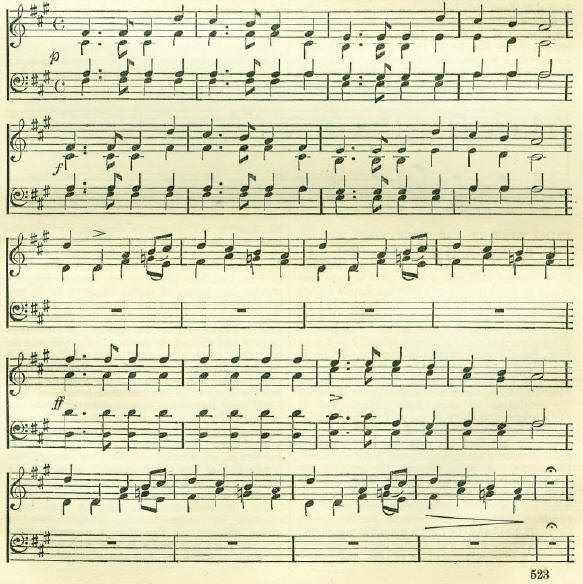

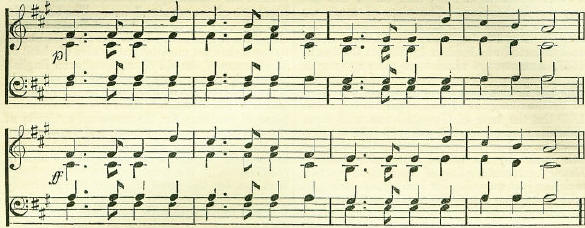

17th AprilBorn: John Ford, dramatist (baptized), 1586, Islington; Bishop Edward Stillingfleet, 1635, Cranbourn, Dorset. Died: Marino Falieri, doge of Venice, executed, 1355; Joachim Camerarius, German Protestant scholar, 1574, Leipsic; George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, 1687, Kirby Moorside; Bishop Benjamin Headley, 1761, Winchester; Dr. Benjamin Franklin, 1790, Philadelphia; James Thom, 'The Ayrshire sculptor, 1850, New York. Feast Day: St. Anicetus, Pope and martyr, 173. St. Simeon, Bishop of Ctesiphon, 341. St. Stephen, abbot of Citeaux, 1134. GEORGE VILLIERS, SECOND DUKE OF BUCKINGHAMThis nobleman, whose miserable end is described by Pope, was about six or seven years old when, on his father's murder, he succeeded to his titles and estates. During his long minority, which he passed chiefly on the Continent, his property so greatly accumulated as to have become, it is said, fifty thousand a year, equal to at least four times that sum at the present day. At the battle of Worcester, he was General of the king's horse, and, after the loss of that contest, he escaped with much difficulty. Travelling on foot through bye lanes, obtaining refreshment at cottages, and changing his dress with a woodman, he was enabled to elude the vigilance of his pursuers. At the restoration of Charles II, he was appointed to several offices of trust and honour; but such were his restless disposition and dissolute habits, that he soon lost the confidence of the king, and made a wreck of his property. 'He gave himself up,' says Burnet, 'to a monstrous course of studied immoralities.' His natural abilities, however, were considerable, and his wit and humour made him the life and admiration of the court of Charles. 'He was,' says Granger, 'the alchymist and the philosopher; the fiddler and the poet; the mimic and the statesman.' His capricious spirit and licentious habits unfitted him for the permanent leadership of any political party, nor did he generally take much interest in politics, but occasionally he devoted himself to some special measure, and would then become its principal advocate; though even on such occasions his captious, ungoverned temper often led him to give personal offence, and to infringe the rules of the House, for which he was more than once committed to the Tower. Lord Clarendon relates an amusing anecdote of him on one of these occasions, which is also a curious illustration of the manner of conducting public business at that period. 'It happened,' says the Chancellor, 'that upon the debate of the same affair, the Irish Bill, there was a conference appointed with the House of Commons, in which the Duke of Buckingham was a manager, and as they were sitting down in the Painted Chamber, which is seldom done in good order, it chanced that the Marquis of Dorchester sate next the Duke of Buckingham, between whom there was no good correspondence. The one changing his posture for his own ease, which made the station of the other more uneasy, they first endeavoured by justling to recover what they had dispossessed each other of, and afterwards fell to direct blows. In the scuffle, the Marquis, who was the lower of the two in stature, and was less active in his limbs, was deprived of his periwig, and received some rudeness, which nobody imputed to his want of courage. Indeed, he was considered as beforehand with the Duke, for he had plucked off much of his hair to compensate for the loss of his own periwig.' For this misdemeanour they were both sent to the Tower, but were liberated in a few days. The Duke of Buckingham began to build a magnificent mansion at Chiefden, in Buckingham-shire, on a lofty eminence commanding a lovely view on the banks of the Thames, where he is said to have carried on his gallantries with the notorious Countess of Shrewsbury, whose husband he killed in a duel, an account of which has already been given in this volume (page 129). Large as was his income, his profligate habits reduced him to poverty, and he died in wretchedness at Kirby Moorside, in Yorkshire, in 1687. The circumstances of his death have thus been, somewhat satirically, described by Pope in his third Epistle to Lord Bathurst: Behold what blessings wealth to life can lend, And see, what comfort it affords our end! In the worst inn's worst room, with mat half-hung, The floors of plaster, and the walls of clung, On