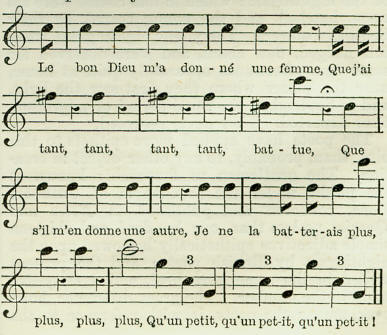

15th AprilBorn: William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, 1721, London; Sir James Clark Ross, navigator, 1800. Died: George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, 1632; Dominico Zampieri (Domenichino), Italian painter, 1641, Naples; Madame de Maintenon, 1719, St. Cyr; William Oldys, antiquary, 1761, London; Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XI, 1764, Paris; Dr. Alexander Murray, philologist, 1813; John Bell, eminent surgeon, 1820, Rome; Thomas Drummond, eminent in physical science, 1840, Dublin. Feast Day: Saints Basilissa and Anastasia, martyrs, 1st century. Saint Paternus, Bishop of Avranches, 563. St. Ruadhan, abbot, 584. St. Munde, abbot, 962. St. Peter Gonzales, 1246. WILLIAM OLDYSQuaint and simpleminded William Oldys gave himself up, heart and soul, to the pleasant task of searching among old literary stores. The period in which he lived and laboured was not one to appreciate the value of such an enthusiast. Booksellers and men of letters found it worth while to make use of him, but it was little in their power to benefit him in return. So he rummaged old book-stalls undisturbed, made his honest notes, collected materials for mighty works contemplated, jotted down gentle indignation at unworthy treatment in endless diaries, and left all these invaluable treasures at his death to be scattered and lost and destroyed. Little is known of his life, and that little, not always of a pleasing nature. 'His parents ' relates Grose-antiquary himself, after another fashion-'dying when he was very young, he soon squandered away his small patrimony, when he became, at first attendant in Lord Oxford's library, and afterwards librarian.' Possibly, the patrimony was very small; possibly, it went in books; be that as it may, it is pleasing to find him in a post so congenial to his tastes. But Lord Oxford died, and Oldys became dependent on the booksellers. How this served his ends, we may judge by an anecdote communicated by the son of a friend of his. It was made known to the Duke of Norfolk one day at dinner, that Oldys had been passing 'many years in quiet obscurity in the Fleet Prison.' The Duke, to his honour, set him free, and got him appointed Norroy King-at-arms. Oldys wrote many valuable articles on various subjects; but his chief remains were manuscript materials laboriously collected for works to come. His discoveries and curiosities,' says D'Israeli, were dispersed on many a fly-leaf, in occasional memorandum-books; in ample marginal notes on his authors. They were sometimes thrown into what he calls his Parchment Budgets, or Bags of Biography - Of Botany- Of Obituary-of Books Relative to London, and other titles and bags, which he was every day filling.' His annotated edition of Longbaine's Dramatic Poets, preserved in the British Museum, is 'not interleaved, but overflowing with notes, written in a very small hand about the margins, and inserted between the lines; nor may the transcriber pass negligently over its corners,' stored with date and reference. He also kept diaries, in which he jotted down work to be done, researches to be made, his feelings, his sorrows, with an infinitude of items, whose loss is to be regretted. In one volume, which has been preserved, he grows melancholy about his work, and sets down a pious misgiving, -'he heapeth up riches, and cannot tell who shall gather them.' In sadder mood still, he includes the contents in a quaint couplet: Fond treasurer of these stores, behold thy fate In Psalm the thirty-ninth, 6, 7, and 8. He sighs over books he has lent, which have not returned. He tells how he wrote some valuable article, of nearly two sheets, and how the book-sellers 'for sordid gain, and to save a little expense in print and paper, got Mr. John Campbell to cross it and cramp it, and play the devil with it, till they squeezed it into less compass than a sheet.' Or again, he growls humorously at old counsellor Fane, of Colchester, who, in formâ, pauperis, deceived me of a good sum of money which he owed Inc, and not long after set up his chariot,' and who ' gave me a parcel of manuscripts, and promised me others, which he never gave me, nor anything else, besides a barrel of oysters.' Probably 'old counsellor Fane' knew his man, not only in the bribe of manuscript, but that of oysters. We know, at least, that when his throat was dry with the dust of folios, Oldys was wont to moisten it. Here is a song 'made extempore by a gentleman, occasioned by a fly drinking out of his cup of ale,' which D'Israeli traces to Oldys: Busy, curious, thirsty fly! Drink with me, and drink as I! Freely welcome to my cup, Couldst thou sip and sip it up; Make the most of life you may: Life is short and wears away. Both alike are mine and thine, Hastening quick to their decline! Thine's a summer, mine no more, Though repeated to threescore! Threescore summers, when they're gone, Will appear as short as one! THE NIGHTINGALE & ITS SONGThe nightingale is pre-eminently the bird of April. Arriving in England about the middle of the month, it at once breaks forth into full song, which gradually decreases in compass and volume, as the more serious labours of life, nest-building, incubating, and rearing the young, have to be performed. The peculiar mode of migration, in reference to the limited range of this bird, has long been a puzzling problem for naturalists. In some districts they are to be heard filling the air with their