kitchiner was regular, and even abstemious, in his general habits. His dinners were cooked according to his own method: he dined at five: supper was served at half-past nine: and at eleven he retired. Every Tuesday evening he gave a conversazione, at which he delighted to bring together professors and amateurs of the sciences and the polite arts. For the regulation of the party the Doctor had a placard over his drawing-room chimney-piece, inscribed 'Come at seven, go at eleven.' It is said that George Colman the younger, being introduced to Kitchiner on one of his evenings, and reading this admonition, found an opportunity to insert in the placard after 'go' the pronoun 'it,' which, it must be admitted, materially altered the reading. In these social meetings, when the Doctor's servant gave the signal for supper, those who objected to take other than tea or coffee departed; and those who remained descended to the dining-room, to partake of his friendly fare. A cold joint, a lobster salad, and some little entremets, usually formed the summer repast: in winter some nicely, cooked hot dishes were set upon the board, with wine, liqueurs, and ales from a well-stocked cellar. Such were the orderly habits at these evening parties, that, 'on the stroke of eleven,' hats, umbrellas, &c., were brought in, and the Doctor attended his guests to the street-door, where, first looking at the stars, he would give them a cordial shake of the hand, and a hearty 'good night,' as they severally departed. Kitchiner's public dinners, as they may be termed, were things of more pomp, ceremony, and etiquette: they were announced by notes of invitation, as follows: 'Dear Sir,-The honour of your company is requested, to dine with the Committee of Taste, on Wednesday next, the 10th instant. The specimens will be placed on the table at five o'clock precisely, when the business of the day will immediately commence. I have the honour to be Your most obedient Servant, W. Kitchiner, Sec. 'August, 1825, 43, Warren-street, Fitzroy-square. At the last general meeting, it was unanimously resolved-that '1st. An invitation to ETA BETA PI must be answered in writing, as soon as possible after it is received-within twenty-four possible at latest, -reckoning from that at which, it was dated: otherwise the secretary will have the profound regret to feel that the invitation has been definitely declined. 2nd. The secretary having represented that the perfection of the several preparations is so exquisitely evanescent that the delay of one minute, after the arrival at the meridian of concoction, will render them no longer worthy of men of taste : Therefore, to ensure the punctual attendance of those illustrious gastrophilists who, on this occasion, are invited to join this high tribunal of taste-for their own pleasure, and the benefit of their country-it is irrevocably resolved-' That the janitor be ordered not to admit any visitor, of whatever eminence of appetite, after the hour at which the secretary shall have announced that the specimens are ready.' By Order of the Committee, W. Kitchiner, Sec.' At the last party given by the Doctor on the 20th February, as the first three that were bidden entered his drawing-room, he received them seated at his grand pianoforte, with 'See the Conquering Hero comes!' accompanying the air by placing his feet on the pedals, with a peal on the kettle-drums beneath the instrument. Alas, the conquering hero was not far off! The accompanying whole-length portrait of Dr. Kitchiner has been engraved from a well-executed mezzotint-a private plate -'painted and engraved by C. Turner, engraver in ordinary to His Majesty.' The skin of the stuffed tiger on the floor of the room was brought from Africa by Major Denham, and presented by him to his friend Kitchiner. SUSPENSION OF CASH PAYMENTS IN 1797In the great war which England commenced against France in 1793, the first four years saw two hundred millions added to the national debt, without any material advantage being gained: on the contrary, France had become more formidable than at first, had made great acquisitions, and was now less disposed to peace than ever. So much coin had left the country for the payment of troops abroad, and as subsidies to allies, that the Bank during 1796 began to feel a difficulty in satisfying the demands made upon it. At the close of the year, the people began to hoard coin, and to make a run upon the country banks. These applied to the Bank of England for help, and the consequence was, that a run upon it commenced in the latter part of February 1797. This great establishment could only keep itself afloat by paying in sixpences. Notwithstanding the sound state of its ultimate resources, its immediate insolvency was expected,-an event the consequences of which must have been dreadful. In that exigency, the Government stepped in with an order in council (February 26), authorizing the notes of the bank as a legal tender, until such time as proper remedies could be provided. This suspension of cash payments by the Bank of England-a virtual insolvency-was attended by the usual effect of raising the nominal prices of all articles: and, of course, it deranged reckonings between creditors and debtors. It was believed, however, to be an absolutely indispensable step, and the Conservative party always regarded it as the salvation of the country. A return to cash payments was from the first promised and expected to take place in a few months: but, as is well known, King Paper reigned for twenty-two years. During most of that time, a guinea bought twenty-seven shillings worth of articles. It was just one of the dire features of the case that even a return to what should never have been departed from, could not be effected without a new evil: for of course, whereas creditors were in