once a flock-bed, but repaired with straw, With tape-tied curtains, never meant to draw, The George and Garter dangling from that bed Where tawdry yellow strove with dirty red, Great Villiers lies-alas how changed from him, That life of pleasure, and that soul of whim, Gallant and gay, in Cliefden's proud alcove, The bower of wanton Shrewsbury and Love; Or just as gay at council, in a ring Of mimick'd statesmen and their merry king. No wit to flatter, left of all his store! No fool to laugh at, which he valued more. There, victor of his health, of fortune, friends, And fame, this lord of useless thousands ends. The house in which the Duke died is still in existence. There is no tradition of its ever having been an inn, and it is far from being a mean habitation. It is built in the Elizabethan style, with two projecting wings; and at the time of the Duke's decease, must have been, with but one exception, the best house in the town. The room in which he expired is the best sleeping room in the house, and had then, as now, a good boarded floor. His Yorkshire place of residence was Helmsley Castle, which is about six miles from Kirby Moorside, and now a mere ruin. While hunting in the neighbourhood of Kirby, the manor of which belonged to him, he was seized with hernia and inflammation, which caused his detention and death at the above-mentioned house, then occupied, probably, by one of his tenants. So little did the house in which the Duke died really resemble Pope's description, for was his death-bed altogether without proper attendants. It so happened that just about the time of his seizure, the Earl of Arran, his kinsman, was passing through York, and hearing of the Duke's illness he hastened to him, and, on finding the condition he was in, immediately sent for a physician from York, who, with other medical men, attended on the Duke till his death. Lord Arran also sent for a Mr. Gibson, a neighbour and acquaintance of the Duke's, and apprized his family and connexions of the circumstances of his case; so that Lord Fairfax, Mr. Brian Fairfax, Mr. Gibson, and Colonel Liston, were speedily in attendance. Lord Arran also informed the Duke of his immediate danger, and, supposing him to be a Roman Catholic, proposed to send for a priest of that persuasion, but the Duke declared himself to be a member of the Church of England, and after some hesitation agreed to receive the clergyman of the parish, who offered up prayers for him, 'in which he freely joined;' and afterwards administered to him the Holy Communion. Shortly after this he became speechless, and died at eleven o'clock on the night of the 16th of April. Lord Arran ordered the body to be carried to Helmsley Castle, and, after being disbowelled and embalmed, to remain there till orders were received from the Duchess. It was subsequently taken to London, and interred in Westminster Abbey. This circumstantial account of the Duke's death is given, because Pope's has been received as historical, instead of a poetic exaggeration of the real facts of the case. Of the Duke's dissolute habits, of his unprincipled character, of his self-sacrificed health, and his ruined fortune, it is scarcely possible to speak too strongly. His possession of Helmsley Castle at his death was only nominal. In reference to his funeral, Lord Arran says: 'There is not so much as one farthing towards defraying the least expense.' Soon after his death all his property, which had long been deeply mortgaged, was sold, and did not realize sufficient to pay his debts; and dying issueless, his titles, which had been undeservedly conferred on his father and only disgraced by himself, became extinct. Indeed all the titles, nine in number, conferred by James on his favourite George Villiers and his brothers, became extinct in the next generation. Strange to say, this profligate Duke married Mary, daughter and heir of the puritan Lord Fairfax, the Parliamentary General, whom he deserted while living and left without a memento at his death. Many years after the Duke's decease, a steel seal, with his crest on it, was found in a crevice in the room wherein he died, and is still possessed by the present owner of the house; and an old parish register at Kirby contains the following curious entry: Burials; 1687, April 17th, Georges Viluas Lord dooke of bookingham. GREYSTEILThe books of the Lord Treasurer of Scotland indicate that, when James IV was at Stirling on the 17th April 1497, there was a payment 