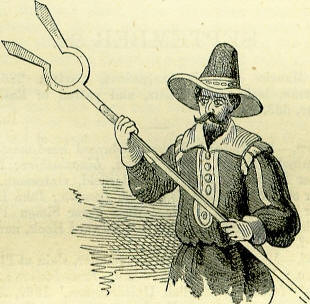

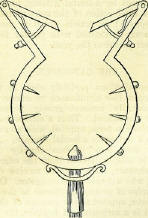

21st SeptemberBorn: John Loudon M'Adam, improver of roads, 1756; Louis Bonaparte, king of Holland, 1778, Ajaccio, Corsica. Died: Edward II of England, murdered at Berkeley Castle, 1327; Sultan Selim I 1520; Emperor Charles V, 1558, Monastery of St. Just, Spain; Colonel James Gardiner, killed at Prestonpans, 1745; John Balguy, eminent divine and controversial writer, 1748, Harrow-gate. Feast Day: St. Matthew, apostle and evangelist. St. Maura, virgin, 850. St. Lo or Laudus, bishop of Coutances, 568. QUEEN ISABELLA: ENGLISH DOMESTIC LIFE OF FIVE HUNDRED YEARS SINCEOne of the most interesting records of the domestic life of our ancestors that we remember to have read of late, consists of certain notices of the last days of Isabella, queen of Edward II, drawn from an account of the expenses of her household, in one of the Cottonian manuscripts in the British Museum, and lately communicated to the Society of Antiquaries by Mr. E. A. Bond. No Court Circular ever recorded the movements of royalty more minutely than does this memorial of the domestic manners of the middle of the fourteenth century-the private life of five hundred years since! It will be recollected that after the deposition and murder of King Edward II, we hear little of the history of the chief mover of these fearful events. The ambitious Mortimer expiates his crimes on the scaffold. Isabella, the instigator of sedition against her king, the betrayer of her husband, survives her accomplice; but from the moment that her career of guilt is arrested, she is no more spoken of. After mentioning the execution of Mortimer, Froissart tells us that 'the king, by the advice of his council, ordered his mother to be confined in a goodly castle, and gave her plenty of ladies to wait and attend on her, as well as knights and esquires of honour. He made her a handsome allowance to keep and maintain the state she had been used to, but forbade that she should ever go out, or drive herself abroad, except at certain times, when any shows were exhibited in the court of the castle; the queen thus passed her time there meekly, and the king, her son, visited her twice or thrice a year.' Castle Rising was the place of her confinement. After the first two years, the strictness of her seclusion was relaxed, and thence she was removed to Hertford Castle. The account of the expenses of her household embraces, in distinct divisions, the queen's general daily expenses; sums given in alms; miscellaneous necessary expenses; disbursements for dress, purchases of plate and jewellery, gifts, payments to messengers, and imprests for various services. In the margin of the general daily expenses are entered the names of the visitors during the day, together with the movements of the household from place to place. From these entries we gain some insight into the degree of personal freedom enjoyed by the queen and her connections; the consideration she obtained at the court of the great King Edward III, her son; and even into her personal disposition and occupations. It appears, then, that at the beginning of October 1357, the queen was residing at her castle at Hertford, having not very long before been at Rising. The first visitor mentioned, and who supped with her, was Joan, her niece, who visited the queen constantly, and nursed her in her last illness. About the middle of October, the queen set out from Hertford on a pilgrimage to Canterbury. She rested at Tottenham, London, Eltham, Dartford, and Rochester, in going or returning, visited Leeds Castle, and was again at Hertford at the beginning of November. She gave alms to the nuns-minoresses without Aldgate; to the rector of St. Edmund's, London, in whose parish her hostel was situated-it was in Lombard Street; and to the prisoners in Newgate. On the 26th of October, she entertained the king and Prince of Wales at her house in Lombard Street; and we find recorded a gift of 13s. 4d. to four minstrels, who played in their presence. After her return to Hertford Castle, the queen was visited by the renowned Gascon writer, the Captal de Buche, cousin of the Comte de Foix. He had recently come over to England with the Prince of Wales, having taken part, on the English side, in the great battle of Poitiers; and there are also entries of the visits of several noble captives, who were taken in the above engagement. On the 10th of February, messengers arrive from the king of Navarre, to announce, as it appears elsewhere, his escape from captivity; an indication that Isabella was still busy in the stirring events of her native country. On the 20th of March, the king comes to supper. On each day of the first half of the month of May, during the queen's stay in Loudon, the entries show her guests at dinner, her visitors after dinner, and at supper, as formally as in a Court Circular of our time. On May 14, Isabella left London, and rested at Tottenham, on her way to Hertford; and there is entered a gift of 6s. 8d. to the nuns of Cheshunt, who met the queen at the cross, in the high-road, in front of their house. On the 4th of June, the queen made another pilgrimage to Canterbury, where she entertained the abbot of St. Augustine's; under 'Alms' are recorded. the queen's oblations at the tomb of St. Thomas; here, too, are entered a payment to minstrels, her oblations in the church of St. Augustine, and her donations to various hospitals and religious houses in