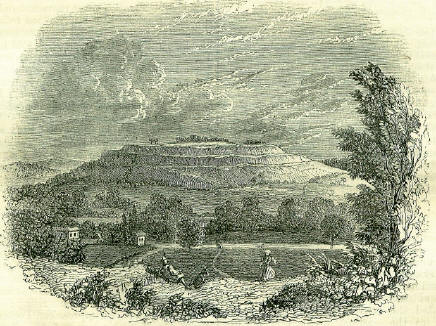

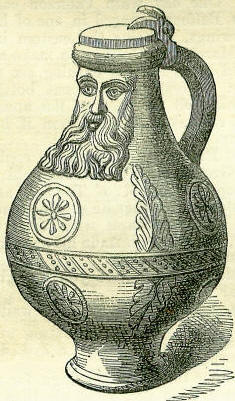

14th MarchDied: John, Earl of Bedford, 1555; Simon Morin, burned, 1663; Marshal-General Wade, 1751; Admiral John Byng, shot at Portsmouth, 1757; William Melmoth, accomplished scholar, 1799, Bath; Baines Barrington, antiquary, lawyer, and naturalist, 1800, Temple; Frederick Theophilus Klopstock, German poet, 1803, Ottensen; George Papworth, architect and engineer, 1855. Feast Day: St. Acepsimas, bishop in Assyria, Joseph, and Aithilahas, martyrs, 380. St. Boniface, bishop of Ross, in Scotland, 630. St. Maud, Queen of Germany, 968. JOHN RUSSELL, FIRST EARL OF BEDFORDThe importance of the noble house of Bedford during the last three centuries may be traced to the admirable personal qualities of a mere private gentleman-'a Mr. Russell '-in connection with a happy fortuitous occurrence. The gentleman here referred to was the eldest, or only son of James Russell of Berwick, a manor-place in the county of Dorset, about a mile from the seacoast. He was, however, born at Kingston-Russell in the same county, where the elder branch of the family had resided from the time of the Conquest. At an early age he was sent abroad to travel, and to acquire a knowledge of the continental languages. He returned in 1506 an accomplished gentleman, and a good linguist, and took up his residence with his father at Berwick. Shortly after his arrival a violent tempest arose, and on the next morning, 11th January, 1506, three foreign vessels appeared on the Dorset coast making their way for the port of Weymouth. Information being given to the Governor, Sir Thomas Trenchard, he repaired to the coast with a body of men prepared to meet the vessels whether belonging to friends or foes. On reaching the harbour they were found to be part of a convoy under the command of Philip, Archduke of Austria, and only son of Maximilian I, Emperor of Germany. This young prince had just married Johanna, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, King and Queen of Castile and Arragon, and was on his way to Spain when overtaken by the storm which had, separated the vessel in which he was sailing and two others from the rest of the convoy, and had forced them to take shelter in Weymouth Harbour. Sir Thomas Trenchard immediately conducted the Archduke to his own castle, and sent messengers to apprize the King, Henry the Seventh, of his arrival. While waiting for the King's reply, Sir Thomas invited his cousin and neighbour, young Mr. Russell of Berwick, to act as interpreter and converse with the Archduke on topics connected with his own country, through which Mr. Russell had lately travelled. ''It is an ill wind,' says Fuller, referring to this incident, 'that blows nobody profit:' so this accident (of the storm) proved the foundation of Mr. Russell's preferment.' For the Archduke was so delighted with his varied knowledge and courteous bearing, that, on deciding to proceed at once to Windsor, he requested Mr. Russell to accompany him, and when they arrived there, he recommended him so highly to the King's notice, that he granted him an immediate interview. Henry was extremely struck with. Mr. Russell's conversation and appearance: 'for,' says Lloyd, 'he had a moving beauty that waited on his whole body, a comportment unaffected, and such a comeliness in his mien, as exacted a liking, if not a love, from all that saw him; the whole set off with a person of a middle stature, neither tall to a formidableness, nor short to a contempt, straight and proportioned, vigorous and active, with pure blood and spirits flowing in his youthful veins.' Mr. Russell was forthwith appointed a gentleman of the Privy Chamber. Three years afterwards, Henry VIII ascended the throne, and was not slow to perceive Mr. Russell's great and varied talents. He employed him in important posts of trust and difficulty, and found him an able and faithful diplomatist on every occasion. Consequently he rewarded him with immense grants of lands,-chiefly from the dissolved monasteries,-and loaded him with honours. He was knighted; was installed into the Order of the Garter, and was raised to the peerage as Baron Russell of Chenies. He was made Marshal of Marshalsea; Controller of the King's Household; a Privy Councillor; Lord Warden of the Stannaries in the counties of Devon and Cornwall; President of these counties and of those of Dorset and Somerset; Lord Privy-Seal; Lord Admiral of England and Ireland; and Captain-General of the Vanguard in the Army. Lastly, the King, on his death-bed, appointed Lord Russell, who was then his Lord Privy-Seal, to be one of the counsellors to his son, Prince Edward. On Edward VI ascending the throne, Lord Russell still retained his position and influence at Court. On the day of the coronation he was Lord High Steward of England for the occasion, and soon afterwards employed