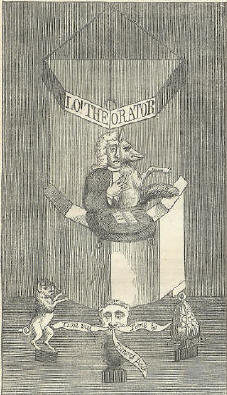

14th OctoberBorn: James II of England, 1633; William Penn, coloniser of Pennsylvania, 1644, London; Charles Abbot, Lord Colchester, lawyer and statesman, 1757, Abingdon. Died: Harold, last Saxon king of England, slain at battle of Hastings, 1066; Pierre Gassendi, mathematician and philosopher, 1655, Paris; Paul Scarron, humorous writer, 1660, Paris; John Henley ('Orator Henley'), 1756, London; James, Marshal Keith, killed at Hochkirchen, 1753; Prince Gregory Alexander Potemkin, favourite of Empress Catherine, 1791, Cherson; Samuel Phillips, novelist and miscellaneous writer, 1854, Brighton. Feast Day: St. Calixtus or Callistus, pope and martyr, 222. St. Donatian, confessor, bishop of Rheims and patron of Bruges, 339. St. Burckard, confessor, first bishop of Wurtzburg, 752. St. Dominic, surnamed Loricatus, confessor, 1060. BATTLE OF HASTINGSThe battle of Hastings, fought on Saturday, the 14th of October 1066, was one of those decisive engagements which at various periods have marked the commencement of a new epoch or chapter in the world's history. Gained by the Duke of Normandy, mainly through superiority of numbers, and several well directed feints, the conduct of the Saxons and their monarch Harold was such as to command the highest admiration on the part of their enemies, and the result might have been very different had Harold, instead of marching impetuously from London with an inadequate army to repel the invaders, waited a little while to gather strength from the reinforcements which were every day pouring in to his standard. But the signal success which, only a few days previous, he had gained over the Norwegians in the north of England, made him overconfident in his own powers, and the very promptitude and rapidity which formed one of his leading characteristics proved the principal cause of his overthrow. On the 28th of September, sixteen days before the battle, the Normans, with their leader William, had disembarked, totally unopposed, from their ships at a place called Bulverhithe, between Pevensey and Hastings. The future Conqueror of England was the last to land, and as he placed his foot on shore, he made a false step, and fell on his face. A murmur of consternation ran through the troops at this incident as a bad omen, but with great presence of mind William sprang immediately up, and shewing his troops his hand filled with English sand, exclaimed: 'What now? What astonishes you? I have taken seism of this land with my hands, and by the splendour of God, as far as it extends it is mine it is yours!' The invading army then marched to Hastings, pitching their camp near the town, and sallying out from this intrenchment to burn and plunder the surrounding country. Landed on a hostile shore, with a brave and vigorous foe to contend with, all William's prospects of success lay in striking a decisive blow before Harold could properly muster his forces or organise his means of resistance. The impetuosity of the Saxon king, as already mentioned, soon furnished him with such an opportunity. Arriving at Senlac, which the bloody engagement a few days subsequently was destined to rechristen by the appellation of Battle, Harold pitched his camp, and then received a message from William, demanding that he should either resign his crown in favour of the Norman, submit the question at issue to the decision of the pope, or finally maintain his right to the English crown by single combat with his challenger. All these proposals were declined by Harold, as was also a last offer made by William to resign to his opponent all the country to the north of the Humber, on condition of the provinces south of that river being ceded to him in sovereignty. On Friday the 13th, the Normans quitted Hastings, and took up their position on an eminence opposite to the English, for the purpose of giving battle on the following day. A singular contrast was noticeable in the manner that the respective armies passed the intervening night. Whilst the Saxons, according to their old convivial custom, spent the time in feasting and rejoicing, singing songs, and quaffing bumpers of ale and wine, the Normans, after finishing their warlike preparations, betook themselves to the offices of devotion, confessed, and received the holy sacrament by thousands at a time.  At early dawn next day, the Normans were marshalled by William and his brother Odo, the warlike bishop of Bayeux, who wore a coat of mail beneath his episcopal robes. They advanced towards the English, who remained firmly intrenched. in their position, and for many hours repulsed steadily with their battle-axes the charge of the enemy's cavalry, and with their closed shields rendered his arrows almost inoperative. Greatability was shewn by William and his brother in rallying their soldiers after these reverses, and the attacks on the English line were again and again renewed. Up to three o'clock in the afternoon, the superiority in the conflict remained with the latter. Then, however, William ordered a thou-sand horse to advance, and then take to flight, as if routed. This stratagem proved fatal to the Saxons, who, leaving their position to pursue the retreating foe, were astounded by the latter suddenly facing about, and falling into disorder, were struck down on every side. The same manoeuvre was twice again repeated with the same calamitous results to the English, and on the last occasion Harold, struck by a random arrow which entered his left eye and penetrated to the brain, was instantaneously killed. This still further increased the disorder of his followers, who, however, bravely