Canterbury. The entries of 'alms' amount to the considerable sum of £298, equivalent to about £3000 of present money. They consist of chapel-offerings, donations to religious houses, to clergymen preaching in the queen's presence, to special applicants for charity, and to paupers. The most interesting entry, perhaps, is that of a donation of 40s. to the abbess and minoresses without Aldgate, in London, to purchase for themselves two pittances on the anniversaries of Edward, late king of England, and Sir John, of Eltham (the queen's son), given on the 20th of November. And this is the sole instance of any mention of the unhappy Edward II. Among these items is a payment to the nuns of Cheshunt, whenever the queen passed the priory, in going to or from Hertford. There is more than one entry of alms given to poor scholars of Oxford, who had come to ask aid of the queen. A distribution is made amongst a hundred or fifty poor persons on the principal festivals of the year, amongst which that of Queen Katherine is included; and doles are made among paupers daily and weekly throughout the year, amounting in one year and a month, to £102. On the 12th of September, after the queen's death, a payment of 20s. is made to William Ladde, of Shene, on account of the burning of his house by an accident while the queen was staying at Shene. Under the head of 'Necessaries,' we find a payment of 50s. to carpenters, plasterers, and tilers, for works in the queen's chamber. Next are half-yearly payments of 25s. 2d. to the prioress of St. Helen's, in London; and rent for the queen's house in Lombard. Street. Next, is a purchase of two small 'catastre,' or cages for birds, in the queen's chamber, and of hemp-seed for the birds; and under the 'Gifts' are two small birch presented to Isabella by the king. Here, likewise, are payments for binding the black carpet in the queen's chamber; for repairs of the castle; lining of the queen's chariot with coloured cloth; repairs of the queen's bath, and gathering of herbs for it; for skins of vellum for writing the queen's books; and for writing a book of divers matters for the queen, 14s., including cost of parchment. Also, to Richard, Painter, for azure for illuminating the queen's books. Here payment is entered of the sum of £200, borrowed of Richard, Earl of Arundel. Here are entries of the purchase of an embroidered saddle, with gold fittings, and a black palfrey given to the queen of Scotland; and a payment to Louis de Rocan, merchant, of the Society of Malebaill, in London, for two mules, bought by him at Avignon, for the queen, £28, 13s.; the mules arrived after the queen's death, and they were delivered over to the king. The entries relating to jewels show that the serious events of Isabella's life, and her increasing years, had not overcome her natural passion for personal display. The total amount expended in jewels is no less than £1399, equivalent to about £16,000 of our present currency; 'and,' says Mr. Bond, 'after ample allowance for the acknowledged general habit of indulgence in personal ornaments belonging to the period, we cannot but consider Isabella's outlay on her trinkets as extravagant, and as betraying a more than common weakness for these, vain luxuries. The more costly of them were purchased of Italian merchants. Her principal English jewellers appear to have been John de Louthe and William de Berkinge, goldsmiths, of London' In a general entry of a payment of £421, are included items of a chaplet of gold, set with 'bulays' (rubies), sapphires, emeralds, diamonds, and pearls, price £105; divers pearls, £87; a crown of gold, set with sapphires, rubies of Alexandria, and pearls, price £80; these ornaments being, there is no doubt, ordered for the occasion of Isabella's visit to Windsor, at the celebration of St. George's Day. Among others, is a payment of £32 for several articles-namely, for a girdle of silk, studded with silver, 20s.; 300 doublets (rubies), at 20d. the hundred; 1800 pearls, at 2d. each; and a circlet of gold, at the price of £60, bought for the marriage of Katherine Brouart; and another of a pair of tablets of gold, enamelled with divers histories, of the price of £9. The division of 'Dona,' besides entries of simple presents and gratuities, contains records of gifts to messengers, from acquaintances and others, giving us further insight into the connections maintained by the queen. Notices of messengers bringing letters from the Countesses of Warren and Pembroke are very frequent. Under the head of ' Prraestita,' is an entry of £230, given to Sir Thomas de la March, in money paid to him by the hands of Henry Pickard (doubtless, the magnificent lord mayor of that name, who so royally entertained King John of France, the king of Cyprus, and the Prince of Wales at this period), as a loan from Queen Isabella, on the obligatory letter of the said Sir Thomas; for he is known as the victor in a duel, fought at Windsor, in presence of Edward III, with Sir John Viscomte in 1350. Several payments to couriers refer to the liberation of Charles, king of Navarre; and are important, as proving that the queen was connected with one who was playing a conspicuous part in the internal history of her native country-Charles of Navarre, perhaps the most unprincipled sovereign of his age, and known as 'the Wicked.' Among the remaining notices of messengers and letters, we have mention of the king's butler coming to the queen at Hertford, with letters of the king, and a present