by the young Protestant king to promote the objects of the Reformation, which he did so effectually that, as a reward, he was created Earl of Bedford, and endowed with the rich abbey of Woburn, which soon afterwards became, as it still continues to be, the principal seat of the family. On the accession of the Catholic Mary, though Lord Russell had so zealously promoted the Reformation, and shared so largely in the property of the suppressed monasteries, yet he was almost immediately received into the royal favour, and reappointed Lord Privy-Seal. Within the same year he was one of the noble-men commissioned to escort Philip from Spain to become the Queen's husband, and to give away her Majesty at the celebration of her marriage. This was his last public act. And it is remarkable that as Philip, the Archduke of Austria, first introduced him to Court, so that Duke's grandson, Philip of Spain, was the cause of his last attendance there. It was more remarkable that he was able to pursue a steady upward course through those great national convulsions which shook alike the altar and the throne; and to give satisfaction to four successive sovereigns, each differing widely from the other in age, in disposition, and in policy. From the wary Henry VII, and his capricious and arbitrary son; from the Protestant Edward and the Romanist Mary, he equally received unmistakeable evidences of favour and approbation. But the most remarkable, and the most gratifying fact of all is, that he appears to have preserved an integrity of character through the whole of his extraordinary and perilous career. There is nothing in his correspondence, or in any early notice of him that betrays the character of a time-serving courtier. The true cause of his continuing in favour doubtless lay in his natural urbanity, his fidelity, and, perhaps, especially in that skill and experience in diplomacy which made his services so valuable, if not essential, to the reigning sovereign. He died, 'full of years as of honours,' on the 14th of March, 1555, and was buried at Chenies, in Bucks, the manor of which he had acquired by his marriage. The countess, who survived him only three years, built for his remains a large vault and sepulchral chapel adjoining the parish church; and a magnificent altar tomb, bearing their effigies in life-size, was erected to commemorate them by their eldest son, Francis, second Earl of Bedford. The chapel, which has ever since been the family burial-place, now contains a fine series of monuments, all of a costly description, ranging from the date of the Earl's death to the present century; and the vault below contains between fifty and sixty members of the Russell family or their alliances. The last deposited in it was the seventh Duke of Bedford, who died 14th May, 1861. The Earl of Bedford, when simply Sir John Russell, was frequently sent abroad both on friendly and hostile expeditions, and lied many narrow escapes of life. On one occasion, after riding by night and day through rough and circuitous roads to avoid detachments of the enemy, he came to a small town, and rested at an obscure inn, where he thought he might with safety refresh himself and his horse. But before he could begin the repast which had been prepared for him, he was informed that a body of the enemy, who were in pursuit of him, were approaching the town. He sprang on his horse, and without tasting food, rode off at full speed, and only just succeeded in leaving the town at one end while his pursuers entered it at the other. On another occasion the hotel in which he was staying was suddenly surrounded by a body of men who were commissioned to take him alive and send him a captive to Franco. From this danger he was rescued by Thomas Cromwell, who passed himself off to the authorities as a Neapolitan acquaintance of Russell's, and promised that if they would give him access to him, he would induce him to yield himself up to them without resistance. This adventure was introduced into a tragedy entitled The Life and Death, of Thomas, Lord Cromwell, which is supposed to have been written by Heywood, in the reign of Elizabeth; and from which the following is a brief extract: MARSHAL WADEField-Marshal George Wade died at the age of eighty, possessed of above £100,000. In the course of a military life of fifty-eight years, his most remarkable, though not his highest service was the command of the forces in Scotland in 1724, and subsequent years, during which he superintended the construction of those roads which led to the gradual civilization of the Highlands. Had you seen those roads before they were made, You'd have lifted up your hands and blessed General Wade, sung an Irish ensign in quarters at Fort William, referring in reality to the tracks which had previously existed on the same lines, and which are roads in all respects but that of being