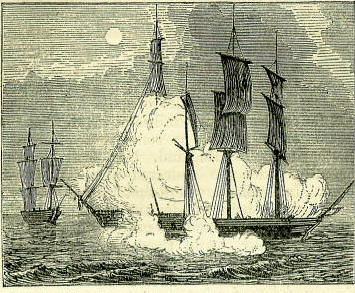

23rd SeptemberBorn: Octavius Caesar Augustus, first Roman emperor, 63 B.C., Aricia; Dr. Jeremy Collier, celebrated author of A View of the Stage, &c., 1650, Stow Qui, Cambridge-shire; Karl Theodor Körner, German poet, 1791, Dresden. Died: Bishop Jewel, eminent prelate,1571; Herman Boerhaave, distinguished physician, 1738, Leyden; Dr. Matthew Baillie, eminent physician, 1823; William Upcott, collector of historical manuscripts, 1845, London; Edward Wedlake Brayley, topographical and antiquarian writer, 1854. Feast Day: St. Linus, pope and martyr, 1st century. St. Thecla, virgin and martyr, 1st century. St. Adamnan, abbot, 705. KARL THEODOR KÖRNERThe life-blood of Germany was never roused nor quickened with greater impetus, than when the old fatherland sprung to arms to assert its rights against the tyrannical sway of France, towards the close of the first Napoleon's career. For years she had groaned under the sway; but repeated defeats had taught her to succumb to the oppression which it seemed impossible to resist. Hope at last gleamed upon her from the lights of burning Moscow, and in 1813 she rose, determined to throw off the yoke. In thus vindicating her outraged rights, she was nobly supported by the intellect and genius, as well as military prowess of her sons. The stirring lectures of Fichte, and the martial lyrics of Körner, were no less effective towards the liberation of their country than the valour and strategical skill of Lützow and Blucher. The father of Karl Theodor Körner held a distinguished position as member of the privy-council of Saxony, and numbered Goethe and Schiller among his personal friends. In his infantine days, Karl was a sickly delicate child, but as he advanced in years, he rapidly outgrew all these signs of weakness, and by the time he approached manhood, was noted for his adroitness in all manly exercises, more especially horsemanship and fencing, besides being renowned for his musical skill, and grace and. agility as a dancer. To crown all these, nature had bestowed on him a fine military figure and handsome countenance, with large, full, and expressive eyes. The law was the profession to which his father's wishes would have destined him; but young Köner's tastes inclining more to natural science and engineering, he was sent, when a stripling, to Freiberg, to study mining in the school there presided over by the celebrated geologist, Werner. He pursued his studies in this place in theoretical and practical mining with much enthusiasm, but quitted it in 1810, to attend the university of Leipsic, from which, after remaining for a short time, he proceeded to that of Berlin. In the same year, he made his first appearance before the public, by the issue of a small volume of poems, entitled Die Knospen, or 'The Buds.' From Berlin he was sent by his father to Vienna, where he seems to have turned his attention chiefly to dramatic composition, and produced several pieces, one of which, more especially, a tragedy on the subject of Zriny, the Hungarian hero, was per-formed with immense success. Among his friends in Vienna were included Wilhelm von Humboldt, then ambassador from the Prussian court, and Frederick Schlegel, the celebrated historical commentator and poet. During his stay in Vienna, also, he formed an ardent attachment to a young lady, which met the entire approbation of his family, and arrangements were entered into for their speedy union. But another bride now claimed the attentions of Körner. The cry to arms which in the spring of 1813 echoed from one end of Germany to the other, found an enthusiastic response in his bosom, and he felt himself impelled to take his place forth-with in the ranks of those patriots who were striving for the liberation of their country in Prussia and the northern states of the confederation. Writing to his father, he says: 'Germany is roused; the Prussian eagle flaps its wings and awakes in all true hearts the great hope of German freedom. My genius sighs for its fatherland; let me be its worthy son. Now that I know what happiness may be realised in this life, and when all the stars of my destiny look down on me with such genial rays, now does a righteous inspiration tell me that no sacrifice can be too great for that highest of all human blessings, the vindication of a nation's freedom.' In pursuance of this resolve, Körner, in the month of March, quitted Vienna, and proceeded to Breslau, where he joined Lützow's celebrated company of volunteers, or the Black Huntsmen, as they were termed. A few days after his joining the corps, it was solemnly dedicated to the service of its country in the church of Rochau, the services concluding with Luther's noble hymn, Bin fester Burg ist unser Gott. The powers of physical endurance which Körner had acquired in the course of his mining studies at Freiberg, proved of eminent service to him in the fatigues of a military life. His enthusiasm and aptitude for his new duties soon procured his elevation to the post of lieutenant, whilst the geniality and kindliness of his nature made him the idol of his comrades. Here, too, his martial muse was fairly called into action, and some of the noblest of those lyrics which have rendered him the Tyrtaeus and Pindar of Germany, were composed beside the bivouac and watch-fires during the intervals of military duty. In the battle of Gorde, near the Elbe, where the French received