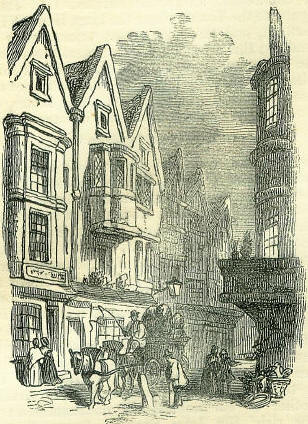

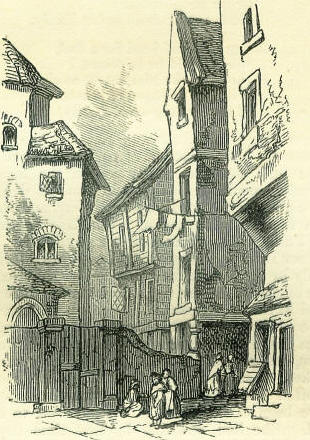

2nd SeptemberBorn: John Howard, philanthropist, 1726, Hackney. Died: Alice Lisle, executed for sheltering a rebel, 1685; Marie Therese, Princesse de Lamballe, murdered by a revolutionary mob, 1792, Paris; General Jean Victor Moreau, mortally wounded at battle of Dresden, 1813. Feast Day: St. Justus, archbishop of Lyon, confessor, about 390. St. Stephen, king of Hungary, confessor, 1038. St. William, bishop of Roschild, confessor, 1067. Blessed Margaret, virgin and martyr, 13th century. LORD HERVEY - DREAD OF HAPPINESSSeptember 2nd, 1768, died Mary Lepell, Lady Hervey, celebrated for her beauty, wit, and good sense at the court of the second George. In one of her letters, dated April 5th, 1750, after expressing her pity for the Countess of Dalkeith in losing her husband, she says: 'I dread to see people I care for quite easy and happy. I always wish them some little disappointment or rub, for fear of a greater; for I look upon felicity in this world not to be a natural state, and consequently what cannot subsist: the further, there-fore, we are put out of our natural position, with the more violence we return to it? It is worthy of note, that Sir Humphry Davy entertained a similar view of human happiness. He enters in his journal, in the midst of the most triumphant period of his life: 'Beware of too much prosperity and popularity. Life is made up of mixed passages-dark and bright, sunshine and gloom. The unnatural and excessive greatness of fortune of Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon-the first died after divine honours were paid him; the second gained empire, the consummation of his ambition, and lost his life immediately; the third, from a private individual, became master of continental Europe, and allied to the oldest dynasty, and after his elevation, his fortune immediately began to fall. Even in private life too much prosperity either injures the moral man and occasions conduct which ends in suffering, or is accompanied by the workings of envy, calumny, and malevolence of others.' JOHN HOWARDTo the service of a heart of the tenderest pity, John Howard united consummate skill in business, and a conscientiousness which no danger nor tedium could baffle. Burke's summary of his labours, happily spoken in parliament whilst Howard lived to hear them recognised, has never been superseded in grace and faithfulness: 'He has visited all Europe-not to survey the sumptuonsness of palaces, or the stateliness of temples; not to make accurate measurements of the remains of ancient grandeur, nor to form a scale of the curiosities of modern art; not to collect medals or to collate manuscripts; but, to dive into the depths of dungeons, to plunge into the infection of hospitals, to survey the mansions of sorrow and pain; to take the gauge and dimensions of misery, depression, and contempt; to remember the for-gotten, to attend to the neglected, to visit the forsaken, and to compare and collate the distresses of all men in all countries. His plan is original: it is as full of genius as of humanity. It was a voyage of discovery; a circumnavigation of charity.' Howard came of a mercantile stock, and his commercial training was not the least element in his usefulness. His father was a retired London merchant, who, when his son's schooling was over, bound him apprentice to Newnham and Shipley, wholesale grocers of Watling Street, City, paying down £700 as premium. In the warehouse and countingroom, Howard continued until his father's death, in 1742, placed fortune in his hands. From a child he had been delicate, he had lost his mother in infancy, and city air and hard work had reduced his strength almost to prostration. He, therefore, purchased the remnant of his apprenticeship, and, in order to recruit his vigour, set out on a French and Italian tour. On his return to London, he retired to lodgings in the suburban village of Stoke Newington. He was an invalid, weak, low-spirited, and restless, and falling seriously ill, was confined to bed for several weeks. His landlady, Mrs. Sarah Lardeau, a widow, eked out a narrow income by letting apartments. To Howard, in his sickness, she behaved with all the tenderness of a mother, and the young man, on his recovery, questioned with himself how he should reward her. Overcome with gratitude, he decided to offer her his hand and fortune in marriage. He was twenty-five, she was fifty-two. She was a good and prudent woman, and refused him with all natural and obvious reasons. He, however, was determined, asserted that he felt it his duty to snake her his wife, and that yield she must. In the end she consented, and, strange to say, the odd union proved a happy one. For three years they dwelt together in perfect amity, until her death made him a widower so miserable, that Stoke Newington became unendurable, and for change of scene and relief, he set sail for Lisbon, with the design of relieving the sufferers by the terrible earthquake of that year, 1755; but Lisbon he never reached. England and France were at war, and on the voyage thither, his vessel was captured, and the crew and passengers carried into the port of Brest, where they were treated with the utmost barbarity, and Howard experienced the horrors of prison-life for the first time in his own person. On his release and return to England, he settled on a small patrimonial estate at Cardington, near Bedford, and, in 1758, contracted his second marriage with Henrietta Leeds, the daughter of a lawyer, with whom he made the