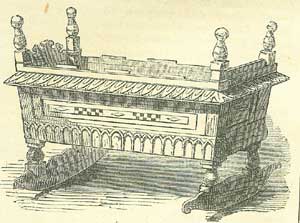

19th JuneBorn: James VI of Scotland, I of Great Britain, 1566, Edinburgh Castle; Plane Pascal, French religious writer, 1623, Clermont, in Auvergne; Philip van Limborch, Arminian theologian, 1633, Amsterdam. Died: St. Romuald, 1027, Ancona; Piers Gaveston, favourite of Edward II, executed 1312, Gaversyke; Dr. William Sherlock, Dean of St. Paul's, Master of the Temple, theologian, controversialist, 1707, Hampstead; Nicolas Lemery, one of the fathers of true chemistry, 1715, Paris; John Brown, D.D., Scotch Dissenting divine, author of the Self-lnterpreting Bible, Pc., 1787, Haddington; Sir Joseph Banks, naturalist, 1820, Spring Grove. Feast Day: Saints Gervasius and Protasius, martyrs, 1st century. St. Die or Deodatus, Bishop of Nevers and Abbot of Jointures, 679 or 680. St. Boniface, Archbishop of Magdeburg, Apostle of Russia and martyr, 1009. St. Juliano Falconieri, virgin, 1340. THE FÊTE DIEUThis day is kept by Roman Catholics as one of their highest festivals; it is held as a celebration of the name of God, when the people bring their offerings to him as the King of Heaven. The consecrated host is carried through the open air, the whole population turning out to do honour to it, and kneeling as it passes by. Such processions as we see in the streets on this day are evidently borrowed from heathen times: the paintings' which cover the Egyptian temples show us how that people worshipped their god Isis in procession; and the chisel of Phidias, on the bas-reliefs of the Parthenon, has preserved the details of the Greek great festival in honour of Minerva, established many hundred years before Christ. First came the old men, bearing branches of the olive tree; then the young men, their heads crowned with flowers, singing hymns; children followed, dressed in their simple tunics or in their natural graces. The young Athenian ladies, who lived an almost cloistral life, came out on this occasion richly dressed, and walked singing to the notes of the flute and the lyre: the elder and more distinguished matrons also formed a part of the procession, dressed in white, and carrying the sacred baskets, covered with veils. After these came the lower orders, bearing seats and parasols, the slaves alone being forbidden to take part in it. The most important object, however, was a ship, which was moved along by hidden machinery, from the mast of which floated the peplus, or mantle of Minerva, saffron-coloured, and without sleeves, such as we see on the statues of the goddess; it was embroidered, under the direction of skilled work-women, by young virgins of the most distinguished families in Athens. The embroideries represented the various warlike episodes in heroic times. The grand object of the procession was to place the peplus on Minerva's statue, and to lay offerings of every kind at the foot of her altar. From these customs the early Christians adopted the practice of accompanying their bishop into the fields, where litanies were read, and the blessing of God implored upon their agricultural produce. Greater ceremonies were afterwards added; such as the carrying of long poles decorated with flowers, boys dressed in sacred vestments, and chanting the ancient church canticles. In the dark ages of superstition we find they advanced still further, and processions 'en chemise' were much in fashion: it was a mark of penitence which the people carried to its utmost limit during times of public calamity. Such were those in 1315, when a season of cold and rain had desolated the provinces of France: the people for five leagues round St. Denis marched in procession-the women barefoot, the men entirely naked-religiously carrying the bodies of French saints and other relics. St. Louis himself, in the year 1270, on the eve of his departure to the last crusade he shared in, and which resulted in his death, went bare-foot from the palace to the cathedral of Notre Dame, followed by the young princes his children, by the Count D'Artois, and a large number of nobles, to implore the help of heaven on his enterprise. Our king, Henry the Eighth, when a child, walked barefoot in procession to the celebrated shrine of Our Ladye of Walsingham, and presented a rich necklace as his offering. In later days he was only too glad to strip this rich chapel of all its treasures, and dissolve the monastery which had subsisted on the offerings of the pious pilgrims. That such processions became anything but religious, we may easily gather from the sermons that were preached against them: 'Alack! for pity!' says one, 'these solemn and accustomable processions be now grown into a right foul and detestable abuse, so that the most part of men and women do come forth rather to set out and shew themselves, and to pass the time with vain and unprofitable tales and merry fables, than to make general supplications and prayers to God. I will not speak of the rage and furor of these