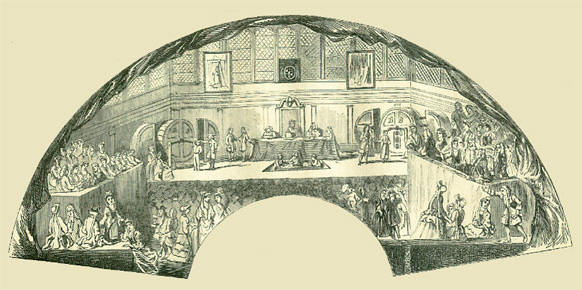

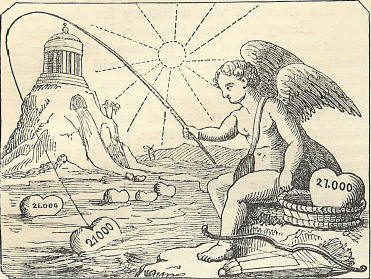

18th OctoberBorn: Pope Pius II (Æneas Silvius), 1405, Corsignano; Justus Lipsius, miscellaneous writer, 1547, Isch, Brabant; Matthew Henry, eminent divine and commentator, 1662, Broad Oak, Flintshire; Francois de Savoie, Prince Eugene, celebrated imperial general, 1663, Paris; Richard Nash (Beau Nash), celebrated master of the ceremonies at Bath, 1674, Swansea; Peter Frederik Suhm, Danish archaeologist, 1728, Copenhagen; Jean Jacques Regis Cambacébres, eminent lawyer and statesman, 1755, Montpellier; Thomas Phillips, portrait painter, 1770, Dudley, Warwickshire. Died: John Ziska, Hussite commander, 1424; Sarah Jennings, Duchess of Marlborough, 1744; Rene Antoine de Réaumur, practical philosopher and naturalist, 1757. Feast Day: St. Luke the Evangelist. St. Justin, martyr, in France, 4th century. St. Julian Sabas, hermit. St. Monan, martyr, 7th century ST. LUKEOf the companion and biographer of St. Paul, little is recorded in Scripture; but from a passage in the Epistle to the Colossians, we infer that he had been bred to the profession of a physician. In addition to this vocation, he is stated by ecclesiastical writers to have practised that of a painter, and some ancient pictures of the Virgin, still extant, are ascribed to his pencil. In consequence of this belief, which, however, rests on very uncertain foundations, St. Luke has been regarded as the patron of painters and the fine arts. He is commonly represented in a seated position, writing or painting, whilst behind him appears the head of an ox, frequently winged. This symbol has been associated with him, to quote the words of an ancient writer, 'because he devised about the presthode of Jesus Christ,' the ox or calf being the sign of a sacrifice, and St. Luke entering more largely, than the other Evangelists, into the history of the life and sufferings of our Saviour. REAUMUR AND HIS THERMOMETERRene Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur is an instance, among many, of those persons who, having devoted the greater part of their lives to scientific investigations, become known to posterity for only one, and that often a very subordinate achievement. Réaumur is now remembered almost exclusively by his thermometer: that is to say, his mode of graduating thermometers a very small thing in itself. Yet in his day he occupied ho mean place among French savans. From 1708, when he read his first paper before the Academy of Sciences, till his death on October 18, 1757, he was incessantly engaged in investigations of one kind or other. Geometrical speculations; the strength of cordage; the development of the shells of testaceous animals; the colouring matter of turquoise gemsthe manufacture of iron, steel, and porcelain artificial incubation; the imitating of the famous purple dye of the ancients; the graduation of thermometers; the reproduction of the claws of lobsters and crabs; the instincts and habits of insects all, in turn, engaged the attention of this acute and industrious man, and all furnished him with means for increasing the sum total of human knowledge. Scientific men, each in his own department, fully appreciate the value of Réaumur's labours; but to the world at large, as we have said, the thermometric scale is the only thing by which he is remembered. Almost precisely the same may be said of Fahrenheit. Had not the English persisted in using the graduation proposed by the last named individual, his name would never have become a 'household word' among us; and had hot Réaumur's scale been extensively adopted on the continent, his more elaborate investigations, buried in learned volumes, would have failed to immortalise his name. Till the early part of the last century, the scales for measuring degrees of temperature were so arbitrary, that scientific men found it difficult to understand and record each other's experiments but Fahrenheit, in 1724, had the merit of devising a definite standard of comparison. He divided the interval between freezing water and boiling water into 180 equal parts or degrees, and placed the former at 32 degrees above the zero or point of intense cold, so that the point of boiling water was denoted by 212°. It is supposed that the extreme cold observed in Iceland in 1700 furnished Fahrenheit with the minimum, or zero which he adopted in his thermometers; but such a limit to the degree of cold would he quite inadmissible now, when much lower temperatures are known to exist. Réaumur, experimenting in the same field a few years after Fahrenheit, adopted also the temperature of freezing water as his zero, and marked off 80 equal parts or degrees between that point and the temperature of boiling water. Celsius, a Swede, invented, about the year 1780, a third mode of graduation, called the Centigrade; in which he took the freezing of water as the zero point, and divided the interval between that and the point of ebullition into 100 parts or degrees. All three scales are now employed a circumstance which has proved productive of an infinite amount of confusion and error. Thus, 212° F is equal to 80° R, or 100° C; 60° F is equal to 12° R, or 17 1/9° and so on. Like the names of the constellations, it is difficult to make changes in any received system when it has become once established; and thus we shall continue to hear of Réaumur on the continent, and of Fahrenheit in England. THE LAST LOTTERY IN ENGLANDOn the 18th of October 1826, the last 'State Lottery' was