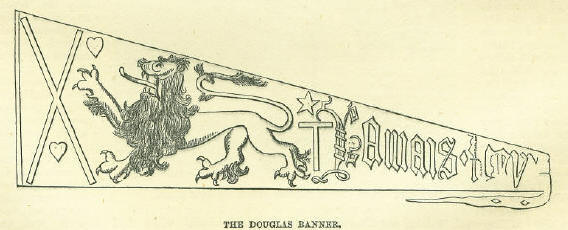

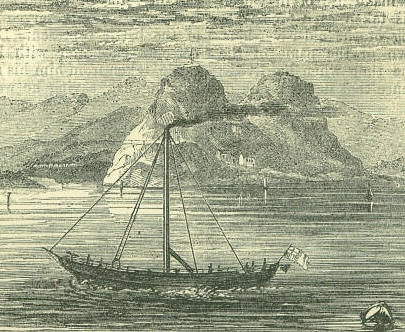

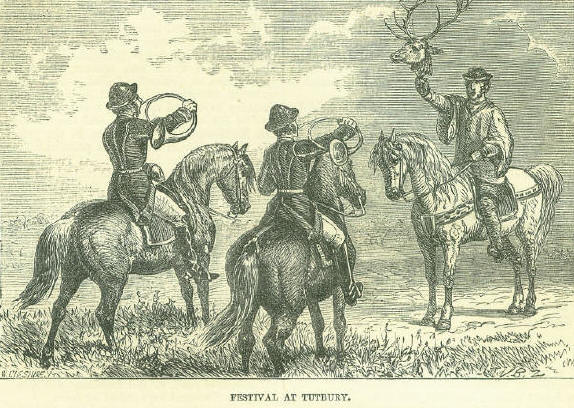

15th AugustBorn: Robert Blake, celebrated admiral, 1599, Bridge-water; Gilles Menage, miscellaneous writer (Dictionnaire Etymologique), 1613, Angers; Frederick William I of Prussia, 1688; Napoleon Bonaparte, French emperor, 1769, Ajaccio, Prance; Sir Walter Scott, poet and novelist, 1771, Edinburgh; Thomas de Quincey, author of Confessions of an English Opium Eater, 1785, Manchester. Died: Honorius, Roman emperor, 423; St. Stephen, first king of Hungary, 1038, Buda; Alexius Comnenus, Greek emperor, 1118; Philippa, queen of Edward III of England, 1369; Gerard Noodt, distinguished jurist, 1725, Leyden; Joseph Miller, comedian, 1738; Nicolas Hubert de Mongault, translator of Cicero's Letters, 1746, Paris; Dr. Thomas Shaw, traveller, 1751, Oxford; Thomas Tyrwhitt, editor of Chaucer, 1786; Dr. Herbert Mayo, eminent physiologist, 1852, Bad-Weilbaeh, near Mayence. Feast Day: The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. St. Alipius, bishop and confessor, 5th century. St. Maccartin, Aid or Aed, bishop and confessor in Ireland, 506. St. Arnoul or Arnulphus, confessor and bishop of Soissons,1087. NAPOLEON BONAPARTEAfter all that has been said and written on the subject of Napoleon Bonaparte, the conclusion is forced upon us, that he had few of the elements in his composition which go to make up the character of a true hero. Of unbounded ambition, perfectly unscrupulous as to the means by which he might accomplish his ends, and tinged throughout by an utter selfishness and regardlessness of others, we can deem him no more entitled to a real and intelligent admiration, than a previous occupant of the French throne, Louis XIV, brilliant in many respects though the reigns of both these men undoubtedly were. That the first Napoleon was in many ways a benefactor to France, cannot reasonably be denied. By his military and administrative abilities he raised himself to supreme power at a time when the country was emerging from the lawlessness and terrorism to which she had been subjected after the death of Louis XVI. The divided and profligate government of the Directorate had succeeded the anarchy and violence of the leaders of the Convention. Some powerful hand was required as a dictator to hold the reins of state, and arrange in a harmonious and well-adjusted train the various jarring and unstable systems of government. Had he conducted himself with the same prudence as his nephew, the present emperor, he might have died absolute sovereign of France, and the history of that country been written without the narrative of the Restoration of the Bourbons, the Three Days of July 1830, and the Revolution of February 1848. But vaulting ambition with him overleaped itself, and his impetuous self-willed nature, or what he himself used to consider his destiny, drove him headlong to his ruin. Regardless of the warnings addressed to him by the most sagacious of his counsellors, contemptuously defiant of the coalitions formed to impede his progress, and careless, lastly, of the odium which his tyrannical sway in the end excited among his own subjects, he found himself at length left utterly destitute of resources, and obliged to submit to such terms as his enemies chose to impose. His career presents one of the most melancholy and impressive lessons that history affords. And yet how eagerly would a large portion of the French nation revert to a policy which, in his hands, overwhelmed it only with vexation and disaster! Napoleon's character may be contemplated in three phases-as a statesman, as a commander, and as a private individual. In the first of these capacities, he displayed, as regards France, much that was worthy of commendation in point of political and social reform. A vigorous administration of the laws, a simplification of legal ordinances and forms, a wise and tolerating system in religious matters, many important and judicious sanitary measures, the embellishment of the capital, and patronage afforded to art and science, must all be allowed to have been distinguishing attributes of his sway. But how little did he understand the art of conciliating and securing the allegiance of the countries which he had conquered! A total ignoring of all national predilections and tendencies seems to have been here habitually practised by him, and nowhere was this more conspicuous than in his treatment of Germany. That system of centralization, by which he sought to render Paris the capital of a vast empire, at the expense of the dignity and treasures of other cities and kingdoms, might flatter very sensibly the national vanity of France, but was certain, at the same time, to exasperate the degraded and plundered countries beyond all hopes of forgiveness. And the outrages which he tacitly permitted his troops to exercise on the unfortunate inhabitants, argue ill for the solidity or wisdom of his views as a governor or statesman. The military genius of Bonaparte has been, and still is, a fruitful theme for discussion. In the early part of his career, he achieved such successes as rendered his name a terror to Europe, and gained for him a prestige which a series of continuous and overwhelming defeats in the latter period of his history was unable to destroy. But in the game of war, results alone can form the criterion, and the victories of Marengo, of Austerlitz, and of Wagram can scarcely be admitted in compensation for the blunders of the Russian campaign and the overthrow at Waterloo. One qualification, however, of a great general, the capacity of recognising and rewarding merit, in whatever position it might be found, was eminently conspicuous in Napoleon. Favouritism, and the influence of rank or fortune, were almost entirely unknown in his army. Few of his generals could boast much of family descent, and the circumstance that bravery and military talent were certain to receive their due reward in promotion or otherwise, gave every man a personal interest in the triumph of the emperor's arms. An inquiry into the personal character of Bonaparte exhibits him perhaps in a still less favourable sight than that in which we have hitherto been considering him. Of a cold-blooded and impassible temperament, and engrossed exclusively by the master-passion, ambition, he betrayed no tendencies towards any of those aberrations by which the characters of so many other great men have been stained. But the very cause which kept his moral purity inviolate, rendered him totally insensible to the promptings of love and affection when his interest seemed to require that they should be disregarded. His ruthless abandonment of Josephine is a proof of this. And the insensibility with which he appears to have regarded the sacrifice of myriads of Frenchmen to his lust for power, leads us to form