stipulation, that, in all matters in which there should be a difference of opinion between them, his voice should rule. She appears to have made him an admirable wife, and to have entered heartily into the charitable schemes whereby he blessed his neighbourhood and expended a large portion of his income. They built improved cottages, established schools, administered to the sick, and relieved the necessitous. Howard likewise dabbled in science, and was elected a member of the Royal Society. Medicine the was compelled to study in his care of the poor, but astronomy and meteorology were his favourite pursuits. As an illustration of the rigorous and methodical spirit he brought to every undertaking, it is related that, at the bottom of his garden, he had placed a thermometer, and, as soon as the frosty weather set in, he used to leave his warm bed at two o'clock every morning, walk in the bitter air to his thermometer, examine it by his lamp, and write down its register-which done to his satisfaction, he would coolly betake himself again to bed. The quiet usefulness of his life at Cardington came to a melancholy termination by the death of his beloved wife in 1765, after giving birth to their only child, a son. Weak health and a heavy heart again induced him to seek relief in continental travel. On his renewed settlement at Cardington, he was, in 1773, elected sheriff of Bedford, and though ineligible, being a dissenter, he accepted, and was permitted to retain the office. Such a position to a man of Howard's temper could not possibly remain a sinecure, but at once drove him into active contact with the prisons of his county. Their inspection outraged alike his benevolence and justice. The cells were frequently damp, wet, dark, and ill ventilated, so that the phrase, 'to rot in prison,' was anything but a metaphor. In such noisome holes, innocence, misfortune, and vice were huddled together, and it was hard to say whether the physical or moral corruption was greater. Over these holds of wretchedness a jailer sat as extortioner of bribes and fees, and under him turnkeys, cruel and vicious, operated on their own account. From Bedford, Howard passed into the adjoining counties, and from thence into more distant parts, until he effected the tour of England, discovering everywhere abuses and horrors of which few had any conception. Howard's vocation was now fixed; the inspection and reformation of prisons became his business, and to the work he gave all his energies with a singleness of purpose and an assiduity which have placed his name in the first line of philanthropists. England alone was insufficient to exhaust his zeal; Europe he tracked from east to west, from north to south, and through the lazarettos of the Levant he passed as a ministering angel. The age was ripe for Howard. Kings and statesmen listened to his complaints and suggestions, and promised amendment. The revelations he was enabled to snake stirred the feelings of the good and enlightened to the uttermost, and provided material for philosophers like Bentham, and stimulus and direction for the kind-hearted, like Mrs. Fry. Howard printed his work, on the State of Prisons, at Warrington. He was attracted thither by the skill of Mr. Eyre, a printer, and the promise of literary assistance from Dr. Aiken, the brother of Mrs. Barbauld, then practising as surgeon in that town; and of Howard's habits, Dr. Aiken has recorded some interesting particulars. Every morning-though it was then in the depth of a severe winter-he rose at two o'clock precisely, washed, said his prayers, and then worked at his papers until seven, when he breakfasted and dressed for the day. Punctually at eight he repaired to the printing office, to inspect the progress of his sheets through the press. There he remained until one, when the compositors went to dinner. While they were absent, he would walk to his lodgings, and, putting some bread and dried fruit into his pocket, sally out for a stroll in the outskirts of the town, eating his hermit-fare as he trudged along, and drinking a glass of water begged at some cottage-door. This was his only dinner. By the time that the printers returned to the office, he had usually, but not always, wandered back. Sometimes he would call upon a friend on his way, and spend an hour or two in pleasant chat, for though severe with himself, the social instincts were largely developed in his nature. At the press, he remained until the men left off their day's toil, and then retired to his lodgings to tea or coffee, went through his religious exercises, and retired to rest at an early hour. Such was the usual course of a day at Warrington. Sometimes a doubt would suggest itself as to the precise truth of some statement, and though it might cost a journey of some hundreds of miles, off Howard would set, and the result would appear in a note of some insignificant modification of the text. Truth, Howard thought cheap at any price. Like Wesley, he ate no flesh and drank no wine or spirits. He bathed in cold water daily, ate little and at fixed intervals, went to bed early and rose early. Of this asceticism he made no show. After fair trial, he found that it suited his delicate constitution, and he persevered in it with unvarying resolution. Innkeepers would not welcome such a guest, but Howard was no niggard, and paid them as if he had fared on their meat and wine. He used to say, that in the expenses of a journey which must necessarily cost three or four hundred pounds, twenty or thirty pounds extra was not worth a thought. Beyond the safeguard of