'to twa fithalaris [fiddlers] that sang Greysteil to the king, ixs.' Greysteil is the title of a metrical tale which originated at a very early period in Scotland, being a detail of the adventures of a chivalrous knight of that name. It was a favourite little book in the north throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, sold commonly at sixpence; yet, though there was an edition so late as 1711, so entirely had it lost favour during the eighteenth century, that Mr. David Laing, of Edinburgh, could find but one copy, from which to reprint the poem for the gratification of modern curiosity. We find a proof of its early popularity, not merely in its being sung to King James IV, but in another entry in the Lord Treasurer's books, as follows: 'Jan. 22, 1508, to Gray Steill, lutar, vs.;' from which it can only be inferred that one of the royal lute-players, of whom there appear to have been four or five, bore the nickname of Greysteil, in consequence of his proficiency in singing this old minstrel poem. It appears to have been deemed, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as high a compliment as could well be paid to a gallant warrior, to call him Greysteil. For example, James V. in boyhood bestowed this pet name upon Archibald Douglas, of Kilspindie; and even when the Douglas was under banishment, and approaching the king in a kind of disguise for forgiveness, 'Yonder is surely my Greysteil,' exclaimed the monarch, pleased to recall the association of his early clays. Another personage on whom the appellation was bestowed was Alexander, sixth Earl of Eglintoun, direct ancestor of the present Earl. A break in the succession (for Earl Alexander was, paternally, a Seton, not a Montgomery) had introduced a difficulty about the descent of both the titles and estates of the family, and the lordship of Kilwinning was actually given away to another by Act of Parliament, in 1612. In a family memoir we are told, Alexander was not a man tamely to submit to such injustice, and the mode which he adopted to procure redress was characteristic. He had repeatedly remonstrated, but in vain. Irritated by the delay on the part of the crown to recognise his right to the earldom, and feeling further aggrieved by the more material interference with his barony of Kilwinning, he waited personally on the Earl of Somerset, the King's favourite, with whom he supposed the matter mainly rested. He gave the favourite to understand that, as a peer of the realm, he was entitled to have his claims heard and justice done him, and that though but little skilled in the subtleties of law and the niceties of court etiquette, he knew the use of his sword. From his conduct in this affair, and his general readiness with his sword, the Earl acquired the sobriquet of Greysteil, by which he is still known in family tradition.' It will probably be a surprise to most of our readers that the tune of old called Greysteil, and probably the same which was sung to James IV of Scotland in 1497, still exists, and can now be forthcoming. The piece of music we refer to is included, under the name Grey-steil, in Ane Playing Booke for the Lute, noted and collected at Aberdeen by Robert Gordon in 1627,' a manuscript which some years ago was in the possession of George Chalmers, the historian. The airs in this book being in tablature, a form of notation long out of use, it was not till about 1840 that the tune of Greysteil was with some difficulty read off from it, and put into modern notation, and so communicated to the writer of this notice by his valued friend Mr. William Dauney, advocate, editor of the ancient Scottish melodies just quoted. Mr. Dauney, in sending it, said, 'I have no doubt that it is in substance the air referred to in the Lord Treasurer's accounts. The ballad or poem to which it had been chanted, was most probably the popular romance of that name, which you will find in Mr. Laing's Early Metrical Tales, and of which he says in the preface that, 'along with the poems of Sir David Lyndsey, and the histories of Robert Bruce and of Sir William Wallace, it formed the standard production of the vernacular literature of the country.' .... The tune,' Mr. Dauney goes on to say, is not Scottish in its structure or character; but it bears a resemblance to the somewhat monotonous species of chant to which some of the old Spanish and even English historical ballads were sung. In this respect it is suitable to the subject of the