a very low estimate of the kindness or goodness of his heart. Two facts of his life stand prominently forward as evidence-the one of the dark and arbitrary injustice of his nature, the other of a contemptible jealousy and littleness. These are the judicial murder of the Duke d'Enghien, and the vindictive and unchivalrous persecution of the talented Madame de Staël, and the amiable Louisa, queen of Prussia. JOE MILLER It would be curious to note in how many cases the principle of lucus a non lucendo has been used, sometimes unintentionally, and sometimes perhaps as a joke, in the application of names. The man whose name is now the representative of the very idea of joking, Joe Miller, is said never to have uttered a joke. This reputed hero of all jokes, in reality an eminent comic actor of the earlier part of the last century, was born in the year 1684; he was no doubt of obscure origin, but even the place of his birth appears to be unknown. In the year 1715, his name occurs for the first time on the bills of Drury Lane theatre as per-forming, on the last day of April, the part of Young Clincher in Farquhar's comedy of The Constant Couple; or a Trip to the Jubilee. Whatever may have been his previous career, it appears certain that his debut was a successful one, for from this time he became regularly engaged on the boards of Drury. It was the custom at that time, during the season when the regular theatres were closed, for the actors to perform in temporary theatres, or in booths erected at the several fairs in and near the metropolis, as in Bartholomew's Fair, Smithfield May Fair, Greenwich Fair, and, in this particular year, at the Frost Fair on the frozen Thames, for it was an extraordinary severe season. We find Joe Miller performing with one of the most celebrated of these movable companies-that of the well-known Pinkethman. At Drury Lane, Miller rose constantly in public esteem. At his benefit on the 25th of April 1717, when he played the part of Sir Joseph Whittol, in Congreve's Old Bachelor, the tickets were adorned with a design from the pencil of Hogarth, which represented the scene in which Whittol's bully, Noll, is kicked by Sharper. The original engraving is now extremely rare, and therefore, of course, very valuable. For a rather long period we find Joe Miller acting as a member of the Drury Lane company, and, in the vacation intervals, first associated with Pinkethman, and subsequently established as an independent booth-theatre manager himself. Joe appears also to have been a favourite among the members of his profession, and it has been handed down to us, through tradition and anecdote, that he was a regular attendant at the tavern, still known as the 'Black Jack,' in Portsmouth Street, Clare Market, then the favourite resort of the performers at Drury Lane and Lincoln's Inn Fields' theatres, and of the wits who came to enjoy their society. It is said that at these meetings Miller was remarkable for the gravity of his demeanour, and that he was so completely innocent of anything like joking, that his companions, as a jest, ascribed every new jest that was made to him.  Joe Miller's last benefit-night was the 13th of April 1738. He died on the 15th of August of the same year; and the paragraphs which announce his death in the contemporary Press shew that he was not only greatly admired as an actor, but that he was much esteemed for his personal character. Miller was interred in the burial-ground of the parish of St. Clement Danes, in Portugal Street, where a tombstone was erected to his memory. About ten years ago, that burial-ground, by the removal of the mortuary remains, and the demolition of the monuments, was converted into a site for King's College Hospital. Whilst this not unnecessary, yet undesirable, desecration was in progress, the writer saw Joe's tombstone lying on the ground; and, being told that it would be broken up and used as materials for the new building, he took an exact copy of the inscription, which was as follows: Here lye the Remains of Honest Jo: MILLER, who was a tender Husband, a sincere Friend, a facetious Companion, and an excellent Comedian. He departed this Life the 15th day of August 1738, aged 54 years. If humour, wit, and honesty could save The humorous, witty, honest, front the grave, The grave had not so soon this tenant found, Whom honesty, and wit, and humour, crowned; Could but esteem, and love preserve our breath, And guard us longer from the stroke of Death, The stroke of Death on him had later fell, Whom all mankind esteemed and loved so well. From respect to social worth, mirthful qualities, and histrionic excellence, commemorated by poetic talent in humble life, the above inscription, which Time had nearly obliterated, has been preserved and transferred to this Stone, by order of MR. JARVIS BUCK, Churchwarden, A.D. 1816.' The 'merry memory' of the comedian, the phrase used in one of the newspaper-paragraphs annoumcing Joe Miller's death, and the wit and humour ascribed to him in the epitaph, perhaps relate especially to his acting, or they would seem to contradict the tradition of his incapacity for making a joke. It was after his death, however, that he gained his fame as a jester. Among the society in which he usually mixed was a dramatic writer of no great merit, named John Mottley, the son of a Jacobite officer. This man was reduced to the position of living on the town by his wits, and in doing this he depended in a great measure on his pen. Among the popular publications of that time, was a kind easy of compilation, consisting substantially of the same jests, ever newly vamped up, with a few additions and variations. It was a common trick to place on the title of one of these brochures the name of some person of recent celebrity, in order to give it an appearance of novelty. Thus, there had appeared in the sixteenth century, Scogan's Jests and Skelton's Jests; in the seventeenth, Tarlton's Jests, Hobson's Jests, Peele's Jests, Hugh Peter's Jests, and a multitude of others; and in the century following, previous to the death of Joe Miller in 1738, Pinkethman's Jests, Polly Peachum's Jests, and Ben Jonson's Jests. It speaks strongly for the celebrity of Joe Miller, that he had hardly lain a year in his grave, when his name was thought sufficiently popular to grace the title of a jest-book; and it was Mottley who, no doubt pressed by necessity, undertook to compile a new collection which was to appear under it. The title of this volume, which was published in 1739, and sold for one shilling, was Joe Miller's Jests: or, the Wit's Vademecuns. It was stated in the title to have been 'first carefully collected in the company, and many of them transcribed from the mouth, of the facetious gentleman whose name they bear; and now set forth and published by his lamentable friend and former companion, Elijah Jenkins, Esq.' This