drawn in England. The ceremony took place in Cooper's Hall, Basinghall Street; and although the public attraction to this last of a long series of legalised swindles was excessive, and sufficient to inconveniently crowd the hall, the lottery office keepers could not dispose of the whole of the tickets, although all means, ordinary and extraordinary, had been resorted to, as an inducement to the public to 'try their luck' for the last time. This abolition of lotteries deprived the government of a revenue equal to £250,000 or £300,000 per annum; hut it was wisely felt that the inducement to gambling held out by them was a great moral evil, helping to impoverish many, and diverting attention from the more legitimate industrial modes of money making. No one, therefore, mourned over the decease of the lottery but the lottery office keepers, then a large body of men, who rented expensive offices in all parts of England. The lottery originated among ourselves during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, when 'a very rich lottery general of money, plate, and certain sorts of merchandise' was set forth by her majesty's order, 1567 A.D. The greatest prize was estimated at £5000, of which £3000 was to he paid in cash, £700 in plate, and the remainder in 'good tapestry meet for hangings, and other covertures, and certain sorts of good linen cloth.' All the prizes were to be seen at the house of Mr. Dericke, the queen's goldsmith, in Cheapside; and a wood cut was appended to the original proclamation, in which a tempting display of gold and silver plate is profusely delineated. The lots, amounting in number to 400,000, appear to have been somewhat tardily disposed of, and the drawing did not take place until January 1568-69. On the 11th of that month, it began in a building erected for the purpose, at the west door of St. Paul's Cathedral, and continued, day and night, until the 6th of the following May. The price of the lots was 10s each, and they were occasionally subdivided into halves and quarters; and these were again subdivided for 'convenience of poorer classes.' The objects ostensibly propounded as an excuse to the government for founding this lottery, were the repair of the harbours and fortifications of the kingdom, and other public works. Great pains were taken to 'provoke the people' to adventure their money; and her majesty sent forth a second most persuasive and argumentative proclamation, in which all the advantages of the scheme were more clearly set forth; so that 'any scruple, suspition, doubt, fault, or misliking' that might occur, 'specially of those that be inclined to suspitions,' should be removed, so that all persons have 'their reasonable contentation and satisfaction.' That adventurers had 'certain doubts still, is apparent from a proclamation issued as a supplement to this from the lord mayor; in which he says, 'though the wiser sort may find cause to satisfy themselves therein, yet to the satisfaction of the scrupler sort' he deigns to more fully explain the scheme. In spite of all this, the wiser sort' did not rapidly buy shares, and the 'scrupler sort held tight their purses, so that her majesty sent a somewhat fretful mandate to the mayor of London, and the justices of Kent, Sussex, Surrey, and Hampshire, because, ' contrary to her highness' expectation,' there were many lots untaken, ' either of their negligence, or by some sinister disswasions of some not well-disposed persons: She appoints one John Johnson, gentleman, to look after her interests in the matter, and to ' procure the people as much as maybe to lay in their monies into the lots,' and orders that he ' bring report of the former doings of the principal men of every parish, and in whom any default is, that this matter hath not been so well advanced as it was looked for;' so that 'there shall not one parish escape, but they shall bring in some money into the lots.' This characteristic specimen of royal dragooning for national gambling in opposition to general desire, is a very striking commencement for a history of lottery fraud.  'The fan mount, here pictured, was exhibited at the Worcestercongress of the Archaeological Institute. The subject, printed in body colours on vellum, represents either the great lottery in 1718, when popular excitement was stimulated in so extravagant a degree, that £1,500,000 was subscribed, or that of 1714, which also presented unusual attractions. The scene, of which so spirited a representation is given on the fan, is probably in Mercer's Hall, Ironmonger Lane, Cheapside where transactions connected with lotteries usually took place. A dignified person, in black robes, is presiding; over his head is an escutcheon of St. George's cross; above are the royal arms, with the initials of Queen Anne. Many officials are in attendance, including three clerks curiously accommodated in a pit in front of the president. There is a platform, with side boxes conveniently arranged for gay gallants and fashionable ladies in the full costume of the period. The tickets are in the course of being drawn by Blue coat boys. On one side is the wheel for blanks; on the other, that for prizes the valve coverings being marked respectively B. P. These wheels, when not in use, appear to have been locked up in cases that separated into two portions when removed from the drawing apparatus, and bore the queen's initials. A precisely similar scene to that here represented, is given in the contemporary engraving, by N. Parr, in six