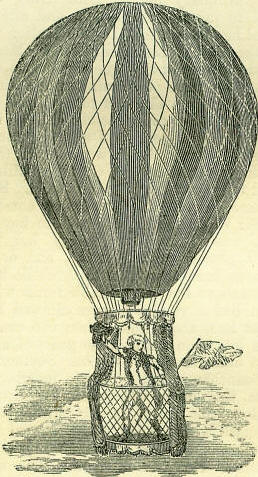

15th SeptemberBorn: Jean Sylvain Bailly, distinguished astronomer, 1736, Paris; James Fenimore Cooper, American novelist, 1789, Burlington, New Jersey; John, Lord Campbell, chancellor of England, 1779, Cupar-in-Fife. Died: Philip of Austria, father of Charles V, 1506 Sir Thomas Overbury, poisoned in the Tower, 1613 Lady Arabella Stuart, 1615; Richard Boyle, Earl of Cork, eminent statesman, 1643, Youghal; Sidney, Earl of Godolphin, premier to Queen Anne, 1712, St. Albans; Abbe Terrasson, translator of Diodorus Siculus, 1750 General Lazarus Roche, French commander, 1797, Wetzlar; William Huskisson, distinguished politician and economist, killed at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, 1830; I. K. Brunel, eminent civil engineer, 1859, Westminster. Feast Day: St. Nicomedes, martyr, about 90. St. Nicetas, martyr, 4th century. St. John the Dwarf, anchoret of Scotch St. Aper or Evre, bishop and confessor, 5th century. St. Aicard or Achart, abbot and confessor, about 687. ROMANCE OF THE LADY ARABELLAAlthough Lady Arabella Stuart plays no very prominent part amid the public characters of her time, her history presents a series of romantic incidents and disasters, scarcely surpassed even by those of her celebrated relative, Mary Queen of Scots. She was the daughter of Charles Stuart, Earl of Lennox, younger brother of Lord Darnley, and stood thus next in succession to the crown, after her cousin, James VI, through their common ancestor Margaret Tudor, sister of Henry VIII, and grandmother, by her second marriage with the Earl of Angus, to Lord Darnley. Brought up in England, Arabella excited the watchful care and jealousy of Elizabeth, who, on the king of Scotland proposing to marry her to Lord Esmé Stuart, interposed to prevent the match, and afterwards imprisoned her, on hearing of her intention to wed a son of the Earl of Northumberland. Meantime she formed the subject of eager aspirations on the continent, the pope entertaining the idea of uniting her to some Catholic prince, and setting her up as the legitimate heir to the English throne. Among her suitors appear the Duke of Parma, and the Prince of Farnese; but it would seem that the idea which prevailed abroad of her predilections for the old religion was quite unfounded. Shortly after the accession of James I, a clumsy conspiracy, in which Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have been concerned, was formed for raising her to the throne. It proved quite abortive, and does not seem to have been shared in by Arabella herself, who continued to live on amicable terms with the court, and had a yearly pension allowed her by James. At last, about 1609, when she could not have been less than thirty-three years of age, she formed an attachment to William Seymour, son of Lord Beauchamp, and a private marriage took place. On this being discovered, Seymour was committed to the Tower for his presumption in allying himself with a member of the royal family, and his wife was detained a prisoner in the house of Sir Thomas Parry, in Lambeth. The wedded pair, nevertheless, managed to correspond with each other; whereupon, it was resolved to remove Arabella to a distance, and place her under the custody of the bishop of Durham. Her northward journey commenced, but, either feeling or affecting indisposition, she advanced no further than High-gate, where she was allowed to remain under surveillance, in the house of Mr. Conyers. A plot to effect her escape was now concocted on the part of herself and Seymour. The subsequent mishaps of this ill-starred couple read like a tale of romance. One afternoon she contrived to obtain leave from her female guardian at Highgate to pay a visit to her husband, on the plea of seeing him for the last time. She then disguised herself in man's clothes, with a doublet, boots, and rapier, and proceeded with a gentleman named Markham to a little inn, where they obtained horses. On arriving there, she looked so pale and exhausted that the ostler who held her stirrup, declared the gentleman would never hold out to London. The ride, however, revived her, and she reached Blackwall in safety, where she found a boat waiting. Mr. Seymour, who was to have joined her here, had not yet arrived, and, in opposition to her earnest entreaties, her attendants insisted on pushing off, saying that he would be sure to follow them. They then crossed over towards Woolwich, pulled down from thence to Gravesend, and afterwards, by the promise of double fare, induced the rowers to take them to Lee, which they reached just as day was breaking. A French vessel was descried lying at anchor for them about a mile beyond, and Arabella, who again wished to abide here her husband's arrival, was forced on board by the importunity of her followers. In the meantime, Seymour, disguised in a wig and black cloak, had walked out of his lodgings at the west door of the Tower, and followed a cart which was returning after having deposited a load of wood. He proceeded by the Tower wharf to the iron gate, and finding a boat there lying for him, dropped down the river to Lee, with an attendant. Here he found the French ship gone; but, imagining that a vessel which he saw under sail was the craft in question, he hired a fisherman for twenty shillings to convey him thither. The disappointment of the luckless husband may be imagined when he discovered that this was not the ship he was in quest of. He then made for another, which proved to be from Newcastle, and