was of course a fictitious name, under which Mottley chose to conceal his own. It must not be concealed that there is considerable originality in Mottley's collection-that it is not a mere republication, under a different name, of what had been published a score of times before; in fact, it is evidently a selection from the jokes which were then current about the town, and some of them apparently new ones. This was perhaps the reason of its sudden and great popularity. A second and third edition appeared in the same year, and it was not only frequently reprinted during the same century, but a number of spurious books appeared under the same title, as well as similar collections, under such titles as The New Joe Miller, and the like. It appears to have been the custom, during at least two centuries, for people who were going to social parties, to prepare themselves by committing to memory a selection of jokes from some popular jest-book; the result of which would of course be, that the ears of the guests were subjected to the old jokes over and over again. People whose ears were thus wearied, would often express their annoyance, by reminding the repeater of the joke of the book he had taken it from; and, when the popularity of Joe Miller's jests had eclipsed that of all its rivals, the repetition of every old joke would draw forth from some one the exclamation: 'That's a Joe Miller!' until the title was given indiscriminately to every jest which was recognised as not being a new one. Hence arose the modern fame of the old comedian, and the adoption of his name in our language as synonymous with 'an old joke.' The S. Duck, whose name figures as author of the verses on Miller's tombstone, and who is alluded to on the same tablet, by Mr. Churchwarden Back, as an instance of 'poetic talent in humble life,' deserves a short notice. He was a thresher in the service of a farmer near Kew, in Surrey. Imbued with an eager desire for learning, he, under most adverse circumstances, managed to obtain a few books, and educate himself to a limited degree. Becoming known as a rustic rhymer, he attracted the attention of Caroline, queen of George II, who, with her accustomed liberality, settled on him a pension of £30 per annum; she made him a yeoman of the Guard, and installed him as keeper of a kind of museum she had in Richmond Park, called Merlin's Cave. Not content with these promotions, the generous, but perhaps inconsiderate queen, caused Duck to be admitted to holy orders, and preferred to the living of Byfleet, in Surrey, where he became a popular preacher among the lower classes, chiefly through the novelty of being the 'Thresher Parson' This gave Swift occasion to write the following quibbling epigram: The thresher Duck could o'er the queen prevail; The proverb says-' No fence against a flail.' From threshing corn, he turns to thresh his brains, For which her majesty allows him grains; Though 'tis confest, that those who ever saw His poems, think 'em all not worth a straw. Thrice happy Duck! employed in threshing stubble! Thy toil is lessened, and thy profits double. One would suppose the poor thresher to have been beneath Swift's notice, but the provocation was great, and the chastisement, such as it was, merited. For, though few men had ever less pre-tensions to poetical genius than Duck, yet the court-party actually set him up as a rival, nay, as superior, to Pope. And the saddest part of the affair was, that Duck, in his utter simplicity and ignorance of what really constituted poetry, was led to fancy himself the greatest poet of the age. Consequently, considering that his genius was neglected, that he was not rewarded according to his poetical deserts, by being made the clergy-man of an obscure village, he fell into a state of melancholy, which ended in suicide; affording another to the numerous instances of the very great difficulty of doing good. If the well-meaning queen had elevated Duck to the position of farm-bailiff, he might have led a long and happy life, amongst the scenes and the classes of society in which his youth had passed, and thus been spared the pangs of disappointed vanity and misdirected ambition. THE BATTLE OF OTTERBOURNE AND CHEVY CHASEThe famous old ballad of Chevy Chase is subject to twofold confusion. There are two, if not three, wholly different versions of the ballad; and two wholly independent incidents mixed up by an anachronism. The battle of Otterbourne was a real event. In 1388, the border chieftains carried on a ruthless warfare. The Scots ravaged the country about Carlisle, and carried off many hundred prisoners. They then crossed into Northumberland, and committed further ravages. On their return home, they attacked a castle at Otter-bourne, close to the Scottish border; but they were here overtaken, on the 15th of August, by an English force under Henry Percy, surnamed Hotspur, son of the Earl of Northumberland. James, Earl of Douglas, rallied the Scots; and there ensued a desperately fierce battle. The earl was killed on the spot; Lord Murray was mortally wounded; while Hotspur and his brother, Ralph Percy, were taken prisoners. It appears, moreover, that nearly fifty years after this battle, a private conflict took place between Hotspur's son and William, Earl of Douglas. There was a tacit understanding among the border families, that none should hunt in the domains of the others without permission; but the martial families of Percy and Douglas being perpetually at fend, were only too ready to break through this rule. Percy crossed the Cheviots on one occasion to hunt without the leave of Douglas, who was either lord of the soil or warden of the marches; Douglas resisted him, and a fierce conflict ensued, the particulars of which were not historically recorded. Now, it appears that some ballad-writers of later date mixed up these two events in such a way as to produce a rugged, exciting story out of them. The earliest title of the ballad was, The Hunting á the Cheviat; this underwent changes until it came simply to Chevy Chase. In the Rev. George Gilfillan's edition of Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, the oldest known version of the ballad is copied from Hearne, who printed it in 1719 from an old manuscript, to which the name of Rychard Sheale was attached. Hearne believed this to be one Richard Sheale, who was living in 1588; but Percy, judging from the language and idiom, and from an allusion to the ballad in an old Scottish prose work, printed about 1548, inferred that the poet was of earlier date. Various circumstances led Percy to believe that the ballad was written in the time of Henry VI. As given by Hearne and Percy, the Hunting á the Cheviat occupies forty-five stanzas, mostly of four lines each, but some of six, and is divided into two 'Fits' or Sections. The ruggedness of the style is sufficiently shewn