his simple regimen, the precautions Howard took to repel contagious diseases were no more than smelling at a phial of vinegar while in the infected cell, and washing and changing his apparel afterwards; but even these, in process of time, he abandoned as unnecessary. He was often pressed for his secret means of escaping infection, and usually replied: 'Next to the free goodness and mercy of the Author of my being, temperance and cleanliness are my preservatives. Trusting in divine Providence, and believing myself in the way of my duty, I visit the most noxious cells, and while thus employed, I fear no evil.' Howard died on the 20th of January 1790, at Kherson, in South Russia. THE GREAT FIRE OF LONDON London was only a few months freed from a desolating pestilence, it was suffering, with the country generally, under a most imprudent and ill-conducted war with Holland, when, on the evening of the 2nd of September 1666, a fire commenced by which about two-thirds of it were burned down, including the cathedral, the Royal Exchange, about a hundred parish churches, and a vast number of other public buildings. The conflagration commenced in the house of a baker named Farryner, at Pudding Lane, near the Tower, and, being favoured by a high wind, it continued for three nights and days, spreading gradually eastward, till it ended at a spot called Pye Corner, in Giltspur Street. Mr. John Evelyn has left us a very interesting description of the event, from his own observation, as follows: 'Sept. 2, 1666.-This fatal night, about ten, began that deplorable fire near Fish Streete in London. 'Sept. 3.-The fire continuing, after dinner I took coach with my wife and soon, and went to the Bankside in Southwark, where we beheld that dismal spectacle, the whole Citty in dreadful flames neare ye water side; all the houses from the Bridge, all Thames Street, and upwards towards Cheapeside downe to the Three Cranes, were now consum'd. 'The fire having continu'd all this night (if I may call that night which was as light as day for ten miles round about, after a dreadful manner)when conspiring with a fierce eastern wind in a very drie season; I went on foote to the same place, and saw the whole South part of ye Citty burning from Cheapeside to ye Thames, and all along Cornehill (for it kindl'd back against ye wind as well as forward), Tower Streete, Fen-church Streete, Gracious Streete, and so along to Bainard's Castle, and was now taking hold of St. Paule's Church, to which the scaffolds contributed exceedingly. The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonish'd, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirr'd to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or scene but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures, without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them, so as it burned both in breadth and length, the Churches, Public Halls, Exchange, Hospitals, Monuments, and ornaments, leaping after a prodigious manner from house to home and streete to streete, at greate distances one from ye other; for ye heate with a long set of faire and warme weather, had even ignited the air, and prepaid the materials to conceive the fire, which devour'd after an incredible manner, houses, furniture, and every thing. Here we saw the Thames cover'd with goods floating, all the barges and boates laden with what some had time and courage to save, as, on ye other, ye carts, &c., carrying out to the fields, which for many miles were strew'd with moveables of all sorts, and tents erecting to shelter both people and what goods they could get away. Oh the miserable and calamitous spectacle! such as haply the world had not scene the like since the foundation of it, nor to be outdone till the universal conflagration. All the skie was of a fiery aspect, like the top of a burning oven, the light scene above forty miles round about for many nights. God grant my eyes may never behold the like, now seeing above 10,000 houses all in one flame; the noise and cracking and thunder of the impetuous flames, ye shrieking of women and children, the hurry of people, the fall of Towers, Houses, and Churches, was like an hideous storme, and the aire all about so hot and inflam'd that at last one was not able to approach it, so that they were forc'd to stand still and let ye flames burn on, wch they did for neere two miles in length and one in bredth. The clouds of smoke were dismall, and reach'd upon computation neer fifty miles in length. Thus I left it this afternoone burning, a resemblance of Sodom, or the last day. London was, but is no more! 'Sept. 4 - The burning still rages, and it was now gotten as far as the Inner Temple, all Fleet Streete, the Old Bailey, Ludgate Hill, Warwick Lane, Newgate, Paul's Chain, Watling Streete, now flaming, and most of it reduc'd to ashes; the stones of Paules flew like granados, ye melting lead running downe the streetes in a streame, and the very pavements glowing with fiery rednesse, so as no horse nor man was able to tread on them, and the demolition had stopp'd all the passages, so that no help could be applied. The Eastern wind still more impetuously drove the flames forward. Nothing but ye Almighty power of God was able to stop them, for vain was ye help of man. 'Sept. 5.