made, i. e. regularly constructed; and, doubtless, it was a work for which the general deserved infinite benedictions. Wade had also much to do in counteracting and doing away with the Jacobite predilections of the Highland clans; in which kind of business it is admitted that he acted a humane and liberal part. He did not so much force, as reason the people out of their prejudices. The general commenced his Highland roads in 1726, employing five hundred soldiers in the work, at sixpence a-day of extra pay, and it was well advanced in the three ensuing years. He himself employed, in his surveys, an English coach, which was everywhere, even at Inverness, the first vehicle of the kind ever seen; and great was the wonder which it excited among the people, who invariably took off their bonnets to the driver, as supposing him the greatest personage connected with it. When the men had any extra hard work, the general slaughtered an ox and gave them a feast, with something liquid wherewith to drink the king's health. On completing the great line by Drumuachter, in September 1729, he held high festival with his highwaymen, as he called them, at a spot near Dalnaspidal, opposite the opening of Loch Garry, along with a number of officers and gentlemen, six oxen and four ankers of brandy being consumed on the occasion. Walpole relates that General Wade was at a low gaming house, and had a very fine snuff -box, which on a sudden he missed. Everybody denied having taken it, and he insisted on searching the company. He did; there remained only one man who stood behind him, and refused to be searched unless the general would go into another room alone with him. There the man told him that he was born a gentleman, was reduced, and lived by what little bets he could pick up there, and by fragments which the waiters sometimes gave him. 'At this moment I have half a fowl in my pocket. I was afraid of being exposed. Here it is! Now, sir, you may search me.' Wade was so affected, that he gave the man a hundred pounds; and 'immediately the genius of generosity, whose province is almost a sinecure, was very glad of the opportunity of making him find his own snuff' box, or another very like it, in his own pocket again.' DEATH OF ADMIRAL BYNGThe execution of Admiral Byng for not doing the utmost with his fleet for the relief of Port Mahon, in May 1756, was one of the events of the last century which made the greatest impression on the popular mind. The account of his death in Voltaire's Candide, is an exquisite bit of French epigrammatic writing: Talking thus, we approached Portsmouth. A multitude of people covered the shore, looking attentively at a stout gentleman who was on his knees with his eyes bandaged, on the quarter-deck of one of the vessels of the fleet. Four soldiers, placed in front of him, put each three balls in his head, in the most peaceable manner, and all the assembly then dispersed quite satisfied. What is all this?' quoth Candide, 'and what devil reigns here?' He asked who was the stout gentleman who came to die in this ceremonious manner. 'It is an Admiral,' they answered. 'And why kill the Admiral?' 'It is because he has not killed enough of other people. He had to give battle to a French Admiral, and they find that he did not go near enough to him.' 'But,' said Candide, 'the French Admiral was as far from him as he was from the French Admiral.' 'That is very true,' replied they; 'but in this country it is useful to kill an Admiral now and then, just to encourage the rest [pour encourager les autres].' THE REFORM ACT OF 1831-2: OLD SARUMThe 14th of March 1831 is a remarkable day in English history, as that on which the celebrated bill for parliamentary reform was read for the first time in the House of Commons. The changes proposed in this bill were sweeping beyond the expectations of the most sanguine, and caused many advocates of reform to hesitate. So eagerly, however, did the great body of the people lay hold of the plan-demanding, according to a phrase of Mr. Rintoul of the Spectator newspaper, the 'Bill, the whole Bill, and nothing but the Bill,'-that it was found impossible for all the conservative influences of the country, including latterly that of royalty itself, to stay, or greatly alter the measure. It took fourteen months of incessant struggle to get the bill passed; but no sooner was the contest at an end than a conservative reaction set in, falsifying alike many of the hopes and fears with which the measure had been regarded. The nation calmly resumed its ordinary aplomb, and moderate thinkers saw only occasion for congratulation that so many perilous anomalies had been re-moved from our system of representation. Amongst these anomalies there was none which, the conservative party felt it more difficult to defend, than the fact that at least two of the boroughs possessing the right of returning two members, were devoid of inhabitants, namely Gatton and Old Sarum. 