in the first stanza: The Persè owt of Northombarlande, And a vowe to God mayde he, That he wolde hunte in the mountayns Off Chyviat within dayes thre, In the manger of doughè. Dogles, And all that ever with him be. The ballad relates almost wholly to the conflict arising out of this hunting, and only includes a few incidents which are known to have occurred at the battle of Otterbourne-such as the death of Douglas and the captivity of Hotspur. One of the stanzas runs thus: Worde ys commyn to Eaden-burrowe, To Jamy the Skottishe kyng, That dougheti Duglas, leyff-tennante of the Merchis, He lay slayne Cheviat within. Percy printed another version from an old manuscript in the Cotton Library. There is also another manuscript of this same version, but with fewer stanzas, among the Harleian Collection. This ballad is not confined to the incidents arising out of the hunting by Percy, but relates to the raids and counter-raids of the border-chieftains. Indeed, it accords much better with the historical battle of Otterbourne than with the private feud between the Douglas and the Percy. It consists of seventy stanzas, of four lines each; one stanza will suffice to shew the metre and general style: Thus Syr nary Percye toke the fylde, For soth, as I you saye: Jest' Cryste in hevyn on hyght Dyd helpe hym well that daye. But the Chevy Chase which has gained so much renown among old ballads, is neither of the above. Addison's critique in the Spectator (Nos. 70 and 74) related to a third ballad, which Percy supposes cannot be older than the reign of Elizabeth, and which was probably written after-perhaps in consequence of-the eulogium passed by Sir Philip Sidney on the older ballad. Sidney's words were: I never heard the old song of Percy and Douglas, that I found not my heart more moved than with a trumpet; and yet it is sung by some blind crowder with no rougher voice than rude style, which being so evil-apparel'd in the dust and cobweb of that uncivil age, what would it work trimmed in the gorgeous eloquence of Pindar! Addison, approving of the praise here given, dissents from the censure. 'I must, however,' he says, 'beg leave to dissent from so great an authority as that of Sir Philip Sidney, in the judgment which he has passed as to the rude style and evil apparel of this antiquated song; for there are several parts in it where not only the thought but the language is majestic, and the numbers sonorous; at least the apparel is much more gorgeous than many of the poets made use of in Queen Elizabeth's time.' This is taken as a proof that Addison was not speaking of the older versions. Nothing certain is known of the name of the third balladist, nor of the time when he lived; but there is internal evidence that he took one orboth of the older versions, and threw them into a more modern garb. His Chevy Chase consists of seventy-two stanzas, of four lines each, beginning with the well-known words: God prosper long our noble king, Our lives and safetyes all; A woful hunting once there did In Chevy Chase befall. The ballad relates mainly to the hunting exploit, and what followed it: not to the battle of Otterbourne, or to the border-raids generally. Addison does not seem to refer in his criticism to the original ballad; he praises the third ballad for its excellences, without comparing it with any other. Those who have made that comparison, generally admit that the later balladist improved the versification, the sentiment, and the diction in most cases; but Bishop Percy contends that in some few passages the older version has more dignity of expression than the later. He adduces the exploit of the gallant Witherington: For Wetharryngton my harte was wo, That ever he slayne shulde be; For when both hys leggis were hewyne in to, Yet he knyled and fought on hys kne. The bishop contends that, if this spelling be a little modernised, the stanza becomes much more dignified than the corresponding stanza in the later version For Witherington needs must I wayle, As one in doleful dumpes; For when his leggs were smitten off, He fought upon his stumpes. In any sense, however, both the versions-or rather all three versions-take rank among our finest specimens of heroic ballad-poetry. It will be learned, not without interest, that certain relics or memorials of the fight of Otterbourne are still preserved in Scotland. The story of the battle represents Douglas as having, in a personal encounter with Percy in front of Newcastle, taken from him his spear and its pennon or hanging flag, saying he would carry it home with him, and plant it on his castle of Dalkeith. The battle itself was an effort of Percy to recover this valued piece of spoil, which, however, found its way to Scotland, notwithstanding the death of its captor. One of the two natural sons of Douglas founded the family of Douglas of Cavers, in Roxburghshire, which still exists in credit and renown; and in their hands are the relics of Otterbourne, now nearly five hundred years old. It is found, however, that history has somewhat misrepresented the matter.  The Otterbourne flag proves to be, not a spear-pennon, but a standard thirteen feet long, bearing the Douglas arms: it evidently has been Douglas's own banner, which of course his son would be most anxious to preserve and carry home. The other relic consists of a pair of, apparently, lady's gauntlets, bearing the white lion of the Percies in pearls, and fringed with filigree-work in silver. It now seems most probable that this had been a love-pledge carried by Percy, hanging from his helmet or his spear, as was the fashion of those chivalrous times, and that it was the loss of this cherished memorial which caused the Northumbrian knight to pursue and fight the Earl of Douglas. We owe the clearing up of this matter to a paper lately read by Mr. J. A. H. Murray, of Hawick, to the Hawick Archaeological Society, when the Douglas banner and the Percy gauntlets were exhibited. It may be said to indicate a peculiar and surely very interesting element in British society, that a family should exist which has preserved such relics as these for half a thousand years. Let American readers remark, in particular, the banner was laid up in store at Cavers more than a hundred years before America was discovered. The writer recalls with curious feelings having been, a few years ago, at a party in Edinburgh where were present the Duke of Northumberland, representative of the Percy of Otterbourne celebrity, and the younger Laird of Cavers, representative of the Douglas whose name, even when dead, won that hard-fought field. FIRST BRITISH STEAM PASSAGE-BOATOn the 15th of August 1812, there appeared in the Greenock Advertiser, an announcement signed Henry Bell, and dated from the Helensburgh Baths, making the public aware that thereafter a steam passage-boat, the COMET, would ply on the Clyde, between Glasgow and Greenock, leaving the former city on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and the latter on the other lawful days of the week; the terms 4s. for the best cabin, and 3s. for the second. This vessel, one of only twenty-five tons burden, had been prepared in the building yard of John and Charles Wood, Port-Glasgow, during the previous winter, at the instance of the above-mentioned Henry Bell, who was a simple uneducated man, of an inventive and speculative turn of mind, who amused himself with projects, while his more practical wife kept a hotel and suite of baths at a Clyde watering-place.  