-It crossed towards Whitehall; Oh the confusion there was then at that Court! It pleas'd his Maty to command me among ye rest to looke after the quenching of Fetter Lane, and to pre-serve if possible that part of Holborn, while the rest of ye gentlemen tooke their several posts (for now they began to bestir themselves, and not till now, who hitherto had stood as men intoxicated, with their hands acrosse), and began to consider that nothing was likely to put a stop but the blowing up of so many houses as might make a wider gap than any had yet ben made by the ordinary method of pulling them down with engines; this some stout seamen propos'd early enough to have sav'd neare ye whole Citty, but this some tenacious and avaritious men, aldermen, &c., would not permit, because their houses must have ben of the first. It was therefore now commanded to be practic'd, and my concern being particularly for the hospital of St. Bartholomew neere Smithfield, where I had many wounded and sick men, made me the more diligent to promote it, nor was my care for the Savoy lesse. It now pleas'd God by abating the wind, and by the industry of ye people, infusing a new spirit into them, that the fury of it began sensibly to abate about noone, so as it came no farther than ye Temple Westward, nor than ye entrance of Smith-field North; but continu'd all this day and night so impetuous towards Cripplegate and the Tower, as made us all despaire: it also broke out againe in the Temple, but the courage of the multitude persisting, and many houses being blown up, such gaps and desolations were soone made, as with the former three days' consumption, the back fire did not so vehemently urge upon the rest as formerly. There was yet no standing neere the burning and glowing ruins by neere a furlong's space. 'The poore inhabitants were dispers'd about St. George's Fields, and Moorefields, as far as Highgate, and severall miles in circle, some under tents, some under miserable butts and hovells, many without a rag or any necessary utensills, bed or board, who from delicatenesse, riches, and easy accommodations in stately and well-fumish'd houses, were now reduc'd to extreamest misery and poverty. 'In this calamitous condition I return'd with a sad heart to my house, blessing and adoring. the mercy of God to me and mine, who in the midst of all this ruine was like Lot, in my little Zoar, safe and sound. 'Sept. 7.-I went this morning on foote from Whitehall as far as London Bridge, thro' the late Fleete Streete, Ludgate Hill, by St. Paules, Cheapeside, Exchange, Bishopsgate, Aldersgate, and out to Moorefields, thence thro' Cornehille, &c., with extraordinary difficulty, clambering over heaps of yet smoking rubbish, and frequently mistaking where I was. The ground under my feete was so hot, that it even burnt the soles of my shoes. In the mean time his Maty got to the Tower by water, to demolish ye houses about the graff, which being built intirely about it, had they taken fire and attack'd the White Tower where the magazine of powder lay, would undoubtedly not only have beaten downe and destroy'd all ye bridge, but make and tome the vessells in ye river, and render'd ye demolition beyond all expression for several miles about the countrey. 'At my return I was infinitely concern'd to find that goodly Church St. Paules now a sad ruine, and that beautifall portico (for structure comparable to any in Europe, as not long before repair'd by the King) now rent in pieces, flakes of vast stone split asunder, and nothing remaining intire but the inscription in the architrave, shewing by whom it was built, which had not one letter of it defac'd. It was astonishing to see what immense stones the heat had in a manner calcin'd, so that all ye ornaments, columns, freezes, and projectures of massie Portland stone flew off, even to ye very roofe, where a sheet of lead covering a great space was totally mealted; the mines of the vaulted roofe falling broke into St. Faith's, which being fill'd with the magazines of bookes belonging to ye stationers, and carried thither for safety, they were all consum'd, burning for a weeke following. It is also observable that ye lead over ye altar at ye East end was untouch'd, and among the divers monuments, the body of one Bishop remain'd intire. Thus lay in ashes that most venerable Church, one of the most antient pieces of early piety in ye Christian world, besides neere 100 more. The lead, yron worke, bells, plate, &c. mealted; the exquisitely wrought Mercers Chapell, the sumptuous Exchange, ye august fabriq of Christ Church, all ye rest of the Companies Halls, sumptuous buildings, arches, all in dust; the fountains dried up and ruin'd whilst the very waters remain'd boiling; the vorrago's of subterranean cellars, wells, and dungeons, formerly ware-houses, still burning in stench and dark clouds of smoke, so that in five or six miles traversing about I did not see one load of timber unconsum'd, nor many stones but what were calcin'd white as snow. The people who now walk'd about ye ruines appear'd like men in a dismal desart, or rather in some greate citty laid waste by a cruel enemy; to which was added the stench that came from some poore creatures bodies, beds, &c. Sir Thomas Gresham's statue, tho' fallen from its nich in the Royal Exchange, remain'd intire, when all those of ye Kings since ye Conquest were broken to pieces, also the standard in Cornehill, and Q. Elizabeth's effigies, with some armes on Ludgate, continued with but little detriment, whilst the vast yron chaines of the Cittie streetes, hinges, bars and gates of prisons, were many of them merited and reduced to cinders by ye vehement heate. I was not able to passe through any of the narrow streetes, but kept the widest, the ground and aire, smoake and fiery vapour, continu'd so intense that my haire was almost sing'd, and my feete unsufferably heated. The