of three pipes of wine; a messenger from the king with three pipes of Gascon wine; another with a present of small birds; John of Paris, coming from the king of France to the queen at Hertford, and returning with two volumes of Lancelot and the Sang Real, sent to the same king by Isabella; a messenger bringing a boar's head and breast from the Duke of Lancaster, Henry Plantagenet; Wilson Orloger, monk of St. Albans, bringing to the queen several quadrants of copper; a messenger bringing a present of a falcon from the king; a present of a wild-boar from the king, and a cask of Gascon wine; a messenger bringing a present of twenty-four bream from the Countess of Clare; and payments to messengers bringing New-year's gifts from the king, Queen Philippa, the Countess of Pembroke, and Lady Wake. Payments to minstrels playing in the queen's presence occur often enough, to shew that Isabella greatly delighted in this entertainment; and these are generally minstrels of the king, prince, or of noblemen. We find a curious entry of a payment of 13s. 4d. to Walter Heat, one of the queen's 'vigiles' (viol-players), going to London, and staying there, in order to learn minstrelsy at Lent time; and, again, of a further sum to the same, on his return from London, 'de scola minstralsie.' Among the special presents by the queen are New-year's gifts to the ladies of her chamber, eight in number, of 100s. to each; and 20s. each to thirty-three clerks and squires; a girdle to Edward de Keilbergh, the queen's ward; a donation of 40s. to Master Lawrence, the surgeon, for attendance on the queen; a present of fur to the Countess of Warren; a small gift to Isabella Spicer, 'filiolae regime,' her goddaughter; and a present of £66 to Isabella de St. Rol, lady of the queen's chamber, on occasion of her marriage with Edward Brouart. Among the 'Messengers' payments we find a letter to the prior of Westminster, 'for a certain falcon of the Count of Tancarville lost, and found by the said prior.' Respecting Isabella's death, she is stated by chroniclers to have sunk, in the course of a single day, under the effect of a too powerful medicine, administered at her own desire. From several entries, however, in this account, she appears to have received medical treatment for some time previous to her decease. She expired on the 23rd of August; but, as early as February 15th, a payment had been made to a messenger going on three several occasions to London, for divers medicines for the queen, and for the hire of a horse for Master Lawrence, the physician, and again, for another journey by night to London. On the same day, a second payment was made to the same messenger for two other journeys by night to London, and two to St. Albans, to procure medicines for the queen. On the 1st of August, payment was made to Nicholas Thomasyer, apothecary, of London, for divers spices and ointments supplied for the queen's use. Among other entries, is a payment to Master Lawrence of 40s. for attendance on the queen and the queen of Scotland, at Hertford, for an entire month. It is evident that the body of the queen remained in the chapel of the castle until the 23rd of November, as a payment is made to fourteen poor persons for watching the queen's corpse there, day and night, from Saturday the 25th of August to the above date; each person receiving two pence daily, besides his food. The queen died at Hertford on August 22nd, 1358, and was buried in the church of the Grey Friars, within Newgate, the site of the present Christ Church. Large rewards, amounting together to £540, were given after Isabella's death, by the king's order, to her several servants, for their good service to the queen in her lifetime. THE AUTUMNAL EQUINOXOn or about the 21st of September and 21st of March, the ecliptic or great circle which the sun appears to describe in the heavens, in the course of the year crosses the terrestrial equator. The point of intersection is termed the equinoctial point or the equinox, because at that period, from its position in relation to the sun, the earth, as it revolves on its axis, has exactly one-half of its surface illuminated by the sun's rays, whilst the other half remains in darkness, producing the phenomenon of equal day and night all over the world. At these two periods, termed respectively, from the seasons in which they occur, the autumnal and the vernal equinox, the sun rises about six o'clock in the morning, and sets nearly at the same time in the evening. From the difference between the conventional and the actual or solar year, the former consisting only of 365 days, while the latter contains 365 days and nearly six hours (making the additional day in leap-year), the date at which the sun is actually on the equinox, varies in different years, from the 20th to the 23rd of the month. In the autumnal equinox, the sun is passing from north to south, and consequently from this period the days in the northern hemisphere gradually shorten till, on 21st December, the winter solstice is reached, from which period they gradually lengthen to the spring or vernal equinox on 21st March, when day and night are again equal. The sun then crosses the equator from south to north, and the days continue to lengthen up to the 21st of June, or summer solstice, from which they diminish, and are again equal with the nights at the autumnal equinox or 21st of September. Owing to the spheroidal form of the earth causing a protuberance of matter at the equator, on