a signal check, and in the subsequent victorious march of Lützow's volunteers by Halberstadt and Eisleben to Plauen, Körner took a prominent part, acting in the latter movement as adjutant to the commander. Whilst lying at Plauen, an intimation was treacherously conveyed to Lützow of an armistice having been concluded, and he accordingly proceeded to Kitzen, a village in the neighbourhood of Leipsic. Here he found himself surrounded and threatened by a large body of French, and Körner was despatched to demand an explanation from the officer in command, who, instead of replying, cut him down with his sword, and a general engagement ensued. The Black Huntsmen were forced to save themselves by flight; and Körner, who had only escaped death by his horse swerving aside, took shelter in a neighbouring wood, where he was nearly being discovered by a detachment of French, but contrived to scare them away by shouting in as stentorian tones as he could utter: ' The fourth squadron will advance!' Faint with the loss of blood, and the stunning effects of a severe wound in the head, he at length fell in with some of his old comrades, who procured him surgical assistance, and he managed afterwards to get himself smuggled into Leipsic, then under the rigorous military rule of the French. From this he escaped to Karlsbad, and at last, after visiting various places, reached Berlin, where he succeeded in completely re-establishing his health. Anxious to join again his companions in arms, he now hurried back to the banks of the Elbe, where Marshal Davoust, with a strong reinforcement of Danish troops from Hamburg, was threatening Northern Germany. On 17th August, hostilities were renewed, and Lützow's troops, who guarded the outposts, were brought almost daily into contact with the enemy. On the 25th, the commander resolved to make an attack with a detachment of his cavalry on the rear of the French, but in the meantime received intelligence of an approaching convoy of provisions and military stores escorted by two companies of infantry. This transport had to pass a wood at a little distance from Rosenberg, and here Lützow posted his men, disposing them in two divisions, one of which, with himself at their head, should attack the enemy on the flank, whilst the other remained closed up to cover the rear. During their halt in the thicket, Körner, who acted as Lützow's adjutant, employed the interval of leisure in composing his celebrated Sword-Song, which was found in his pocket-book after his death, and has not inaptly been likened to the lay of the dying swan. On the enemy's detachment coming up, it proved stronger than had been anticipated, but it nevertheless broke and fled before the Prussian cavalry, who pursued them across the plain to a thicket of underwood. Here a number of their sharp-shooters ensconced themselves, and for a time galled Lützow's troops by a shower of bullets. One of these passed through the neck of Körner's horse, and afterwards the abdomen and backbone of his rider, who fell mortally wounded. He was conveyed at once by his comrades to a quiet spot in the wood, and assistance was procured, but the never regained consciousness after receiving the wound, and in a few minutes expired. He had met the death which of all others he had vaunted in his lyrics as the most to be desired-that of a soldier in the arms of victory, and in defence of the liberties of his country. This event took place in the gray dawn of an autumn morning, on the 26th August 1813. His body was interred, with all the honours of war, beneath an oak on the roadside near the village of Wobbelin. The tomb has since been surrounded by a wall and a monument erected to his memory, the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin making a present of the ground to Körner's family. Here, a few years later, were deposited the remains of Theodor's beloved sister, Emma, and, at a subsequent period, those of his father. Thus prematurely terminated, at the age of twenty-two, the career of this young hero whose patriotic lyrics, like those of Moritz Arndt, seem to have entwined themselves round the very heart-strings of the German people. Though somewhat inferior in sonorous majesty to Thomas Campbell's warlike odes, they possess a superiority over them in point of the earnestness with which every lineof the German poet is animated. Young, brave, and generous, his effusions are literally the out-breathings of an unselfish and gallant spirit, which disregards every danger, and counts all other considerations as dross in the attainment of some grand and noble end. A collection of his martial poems, under the title of Leyer und Schwerdt (Lyre and Sword), was published at Berlin the year following his death. Many of these, including 'My Father-land,' The Song of the Black Huntsmen,' Lutzow's Wild Chase,' `The Battle-prayer,' and `The Sword Song' are well known to the English public through translations. One of Körner's most popular songs, is ' The Song of the Sword,' which he wrote only two hours before the engagement in which he was shot. He compares his sword to a bride, and represents it as pleading with him to consummate the wedding. This explains the allusion in the following poem by Mrs. Hemans, which we quote as a graceful tribute from one of ourselves to the memory of a noble stranger. FOR THE DEATH-DAY OF THEODOR KÖRNER. A song for the death-day of the brave, A song of pride! The youth went