bie lanes and narrower streetes were quite fill'd up with rubbish, nor could one have knowne where he was, but by ye ruines of some Church or Hall, that had some remarkable tower or pinnacle remaining. I then went towards Islington and Highgate, where one might have seene 200,000 people of all ranks and degrees dispers'd and lying along by their heapes of what they could save from the fire, deploring their losse, and tho' ready to perish for hunger and destitution, yet not asking one penny for relief; which to me appear'd a stranger sight than any I had yet beheld. RELICS OF LONDON SURVIVING THE FIREAt the time of the Great Fire, the walls of the City enfolded the larger number of its inhabitants. Densely packed they were in fetid lanes, overhung by old wooden houses, where pestilence had committed the most fearful ravages, and may be said to have always remained in a subdued form ready to burst forth. Suburban houses straggled along the great highways to the north; but the greater quantity lined the bank of the Thames toward Westminster, where court and parliament continually drew strangers. George Wither, the Puritanpoet, speaks of this in his Britain's Remembrancer, 1628: The Strand, that goodly thorow-fare betweene The Court and City; and where I have scene Well-nigh a million passing in one day. That industrious and accurate artist, Wenceslaus Hollar, busied himself from his old point of view, the tower of St. Mary Overies, or, as it is now called, St. Saviour's, Southwark, in delineating the appearance of the city as it lay in ruins. He afterwards engraved this, contrasting it with its appearance before the fire. From its contemplation, the awful character of the visitation can be fully felt. Within the City walls, and stretching beyond them to Fetter Lane westwardly, little but ruins remain; a few walls of public buildings, and a few church towers, mark certain great points for the eye to detect where busy streets once were. The whole of the City was burned to the walls, except a small portion to the north-east. We have, consequently, lost in London all those ancient edifices of historic interest-churches crowded with memorials of its inhabitants, and buildings consecrated by their associations-that give so great a charm to many old cities. The few relics of these left by the fire have become fewer, as changes have been made in our streets, or general alterations demanded by modern taste. It will be, however, a curious and not unworthy labour to briefly examine what still remains of Old London edifices erected before the fire, by which we may gain some idea of the general character of the old city. Of its grand centre-the Cathedral of St. Paul-we can now form a mental photograph when contemplating the excellent views of interior and exterior, as executed by Hollar for Dugdale's noble history of the sacred edifice. It was the pride of the citizens, although they permitted its 'long - drawn aisles' to be degraded into a public promenade, a general rendezvous for the idle and the dissolute. The authors, particularly the dramatic, of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, abound with allusions to 'the walks in Paul's;' and Dekker, in his Gull's Hornbook, devotes due space to the instruction of a young gallant, new upon town, how he is to behave in this test of London dandyism. The poor hangers-on of these new-fledged gulls, the Captains Bobadil, et hoc genus omne, hung about the aisles all day if they found no one to sponge upon. Hence came the phrase, to 'dine with Duke Humphrey,' as the tomb of that nobleman was the chief feature of the middle aisle; despite, however, of its general appropriation to him, it was in reality the tomb of Sir John Beauchamp, son to the Earl of Warwick, who died in 1538-having lived at Baynard's Castle, a palatial residence on the banks of the Thames, also destroyed in the fire. The next important monument in the Old Cathedral was that of Sir Christopher Hatton, the famous 'dancing chancellor' of Queen Elizabeth; and of this some few fragments remain, and are still preserved in the crypt of the present building. Along with them are placed other portions of monuments, to Sir Nicholas, the father of the great Lord Bacon; of Dean Colet, the founder of St. Paul's School; and of the poet, Dr. John Donne. The reflective eye will rest with much interest on these relics of the past, but especially on that of Donne, which has wonderfully withstood the action of the fire, and exactly agrees with Walton's description, in his memoir of the poet-dean, who lapped himself in his shroud, and so stood as a model to Nicholas Stone as he sculptured the work. Near St. Paul's, on the south side of Basing Lane, there existed, until a very few years since, the pillared vaults of an old Norman house, known as Gerrard's Hall; it is mentioned by Stow as the residence of John Gisors, mayor of London, 1245. It was an interesting and beautiful fragment; but after having withstood the changes of centuries, and the great fire in all its fury, it succumbed to the city improvements, and New Cannon Street now passes over its site. The old Guildhall, a favourable specimen of the architecture of the fifteenth century, withstood the fire bravely; portions of the old walls were incorporated with the restorations, and from a window in the library may still be seen one of the ancient south windows of the hall; it is a fair example of the perpendicular style, measuring 21 feet in height by 7 in width. The crypt beneath the hall is worth inspection, and so is the eastern side of the building. Such are the few fragments left us of all that the devouring element passed over. We shall, however, still find much of interest in that small eastern side of the city which escaped its ravages. At the angle where Mark Lane meets Fenchurch Street, behind the houses, is the picturesque church of All-hallows Staining, in the midst of a quaint old square of houses, with a churchyard and a few trees, giving it a singularly old-world look. The tower and a portion of the west end alone are ancient; the church escaped the fire, but the body of the building fell in, 1671 A. D. In this church, the Princess (afterwards Queen) Elizabeth per-formed her devotions, May 19, 1554, on her release from the Tower. The churchwarden's accounts contain some curious entries of rejoicings by bell-ringing on great public events.  