The application of steam to navigation had been experimentally proved twenty-four years before, by Mr. Patrick Miller, a Dumfriesshire gentleman, under the suggestions of Mr. James Taylor, and with the engineering assistance of Mr. Alexander Symington: more recently, a steamer had been put into regular use by Mr. Robert Fulton, on the Hudson river in America. But this little Comet of Henry Bell, of the Helensburgh Baths, was the first example of a steam-boat brought into serviceable use within European waters. In its proposed trips of five-and-twenty miles, it is understood to have been successful as a commercial speculation; insomuch that, presently after, other and larger vessels of the same kind were built and set agoing on the Clyde. It is an interesting circumstance, that steam-navigation thus sprung up in a practical form, almost on the spot where James Watt, the illustrious improver of the steam-engine, was born. This eminent man appears never to have taken any active concern in the origination of steam-navigation; but, so early as 1816, when he, in old age, paid a visit to his native town of Greenock, he went in one of the new vessels to Rothesay and back, an excursion which then occupied the greater portion of a whole day. Mr. Williamson, in his Memorials of James Watt, relates an anecdote of this trip. 'Mr. Watt entered into conversation with the engineer of the boat, pointing out to him the method of backing the engine. With a foot-rule he demonstrated to him what was meant. Not succeeding, however, he at last, under the impulse of the ruling passion, threw off his over-coat, and putting his hand to the engine himself, shewed the practical application of his lecture. Previously to this, the back-stroke of the steam-boat engine was either unknown, or not generally acted on. The practice was to stop the engine entirely, a considerable time before the vessel reached the point of mooring, in order to allow for the gradual and natural diminution of her speed.' It is a great pity that Henry Bell's Comet was not preserved, which it would have been en-titled to be, as a curiosity. It was wrecked one day, by running ashore on the Highland coast, when Bell himself was on board-no lives, however, being lost. The annexed representation of the proto-steamer of Europe, was obtained by Mr. Williamson, from an original drawing which had been in the possession of Henry Bell, and was marked with his signature. BALLAD-SINGERS AND GRUB-STREET POETSIt was in reality Montaigne, who made the shrewd but now somewhat musty remark: 'Let me have the making of a nation's ballads, and I care little who makes its laws.' The old French-man had observed the powerful effect of caustic satire wedded to popular tunes. It has been told, with truth, how Lilliburlero gave the finishing-stroke to the Great Revolution of 1688, and 'sung King James II out of his three kingdoms;' and it is equally historic, that Béranger was a power in the state, seriously damaging to the stability of the restored Bourbon dynasty. Shakspeare has happily delineated the popular love of ballads, in the sheep-shearer's feast-scene of The Winter's Tale. The rustics love 'a ballad in print,' for then they 'are sure they are true;' and listen with easy credulity to those which tell of 'strange fish,' and stranger monstrosities. It must not be imagined that Autolycus's pack contains caricatured resemblances of popular ballads; for the Roxburghe, Pepysian, and other collections, preserve specimens of lyrics, seriously published and sold, which are quite as absurd as anything mentioned by Shakspeare. In the British Musemn is one entitled Prides Fall: or a Warning for all English Women, by the example of a Strange Monster, lately born 'in Germany, by a Merchant's proud Wife at Geneva; which is adorned with a grim wood-cut of the monster, and is intended to frighten women from extravagant fashions in dress. From the head to the foot Monster-like was it born, Every part had the shape Of Fashions daily worn. The moral of the story is, that all women should 'take heed of wanton pride,' and remember that this sin is rapidly bringing forth a day of judgment, and the end of the world. Such moralities were like the ballad of Autolycus, 'written to a very doleful tune,' and chanted by a blind fiddler to an equally doleful fiddle. Shakspeare has expressed his con-tempt for the literary merits of these effusions, when he makes Benedick speak of picking out his eyes ' with a ballad-maker's pen;' but the pages of Percy, Ritson, and Evans are sufficient to establish the claim of many balladists to attention and respect, for the simple imagery and natural beauty of their effusions. Gifford says, 'in Jonson's time, scarcely any ballad was printed without a wood-cut illustrative of its subject. If it was a ballad of 'pure love,' or of 'good life,' which afforded no scope for the graphic talents of the Grub-Street Apelles, the portrait of 'good Queen Elizabeth,' magnificently adorned with the globe and sceptre, formed no unwelcome substitute for her loyal subjects.' Ballad-buyers were fond of seeing these familiar wood-cuts, they were ' old favourites,' and so well-worn by printers, that it is not unusual to find cuts, evidently executed in the days of James I, worked by ballad-printers during the reign of Anne; so indestructible were the coarse old wood-engravings which were then used 'to adorn' the 'doleful tragedies,' or 'merry new ballads' of the Grub-Street school of sentiment.  