an offer of £40 induced the master to convey Seymour to Calais, from which he proceeded safely into Flanders. The vessel conveying Arabella was overtaken off Calais harbour by a pink despatched by the English authorities on hearing of her flight, and she was conveyed back to London, subjected to an examination, and committed to the Tower. She professed great indifference to her fate, and only expressed anxiety for the safety of her husband. To the end of her days Arabella Stuart remained a prisoner. She died in confinement in 1615, and rumours were circulated of her having fallen a victim to poison; but these would seem to have been wholly unwarranted. Such unmerited misfortunes did her near relationship to the crown entail. Her husband afterwards procured his pardon, distinguished himself by his loyalty to Charles I during the civil wars, and, surviving the Restoration, was invested by Charles II with the dukedom of Somerset, the forfeited title of his ancestor, the Protector. FIRST BALLOON ASCENTS IN BRITAINThe inventions and discoveries ultimately proving least beneficial to mankind, have generally been received with greater warmth and enthusiasm than those of a more useful character. The aeronautical experiments of the Montgolfiers and others, in France, created an immense excitement, which. soon found its way across the Channel to the shores of England. Horace Walpole, writing at the close of 1783, says: 'Balloons occupy senators, philosophers, ladies, everybody.' While some entirely disbelieved the accounts of men, floating, as it were, in the regions of upper air, others indulged in the wildest speculations. The author of a poem, entitled The Air Balloon, or Flying Mortal, published early in 1784, exclaims: How few the worldly evils now I dread, No more confined this narrow earth to tread! Should fire or water spread destruction drear, Or earthquake shake this sublunary sphere, In air-balloon to distant realms I fly, And leave the creeping world to sink and die. Besides doubt and wonder, an unpleasant feeling of insecurity prevailed over England at the time. The balloon was a French invention: might it not be used as a means of invasion by the natural enemies of the British race! A caricature, published in 1784, is entitled Montgolfier in the Clouds, constructing Air Balloons for the Grande Monarque. In this, the French inventor is represented blowing soap-bubbles, and saying: O by Gar, dis be de grand invention. Dis will immortalise my king, my country, and myself. We will declare the war against our enimie; we will made des English quake, by Gar. We will inspect their camp, we will intercept their fleet, and we will set fire to their dock-yards, and, by Gar, we will take Gibraltar, in de air-balloon; and when we have conquer de English, den we conquer de other countrie, and make them all colonie to de Grande Monarque.  Several small balloons had been sent up from various parts of England; but no person, adventurous enough to explore the realms of air, had ascended, till Vincent Lunardi, a youthful attache' of the Neapolitan embassy, made the first ascent in England from the Artillery Ground, at Moorfields, September 15, 1784. It was Lunardi's original intention to ascend from the garden of Chelsea Hospital, having acquired permission to do so; but the permission was subsequently rescinded, on account of a riot caused by another balloon adventurer, a Frenchman named De Moret. This man proposed to ascend from a tea-garden, in the Five-fields, a place now known by the general term of Belgravia. His balloon seems, from an engraving of the period, to have resembled one of the large, old-fashioned, wooden summer-houses still to be seen in suburban gardens; and the car was provided with wheels, so that it could, if required, be used as a travelling-carriage! Whether he ever intended to attempt an ascension in such an unwieldy machine, has never been clearly ascertained. The balloon, such as it was, was constructed on the Montgolfier, or fire, principle-that is to say, the ascending agent was air rarefied by the application of artificial heat. De Moret, having collected a considerable sum of money, was preparing for an ascent on the 10th of August 1784, when his machine caught fire, and was burned, the unruly mob revenging their disappointment by destroying the adjoining property. The adventurer, however, made a timely escape, and a caricature of the day represents him flying off to Ostend with a bag of British guineas, leaving the Stockwell Ghost, the Bottle Conjuror, Elizabeth Canning, Mary Toft, and other cheats, enveloped in the smoke of his burning balloon. The authorities, being apprehensive that, in case of failure, Chelsea Hospital might be destroyed in a similar riot, rescinded their permission; but Lunardi was, eventually, accommodated with the use of the Artillery Ground, the members of the City Artillery Company being under arms, to protect their property. When the eventful day arrived, Moorfields, then an open space of ground, was thronged by a dense mob of spectators; such crowd had never previously been collected in London. As the morning hours wore away, silent expectation was followed by impatient clamour, soon succeeded by yells of angry threatenings, to be in a moment changed to loud acclamations of applause, as the balloon rose majestically into the air. Lunardi himself said: The effect was that of a miracle on the multitude which surrounded the place, and they passed from incredulity and menace into the most extravagant