The church of All-hallows, Barking, at the end of Tower Street, presents many features of interest, and helps us best to understand what we have lost by the Great Fire. One of the finest Flemish brasses in England is still upon its floor; it is most elaborately engraved and enamelled, and is to the memory of one Andrew Evyngar and his wife (circa 1535). Another, to that of William Thynne, calls up a grateful remembrance, that to him we owe, in 1532, the first edition of the works of that 'well of English undefiled'-Geoffrey Chaucer. Other brasses and quaint old tombs cover floor and walls. Here the poetic Earl of Surrey was hurriedly buried after his execution; so was Bishop Fisher, the friend of More; and Archbishop Laud ignominiously in the churchyard, but afterwards removed to honourable sepulture in St. John's College, Oxford. Keeping northward, across Tower Hill, we enter Crutched-friars, where stand the alms-houses erected by Sir John Milborn in 1535. He built them 'in honor of God, and of the Virgin;' and it is a somewhat remarkable thing, that a bas-relief representing the Assumption of the Virgin, in the conventional style of the middle ages, still remains over the entrance-gate. St. Olave, Hart Street, is the next nearest old church. Seen from the churchyard, it is a quaint and curious bit of Old London, with its churchyard-path and trees. Here lies Samuel Pepys, the diarist, to whom we all are so much indebted for the striking picture of the days of Charles II he has left to us. He lived in the parish, and often mentions 'our own church' in his diary. Upon the walls, we still see the tablet he placed to the memory of his wife. There are also tablets to William Turner, who published the first English Herbal in 1568; and to the witty and poetic comptroller of the navy, Sir John Mennys, who wrote some of the best poems in the Musarum Deliciae, 1656. St. Catherine Cree, on the north side of Leaden-hall Street, was rebuilt in 1629, and is chiefly remarkable for its consecration by Archbishop Laud, with an amount of ceremonial observance, particularly as regarded the communion, which led to an idea of his belief in transubstantiation, and was made one of the principal charges against him. The church contains a good recumbent effigy of Queen Elizabeth's chief butler, Sir Nicholas Throgmorton; and an inscription to R. Spencer, Turkey merchant, recording his death in 1667, after he had seen the prodigious changes in the state, the dreadful triumphs of death by pestilence, and the astonishing conflagration of the city by fire.' A little to the west, stands St. Andrew Under-shaft, abounding with quaint old associations. It takes its name from the high shaft of the May-pole, which the citizens used to set up before it, on every May-day, and which overtopped its tower. John Stow, who narrates this, lies buried within; and his monument, representing him at his literary labours, is one of the most interesting of its kind in London. It is not the only quaint mortuary memorial here worth looking on; there is among them the curious tomb of Sir Hugh Hammersley, with armed figures on each side. Opposite this church is a very fine Elizabethan house, from the windows of which the old inhabitants may have seen the setting -up of the old May-pole, and laughed at the tricks of the hobby-horse and fool, as they capered among the dancers. Passing up St. Mary Axe, we shall notice many good old mansions of the resident merchantmen of the last two centuries; and at the corner of Bevis Marks, a very old public-house, rejoicing in the sign of 'the Blue Pig.' The parish of St. Helen's, Bishopsgate, is the most interesting in London for its many old houses. The area and courts known as Great St. Helen's are particularly rich in fine examples, ranging from the time of Elizabeth to James II. No. 2 has a good doorway and staircase of the time of Charles I; Nos. 3 and 4 are of Elizabethan date, with characteristic corbels; while Nos. 8 and 9 are modern subdivisions of a very fine brick mansion, dated 1646, and most probably the work of Inigo Jones. No. 9 still possesses a very fine chimney-piece and staircase of carved oak. Crosby Hall is of course the great feature of this district, and is one of the finest architectural relics of the fifteenth century left in London; yet, after escaping the great fire, and the many vicissitudes every building in the heart of London is subjected to, it had a very narrow escape in 1831 of being ruthlessly destroyed; and had it not been for the public spirit of a lady, Miss Hackett, who lived beside it, and who by her munificence shamed others into aiding her, this historic mansion would have passed away from sight. It is now used as a lecture-hall or for public meetings; and an excellently