The constables kept a wary eye on the political or immoral ballad-singer of London; but Chettle, in Kind Heart's Dream, 1592, notes 'that idle, upstart generation of ballad-singers,' who ramble in the outskirts, and are 'able to spread more pamphlets, by the state forbidden, than all the book-sellers in London; for only in this city is straight search; abroad, small suspicion; especially of such petty pedlars.' A dozen groats' worth of ballads is said to be their stock in trade; but they all dealt in the pamphlets of a few leaves, that were industriously concocted on all popular subjects by the hack-writers of the day. In the curious view of the interior of the Royal Exchange, executed by Hollar in 1644, and depicting its aspect when crowded by merchants and visitors, we see one of these itinerant ballad and pamphlet mongers plying her trade among the busy group. This figure we copy above, on a larger scale than the original, which gives, with minute truthfulness, the popular form of the ballads of that day, printed on a broad sheet, in double columns, with a wood-cut at the head of the story. The great Civil War was a prolific source of ballad-writing and pamphleteering. It would not be easy to carry libel to greater length than it was then carried, and especially by ballad-singers. These 'waifs and strays,' many of them being the productions of men of some literary eminence, have been gathered into volumes, affording most vivid reminiscences of the strong party-hatred of the time. The earliest of these collections was published in 1660, and is entitled Ratts Rhimed to Death: or, the Rump parliament hang'd up in the Shambles-the title sufficiently indicating the violent character of the songs, gathered under this strange heading. 'They were formerly printed on loose sheets,' says tho collector to the reader; adding, 'I hope you will pardon the ill tunes to which they are to be sung, there being none bad enough for them.' Most of them are too coarse for modern quotation; the spirit of all maybe gathered from the opening stanza of one: Since sixteen hundred forty and odd, We have soundl been lash'd with our own rod, And have bow'd oyurselves down at a tyrant's nod- Which nobody can deny. he violent personality of others may be under-stood in reading a few stanzas of A Hymn to the Gentle Craft, or Hewson's Lamentation. Colonel Hewson was one of Cromwell's most active officers, and said to have originally been a shoemaker; he had by accident lost an eye. Listen awhile to what I shall say, Of a blind cobbler that's gone astray, Out of the parliament's highway. Good people, pity the blind! His name you wot well is Sir John Hewson, Whom I intend to set my muse on, As great a warrior as Sir Miles Lewson. Good people, pity the blind! He 'd now give all the shoes in his shop, The parliament's fury for to stop, Whip cobbler, like any town-top. Good people, pity the blind! Oliver made him a famous lord, That he forgot his cutting-hoard; But now his thread 's twisted to a cord. Good people, pity the blind! Sing hi, ho, Hewson!-the state ne'er went upright, Since cobblers could pray, preach, govern, and fight; We shall see what they'll do now you're out of sight. Good people, pity the blind! For some time after the Restoration, the popular songs were all on the court-side, and it was not until Charles II's most flagrant violations of political liberty and public decency, that they took an opposite turn. The court then guarded itself by imposing a licence upon all ballad-singers and pamphleteers. One John Clarke, a bookseller, held this right to license of Charles Killigrew, the Master of the Revels, and advertised in the London Gazette of 1682 as follows: These are to give notice to all ballad-singers, that they take out licences for singing and selling of ballads and small books, according to an ancient custom. And all persons concerned are hereby desired to take notice of, and to suppress, all moumtebanks, rope-dancers, prize-players, and such as make shew of motions and strange sights, that have not a licence in red and black letter, under the hand and seal of the said Charles Killigrew, Master of Revels to his Majesty. In 1684, a similar advertisement orders all such persons 'to come to the office to change their licences as they are now altered.' The court had reason for all this, for the ballad-singers had become as wide-mouthed as in the days of Cromwell; while the court-life gave scope to obscene allusion that exceeded anything before attempted. The short reign of James II, the birth of the Prince of Wales, and advent of the Prince of Orange, gave new scope for personal satire. Of all the popular songs ever written, none had greater effect than Lilliburlero (attributed to Lord Wharton), which Burnet tells us 'made an impression on the king's army that cannot be imagined by those that saw it not. The whole army, and at last the people, both in city and country, were singing it perpetually. And perhaps never had so slight a thing so great an effect.' Some of these songs were written to popular old tunes; that of Old Simon the King accompanied the Sale of Old State Household Stuff, when James II. was reported to have had an intention to remove the hangings in the Houses of Parliament, and wainscot the rooms; one stanza of this ditty we give as a sample of the whole: Come, buy the old tapestry-hangings Which hung in the House of Lords, That kept the Spanish invasion And powder plot on records: A musty old Magna Charta That wants new scouring and cleaning, Writ so long since and so dark too, That 'tis hard to pick out the meaning. Quoth Jemmy, the bigoted king, Quoth Jemmy, the politick thing; With a threadbare-oath, And a Catholic troth, That never was worth a farthing! The birth of the Prince of Wales was a fertile theme for popular rhymes, written to equally popular tunes. The first verse of one, entitled Father Petre's Policy Discovered; or the Prince of Wales proved to be a Popish Perkin, runs thus: In Rome there is a most fearful rout; And what do you think it is about? Because the birth of the babe 's come out. Sing lullaby baby, by, by, by. The zest with which such songs would be sung in times of great popular excitement can still be imagined, though scarcely to its full extent. Another, on The Orange, contains this strong stanza: When the Army retreats, And the Parliament sits, To vote our King the true use of his wits; 'Twill be a sad means, When all he obtains Is to have his Calves-head dress'd with other men's brains; And an Orange. No enactments could reach these lampoons, nor the fine or imprisonment of a few wretched ballad-singers stop their circulation. Lannon, a Dutch artist, then resident in London, has preserved a representation of one of these women offering 'a merry new ballad,' to her customers; and she has a bundle of others in her apron pocket. To furnish these 'wandering stationers,' as they were termed, with their literary wants, a band of Grub-street authors existed, in a state of poverty and degradation of which we now can have little idea, except by referring to contemporary writers. The half-starved hacks are declared to fix their highest ideas of luxurious plenty in Gallons of beer and pounds of bullock's liver. Pope in the Dunciad, has given a very low picture of the class: Not with less glory mighty Dulness crown'd, Shall take through Grub Street her triumphant round: And, her Parnassus glancing o'er at once, Behold a hundred sons, and each a dunce. In Fielding's Author's Farce, 1730, we are introduced to a bookseller's workroom, where his hacks are busy concocting books for his shop. One of them complains that he 'has not dined these two days,' and the rest find fault with the disagree-able character of their employment; when the bookseller enters, and the following conversation ensues: Book: Fie upon it, gentlemen!