which the sun exercises a disturbing influence, the points at which the ecliptic cuts the equator, experience a constant change. They, that is the equinoxes, are always receding westwards in the heavens, to the amount annually of 50'.3, causing the sun to arrive at each intersection about 20' earlier than he did on the preceding year. The effect of this movement is, that from the time the ecliptic was originally divided by the ancients into twelve arcs or signs, the constellations which at that date coincided with these divisions now no longer coincide. Every constellation having since then advanced 30° or a whole sign forwards, the constellation of Aries or the Ram, for example, occupies now the division of the ecliptic called Taurus, whilst the division known as Aries, is distinguished by the constellation Pisces. In about 24,000 years, or 26,000 from the first division of the ecliptic, the equinoctial point will have made a complete revolution round this great circle, and the signs and constellations as originally marked out will again exactly coincide. The movement which we have thus endeavoured to explain, forms the astronomical revolution called the precession of the equinoxes, for the proper ascertainment and demonstration of which, science is indebted to the great French mathematician, D'Alembert. In connection with the ecliptic and equator, the mutual intersection of which marks the equinoctial point, an interesting question is suggested in reference to the seasons. It is well known that the obliquity of the ecliptic to the equator, at present about 23°, is diminishing at the rate of about 50 seconds in a century. Were this to continue, the two circles would at last coincide, and the earth would enjoy in consequence a perpetual spring. There is, however, a limit to this decrease or obliquity, which it has been calculated has been going on from the year 2000 B. C., and will reach its maximum about 6600 A. D. From that period the process will be reversed, and the obliquity gradually increase till a point is reached at which it will again diminish. From this variation in the position of the ecliptic, with regard to the equator, some have endeavoured to explain a change of climate and temperature, which it is imagined the world has gradually experienced, occasioning a slighter contrast between the seasons than formerly, when the winters were much colder, and the summers much hotter than they are at present. It is believed, however, that, whatever truth there may be in the allegations regarding a more equable temperature, throughout the year in modern times, it is not to the variation of the obliquity of the ecliptic that we are to look for a solution of the question. The entire amount of this variation is very small, ranging only from 23° 53' when the obliquity is greatest, to 22° 54' when it is least, and it is therefore hardly capable of making any sensible alteration on the seasons. As is well known, both the autumnal and vernal equinoxes are distinguished over the world by the storms which prevail at these seasons. The origin of such atmospheric commotions has never yet been very satisfactorily explained, but is sup-posed, as stated by Admiral Fitzroy, to arise from the united tidal action of the sun and moon upon the atmosphere; an action which at the time of the equinoxes is exerted with greater force than at any other period of the year. THE CATCHPOLE Many appellations perfectly clear in the days of their origin, lose significance in course of time, and occasionally become grossly perverted, or absolutely caricatured. Thus a villain was origin-ally a distinctive term, applied, with no evil significance, to a serf upon a feudal domain. A cheater has, like that, now become equally offensive, though it is simply derived from the officer of the king's exchequer, appointed to receive dues and taxes, and who was called the escheator. One of the best examples of grotesque change is the appellation beef-eater, applied to the yeoman of the guard, and which is a caricature of buffetier, the guardian of the buffet on occasions of state banqueting. The law-officer whose business was to apprehend criminals, was long popularly known as the catch-pole; but few remembered that he obtained that designation, because he originally carried with him a pole fitted by a peculiar apparatus to catch a flying offender by the neck. Our cut, [above] copied from a Dutch engraving dated 1626, represents an officer about to make such a capture. The pole was about six feet in length, and the steel implement at its summit was sufficiently flexible to allow the neck to slip past the V-shaped arms, and so into the collar; when the criminal was at the mercy of the officer to be pushed forward to prison, or dragged behind him.  This was the simplest form of the catchpole, sometimes it was a much more formidable thing, as will be more readily understood from our second cut copied from the antique instrument itself, obtained at Wurtzburg, in Bavaria. The fork at the upper part is strengthened by double springs, allowing the neck to pass freely, but acting as a check against its return; rows of sharp spikes are set round the collar, and would severely punish any violent struggler for liberty, whose neck it had once embraced. The criminal was, in fact, garrotted by the officer of the law, according to the most approved fashion of 'the good old times,' when justice was armed with terrors, and indulged in many cruelties now happily unknown. |