compartments, entitled Les Divertissements de in Loterie. It was designed by J. Merchant, drawn by II Gravelot, and published by Ryland. Ave Maria Lane. Gambling, in private lotteries, was so prevalent about the time, that they were suppressed by act of parliament. In reference to the subject of fan decoration, it may here be observed, that the practice of adorning these fashionable appendages with attractive designs, was in great vogue about the middle of the last century. A gentleman, writing in the Gentleman's Magazine for May 1753, states the twelve designs upon as many fans held up before as many pretty faces, at a late celebration of the communion 'in a certain church of this metropolis,' as follows: 1. Darby and Joan; 2. Harlequin and Columbine; 3. The prodigal son, with his harlots, copied from the Rake's Progress; 4. A rural dance, with a band of music, consisting of a fiddle, a bagpipe, and a Welsh harp; 5. The taking of Portobello; 6. The solemnities of a filiation; 7. Joseph and his mistress; S. The humours of Change Alley; 9. Silenus; 10. The first interview of Isaac and Rebecca; 11. The judgment of Paris; 12. Vauxhall Gardens, with the decorations and company.' In the year following, a lottery 'for marvellous rich and beautiful armour,' was conducted for three days at the same place. In 1612, King James I, 'in special favor for the plantation of the English colonies in Virginia, granted a lottery to be held at the west end of St. Paul's; wherof one Thomas Sharplys, a tailor of London, had the chief prize, which was 4000 crowns in fair plate.' In 1619, another lottery was held ostensibly for the same purpose. Charles I. projected one in 1630, to defray the expenses of conveying water to London, after the fashion of the New River. During the Commonwealth, one was held in Grocer's Hall by the committee for lands in Ireland. It was not, however, until some years after the Restoration that lotteries became popular. They were then started under pretence of aiding the poor adherents of the crown, who had suffered in the civil wars. Gifts of plate were supposed to be made by the crown, and thus disposed of 'on the behalf of the truly loyal indigent officers.' Like other things, this speedily became a patent monopoly, was farmed by various speculators, and the lotteries were drawn in the theatres. Booksellers adopted this mode to get rid of unsaleable stock at a fancy value, mid all kinds of sharping were resorted to. ' The Royal Oak Lottery' was that which came forth with greatest eclat, and was continued to the end of the century; it met, however, with animadversion from the sensible part of the community, and formed frequently, as well as the patentees who managed it, a subject for the satirists of the day. In 1699, a lottery was proposed with a capital prize of a thousand pounds, which sum was to be won at the risk of one penny; for that was to be the price of each share, and only one share to win. The rage for speculation which characterised the people of England, in the early part of the last century, and which culminated in the South sea bubble, was favourable to all kinds of lottery speculations; hence there were 'great goes' in whole tickets, and 'little goes' in their subdivisions; speculators were protected by insurance offices; even fortune tellers were consulted about 'lucky numbers.' Thus a writer in the Spectator informs us, ' I know a well-meaning man that is very well pleased to risk his good-fortune upon the number 1711, because it is the year of our Lord. I have been told of a certain zealous dissenter, who, being a great enemy to popery, and believing that bad men are the most fortunate in this world, will lay two to one on the number 666 against any other number; because, he says, it is the number of the beast.' Guildhall was a scene of great excitement during the time of the drawing of the prizes there, and, it is a fact, that poor medical practitioners used constantly to attend, to be ready to let blood in cases when the sudden proclaiming of the fate of tickets had an overpowering effect. On the foregoing page, we have copied a very curious representation of a lottery, originally designed for a fan mount. Lotteries were not confined to money prizes, but embraced all kinds of articles. Plate and jewels were favourites; books were far from uncommon; but the strangest was a lottery for deer in Sion Park. Henry Fielding, the novelist, ridiculed the public madness in a farce produced at Drury Lane Theatre in 1731, the scene being laid in a lottery office, and the action of the drama descriptive of the wiles of office keepers, and the credulity of their victims. A whimsical pamphlet was also published about the same time, purporting to be a prospectus of 'a lottery for ladies;' by which they were to obtain, as chief prize, a husband and coachand six, for five pounds; such being the price of each share. Husbands of inferior grade, in purse and person, were put forth as second, third, or fourth rate prizes, and a lottery for wives was soon advertised on a similar plan. This was legitimate satire, as so large a variety of lotteries were started, and in spite of reason or ridicule, continued to be patronised by a gullible public. Sometimes they were turned to purposes of public utility. Thus in 1736, an act was passed for building a bridge at Westminster by lottery, consisting of 125,000 tickets at £5 each. London Bridge at that time was the only means of communication, by permanent roadway between the City and