the first instance put to a disadvantage, debtors were so now. The public debt was considered as enhanced a third by the act of Sir Robert Peel for the resumption of cash payments, and all private obligations rose in the same proportion. On a review of English history during the last few years of the eighteenth century, one gets an idea that there was little sound judgment and much recklessness in the conduct of public affairs: but the spirit of the people was unconquerable, and to that a very poor set of administrators were indebted for eventual successes which they did not deserve. In the council-chamber of the Guildhall, Norwich, is a glass case containing a sword, along with a letter spewing how the weapon came there. When, in the midst of unexampled national distress, and an almost general mutiny of the sailors, the English fleet under Sir John Jervis engaged and beat the much superior fleet of Spain off Cape St. Vincent, February 14, 1797, Captain Nelson, in his ship the Captain, seventy-four, disabled several vessels, and received the surrender of one, the San Josef, from its commander, after having boarded it. [This unfortunate officer soon after died of his wounds.] It would appear that, a few days after the action, Nelson bethought him of a proper place to which to assign the keeping of the sword of the Spanish commander, and he determined on sending it to the chief town of his native county. This symbol of victory accordingly came to the Mayor of Norwich, accompanied by a letter which is here exactly transcribed: Irresistible, off Lisbon, Feb. 26th, 1797 Sir, Having the good for-tune on the most glorious 14th February to become possessed of the sword of the Spanish Rear Admiral Don Xavier Francesco Wintheysen in the way sett forth in the paper transmitted herewith. And being Born in the County of Norfolk, I beg leave to present the sword to the City of Norwich in order to its being preserved as a memento of this event, and of my affection for my native County. I have the honor to Be, Sir, your most Obedient servant, Horatio Nelson To the Mayor of Norwich. CHURCH BELLSLarge bells in England are mentioned by Bede as early as A.D. 670. A complete peal, however, does not occur till nearly 200 years later, when Turketul, abbot of Croyland, in Lincolnshire, presented his abbey with a great bell, which was called Guthlac, and afterwards added six others, named Pega, Bega, Bettelin, Bartholomew, Tatwin, and Turketul. At this early period, and for some centuries later, bell-founding, like other scientific crafts, was carried on by the monks. Dunstan, who was a skilful artificer, is recorded by Ingulph as having presented bells to the western churches. When in after times bell-founding became a regular trade, some founders were itinerant, travelling from place to place, and stopping where they found business: but the majority had settled works in large towns. Among other places London, Gloucester, Salisbury, Bury St. Edmunds, Norwich, and Colchester have been the seats of eminent foundries. Bells were anciently consecrated, before they were raised to their places, each being dedicated to some divine personage, saint, or martyr. The ringing of such bells was considered efficacious in dispersing storms, and evil spirits were supposed to be unable to endure their sound. Hence the custom of ringing the 'passing bell' when any one was in articulo mortis, in order to scare away fiends who might otherwise molest the departing spirit, and also to secure the prayers of such pious folk as might chance to be within hearing. An old woman once related to the writer, how, after the death of a wicked squire, his spirit came and sat upon the bell, so that all the ringers together could not toll it. The bell-cots, so common on the gable-ends of our old churches, in former times contained each a 'Sancte' bell, so called from its being rung at the elevation of the host: one may be seen, still hanging in its place, at Over, Cambridgeshire. It is scarcely probable that any bells now remain in this country of date prior to the 14th or at most the 13th century, and of the most ancient of these the age can only be ascertained approximately, the custom of inserting the date in the inscription (which each bell almost invariably bears) not having obtained until late in the 16th century. The very old bells expand more gradually from crown to rim than the modern ones, which splay out somewhat abruptly towards the mouth. It may be added that the former are almost invariably of excellent tone, and as a rule far superior to those cast now-a-days. There is a popular idea that this is in consequence of the older founders adding silver to their bell-metal: but recent experiments have shewn that the presence of silver spoils instead of improving the tone, in direct proportion to the quantity employed. A cockney is usually defined as a person born within hearing of Bow bells: Stow, however, who died early in 1605, nowhere mentions this notion, so that it is probably of more recent origin. The Bow bell used to be rung regularly at nine o'clock at night: and by will dated 1472, one John Donne, Mercer, left two tenements with appurtenances, to the maintenance of Bow bell. 