maintained the fight round their standard for a time. This at last was grasped by the Normans, who then raised in its stead the consecrated banner, which the pope had sent William from Rome, as a sanction to his expedition. At sunset the combat terminated, and the Normans remained masters of the field. Though by this victory William of Normandy won a kingdom for himself, it was not till years afterwards that he was enabled to sheathe his sword as undisputed sovereign of England. For generations, indeed, the pertinacity so characteristic of the Saxon race displayed itself in a steady though ineffective resistance to their Norman rulers, and for a long time they were animated in their efforts by a legend generally circulated among them, that Harold, their gallant king, instead of being killed, had escaped from the field of battle, and would one day return to lead them to victory. History records many such reports, which, under similar circumstances, have been eagerly adopted by the vanquished party, and are exemplified, among other instances, by the rumours prevalent after the deaths of Don Roderick, the last of the Gothic kings of Spain, and of the Scottish sovereign James IV, who perished at Flodden. FIELD MARSHAL KEITHAmong the eight generals of Frederick the Great, who, on foot, surround Rauch's magnificent equestrian statue of the monarch in Berlin, one is a Briton. He was descended of a Scotch family, once as great in wealth and station as any of the Hamiltons or the Douglases, but which went out in the last century like a quenched light, in consequence of taking a wrong line in politics. James Edward Keith, and his brother the Earl Marischal, when very young men, were engaged in the rebellion of 1715-16, and lost all but their lives. Abroad, they rose by their talents into positions historically more distinguished than those which their youthful imprudence had forfeited. The younger brother, James, first served the czar in his wars against Poland and Turkey; but, becoming discontented with the favouritism that prevailed in the Russian army, and conceiving himself treated with injustice, he gave in his resignation in 1747, and was admitted into the Prussian service as field marshal. Frederick the Great made him his favourite companion, and, together, they travelled incognito through Germany, Poland, and Hungary. Keith also invented a game, in imitation of chess, which delighted the king so much, that he had some thousands of armed men cast in metal, by which he could arrange battles and sieges. On the 29th of August 1756, he entered with the king into Dresden, where he had the archives opened to carry away the documents that particularly interested the Prussian court: he also managed the admirable retreat of the army from Olmutz in the presence of a superior force, without the loss of a single gun; and took part in all the great battles of the period. He was killed in that of Hochkirchen, 14th of October 1758. His correspondence with Frederick, written in French, possesses much historical interest. He was of middle height, dark complexion, strongly marked features, and an expression of determination, softened by a degree of sweetness, marked his face. His presence of mind was very remarkable; and his knowledge, deep and varied in character; whilst his military talents and lively sense of honour made him take rank among the first commanders of the day. His brother, the lord-marshal of Scotland, thus wrote of him to Madame de Geoffrin: 'My brother has left me a noble heritage; after having overrun Bohemia at the head of a large army, I have only found seventy dollars in his purse.' Frederick honoured his memory by erecting a monument to him in the Wilhelmsplatz, at Berlin, by the side of his other generals. ORATOR HENLEYPossessing considerable power of eloquence, with great perseverance, a fair education, and a good position in life, Henley might have pursued a quiet career of prosperity, had not overweening vanity induced him to seek popularity at any risk, and eventually make himself 'preacher and zany of the age,' according to the satirical verdict of Pope, which he had well earned by his ill placed buffoonery. Henley was the son of a clergyman residing at Melton Mowbray, in Leicestershire, where he was born in 1692; he was sent to St. John's College, Cambridge, and while an undergraduate there, sent a communication on punning to the Spectator (printed in No. 396), which is now the most readily accessible of all Ins voluminous writings, scattered as they were in the ephemeral literature of his own day. This paper is a strange mixture of sense and nonsense, combined with a pert self sufficiency, very characteristic of its writer. On his return to Melton, he was employed as assistant in a school. He preached occasionally, and from the attention which his fluency and earnestness attracted, was induced to betake himself to London, as the proper sphere for the display of his rhetorical talents. He was appointed reader at St. George's Chapel, in Queen Square, and afterwards at St. John's, Bedford Row; delivered from time to time charity sermons with great success; and worked at translations for the booksellers. After some years, he was offered a small country living, but would not consent to the obscurity which it entailed. The same exaggeration of style and action in the pulpit, however, which rendered him a favourite with the public, exposed him to animadversion on the part of the clergy and, church patrons. He now attempted political writing, offering his services to the ministry; and when they were declined, made the same offer to their opponents, with no better success. Determined for the future to trust to his own power of eloquence to draw an income from the public, he announced himself as 'the restorer of Ancient Eloquence,' and opened his 'Oratory' in a large room in Butcher Row, Newport Market. Here he preached on Sundays upon theology, and on Wednesdays, on any subject that happened to be most popular. Politics and current events were treated with a vulgar levity that suited the locality. The greatest persons in the land were attacked by him. 