down to a hero's grave, With the sword, his bride! He went with his noble heart unworn, And pure, and high; An eagle stooping from clouds of morn, Only to die. He went with the lyre, whose lofty tone, Beneath his hand, Had thrill'd to the name of his God alone, And his fatherland. And with all his glorious feelings yet In their day-spring's glow, Like a southern stream that no frost bath met To chain its flow! A song for the death-day of the brave, A song of pride! For him that went to a hero's grave With the sword, his bride! He has left a voice in his trumpet lays To turn the fight; And a spirit to shine through the after-days As a watch-fire's light; And a grief in his father's soul to rest ' Midst all high thought; And a memory unto his mother's breast With healing fraught. And a name and fame above the blight Of earthly breath; Beautiful-beautiful and bright In life and death! A song for the death-day of the brave, A song of pride! For him that went to a hero's grave With the sword, his bride! UPCOTT, THE MANUSCRIPT-COLLECTORIn a work of this nature, it would be improper to omit reference to one so devoted to the collection and preservation of English historical curiosities as William Upcott, sometimes styled the King of Autograph-collectors. Ostensibly, he pursued a modest career in life, as under-librarian of the London Institution: the life below the surface exhibited him as acting under the influence of a singular instinct for the acquisition of documents connected with English history-one of those aids to literature whose names are generally seen only in foot-notes or in sentences of prefaces, while the truth is that, but for them, the efforts and the powers of the most accomplished historians would be vain. Upcott was born in Oxfordshire in 1779, and was set up originally as a collector by his god-father, Ozias Humphrey, the eminent portrait-painter, who left him his correspondence. With this as a nucleus, he went on collecting for a long series of years, till, in 1836, his collection consisted of thirty-two thousand letters illustrated by three thousand portraits, the value of the whole being estimated by himself at £10,000. That this was not an extravagant appraisement may now be averred, when we know that, after large portions of the collection had been disposed of; a mere remnant, sold by auction after the collector's death, brought £412, 17s. 6d. It was to Upcott that the public was indebted for the preservation of the manuscript of the Diary of John Evelyn, a valuable store of matter regarding English familiar life in the seventeenth century. The Correspondence of Henry, Earl of Clarendon, and that of Ralph Thoresby, were also published from the originals in Mr. Upcott's collection. This singular enthusiast spent the last years of his useful and unpretending life in an old mansion in the Upper Street at Islington, which he quaintly denominated Autograph Cottage. NAVAL ENGAGEMENT OFF FLAMBOROUGH HEAD, SEPTEMBER 23, 1779 On 23rd September 1779, a serious naval engagement took place on the coast of Yorkshire, H.M.S. Serapis and Countess of Scarborough being the ships on the one side, and a squadron under the command of the celebrated adventurer Paul Jones on the other. It was a time of embarrassment in England. Unexpected difficulties and disasters had been experienced in the attempt to enforce the loyalty of the American colonies. Several of England's continental neighbours were about to take advantage of her weakness to declare against her. In that crisis it was that Jones came and insulted the coasts of Britain. Driven out of the Firth of Forth by a strong westerly wind, he came south-wards till he reached the neighbourhood of Flamborough Head, where he resolved to await the Baltic and merchant fleet, expected shortly to arrive there on its homeward voyage under the convoy of the two men-of-war above mentioned. About two o'clock in the afternoon of the 23rd September, Jones, on board of his vessel the Bon Homme Richard (so called after his friend Benjamin Franklin), descried the fleet in question, with its escort, advancing north-north-east, and numbering forty-one sail. He at once hoisted the signal for a general chase, on perceiving which the two frigates bore out from the land in battle-array, whilst the merchant vessels crowded all sail towards shore, and succeeded in gaining shelter beneath the guns of Scarborough Castle. There was little wind, and, according to Jones's own account, it was nightfall before the Bon Honnne Richard could come up with the Serapis, when an engagement within pistol-shot commenced, and continued at that distance for nearly an hour, the advantage both in point of manageableness and number of guns being on the side of the British ship; whilst the remaining vessels of Jones's squadron, from some inexplicable cause, kept at a distance, and he was obliged for a long time to maintain single-handed a contest with the two English frigates. The harvest-moon, in the meantime, rose calm and beautiful, casting its silver light over the waters of the German Ocean, the surface of which, smooth as a mirror, bore the squadrons engaged in deadly conflict. Suddenly, some old eighteen-pounders on board the Bon Homme Richard exploded at their first discharge, killing and wounding many of Jones's sailors; and as he had now only two pieces of cannon on the quarter-deck remaining unsilenced, and his vessel had been struck by several