old romance, which is not Scottish. There is a serviceable piece of evidence for the presumed antiquity of the air, in the fact that a satirical Scotch poem on the unfortunate Earl of Argyle, dated 1686, bears on it, appointed to be sung to the tune of old Greysteil.' We must, however, acknowledge that, but for this proof of poetry being actually sung to Old Greysteil, we should have been disposed to think that the tune here printed was only presented by the luters as a sort of prelude or refrain to their chanting of the metrical romance in question. The abruptness of the end is very remarkable. The tune of Greysteil, for certain as old as 1627, and presumed to be traditional from at least 1497, is as follows:   When on the subject of so early a piece of Scotch music, it may not be inappropriate to advert to another specimen, which we can set forth as originally printed in 1588, being the oldest piece in print as far as we know. It is only a simple little lilt, designed for a homely dance, but still, from its comparative certain antiquity, is well worthy of preservation. Mr. Douce has transferred it into his Illustrations of Shakespeare, from the book in which it originally appeared, a volume styled Orehesograpitie, professedly by Thionot Arbeau (in reality by a monk named Jean Tabouret), printed at Lengres in the year above mentioned. He calls it a branle or brawl, 'which was performed by several persons uniting hands in a circle and giving each other continual shakes, the steps changing with the tune. It usually consisted of three pas and a pied: joint to the time of four strokes of the bow; which being repeated, was termed a double brawl. With this dance balls were usually opened.' The copy given in the original work being in notation scarcely intelligible to a modern musician, we have had it read off and harmonised as follows:  - BRING THEM IN AND KEEP THEM AWAKEOn the 17th April 1725, John Rudge bequeathed to the parish of Trysull, in Stafford-shire, twenty shillings a year, that a poor man might be employed to go about the church during sermon and keep the people awake; also to keep dogs out of church. A bequest by Richard Dovey, of Farmcote, dated in 1659, had in view the payment of eight shillings annually to a poor man, for the performance of the same duties in the church of Claverley, Shropshire. In the parishes of Chislet, Kent, and Peterchurch, Herefordshire, there are similar provisions for the exclusion of dogs from church, and at Wolverhampton there is one of five shillings for keeping boys quiet in time of service. We do not find any very early regulations made to secure the observance of festivals among Christians. A solicitude on the subject becomes apparent in the middle ages. Early in the thirteenth century, we meet with a document of a curious nature, the principal object of which is to awaken a reverence for the Lord's day. It professes to be 'a mandate which fell from heaven, and was found on the altar of St. Simon, on Mount Golgotha, in Jerusalem,' and humbly taken by the patriarch, and the Archbishop Akarias, after that for three days and three nights the people, with their pastors, had lain prostrate on the ground, imploring the mercy of God.' A copy of it was brought to England by Eustachius, abbot of Hay; who, on his return from the Holy Land, preached from city to city against the custom of buying and selling on the Sunday. 'If you do not obey this command,' says this celestial message, 'verily, I say unto you, that I will not send you any other commands by another letter, but I will open the heavens, and instead of rain I will pour down upon you stones and wood, and hot water by night; so that ye shall not be able to guard against it, but I will destroy all the wicked men. This I say unto you; ye shall die the death, on account of the holy day of the Lord; and of the other festivals of my saints which ye do not keep, I will send upon you wild beasts to devour you,' &c. Yet the sacredness of the day had been attested by extraordinary interpositions of divine power. At Beverley, a carpenter who was making a peg, and a weaver who continued to work at his web after three o'clock on the Saturday, were severally struck with palsy. In Nasurta, a village which belonged to one Roger Arundel, a man who had baked a cake in the ashes after the same hour, found it bleed when he tried to eat it on Sunday, and a miller who continued to work his mill was arrested by the blood which flowed from between the stones, in such quantity as to prevent their working; while in some places, not named, in Lincolnshire, bread put by a woman into a hot oven after the forbidden hour, remained unbaked on the Monday; when another piece, which by the advice of her husband she put away in a cloth, because the ninth hour was past, she found baked on the morrow.