'Gatton and Old Sarum' were of course a sort of tour de force in the hands of the reforming party, and the very names became indelibly fixed in the minds of that generation. With many Old Sarum thus acquired a ridiculous association of ideas, who little knew that, in reality, the attributes of the place were calculated to raise sentiments of a beautiful and affecting kind.  Old Sarum, situated a mile and a half north of Salisbury-now a mere assemblage of green mounds and trenches-is generally regarded as the Sorbiodunum of the Romans. Its name, derived from the Celtic words, sorbio, dry, and dun, a fortress, leads to the conclusion that it was a British post: it was, perhaps, one of the towns taken by Vespasian, when he was engaged in the subjugation of this part of the island under the Emperor Claudius. A number of Roman roads meet at Old Sarum, and it is mentioned the Antonine Itinerary, thus shewing the place to have been occupied by the Romans, though, it must be admitted, the remains present little resemblance to the usual form of their posts. In the Saxon times, Sarum is frequently noticed by historians; and under the Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman princes, councils, ecclesiastical and civil, were held here, and the town became the seat of a bishopric. There was a castle or fortress, which is mentioned as early as the time of Alfred, and which may be regarded as the citadel. The city was defended by a wall, within the enclosure of which the cathedral stood. Early in the thirteenth century, the cathedral was removed to its present site; many or most of the citizens also removed, and the rise of New Sarum, or Salisbury, led to the decay of the older place; so that, in the time of Leland (sixteenth century), there was not one inhabited house in it. The earthworks of the ancient city are very conspicuous, and traces of the foundation of the cathedral were observed about thirty years ago. Mr. Constable, R.A., was so struck with the desolation of the site, and its lonely grandeur, that he painted a beautiful picture of the scene, which was ably engraved by Lucas. The plate was accompanied with letter-press, of which the following are passages: 'This subject, which seems to embody the words of the poet, 'Paint me a desolation,' is one with which the grander phenomena of nature best accord. Sudden and abrupt appearances of light-thunder-clouds-wild autumnal evenings-solemn and shadowy twilights, ' flinging half an image on the straining sight '-with variously tinted clouds, dark, cold, and grey, or ruddy bright-even conflicts of the elements heighten, if possible, the sentiment which belongs to it. 'The present appearance of Old Sarum, wild, desolate, and dreary, contrasts strongly with its former splendour. This celebrated city, which once gave laws to the whole kingdom, and where the earliest parliaments on record were convened, can only now be traced by vast embankments and ditches, tracked only by sheep-walks.' The plough has passed over it.' In this city, the wily Conqueror, in 1086, confirmed that great political event, the establishment of the feudal system, and enjoined the allegiance of the nobles. Several succeeding monarchs held their courts here; and it too often screened them after their depredations on the people. In the days of chivalry, it poured forth its Longspear and other valiant knights over Palestine. It was the seat of the ecclesiastical government, when the pious Osmond and the succeeding bishops diffused the blessings of religion over the western kingdom: thus it became the chief resort of ecclesiastics and warriors, till their feuds and mutual animosities, caused by the insults of the soldiery, at length occasioned the separation of the clergy, and the removal of the Cathedral from within its walls, which took place in 1227. Many of the most pious and peaceable of the inhabitants followed it, and in less than half a century after the completion of the new church, the building of the bridge over the river Harnham diverted the great western road, and turned it through the new city. This last step was the cause of the desertion and gradual decay of Old Sarum.' SMITHFIELD MARTYRS' ASHESFanaticism sent many Protestants to the stake at Smithfield in the time of Queen Mary. The place of their suffering is supposed to have been on the south-east side of the open area, for old engravings still extant represent some of the buildings known to have existed on that side, as backing the scene of the burnings. Ashesand bones have more than once been found, during excavations in that spot; and it has long been surmised that those were part of the remains of the poor martyrs. A discovery of this kind occurred on the 14th March 1849. Excavations were in progress on that day, connected with the construction of a new sewer, near