sweet melody in every hedge-row; while in other places, to all appearance quite as well suited to their habits, not one has ever been observed. And, stranger still, this marked difference, between abundance and total absence of nightingales, exists between places only a few miles apart. It might be supposed that the warmer districts of the kingdom would be most congenial to their habits, yet they are not found in Cornwall, nor in the south of Devonshire, where, in favourable seasons, the orange ripens in the open air. On the other hand, they are seldom heard to the northward of York, while they are plentiful in Denmark. The migration of the nightingale to and in England seems to be conducted in an almost due north and south direction; its eastern limits being bounded by the sea, and its western by the third degree of west longitude, which latter a very few stragglers only ever cross. This line completely cuts off Devonshire and Cornwall, nearly all Wales, and of course Ireland. Its northern limit, on the eastern side, is York; but on the west it has been heard as far north as the neighbourhood of Carlisle. The patriotic Sir John Sinclair, acting on the general rule that migratory song-birds almost always return to their native haunts, endeavoured to establish the nightingale in Scotland, but unfortunately without success. The attempt was conducted on a scale large enough to exhibit very palpable results, in case that the desired end had been practicable. Sir John commissioned a London dealer to purchase as many nightingale's eggs as he could get at the liberal price of one shilling each; these were well packed in wool, and sent down to Scotland by mail. A number of trustworthy men had previously been engaged to find and take especial care of all robin-redbreasts' nests, in places where the eggs could be hatched in perfect safety. As regularly as the parcels of eggs arrived from London, the robins' eggs were removed from their nests and replaced by those of the nightingale; which in due course were sat upon, hatched, and the young reared by their Scottish fosterers. The young nightingales, when full fledged, flew about, and were observed for some time afterwards apparently quite at home, near the places where they first saw the light, and in September, the usual period of migration, they departed. They never returned. The poets have applied more epithets to this bird than, probably, to any other object in creation. The gentleman so favourably known to the public under the pseudonym of Cuthbert Bede, collected and published in Notes and Queries no less than one hundred and thirteen simple adjectives epithetically bestowed upon the nightingale by British poets; and the present writer, in the same periodical, added sixty-five more to the number. The great difference, however, among the poets, is with reference to the character of its song. Milton speaks of it as the: Sweet bird, that shuns the noise of folly, Most musical, most melancholy. To this, Coleridge almost indignantly replies: Most musical, most melancholy bird I' A melancholy bird? 0 idle thought, In nature there is nothing melancholy; But some night wandering man, whose heart was pierced With the remembrance of a grievous wrong, Or slow distemper, or neglected love, And so, poor wretch, filled all things with himself, And made all gentle sounds tell back the tale Of his own sorrows-he, and such as he, First named thy notes a melancholy strain.' Tis the merry nightingale, That crowds, and hurries, and precipitates, With fast thick warble, his delicious notes, As he were fearful that an April night Would be too short for him to utter forth His love chant, and disburden his full soul Of all its music. The classical fable of the unhappy Philomela may have given an ideal tinge of melancholy to the Daulian minstrel's midnight strain; as well as an origin to the once, and even now not altogether forgotten popular error, that the bird sings with its breast impaled upon a thorn. In an exquisite sonnet by Sir Philip Sidney, set to music by Bateson in 1604, we read: The nightingale, as soon as April bringeth Unto her rested sense a perfect waking, While late bare earth, proud of her clothing springeth, Sings out her woes, a thorn her song-book making; And mournfully bewailing, Her throat in tunes expresseth, While grief her heart oppresseth, For Tereus o'er her chaste will prevailing. The earliest notice of this myth by an English poet is, probably, that in the Passionate Pilgrim of Shakspeare. Everything did banish moan, Save the nightingale alone; She, poor bird, as all forlorn, Leaned her breast up till a thorn, And there sung the dolefull'st ditty, That to hear it was great pity. Hartley Coleridge, alluding to the controversy respecting the song of the nightingale, says:-No doubt the sensations of the bird while singing are pleasurable; but the question is, what is the feeling which its song, considered as a succession of sounds produced by an instrument, is calculated to convey to a human listener? When we speak of a pathetic strain of music, we do not mean that either the fiddle or the fiddler is unhappy, but that the tones or intervals of the air are such as the mind associates with tearful sympathies. At the same time, I utterly deny that the voice of Philomel expresses present pain. I could never have imagined that the pretty creature sets its breast against a thorn, and could not have perpetrated the abominable story of Tereus.' And to still further illustrate