-what, not at your pens? Do you consider, Mr. Quibble, that it is above a fortnight since your Letter from a Friend in the Country was published? Is it not high time for an answer to come out? At this rate, before your answer is printed, your letter will be forgot: I love to keep a controversy up warm. I have had authors who have writ a pamphlet in the morning, answered it in the afternoon, and compromised the matter at night. Quibble: Sir, I will be as expeditious as possible. Book. Well, Mr. Dash, have you done that murder yet? Dash: Yes, sir; the murder is done. I am only about a few moral reflections to place before it. Book. Very well; then let me have a ghost finished by this day seven-night. Dash: What sort of a ghost would you have, sir? The last was a pale one. Book: Then let this be a bloody one.  This last hit seems levelled at Defoe, who in reality concocted a very seriously-told ghost-story, The Apparition of Mrs. Veal, to enable a book-seller to get rid of an unsaleable book, Drelincourt on Death, which was directly puffed by the ghost assuring her friend, Mrs. Bargrave, that it was the best work on the subject. Pope and his friends amused and revenged themselves on Curll the bookseller, who was the chief publisher of trashy literature in their day, by an imaginary account of his poisoning and preparation for death, as related by 'a faithful, though unpolite historian of Grub Street.' In the course of the narrative, instructions are given how to find Mr. Curll's authors, which indicates the poverty-stricken character of the tribe: At a tallow-chandler's in Petty France, half-way under the blind arch, ask for the historian; at the Bedstead and Bolster, a music-house in Moorfields, two translators in a bed together; at a blacksmith's shop in the Friars, a Pindaric writer in red stockings; at Mr. Summers's, a thief-catcher's in Lewkner's Lane, the man that wrote against the impioty of Mr. Rowe's plays; at the farthing pie-house, in Tooting Fields, the young man who is writ-mg my new pastorals; at the laundress's, at the Hole-in-thewall, in Cursitor's Alley, up three pair of stairs, the author of my church history; you may also speak to the gentleman who lies by him in the flock-bed, my index-maker. Grub Street no longer appears by name in any London Directory; yet it still exists and preserves some of its antique features, though it has for the last forty years been called Milton Street. It is situated in the parish of St. Giles's, Cripplegate, leading from Fore Street northerly to Chiswell Street. Its contiguity to the artillery-ground in Bunhill Fields, where the city trainband exercised, is amusingly alluded to in The Tatler, No. 41, where their redoubtable doings are narrated: Happy was it that the greatest part of the achievements of this day was to be performed near Grub Street, that there might not be wanting a sufficient number of faithful historians, who being eye-witnesses of these wonders, should impartially transmit them to posterity. The concocters of News-letters were among the most prolific and unblushing authors of 'Grub-street literature.' Steele, in the periodical just quoted, alludes to some of them by name: Where Prince Eugene has slain his thousands, Boyer has slain his ten thousands; this gentleman can, indeed, be never enough commended for his courage and intrepidity during this whole war.' 'Mr. Buckley has shed as much blood as the former.' 'Mr Dyer was particularly famous for dealing in whales, insomuch that in five months' time he brought three into the mouth of the Thames, besides two porpuses and a sturgeon. The judicious and wary Mr. Dawks bath all along been the rival of this great writer, and got himself a reputation from plagues and famines, by which he destroyed as great multitudes, as he has lately done by the sword. In every dearth of news, Grand Cairo was sure to be unpeopled. This mob of unscrupulous scribblers, and the ballad-singers who gave voice to their political pasquinades, occasioned the government much annoyance at times. The pillory and the jail were tried in vain. Heedless on high stood unabashed Defoe. It was the ambition of speculative booksellers to get a government prosecution, for it insured the sale of large editions. Vamp, the bookseller in Samuel Foote's play, called the Author, 1757, makes that worthy shew the side of his head and his ears, cropped in the pillory for his publications; yet he has a certain business pride, and declares, 'in the year forty-five, when I was in the treasonable way, I never squeaked; I never gave up but one author in my life, and he was dying of a consumption, so it never came to a trial.' The poor ballad-singers, less fortunate, could be seized at once, and summarily punished by any magistrate. The newspapers of the day often allude to these persecutors. The Middlesex grand jury, in 1716, denounced ' the singing of scandalous ballads about the streets as a common nuisance; tending to alienate the minds of the people.' The Weekly Packet, which gives this information, adds, 'we hear an order will be published to apprehend those who cry about, or sing, such scandalous papers.' Read's Weekly Journal tells us, in July 1731, that 'three hawkers were committed to Tothill Fields Bridewell, for crying about the streets a printed paper called Robin's Game, or Seven's the Main;' a satire on the ministry of Sir Robert Walpole. In July 1763, we are told 'yesterday evening two women were sent to Bridewell, by Lord Bute's order, for singing political ballads before his lordship's door in South Audley Street.' State prosecutions have never succeeded in repressing political satire; it has died a natural death for want of strong food! THE MINSTRELS FESTIVAL AT TUTBURYThe castle of Tutbury was a place of great strength, built shortly after the Conquest by Henry de Ferrars, one of William's Norman noblemen, who had received the gift of large possessions in Derbyshire, Staffordshire, and the neighbouring counties. It stands upon a hill so steep on one side that it there needs no defence, whilst the other three were strongly walled by the first owner, who lost his property by joining in the rebellion of Simon de Montfort against Henry III. It was afterwards in the possession of the Dukes of Lancaster, one of whom, the celebrated John of Gaunt, added to its fortifications. During the civil war, it was taken and destroyed by the parliamentary forces; and the ruins only now remain. During the time of the Dukes of Lancaster, the little town of Tutbury was so enlivened by the noble hospitality they kept up, and the great concourse of people who gathered there, that some regulations became necessary for keeping