uplandish processions and gangings about, which be spent in rioting. Furthermore, the banners and badges of the cross be so irreverently handled and abused, that it is marvel God destroy us not in one day.' To pass on now to a description of the modern procession of the Fete Dieu, such as may be seen in any of the cities of Belgium, or even in more splendour in the south of France, Nismes, Avignon, or Marseilles. On rising in the morning, the whole scene is changed as by magic from the night before: the streets are festooned andgarlanded with coloured paper, flowers, and evergreens, in every direction. Linen awnings are spread across to give shelter from the darting rays of the sun. The fronts of the houses are concealed by hangings, sometimes tastefully arranged by upholsterers, but more frequently consisting of curtains, coverlids, carpets, and pieces of old tapestry, which produce a very bizarre effect. The bells are ringing in every church, and crowds are meeting at the one from which the procession is to start, or arranging themselves in the rows of chairs which are prepared in the streets; others are leaning out of the windows, whilst the sellers of cakes and bonbons make a good profit by the disposal of their tempting wares.  But the distant sound of the drum is heard, which announces the approach of the procession: first come some hundreds of men, women, and children belonging to various confreries, which answer in some degree to our sick and burial clubs, each preceded by the head man, who is adorned with numerous medals and ribbons. The children are the prettiest part: dressed in pure white muslin, their hair hanging in curls, crowned with flowers, and carrying baskets of flowers ornamented with blue ribbons. Some adopt particular characters; four boys will carry reed pens and large books in which they are diligently writing, thus personating the four evangelists; there are many virgins, one in deep black, with a long crape veil, a large black heart on her bosom, pierced with silver arrows: those boasting of the longest hair are Magdalens. The monks and secular clergy follow the people, interspersed with military bands and other music. Near the end appears, like a white cloud, a choir of girls in long veils, crowns, and tarlatan dresses-satisfying, under a pretext of devotion, the most absorbing passion of women-love of the toilette; then, lastly, comes the canopy and dais under which the priest of the highest Tank walks, carrying the Holy Sacrament, 'Corpus Christi.' This is the most striking part: silk, gold, velvet, and feathers are used in rich profusion. The splendid dresses of the cardinals or priests who surround it; the acolytes, in white, throwing up the silver censers, filling the air with a cloud of incense; the people coming out of the crowd with large baskets of poppies and other flowers to throw before it, and then all falling on their knees as it passes, while the deep voices of the clergy solemnly chant the Litany, form a very picturesque and striking scene. After the principal streets have been visited, all return to the church, which is highly decorated and illuminated: the incense ascends, the organ resounds with the full force of its pipes; trombones, ophicleides, and drums make the pillars of the nave tremble, and the host is restored to its accustomed ark on the high altar. As you walk through the streets during the week you will see at every corner, and before many porte-cocheres, little tables on which poor children spread a napkin and light some tapers, adding one or two plaster figures of the Virgin or saints; to every passer-by they cry, 'Do not forget the little chapel.' These are a remnant of the chapels which in former days were deco-rated with great pomp to serve as stations for the procession, where Mass was said iii the open air. The religious tolerance which has been pro-claimed by the French laws has much lessened the repetition of these ceremonies in Paris since 1830; and perhaps the last great display there was when the Comte d'Artois, afterwards Charles the Tenth, walked in the procession to the ancient church of St. Germain l'Auxerrois carrying a lighted taper in his hand. BIRTH OF JAMES IKing James-so learned, yet so childish; so grotesque, yet so arbitrary; so sagacious, yet so weak- 'the wisest fool in Christendom,' as Henry IV termed him-does not personally occupy a high place in the national regards; but by the accident of birth and the current of events he was certainly a personage of vast importance to these islands. To him, probably, it is owing that there is such a thing as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland among the states of Europe. This sovereign, the son of Henry Lord Darnley and Mary Queen of Scots, was born on the 19th of June 1566, in a small room in the ancient palace within Edinburgh Castle. We know how it was-namely, for security-that the queen selected Edinburgh Castle for her expected accouchement; but it is impossible to imagine by what principle of selection she chose that this event should take place in a room not above eight feet square. There, however, is the room still shown, to the wonder of everybody who sees it. The young prince was ushered into the world between nine and ten in the morning, and Sir James Melville instantly mounted horse to convey the news of the birth of an heir-apparent of Scotland, and heir-presumptive of England, to Queen Elizabeth. Darnley came at two in the afternoon to see his royal spouse and his child. 