shots below the water-level, his position was becoming very critical. Just then, while he ran great danger of going to the bottom, the bowsprit of the Serapis came athwart the poop of the Bon Homme Richard, and Jones, with his own hands, made the two vessels fast in that position. A dreadful scene at close-quarters then ensued, in which Captain Pearson, the British commander, inflicted signal damage by his artillery on the under part of his opponent's vessel, whilst his own decks were rendered almost untenable by the hand-grenades and volleys of musketry which, on their cannon becoming unserviceable, the combatants on board the Bon Homme Richard discharged with murderous effect. For a long time the latter seemed decidedly to have the worst of the contest, and on one occasion the master-gunner, believing that Jones and the lieutenant were killed, and himself left as the officer in command, rushed up to the poop to haul down the colours in the hopelessness of maintaining any longer the conflict. But the flagstaff had been shot away at the commencement of the engagement, and he could only make his intentions known by calling out over the ship's side for quarter. Captain Pearson then hailed to know if the Bon Homme Richard surrendered, an interrogation which Jones immediately answered in the negative, and the fight continued to rage. Meantime the Countess of Scarborough had been engaged by the Pallas, a vessel belonging to Jones's squadron, and after a short conflict had surrendered. The Bon Homme Richard-was thus freed from the attacks of a double foe, but was at the same time nearly brought to destruction by the Alliance, one of its companion-vessels, which, after keeping for a long time at a distance, advanced to the scene of action, and poured in several broadsides, most of which took effect on her own ally instead of the British frigate. At last the galling fire from the shrouds of Jones's ship told markedly in the thinning of the crew of the Serapis, and silencing her fire: and a terrible explosion on board of her, occasioned by a young sailor, a Scotchman, it is alleged, who, taking his stand upon the extreme end of the yard of the Bon Homme Richard, dropped a grenade on a row of cartridges on the main-deck of the Serapis, spread such disaster and confusion that Captain Pearson shortly afterwards struck his colours and surrendered. This was at eleven o'clock at night, after the engagement had lasted for upwards of four hours. The accounts of the losses on both sides are very contradictory, but seem to have been nearly equal, and may be estimated in all at about three hundred killed and wounded. The morning following the battle was extremely foggy, and on examining the Bon Homme Richard, she was found to have sustained such damage that it was impossible she could keep longer afloat. With all expedition her crew abandoned her, and went on board the Serapis, of which Paul Jones took the command. The Bon Homme Richard sank almost immediately, with a large sum of money belonging to Jones, and many valuable papers. The prize-ships were now conveyed by him to the Texel, a proceeding which led to a demand being made by the English ambassador at the Hague for the delivery of the captured vessels, and the surrender of Jones himself as a pirate. This application to the Dutch authorities was ineffectual, but it served as one of the predisposing causes of the war which not long afterwards ensued with England After remaining for a while at the Texel, the Serapis was taken to the port of L'Orient, in France, where she appears subsequently to have been disarmed. and broken up, whilst the Countess of Scarborough was conveyed to Dunkirk. Meantime, Jones proceeded to France, with the view of arranging as to his future movements; but before quitting Texel, he returned to Captain Pearson his sword, in recognition, as he says, of the bravery which he had displayed on board the Serapis. Pearson's countrymen seem to have entertained the same estimate of his merits, as, on his subsequent return to England, he was received with great distinction, was knighted by George III, and presented with a service of plate and the freedom of their corporations, by those boroughs on the east coast which lay near the scene of the naval engagement. In France, honours no less flattering were bestowed on Paul Jones. At the opera and all public places, he received enthusiastic ovations, and Louis XVI presented him with a gold-hilted sword, on which was engraved, 'Vindicati maris Ludovicus XVI. remunerator strenuo vindici' (From Louis XVI., in recognition of the services of the brave maintainer of the privileges of the sea). It may be noted that the true name of Paul Jones was John Paul, and that he made the change probably at the time when he entered the American service. His career was altogether a most singular one, presenting phases to the full asromantic as any of those undergone by a hero of fiction. The son of a small farmer near Dumfries, we find him manifesting from his boyhood a strong predilection for the sea, and at the age of twelve commencing life as a cabin-boy, on board the Friendship of Whitehaven, trading to Virginia. After completing his apprenticeship, he made several voyages in connection with the slave-trade to the West Indies, and rose to the position of master. He speedily, however, it is said, conceived a disgust to the traffic, and abandoned it. We find him, about 1775, accepting