-(Notes to Feasts and Fasts, by E. V. Neale.) Leland presents evidence of the same kind of feeling in a story told of Richard de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, by annalists, to this effect. In the year 1260, a Jew of Tewkesbury fell into a sink on the Sabbath, and out of reverence for the day, would not suffer himself to be drawn out; the earl, out of reverence for the Sunday, would not permit him to be drawn out the next day, and between the two he died. By the 5th and 6th Edward VI, and by 1st Elizabeth, it was provided, that every inhabitant of the realm or dominion shall diligently and faithfully, having no lawful or reasonable excuse to be absent, endeavour themselves to their parish church or chapel accustomed; or, upon reasonable let, to some usual place where common prayer shall be used,-on Sundays and holidays, -upon penalty of forfeiting for every non-attendance twelve pence, to be levied by the churchwardens to the use of the poor. But the application of these provisions to the attendance upon other holidays than Sundays, seems to have been soon dropped. The statute of James I, re-enacting the penalty of one shilling for default in attendance at church, is limited to Sundays; and the latter day alone is mentioned in the Acts of William and Mary, and George III, by which exceptions in favour of dissenters from the Church of England were introduced. As the statute of James applied solely to Sundays, there was no civil punishment left for this neglect; though it remained punishable, under the 5th and 6th of Edward VI, by ecclesiastical censures. Mr. Vansittart Neale, in his Feasts and Fasts, however, cites several cases which appear to settle that the ecclesiastical courts had not the power to compel any person to attend his parish church, because they have no right to decide the bounds of parishes. There were, however, from time to time, suits commenced against individuals for this neglect of attendance at church; these actions being generally instigated by personal motives rather than with religious feeling. Professor Amos, in his Treatise on Sir Matthew Hale's History of the Pleas of the Crown, states the following cases: In the year 1817, at the Spring Assizes for Bedford, Sir Montague Burgoyne was prosecuted for having been absent from his parish church for several months; when the action was defeated by proof of the defendant having been indisposed. And in the Report of Prison Inspectors to the House of Lords, in 1841, it appeared, that in1830, ten persons were in prison for recusancy in not attending their parish churches. A mother was prosecuted by her own son.' These enactments remained in our Statute-book, until, in common with many other penal and disabling laws in regard to religious opinions, they were swept away by the statute 9th and 10th Viet., c. 59. It also appears that in old times many individuals considered it their duty to set aside part of their worldly wealth for keeping the congregation awake. Some curious provisions were made for this purpose. At Acton church in Cheshire, about five and twenty years ago, one of the churchwardens or the apparitor used to go round the church during service, with a long wand in his hand; and if any of the congregation were asleep, they were instantly awoke by a tap on the head. At Dunchurch, a similar custom existed: a person bearing a stout wand, shaped liked a hay fork at the end, stepped stealthily up and down the nave and aisle, and, whenever he saw an individual asleep, he touched him so effectually that the spell was broken; this being sometimes done by fitting the fork to the nape of the neck. We read of the beadle in another church, going round the edifice during service, carrying a long staff, at one end of which was a fox's brush, and at the other a knob; with the former he gently tickled the faces of the female sleepers, while on the heads of their male compeers he bestowed with the knob a sensible rap. In some parishes, persons were regularly appointed to whip dogs out of church; and 'dog-whipping' is a charge in some sexton's accounts to the present day. |