'This bell being usually rung somewhat late, as seemed to the young men 'prentices and other in Cheape, they made and set up a rhyme against the clerk, as followeth: Clarke of the Bow bell with the yellow locks, For thy late ringing thy head shall have knocks.' Whereunto the clerk replying, wrote Children of Cheape, hold you all still, For you shall have the Bow bell rung at your will. One of the finest bits of word-painting in Shakspeare occurs in the mention of a bell, where King John, addressing Hubert, says: If the midnight bell Did with his iron tongue and brazen mouth Sound one unto the drowsy race of night. Here 'brazen' implies not merely that particular mixture of copper and calamine, called brass, but in a broader sense, any metal which is compounded with copper. This acceptation of the term is noticed by Johnson, and in confirmation occurs the fact that the name of Brasyer was borne of old by an eminent family of east-country bell-founders; being, like Bowyer, Miller, Webber, &c. &c., a trade-name, i.e. derived from the occupation of the bearer. The inscriptions on the oldest bells are in the Lombardic and black-letter characters, the former probably the more ancient; the black-letter was superseded by the ordinary Roman capitals, towards the close of the sixteenth century. Even later, however, than this, some founders employed a sort of imitation of the old Lombardic. The commonest black-letter inscription is a simple invocation, as 'Ave Maria,' or 'Sancte, ora pro nobis.' After the Reformation these invocations of course disappeared, and founders then more frequently placed their names on the bells, with usually some rhyme or sentiment, which, as some of the following specimens will prove, is often sad doggrel: 'Hethatwilpvrchashonorsgaynemvstancientlathers [sic] stillmayntayne.' Four bells at Graveley, Cambridgeshire, are thus inscribed  The older founders, as we have seen, seldom placed their names on their bells: yet the black-letter and later Lombardic inscriptions are often accompanied by their Foundry-stamps, or trade marks, some specimens of which are engraved above: (1) Occurs on two bells at Brent-Tor, Devon, and elsewhere: the three vessels so like coffee-pots are founders' lave-pots. (2) Is supposed to be the stamp of a London foundry: it may be seen on four bells at St. Bartholomew's, Smithfield. (3) Is the stamp of a Bury St. Edmund's foundry: the gun and bullet indicate that H. S. was also a gun-founder. (6) Is the mark of Stephen Tonni, who founded at Bury about 1570. The crown and arrows are typical of the martyrdom of St. Edmund. During the Civil War, many church bells were melted down and cast into cannon. Not quite so honourable was the end of four large bells which once hung in a clockier or clock-tower in St. Paul's Cathedral, which tower was pulled down by Sir Miles Partridge in the reign of Henry VIII, and the common speech then was that 'he did set a hundred pounds upon a cast of dice against it, and so won the said clockier and bells of the King, and then causing the bells to be broken as they hung, the rest was pulled down.' THE SILENT TOWER OF BOTTREAUXThe church at Boscastle, in Cornwall, has no bells, while the neighbouring tower of Tintagel contains a fine peal of six: it is said that a peal of bells for Boscastle was once cast at a foundry on the Continent, and that the vessel which was bringing them went down within sight of the church tower. The Cornish folk have a legend on this subject, which has been embodied in the following stanzas by Mr. Hawker: Tintagel bells ring o'er the tide, The boy leans on his vessel's side, He hears that sound, and dreams of home Soothe the wild orphan of the foam. Come to thy God in time,' Thus saith their pealing chime: 'Youth, manhood, old age past, Come to thy God at last.' But why are Bottreaux's echoes still? Her tower stands proudly on the hill, Yet the strange though that home hath found, The lamb lies sleeping on the ground. 'Come to thy God in time,' Should be her answering chime: Come to thy God at last,' Should echo on the blast. The ship rode down with courses free, The daughter of a distant sea, Her sheet was loose, her anchor stored, The merry Bottreaux bells on board. 'Come to thy God in time,' Rung out Tintagel chime: 'Youth, manhood, old age past, Come to thy God at last.' The pilot heard his native bells Hang on the breeze in fitful spells. 'Thank God,' with reverent brow, he cried, 'We make the shore with evening's tide.' Come to thy God in time,' It was his marriage chime: Youth, manhood, old age past, Come to thy God at last.' Thank God, thou whining knave, on land, But thank at sea the steersman's hand,' The captain's voice above the gale, Thank the good ship and ready sail.' 'Come to thy God in time,' Sad grew the boding chime: 'Come to thy God at last,' Boomed heavy on the blast. Up rose that sea, as if it heard The Mighty Master's signal word. What thrills the captain's whitening lip? The death-groans of his sinking ship. 'Come to thy God in time,' Swung deep the funeral chime, 'Grace, mercy, kindness, past Come to thy God at last.' Long did the rescued pilot tell, When grey hairs o'er his forehead fell, While those around would hear and weep, That fearful judgment of the deep. 'Come to thy God in time,' He read his native chime: 'Youth, manhood, old age past, Come to thy God at last.' Still, when the storm of Bottreaux's waves Is waking in his weedy caves, Those bells, that sullen surges hide, Peal their deep tones beneath the tide. 'Come to thy God in time,' Thus saith the ocean chime; Storm, whirlwind, billow past, Come to thy God at last.' THE ROOKS AND NEW STYLEThe 26th of February, N. S., corresponds to the day which used to be assigned for the rooks beginning to search for materials for their nests, namely, the twelfth day after Candlemas, 0. S. The Rev. Dr. Waugh used to relate that, on his return from the first year's session at the University of Edinburgh, his father's gardener undertook to give him a few lessons in natural history. Among other things, he told him that the 'craws' (rooks) always began building twelve days after Candlemas. Wishful to shew off his learning, young Waugh asked the old man if the craws counted by the old or by the new style, just then introduced by Act of Parliament. Turning upon the young student a look of contempt, the old gardener said-'Young man, craws care nothing for acts of parliament.' |