them in order; more especially those disorderly favourites of both the high and low, the wandering jongleurs or minstrels, who displayed their talents at all festive-boards, weddings, and tournaments. A court was therefore appointed by John of Gaunt, to be held every year on the day after the festival of the Assumption of the Virgin, being the 16th of August, to elect a king of the minstrels, try those who had been guilty of misdemeanors during the year, and grant licences for the future year, all which were accompanied by many curious observances. The wood-master and rangers of Needwood Forest began the festivities by meeting at Berkley Lodge, in the forest, to arrange for the dinner which was given them at this time at Tutbury Castle, and where the buck they were allowed for it should be killed, as also another which was their yearly present to the prior of Tutbury for his dinner. These animals having received their death-blow, the master, keepers, and deputies met on the Day of Assumption, and rode in gay procession, two and two, into the town, to the High Cross, each carrying a green bough in his hand, and one bearing the buck's head, cut off behind the ears, garnished with a rye of pease and a piece of fat fastened to each of the antlers. The minstrels went on foot, two and two, before them, and when they reached the cross, the keeper blew on his horn the various hunting signals, which were answered by the others; all passed on to the churchyard, where, alighting from their horses, they went into the church, the minstrels playing on their instruments during the time of the offering of the buck's head, and whilst each keeper paid one penny as an offering to the church. Mass was then celebrated, and all adjourned to the good dinner which was prepared for them in the castle; towards the expenses of which the prior gave them thirty shillings. On the following day, the minstrels met at the bailiff's house, in Tutbury, where the steward of the court, and the bailiff of the manor, who were noblemen of high rank, such as the Dukes of Lancaster, Ormond, or Devonshire, with the wood-master, met them. A procession was formed to go to church, two trumpeters walking first, and then the musicians on stringed instruments, all playing; their king, whose office ended on that day, had the privilege of walking between the steward and bailiff, thus, for once at least, taking rank with nobility; after them came the four stewards of music, each carrying a white wand, followed by the rest of the company. The psalms and lessons were chosen in accordance with the occasion, and each minstrel paid a penny, as a due to the vicar of Tutbury.  On their return to the castle-hall, the business of the day began by one of the minstrels performing the part of a herald, and crying: 'Oyez, oyez, oyez! all minstrels within this honour, residing in the counties of Stafford, Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, and Warwick, come in and do your suit and service, or you will be amerced.' All were then sworn to keep the King of Music's counsel, their fellows', and their own. A lengthy charge from the steward followed, in which he expatiated on the antiquity and excellence of their noble science, passing from Orpheus to Apollo, Jubal, David, and Timotheus, instancing the effect it had upon beasts by the story of a gentleman once travelling near Royston, who met a herd of stags upon the road following a bagpipe and violin: when the music played, they went forward; when it ceased, they all stood still; and in this way they were conducted out of Yorkshire to the king's palace at Hampton Court. The jurors then proceeded to choose a new king, who was taken alternately from the minstrels of Staffordshire and Derbyshire, as well as four stewards, and retired to consider the offences which were alleged against any minstrel, and fine him, if necessary. During this time, the old stewards brought into the court a treat of wine, ale, and cakes, and the minstrels diverted themselves and the company by playing their merriest airs. The new king entered, and was presented by the jurors, the old one rising from his place, and giving the white wand to his successor, pledging him in a cup of wine, and bidding hint joy of the honour he had received; the old stewards followed his example, and at noon all entered into a fair room within the castle, where the old king had prepared for them a plentiful dinner. The conclusion of the day was much in accordance with the barbarous taste of the times: a bull being given them by the prior of Tutbury, they all adjourned to the abbey gate, where the poor beast had the tips of his horns sawed off, his ears and tail cut off, the body smeared over with soap, and his nose filled with pepper. The minstrels rushed after the maddened creature, and if any of them could succeed in cutting off a piece of his skin before he crossed the river Dove into Derbyshire, he became the property of the King of Music, but if not, he was returned sound and uncut to the prior again. After becoming the king's own, he was brought to the High Street, and there baited with dogs three times; the bailiff then gave the king five nobles, equal to about £1, 13s. 4d., for his right, and sent the bull to the Earl of Devon's manor of Hardwick, to be fed and given to the poor at Christmas. It has been supposed that John of Gaunt, who assumed the title of King of Castile and Leon in right of his wife, introduced this sport in imitation of the Spanish bullfights; but in the end the young men of the neighbourhood, who flocked in great numbers to the festival, could not help interfering with the minstrels, and, taking cudgels of about a yard in length, the one party endeavoured to drive the bull into Derbyshire, the other to keep him in Staffordshire, and this led to such outrage, that many returned home with broken heads. Gradually, as 'old times were changed, old manners gone,' the minstrels fell into disrepute; the castles were destroyed in the civil wars, the nobility spent their time and sought their amusements in London, and harpers were no longer needed to charm away the ennui of their ladies and retainers; the court of minstrels found no employment, and the hull-baiting was strongly objected to by the inhabitants. The Duke of Devonshire consequently abolished the whole proceeding in 1778, after it had lasted through the long period of four hundred years. The manor of Tutbury was one of those held by cornage tenure: in 1569, Walter Achard claimed to be hereditary steward of Leek and Tutbury, in proof of which he shewed a white hunter's horn, decorated with silver gilt ornaments. It was hung to a girdle of fine black silk, adorned with buckles of silver, on which were the arms and the fleurs-de-lis of the Duke of Lancaster, from whom it descended. The Stanhopes of Elvaston were recently in possession of the badge. |