'After having undergone some prosecutions, he turned his rhetoric to buffoonery upon all public and private occurrences. All this passed in the same room where at one time he jested, and at another celebrated what he called the 'primitive eucharist'.  In a money point of view, he was very successful, his Oratory was crowded, and cash flowed in freely. For the use of his regular sub-scribers, he issued medals (like the free tickets of theatres and public gardens) with the vain device of a star rising to the meridian, the motto, Ad summa; and, beneath it, Inveniam viam aut faciam. Pope has immortalised 'Henley's gilt tub,' as he terms the gaudy pulpit from which he poured forth his rhapsodies. There is a caricature of him as a clerical fox seated on his tub; a monkey within it acting as clerk, and peeping from the bung hole with a broad grin, as he exhibits a handful of coin, the great end for which he laboured. Henley charged one shilling each for admission to his lectures. Another of these caricatures we here copy. It represents Henley in his pulpit, half clergyman, half fox; his pulpit is supported by a pig, emblematic of the 'swinish multitude;' the 'brazenhead' of the popular romance of Friar Bacon and a well filled purse. The lines of Hudibras are made to apply to him, beginning: Bel and the Dragon's chaplains were More moderate than you by far. In an unlucky hour he attacked Pope, who afterwards held him up to obloquy in the Dunciad: Imbrown'd with native bronze, lo! Henley stands, Tuning his voice, and balancing his hands. How fluent nonsense trickles from his tongue! How sweet the periods, neither said nor sung! Still break the benehes, Henley, with thy strain, While Sherlock, Hare, and Gibson preach in vain. In this old tale, the brazen-head was to do wonders when it spoke but the friar, tired with watching, left his servant to listen while he slept. The head spoke the sentences which appear on the three labels issuing from the mouth, and having spoken the last, fell with a crash that destroyed it. This was typical of the unstable foundation of Henley's popular power. O great restorer of the good old stage, Preacher at once and zany of thy age! 0, worthy thou of Egypt's wise abodes, A decent priest, where monkeys were the gods! But fate with butchers placed thy priestly stall, Meek modern faith to murder, hack, and maul; And bade thee live, to crown Britannia's praise, In Toland's, Tindal's, and in Woolston's days. After some years, Henley left Newport Market, but, faithful to his old friends the butchers, he opened his new Oratory in Clare Market, in the year 1746, and indulged in the most scurrilous censoriousness, and a levity bordering on buffoonery. His neighbours, the butchers, were useful allies, and, it is said, he kept many in pay to protect him from the consequences of his satire. In some instances, the must have run risks of riot and mischief to his meeting room, which could only be repressed by fear of his brawny protectors. In one instance he tricked a mob of shoemakers, by inducing them to come and hear him describe a new mode by which shoes could be made most expeditiously; the plan really being, simply to cut off the tops of ready made boots! His reflections on the royal family led to his arrest, but he was liberated, after a few days, on proper bail being tendered, and a promise to curb his tongue in future. His ordinary free and easy vulgarity is well hit off in an article on the 'Robin Hood Society,' published in No. 18 of the Gray's Inn Journal, February 17, 1753; he is called Orator Bronze, and exclaims: I am pleased to see this assembly; you 're a twig from me, a chip of the old block at Clare Market; I am the old block, invincible; coup de grace, as yet unanswered. We are brother rationalists; logicians upon fundamentals! I love ye all I love mankind in general give me some of that porter! Despite his boldness and impudence, and the daring character of his disquisitions on politics and religion, Henley found a difficulty in keeping up an interest in his Oratory. A contemporary writer says: 'for some years before its author's death, it dwindled away so much that the few friends of it feared its decease was very near. The doctor, indeed, kept it up to the last, determined it should live as long as he did, and actually exhibited many evenings to empty benches. Finding no one at length would attend, he admitted the acquaintances of his door keeper, runners, &c., gratis. On the 13th of October 1753, the doctor died, and the Oratory ceased, no one having iniquity or impudence sufficient to continue it.' Irrespective of the improper character of the subjects he chose to descant upon, his inordinate conceit induced him to treat every one as his inferior in judgment; and he enforced his opinions with the most violent gesticulation. Henley's feverish career is a glaring instance of vanity overcoming and degrading abilities, that, properly cultivated, might have insured him a respectable position, instead of an anxious and fretful life, and an immortality in the pages of a great satirist, of a most undesirable nature. |