designed modern house, in antique taste, leads into it from Bishops-gate Street. The timber roof, with its elegant open tracery, and enriched octagonal corbels hanging therefrom, cannot be exceeded by any architectural relic of its age; the Oriel window is also of great beauty. It was built by Sir John Crosby, a rich merchant, between 1466-1475, and his widow parted with it to Richard Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester, afterwards Richard III. Its contiguity to the Tower, where the king, Henry VI., was confined, and the unfortunate princes after him, rendered this a peculiarly convenient residence for the unscrupulous duke. Shakspeare has immortalised the place by laying one of the scenes of his great historical drama there. Gloucester, after directing the assassins to murder Clarence, adds: When you have done, repair to Crosby Place. Here, indeed, were the guilty plots hatched and consummated that led Richard through blood to the crown; and Shakspeare must have pondered over this old place, then more perfect and beautiful than now, for we know from the parish assessments, that he was a resident in St. Helen's in 1598, and must have lived in a house of importance from the sum levied. The tomb of Sir John Crosby is in the adjoining church of St. Helen's, and is one of the finest remaining in any London church; it has upon it the recumbent figures of himself and wife. The knight is fully armed, but wears over all his mantle as alderman, and round his neck a collar of suns and roses, the badge of the House of York. In this church also lies Sir Thomas Gresham, another of our noblest old merchantmen; and ' the rich' Sir John Spencer, from whom the Marquises of Northampton have derived-by marriage-so large a portion of their revenues. Passing up Bishopsgate Street, we may note many old houses, and a few inns, as well as the quaint church of St. Ethelburgha. In the house known as Crosby Hall Chambers, is a very fine chimney-piece, dated 1635. Many houses in this district are old, but have been new fronted and modernised. There is an Elizabethan house at the north corner of Houndsditch, and another at the corner of Devonshire Street, which has over one of its fire-places the arms of Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, the friend of Shakspeare. But the glory of the neighbourhood is the house of Sir Paul Pinder, nearly opposite; the finest old private house remaining in London. The quaint beauty of the facade is enhanced by an abundance of rich ornamental details, and the ceiling of the first-floor is a wonder of elaboration and beauty. Sir Paul was a Turkey merchant of great wealth, resident ambassador at Constantinople for upwards of nine years, in the early part of the reign of Janes I. He died in 1650, 'a worthie benefactor to the poore.'  Returning a few hundred yards, we get again within the Old-London boundary; and crossing Broad Street, the small church of Allhallows-on-the-Wall marks the site of a still smaller one of very ancient date; the wall beside it is upon the foundation of the old wall that encircled London, and which may be still traced at various parts of its course round the city, and is always met with in deep excavations.' Passing the church, we see to our left Great Winchester Street, which, in spite of some recent modernisation, is the most curious old street remaining within the city boundary, inasmuch as all its houses are old on both sides of the way; about twenty years ago, when the above sketch was made, it gave a perfect idea of a better-class street before the great fire. In the angle of this street, leading into Broad Street, are some fine old brick mansions of the Jacobean era; and to the west lies Carpenter's Hall, with curious paintings of the sixteenth century on its walls, ancient records and plate in its monument-room, and a large garden; joining on to the still larger Drapers' Garden, interesting examples of town-gardens' existing untouched from the middle ages. Austin Friars is contiguous: the old church here is a portion of the monastic building erected in 1354; the window-tracery is extremely elegant. Unfortunately, it is now a roofless ruin, injured by a fire last year, and no steps yet taken for its reparation; and thus another of our few historic monuments may soon pass away from the City. Keeping again to the line of the Old-London wall westward, we pass Coleman Street, and note some few good Elizabethan houses. Then comes Sion College, which was seriously injured, and one-third of the library consumed by the great fire. Aldermanbury Postern, nearly opposite, marks the site of a small gate, or ' postern' in the City wall leading to Finsbury Fields; the favourite resort of the Londoners in the summer evenings. And Hogsdone, Islington, and Tothnam-court, For cakes and creame, had then no small resort. So says George Wither, writing in 1628. To the eagerness of those in ` populous city pent,' to get out of its bounds, he testifies from his own observation: Some coached were, some horsed, and some walked, Here citizens, there students, many a one; Here two together; and, yon, one alone. Of Nymphes and Ladies, I have often ey'd A thousand walking at one evening-tide; As many gentlemen; and young and old Of meaner sort, as many ten times told. The alms-houses of the Clothworkers' Company occupy the angle of the City wall at Cripplegate; beneath the small chapel is a fine crypt in the Norman style, built of Caen stone, the groining decorated with zigzag moulding and spiral ornament. It is a fragment of the old 'Hermitage of St. James on