'My lord,' said Mary, 'God bias given us a son.' Partially uncovering the infant's face, site added a protest that it was his, and no other man's son. Then, turning to an English gentleman present, she said, 'This is the son who I hope shall first unite the two kingdoms of Scotland and England.' Sir William Stanley said, 'Why, madam, shall he succeed before your majesty and his father?' 'Alas!' answered Mary, 'his father has broken to me;' alluding to his joining the murderous conspiracy against Rizzio. 'Sweet madam,' said Darnley, 'is this the promise you made that, you would forget and forgive all?' have forgiven all,' said the queen. 'but will never forget. What if Fawdonside's pistol had shot? [She had felt the cold steel on her bosom.] What world have become of him and me both?' 'Madam,' said Darnley, 'these things are past.' 'Then,' said the queen, 'let them go'.  A curious circumstance, recalling one of the superstitions of the age, is related in connexion with Queen Mary's accouchement. The Countess of Athole, who was believed to possess magical gifts, lay in within the ensile at the same time as the queen. One Andrew Lundie informed John Knox that, having occasion to be in Edinburgh on business at that time. he went, up to the castle to inquire for Lady Beres, the queen's wet-nurse, and found her labouring under a very awkward kind of illness, which she explained as Lady Athole's labour pains thrown upon her by enchantment. She said, 'she was never so troubled with no bairn that ever she bare.' The infant king-for he was crowned at thirteen months old-spent his early years in Stirling Castle, under the care of the Countess of Marr, 'as to his mouth,' and that of George Buchanan, as to his education. The descendants of the Countess possessed till a recent period, and perhaps still do so, the heavy wooden cradle in which the first British monarch was rocked. A figure of it is presented on the preceding page. PASCALA mind of singular strength and keenness, united to a fragile and sensitive body, afflicted with disease and tormented by austerity, constituted Blaise Pascal. As soon as he could talk, he amazed every one by his precocious intelligence. He was an only son, and his father, a learned man, and president of the Court of Aids in Auvergne, proud of his boy, resigned his office, and went to reside in Paris, for the more effectual prosecution of his education. He had been taught something of geometry, for which. he shewed a marvellous aptitude; but his instructors, wishing to concentrate his attention on Latin and Greek, removed every book treating of mathematics out of his way. The passion was not thus to be defeated. On day Blaise was caught sitting on the floor making diagrams in charcoal, and on examination it was discovered that he had worked out several problems in Euclid for himself. No check was henceforth placed on his inclination, and he quickly became a first-rate mathematician. At sixteen he produced a treatise on Conic Sections, which was praised by Descartes, and at nineteen he devised an ingenious calculating machine. At twenty-four he experimentally verified Torricelli's conjecture that the atmosphere had weight, and gave the reason of Nature's horror of a vacuum. There is no telling what might have been the height of his success as a natural philosopher, had he not, when about twenty-five, come under overpowering religious convictions, which led him to abandon science as unworthy of the attention of an immortal creature. The inmates of the convent of Port Royal had received the Augustinian writings of Bishop Jansen with fervent approval, and had brought on themselves the violent enmity of the Jesuits. With the cause of the Port Royalists, or Jansenists, Pascal identified himself with his whole heart, and an effective and terrible ally he proved. In 1656, under the signature of Louis de Montalte, he issued his Lettres Eerites a un Provincial par un de ses Amis, in which he attacked the principles and practices of the Jesuits with a vigour of wit, sarcasm, and eloquence unanswerable. The Provincial Letters have long taken their place among the classics of universal literature by common consent. Jansenism has been defined as Calvinism in doctrine united to the rites and strictest discipline of the Church of Rome; and Pascal's life and teaching illustrate the accuracy of the