St. Bartholomew's church. At a depth of about three feet beneath the surface, the workmen came upon a heap of unhewn stones, blackened as if by fire, and covered with ashes and human bones, charred and partially consumed. One of the city antiquaries collected some of the bones, and carried them away as a memorial of a time which has happily passed. If there had only been a few bones present, their position might possibly be explained in some other way; and so might a heap of fire-blackened stones; but the juxtaposition of the two certainly gives the received hypothesis a fair share of probability. THE GREYBEARD, OR BELLARMHNEThe manufacture of a coarse strong pottery, known as 'stoneware,' from its power of with-standing fracture and endurance of heat, originated in the Low Countries in the early part of the sixteenth century. The people of Holland particularly excelled in the trade, and the productions of the town of Delft were known all over Christendom.  During the religious feuds which raged so horribly in Holland, the Protestant party originated a design for a drinking jug, in ridicule of their great opponent, the famed Cardinal Bellarmine, who had been sent into the Low Countries to oppose in person, and by his pen, the progress of the Reformed religion. He is described as 'short and hard-featured,' and thus he was typified in the corpulent beer-jug here delineated. To make the resemblance greater, the Cardinal's face, with the great square-cut beard then peculiar to ecclesiastics, and termed 'the cathedral beard,' was placed in front of the jug, which was as often called 'a grey-beard' as it was 'a Bellarmine.' It was so popular as to be manufactured by thousands, in all sizes and qualities of cheapness; sometimes the face was delineated in the rudest and fiercest style. It met with a large sale in England, and many fragments of these jugs of the reign of Elizabeth and James I have been exhumed in London. The writers of that era very frequently allude to it. Bulwer, in his Artificial Changeling, 1653, says of a formal doctor, that 'the fashion of his beard was just, for all the world, like those upon Flemish jugs, bearing in gross the form of a broom, narrow above and broad beneath.' Ben Jonson, in Bartholomew Fair, says of a drunkard, 'The man with the beard has almost struck up his heels.' But the best description is the following in Cartwright's play, The Ordinary, 1651.: - Thou thing! Thy belly looks like to some strutting hill, O'ershaclowed with thy rough beard like a wood; Or like a larger jug, that some men call A Bellarmine, bat we a conscience, Whereon the tender hand of pagan workman Over the proud ambitious head hath carved An idol large, with beard episcopal, Making the vessel look like tyrant Eglon! The term Greybeard is still applied in Scotland to this kind of stoneware jug, though the face of Bellarmine no longer adorns it. A story connected with Greybeards was taken down a few years ago from the conversation of a venerable prelate of the Scottish Episcopal church; and though it has appeared before in a popular publication, we yield to the temptation of bringing it before the readers of the BOOK OF DAYS: About 1770, there flourished a Mrs. Balfour of Denbog, in the county of Fife. The nearest neighbour of Denbog was a Mr. David Paterson, who had the character of being a good deal of a humorist. One day when Paterson called, he found Mrs. Balfour engaged in one of her half-yearly brewings, it being the custom in those days each March and October to make as much ale as would serve for the ensuing six months. She was in a great pother about bottles, her stock of which fell far short of the number required, and she asked Mr. Paterson if he could lend her any. 'No,' said Paterson, 'but I think I could bring you a few Greybeards that would hold a good deal; perhaps that would do.' The lady assented, and appointed a day when he should come again, and bring his Greybeards with him. On the proper day, Mr. Paterson made his appearance in Mrs. Balfour's little parlour. Well, Mr. Paterson, have you brought your Greybeards?' 'Oh yes. They're down stairs waiting for you., 'How many?' Nae less than ten.' 'Well, I hope they're pretty large, for really I find I have a good deal more ale than I have bottles for.' 'I'se warrant ye, mom, ilk ane o' them will hold twa gallons.' Oh, that will do extremely well.' Down goes the lady. 'I left them in the dining-room,' said Paterson. When the lady went in, she found ten of the most bibulous old lairds of the north of Fife. She at once perceived the joke, and entered into it. After a hearty laugh. had gone round, she said she thought it would be as well to have dinner before filling the greybeards; and it was accordingly arranged that the gentlemen should take a ramble, and come in to dinner at two o'clock. The extra ale is understood to have been duly disposed of. |