the Wall,' and is a graceful and interesting close to our survey, for the fire travelled thus far to the north-west, and left the City no other early relics. Passing outside the City bounds, and into the churchyard of St. Giles's, Cripplegate, a very fine piece of the old wall may be seen, with a circular bastion at the angle, the upper part now converted into a garden for the alms-houses just spoken of. Another bastion, to the south, was converted by Inigo Jones into an apsidal termination of Barber-Surgeon's Hall. The church tower is a stone erection, the body of the church of brick, inside are monuments, second in interest to none. Here lies Fox, the martyrologist; Frobisher, the traveller; Speed, the historian; and one of England's greatest poets and noblest men- John Milton. The church-register records the marriage here of Oliver Cromwell. The range of houses in the main street, and the quaint old church-gate, were built in the year 1660; so short a time before the fire, that we may study in them the `latest fashions' of London-street architecture at that period. As there are some quaint and interesting buildings in the suburbs of this side of London, we may bestow a brief notice upon them, more particularly as they help us to comprehend its past state. There are still some Elizabethan houses leading toward Barbican; a few years ago, there were very many in this district. In Golden Lane, opposite, is the front of the old theatre, by some London topographers considered to be 'The Fortune,' by which Edward Alleyn, the founder of Dulwich College, made his estate; others say it is Killigrew's play-house, called 'The Nursery,' intended to be used as a school for young actors. Pepys records a visit there, in his quaint style, when `he found the musique better than we looked for, and the acting not much worse, because I expected as bad as could be.' There is a very old stucco representation of the Royal Arms and supporters over the door. Aldersgate Street preserves the remains of a noble town-house, erected by Inigo Jones for the Earls of Thanet; its name soon changed to Shaftesbury House, by which it is best known. On the opposite side, higher up the street, 'the City Auction-rooms ' are in a fine old mansion, with some pleasing enrichments of Elizabethan character. A short street beyond Barbican leads into a quiet square, and the entrance to Sutton's noble foundation-the Charter House. It still preserves much of its monastic look. The entrance-gate is of the fifteenth century, and over it was once placed the mangled limbs of its last prior, who was executed at Tyburn by command of Henry VIII.  The chapel, hall, and governor's room have fine old original enrichments. At the Smithfield end of Long Lane, are some old houses, but the best are in Cloth-fair and St. Bartholomew's Close. The churchyard entrance, with the old edifice, and row of ancient houses looking down upon it, seems not to belong to the present day, but to carry the visitor entirely back to the seventeenth century. There is a back-alley encroaching on the chancel, with tumble-down old houses supported on wooden pillars, which gives so perfect an idea of the crowded and filthy passages, once common in Old London, that we here engrave it. The houses are part of those erected by the Lord Rich, one of the most wicked and unscrupulous of the favourites of Henry VIII, and to whom the priory and precinct was given with great privileges. The church is one of the most ancient and interesting in London, with many fine fragments of its original Norman architecture; the houses of the neighbourhood are built over the conventual buildings, and include portions of them, such as the cloisters and refectory. Ascending Holborn Hill, we see in Ely Place the remains of the old chapel of the mansion once there, with a very fine decorated window. This was the town residence of the bishops of Ely from 1388. It was a pleasantly situated spot in the olden time, with its large orchards and gardens sloping toward the river Fleet. Shakspeare, on the authority of Holinshed, makes the crafty Duke of Gloucester (afterwards Richard III) pleasantly allude to its produce: My Lord of Ely, when I was last in Holborn, I saw good strawberries in your garden there; I do beseech you send for some of them. Saffron Hill, in the immediate neighbourhood, carries in its name the memory of its past floral glories; and Gerard, whose Great Herbal waspublished in the latter days of Elizabeth, dates his preface ' from my house in Holborn, in the suburbs of London.' We may walk as far as Staples Inn, opposite Gray's Inn Lane, to see the finest row of old houses of the early part of the seventeenth century remaining in London. The quaint old hall behind them, with its garden and fig-trees, pre-serves still a most antique air. In Chancery Lane, the fine old gate-house bears the date of 1518, and the brick-houses beside it have an extra interest in consequence of Fuller's assertion that Ben Jonson, when a young man, 'helped in the building, when having a trowel in one hand, he had a book in his pocket.' Passing toward Fleet Street, we meet with no old vestige, where, a few years since, they abounded. Beside the Temple Gate, is a good old Elizabethan house, with a fine plaster ceiling, with the initials and badges of Henry, Prince of Wales, son of James I. The Temple, with its round church and unique series of fine monumental effigies, brings us to the margin of the Thames, and is a noble conclusion to our survey, which the chances and changes of busy London may alter every forthcoming year. |