expressions of approbation and joy. Lunardi first touched earth in a field at North Mimms; after lightening the balloon, he again rose in the air, and finally descended in the parish of Standon, near Ware, in Hertfordshire. Some labourers, who were working close by, were so frightened at the balloon, that no promises of reward would induce them to approach it; not even when a young woman had courageously set the example by taking hold of a cord, which the aěronaut had thrown out. The adventurer came down from the clouds to find himself the hero of the day. He was presented at court, and at once became the fashion; wigs, coats, hats, and bonnets were named after him; and a very popular bow of bright scarlet ribbons, that had previously been called Gibraltar, from the heroic defence of that fortress, was now termed the Lunardi. By exhibiting his balloon at the Pantheon, he soon gained a large sum of money; and the popular applause might readily have turned the head of a less vain person than the impulsive Italian. Mr. Lunardi's publications exhibit him as a vain excitable young man, utterly carried away by the singularity of his position. He tells us how a woman dropped down dead through fright, caused by beholding his wondrous apparition in the air; but, on the other hand, he saved a man's life, for a jury brought in a verdict of Not guilty on a notorious highwayman, that they might rush out of court to witness the balloon. When Lunardi arose, a cabinet council was engaged on most important state deliberations; but the king said: 'My lords, we shall have an opportunity of discussing this question at another time, but we may never again see poor Lunardi; so let us adjourn the council, and observe the balloon!' Ignorance, combined with vanity, led Lunardi into some strange assertions. He professed to be able to lower his balloon, at pleasure, by using a kind of oar. When he subsequently ascended at Edinburgh, he affirmed that, at the height of 1100 feet, he saw the city of Glasgow, and also the town of Paisley, which are, at least, forty miles distant, with a hilly country between. The following paragraph from the General Advertiser of September 24, 1784, has a sly reference to these and the like allegations. As several of our correspondents seem to disbelieve that part of Mr. Lunardi's tale, wherein be states that he saw the neck of a quart bottle four miles' distance, all we can inform them on the subject is, that Mr. Lunardi was above lying. Lunardi's success was, in all probability, due to the suggestions of another, rather than to his own scientific acquirements. His original intention was to have used a Montgolfier or fire balloon, the inherent perils of which would almost imperatively forbid a successful result. But the celebrated chemist, Dr. George Fordyce, informed him of the buoyant nature of hydrogen gas, with the mode of its manufacture; and to this information Lunardi's successful ascents may be attributed. Three days before Lunardi ascended, Mr. Sadler made an ineffectual attempt at Shotover Hill, near Oxford, but was defeated, by using a balloon on the Montgolfier principle. It is generally supposed that Lunardi was the first person who ascended by means of a balloon in Great Britain, but he certainly was not. A very poor man, named James Tytler, who then lived in Edinburgh, supporting himself and family in the humblest style of garret or cottage life by the exercise of his pen, had this honour. He had effected an ascent at Edinburgh on the 27th of August 1784, just nineteen days previous to Lunardi. Tytler's ascent, however, was almost a failure, by his employing the dangerous and unmanageable Montgolfier principle. After several ineffectual attempts, Tytler, finding that he could not carry up his fire-stove with him, determined, in the maddening desperation of disappointment, to go without this his sole sustaining power. Jumping into his car, which was no other than a common crate used for packing earthenware, he and the balloon ascended from Comely Garden, and immediately afterwards fell in the Restalrig Road. For a wonder, Tytler was uninjured; and though he did not reach a greater altitude than three hundred feet, nor traverse a greater distance than half a mile, yet his name must ever be mentioned as that of the first Briton who ascended with a balloon, and the first man who ascended in Britain. Tytler was the son of a clergyman of the Church of Scotland, and had been educated as a surgeon; but being of an eccentric and erratic genius, he adopted literature as a profession, and was the principal editor of the first edition of the Encyclopredia Britannica. Becoming embroiled in politics, he published a handbill of a seditious tendency, and consequently was compelled to seek a refuge in America, where he died in 1805, after conducting a newspaper at Salem, in New England, for several years. A prophet acquires little honour in his own country. While poor Tytler was being overwhelmed by the coarse jeers of his compatriots, Lunardi came to Edinburgh in 1785, and was received with the utmost enthusiasm. His first ascent in Scotland was made from the garden of Heriot's Hospital, and the cause down at Ceres, near Cupar, in Fife. The clergyman of the parish, who witnessed. his descent, writing to an Edinburgh newspaper, says: As it [the balloon] drew near the earth, and sailed along with a kind. of awful grandeur and majesty, the sight gave much plea-sure to such as knew what it was, but terribly alarmed such as were unacquainted with the