his opinion, he compares the songs of the nightingale and lark in the following lively poem, extracted from a little known limp volume published at Leeds: Tis sweet to hear the merry lark, That bids a blithe good morrow; But sweeter to hark, in the twinkling dark, To the soothing song of sorrow. Oh, nightingale! what cloth she ail? And is she sad or jolly? For ne'er on earth was sound of mirth So like to melancholy. The merry lark, he soars on high, No worldly thought o'ertakes him; He sings aloud to the clear blue sky, And the daylight that awakes him. As sweet a lay, as loud as gay, The nightingale is trilling; With feeling bliss, no less than his, Her little heart is thrilling. Yet ever and anon a sigh Peers through her lavish mirth; For the lark's bold song is of the sky, And hers is of the earth. By night and day she tunes her lay, To drive away all sorrow; For bliss, alas! to night must pass, And woe may come tomorrow. Tennyson, in his In Memoriam, fully recognizes the characteristics of both joy and grief in the nightingale's song: Wild bird! whose warble liquid, sweet, Rings echo through the budded quicks, Oh, tell me where the senses mix, Oh, tell me where the passions meet, Whence radiate? Fierce extremes employ Thy spirit in the lurking leaf, And in the midmost heart of grief Thy passion clasps a secret joy. Again, he expresses a similar idea in The Gardener's Daughter: Yet might I tell of weepings, of farewells, Of that which came between more sweet than each, In whispers, like the whispers of the leaves, That tremble round a nightingale-in sighs Which perfect joy, perplexed for utterance, Stole from her sister sorrow. Faber, in The Cherwell Water Lily, gives an angelic character to the strains of Philomel: I heard the raptured nightingale Tell from you elmy grove his tale Of jealousy and love, In thronging notes that seem'd to fall, As faultless and as musical As angels' strains above. So sweet, they cast on all things round A spell of melody profound; They charmed the river in its flowing, They stayed the night wind in its blowing, They lulled the lily to her rest, Upon the Cherwell's heaving breast. It seems very probable that Faber had read the following lines by Drummond, of Hawthorn-den: Sweet artless songster, thou my mind doth raise To airs of spheres, yes, and to angels' lays. The beautiful prose passage on the nightingale in Walton's Angler has been frequently quoted, amongst others by Sir Walter Scott, Sir Humphrey Davy, and Bishop Horne; Dr Drake, too, in his Literary Hours, asserts that this description surpasses all that poets have written on the subject. 'The nightingale,' says Walton, 'breathes such sweet, loud music out of her little instrumental throat, that it might make mankind to think miracles are not ceased. He that at mid-night, when the very labourer sleeps securely, should hear, as I have very often, the clear airs, the sweet descants, the natural rising and falling, the doubling and redoubling of her voice, might well be lifted above earth, and say, Lord, what music Hast thou provided for the saints in heaven, when thou affordest bad men such music on earth?' More than two hundred years ago, a learned Jesuit, named Marco Bettini, attempted to reduce the nightingale's song to letters and words; and his attempt has been considered eminently successful. Towards the close of the last century, one Bechstein, a German, neither a scientific naturalist nor a scholar, simply a sportsman and observer of nature, but whose name must ever be connected with singing-birds, improved Bettini's attempt into the following form; which, however uncouth it may look, must be acknowledged by all acquainted with the song a very remarkable imitation, as far as the usual signs of spoken language can represent the different notes and modulations of the voice of the nightingale: Tiouou, tiouou, tiouou, tiouou, Shpe tiou tokoua; Tio, tio, tio, tio, Konoutio, konoutiou, konotiou, koutioutio, Tokuo, tskouo, tskouo, tskouo, Tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, tsii, Kouorror, tiou, tksona, pipitksouis, Tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso, tso,tsirrhading. Tsi, tsi, si, tosi, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, Tsorre, tsorre, tsorre, tsorreki; Tsatu, tsatu, tsatu, tsatu, tsatu, tsatu, tsatu, tsi, Dlo, dlo, dlo, dla, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, Kouiou, trrrrrrrrritzt, Lu, ht, lu, ly, ly, ly. Chalons, a celebrated Belgian composer, has set this to music, and Nodier asserts that there is nothing equal to it in the language of imitation. Yet, in the writer's own opinion, it is surpassed in expression, compass of voice, emphasis on the notes, and trill of terminating cadence, by the following rather ungallant imitation, sung by the French peasantry: A ROYAL OPINION ON THE INCOMES OF THE CLERGY The Duke of Cumberland heard a Mr. Mudge, one of our angelic order [a clergyman], and who had a most seraphic finger for the harpsichord, play him a tune at some friendly knight or squire's house, where he was ambushed for him on his way to or from Scotland, and very honestly expresssed great satisfaction at the performance. 'And would your highness think,' says his friend, 'that with such a wonderful talent, this worthy clergyman has not above a hundred a-year? ' 'And do you not think, sir,' replied his highness, 'that when a priest has more, it generally spoils him?''-Rev. Dr Warner, in Jesse's ' George Selwyn and his Contemporaries,' E. 336. |