Southwark. This lottery was so far successful, that parliament sanctioned others in succession until Westminster Bridge was completed. In 1774, the brothers Adam, builders of the Adelphi Terrace and surrounding streets in the Strand, disposed of these and other premises in a lottery containing 110 prizes; the first drawn ticket entitling the holder to a prize of the value of £5000; the last drawn, to one of £25,000. Lotteries, at the close of the last century, had become established by successive acts of parliament; and, being considered as means for increasing the revenue by chancellors of our exchequer, they were conducted upon a regular business footing by contractors in town and country. All persons dabbled in chances, and shares were subdivided, that no pocket might be spared. Poor persons were kept poor by the rage for speculation, in hopes of being richer. Idle hope was not the only demoralisation produced by lotteries; robbery and suicide came therewith. The most absurd chances were paraded as traps to catch the thoughtless, and all that ingenuity could suggest in the way of advertisement and puffing, was resorted to by lottery office keepers. About 1815, they began to disseminate hand bills, with poetic, or rather rhyming, appeals to the public; and about 1820, enlisted the services of wood engravers, to make their advertisements more attractive. The subjects chosen were generally of a humorous kind, and were frequently very cleverly treated by Cruikshank and the best men of the day. They appealed, for the most part, to minds of small calibre, by depicting people of all grades expressing confidence in the lottery, a determination to try their chances, and a full reliance on 'the lucky office' which issued the handbill. 'Hone, in his Every Day Book, vol. ii, has engraved several specimens of these 'fly leaves,' now very rare, and only to be seen among the collections of the curious. We add three more examples, selected from a large assemblage, and forming curious specimens of the variety of design occasionally adopted.  It is seldom any sentimental or serious subject was attempted, but our first specimen comes in that category. This lottery was drawn on Valentine's Day; Cupid is, therefore, shown angling for hearts, each inscribed with their value, £21,000; they float toward him in a stream descending from the temple of Fortune, on a hill hi the background; and beneath is inscribed: 'Great chance! small risk! A whole ticket for only eighteen shillings! a sixteenth for only two shillings! in the lottery to be drawn on Valentine's Day; on which day, three of £2000 will be drawn in the first five minutes, which the public are sure to get for nothing!!' A whimsical notion of depicting figures of all kinds by simple dots and lines, having originated abroad, was adopted by the keepers of British lottery-offices. The following is a specimen sent oat by a large contractor named Sivewright. When possess'd of sufficient We sit at our ease; Can go where we like, And enjoy what we please. But when pockets are empty, If forced to apply To some friend for assistance, They're apt to deny. Not so with friends Sivewright, They never say nay, But lead us to Fortune The readiest way. They gallop on gaily; The fault is your own If you don't get a good share Before they're all gone.  Our third specimen is selected from a series representing the itinerant traders in the streets of London, engaged in conversation on the chances of the lottery. This is the fishwoman, who declares:  'Though a dab, I'm not scaly I like a good plaice, And I hope that good-luck will soon smile in my face; On the 14th of June, when Prizes in shoals, Will cheer up the cockles of all sorts of soals.' The English government at last felt the degradation of obtaining revenues by means of the lottery, and the last act which gave it a legal existence received the royal assent on the 9th of July 1823, and soon after 'the last' was drawn in England, as described already. Lotteries linger still upon the continent; from Hamburg we occasionally get a prospectus of some chateau and park thus to be disposed of, or some lucky scheme to be drawn; but Rome may be fairly considered as the city where they flourish best and most publicly. At certain times, the Corso is gay with lottery offices, and busy with adventurers. All persons speculate, and a large number are found among the lower grades of the clergy. The writer was present at the drawing of the lottery which took place in November 1856, in the great square termed Piazza Navona. The whole of that immense area was crammed with people, every window crowded, the houses hung with tapestries and coloured cloths, and a showy canopied stage erected at one end of the Piazza, upon which the business of drawing was conducted. As the space was so large, and the mob all eager to know fortune's behests, smaller stages were erected midway on both sides of the square, and the numbers drawn were exhibited in frames erected upon them. Bands of military music were stationed near; the pope's guard, doing duty as mounted police. The last was by no means an unnecessary precaution, for a sham quarrel was got up in the densest part of the crowd for the purpose of plunder, and some mischief done in the turmoil. Of the thousands assembled, many were priests; and all held their numbers in their hands, anxiously hoping for good fortune. It was a singular sight, and certainly not the most moral, to see people and clergy all eagerly engaged on the Sunday in gambling. |