nature of this celestial vehicle. A writer in the Glasgow Advertiser thus describes the sensation caused by Lunardi's first ascent from that city: Many were amazingly affected. Some shed tears, and some fainted, while others insisted that he was in compact with the devil, and ought to be looked upon as a man reprobated by the Almighty. The hospitality and attention Lunardi received in Scotland seems to have completely turned his weak head. When publicly entertained in Edinburgh, and asked to propose a toast, he gave, 'Lunardi, the favourite of the ladies!' to the infinite amusement of the assemblage. His last appearance in End land, previous to his return to Italy, was as the inventor of what he termed a water-balloon, a sort of tin life-buoy, with which he made several excursions on the Thames. OPENING OF THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER RAILWAYOne of the 'red-letter' days in the history of railways, a day that stamped the railway-system as a triumphant success, was marked by a catastrophe which threw gloom over an event in other ways most satisfactory. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the first on which the powers of the steam-locomotive for purposes of traction were fully established. On the Stockton and Darlington line, formed a few years earlier, traction by animal power, by fixed. engines, and by locomotives, had all been tried; and the experience thereby obtained had determined George Stephenson to recommend the locomotive system for adoption on the Liverpool and Manchester line. When this railway was in progress, in 1829, the directors offered a premium of £500 for the best form of locomotive, to be determined by public competition, on conditions very clearly laid down. In October of that year the contest took place; and Mr. Robert Stephenson's locomotive, Rocket, carried off the prize against Mr. Hackworth's Sanspareil, and Messrs Braithwaite and Ericsson's Novelty. A period of eleven months then elapsed for the finishing of the railway and the manufacture of a store of locomotives and carriages. On the 15th of September 1830, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was opened with great ceremony. The Duke of Wellington, Sir Robert Peel, Mr. Huskisson, and many other distinguished persons were invited. Eight locomotives, all built by Robert Stephenson, on the model of the Rocket, took part in the procession. The Northumbrian took the lead, drawing a splendid carriage, in which the duke, Sir Robert, and other distinguished visitors were seated. Each of the other locomotives drew four carriages; and the whole of the twenty-nine carriages conveyed six hundred persons. They formed eight distinct trains; the first one, with the more distinguished guests, having one line of rails to itself; and the other seven following each other on the second line. The procession, which started from Liverpool about eleven o'clock, was an exceedingly brilliant one, with the aid of flags, music, &c. and the sides of the railway were lined with thousands of enthusiastic spectators. The trains went on past Wavertree Station, Olive Mount Cutting, Rainhill Bridge, the Sutton Incline, and the Sankey Viaduct, to Parkhurst. Here it was (seventeen miles from Liverpool) that the trains stopped to enable the locomotives to take in water; and here it was that the deplorable accident occurred, which threw a cloud over the brilliant scene. In order to afford the Duke of Wellington an opportunity of seeing the other parts of the procession, it was determined that the seven locomotives, with their trains, should pass him; his carriage, with the Northumbrian, being for a while stationary. Several gentlemen alighted from the carriages while the locomotives were taking in water. Mr. Huskisson, who was one of them, went up to shake hands with the duke and while they were together, the Rocket passed rapidly on the other line. The unfortunate gentleman, who happened to be in a weak state of health, became flurried, and ran to and fro in doubt as to the best means of escaping danger. The engine-driver endeavoured to stop the train in time, but without success; and Mr. Huskisson, unable to escape, was knocked down by the Rocket, the wheels of which went over his leg and thigh. The same locomotive which had triumphed at the competition, now caused the death of the statesman. The directors deemed it necessary to complete the remainder of the journey to Manchester, as a means of showing that the railway, in all its engineering elements, was thoroughly successful but it was a sad. procession for those who thought of the wounded statesman. He expired that same evening. Mr. Huskisson was born March 11, 1770. In 1790, he first entered government service, as private secretary to the British ambassador at Paris. In 1793, he was appointed to an office for managing the claims of French emigrants in 1795, Under Secretary of State for War and the Colonies; in 1804, Secretary of the Treasury; and in 1807, he resumed the same office, after a short period in opposition. In 1814, he was made Chief Commissioner of Woods and Forests; in 1823, President of the Board of Trade and Treasurer of the Navy; and in 1829, Secretary of State for the Colonies. He had thus, during about forty years, rather a varied experience of official life. Mr. Huskisson, in the House of Commons, was not a speaker of any great eloquence; but he is favourably remembered as having advocated a free-trade policy at a time when such policy had few advocates in parliament. |