a commission in the American navy, then newly formed in opposition to that of Britain. What inspired. Paul with such feelings of rancour against his native country, cannot now be ascertained; but to the end of his life he seemed to retain undiminished the most implacable resentment towards the British nation. The cause of the colonies against the mother-country, now generally admitted to have been a just one, was adopted by him with the utmost enthusiasm, and certainly he contrived to inflict a considerable amount of damage on British shipping in the course of his cruises. To the British nation, and to Scotchmen more especially, the name of Paul Jones has heretofore only been suggestive of a daring pirate or lawless adventurer. He appears, in reality, to have been a sincere and enthusiastic partisan of the cause of the colonists, many of whom were as much natives of Britain as himself, and yet have never been specially blamed for their partisanship. In personal respects, he was a gallant and resolute man, of romantically chivalrous feelings, and superior to everything like a mean or shabby action. It is particularly pleasant to remark his disinterestedness in restoring, in after-years, to the Countess of Selkirk, the family-plate which the necessity of satisfying his men had compelled him to deprive her of; on the occasion of his descent on the Scottish coast, and for which he paid them the value out of his own resources. The letters addressed by him on this subject to the countess and her husband, do great credit both to his generosity and abilities in point of literary composition. By the Americans, Admiral Paul Jones is regarded as one of their most distinguished naval celebrities. MONEY THAT CAME IN THE DARKThe following simply-told narrative, though not so very wonderful as to shock our credulity, contains a pleasing spice of mystery, from its want of a direct explanation. It was found, under the date of September 23, 1673, in an old memorandum-book; that had belonged to a certain Paul Bowes, Esq., of the Middle Temple. A little more than a hundred years later, in 1783, the book, and one of the mysteriously-found pieces of money, was in the possession of an Essex gentleman, a lineal descendant of the fortunate Mr. Bowes. About the year 1658, after I had been some years settled in the Middle Temple, in a chamber in Elm Court, up three pair of stairs, one night as I came into the chamber, in the dark, I went into my study, in the dark, to lay down my gloves, upon the table in my study, for I then, being my own man, placed my things in their certain places, that I could go to them in the dark; and as I laid my gloves down, I felt under my hand a piece of money, which I then supposed, by feeling, to be a shilling; but when I had light, I found it a twenty-shilling piece of gold. I did a little reflect how it might come there, yet could not satisfy my own thoughts, for I had no client then, it being several years before I was called to the bar, and I had few visitors that could drop it there, and no friends in town that might designedly lay it there as a bait, to encourage me at my studies; and although I was the master of some gold, yet I had so few pieces, I well knew it was none of my number; but, however, this being the first time I found gold, I supposed it left there by some means I could not guess at. About three weeks after, coming again into my chamber in the dark, and laying down my gloves at the same place in my study, I felt under my hand a piece of money, which also proved a twenty-shilling piece of gold; this moved me to further consideration; but, after all my thoughtfulness, I could not imagine any probable way how the gold could come there, but I do not remember that I ever found any, when I went with those expectations and desires. About a month after the second time, coming into my chamber, in the dark, and laying down my gloves upon the same place, on the table in my study, I found two pieces of money under my hand, which, after I had lighted my candle, I found to be two twenty-shilling pieces; and, about the distance of six weeks after, in the same place, and in the dark, I found another piece of gold, and this about the distance of a month, or five or six weeks. I several times after, at the same place, and always in the dark, found twenty-shilling pieces of gold; at length, being with my cousin Langton, grandmother to my cousin Susan Skipwith, lately married to Sir John Williams, I told her this story, and I do not remember that I ever found any gold there after, although I kept that chamber above two years longer, before I sold it to Mr. Anthony Weldon, who now hath it (this being 23rd September 1673). Thus I have, to the best of my remembrance, truly stated this fact, but could never know, or have any probable conjecture, how that gold was laid there. The relationship that existed between cousin Langton and cousin Skipwith does not seem very clear, according to our modern method of reckoning kindred; but it must be recollected that, in former times, the title of cousin was given to any collateral relative more remote than a brother or sister. Probably, cousin Langton was Mr. Bowes's grandmother as well as Miss Skipwith's, and, if she liked, could have solved the mystery. For the writer has known more than one instance of benevolent old ladies making presents of money to young relatives, in a similarly stealthy and eccentric manner. |