definition. His opinions were Calvinistic, and his habits those of a Catholic saint of the first order of merit. His health was always wretched; his body was reduced to skin and bone, and from pain he was seldom free. Yet he wore a girdle armed with iron spikes, which he was accustomed to drive in upon his fleshless ribs as often as he felt languid or drowsy. His meals he fixed at a certain weight, and, whatever his appetite, he ate neither more nor less. All seasonings and spices he prohibited, and was never known to say of any dish, 'This is very nice.' Indeed, he strove to be unconscious of the flavour of food, and used to gulp it over to prevent his palate receiving any gratification. For the same reason he dreaded alike to love and to be loved. Toward his sister, who reverenced him as a sacred being, he assumed an artificial harshness of manner-for the express purpose, as he acknowledged, of repelling her sisterly affection. He rebuked a mother who permitted her own children to kiss her, and was annoyed when some one chanced to say that he had just seen a beautiful woman. He died in 1662, aged thirty-nine, and the examination of his body revealed a fearful spectacle. The stomach and liver were shrivelled up, and the intestines were in a gangrenous state. The brain was of unusual size and density, and, strange to say, there was no trace of sutures in the skull, except the sagittal, which was pressed open by the brain, as if for relief. The frontal suture, instead of the ordinary dovetailing which takes place in childhood, had become filled with a calculus, or non-natural deposit, which could be felt through the scalp, and obtruded on the dura mater. Of the coronal suture there was no sign. His brain was thus enclosed in a solid, unyielding ease or helmet, with a gap at the sagittal suture. Within the cranium, at the part opposite the ventricles, were two depressions filled with coagulated blood in a corrupt state, and which had produced. a gangrenous spot on the duvet mater. How Pascal, racked with such agonies from within, should have supplemented them by such afflictions from without, is one of those mysteries in which human nature is so prolific. Regarding himself as a Christian and a type of others, well might he say, as he often did, 'illness is the natural state of the Christian.' In his last years Pascal was engaged on a Defence of Christianity, and after his death the fathers of Port Royal published the materials he had accumulated for its construction, as the Pensees de Pascal. The manuscripts happily were preserved,-fragmentary, elliptical, enigmatical, interlined, blotted, and sometimes quite illegible though they were. Some years ago, M. Cousin suggested the collation of the printed text with the autograph, when the startling fact came to light that The Thoughts the world for generations had been reading as Pascal's, had been garbled in the most distressing manner by the original editors, cut down, extended, and modified according to their own notions and apprehensions of their adversaries. In 1852, a faithful version of The Thoughts was published in Paris by M. Ernest Havet, and their revival in their natural state has deepened anew our regret for the sublime genius which perished ere its prime, two hundred years ago. MAGNA CHARTAThe 19th of June 1215 remains an ever-memorable day to Englishmen, and to all nations descended from Englishmen, as that on which the Magna Charta was signed. The mean wickedness and tyranny of King John had raised nearly the whole body of his subjects in rebellion against him, and it at length appeared that he had scarcely any support but that which he derived from a band of foreign mercenaries. Appalled at the position in which he found himself, he agreed to meet the army of the barons under their elected general, FitzWalter, on Runnymead, by the Thames, near Windsor, in order to come to a pacification with them. They prepared a charter, assuring the rights and privileges of the various sections of the community, and this he felt him-self compelled to sign, though not without a secret resolution to disregard it, if possible, afterwards. It was a stage, and a great one, in the establishment of English freedom. The barons secured that there should be no liability to irregular taxation, and it was conceded that the freeman, merchants, and villains (bond labourers) should be safe from all but legally imposed penalties. As far as practicable, guarantees were exacted from the king for the fulfilment of the conditions. Viewed in contrast with the general condition of Europe at that time, the making good of such claims for the subjects seems to imply a remarkable peculiarity of character inherent in English society. With such a fact possible in the thirteenth, we are prepared for the greater struggles of the seventeenth century, and for the happy union of law and liberty which now makes England the admiration of continental nations. |