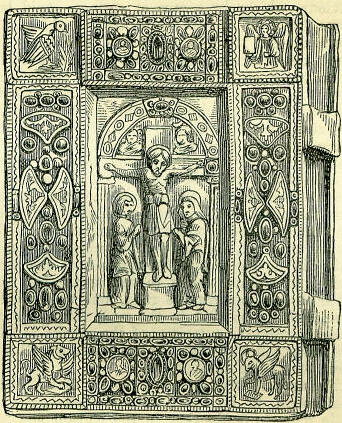

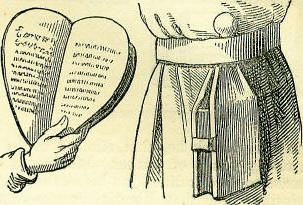

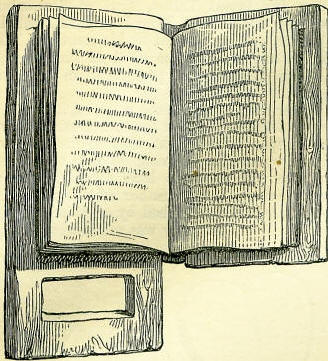

13th SeptemberBorn: Sir William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, 1520, Bourn, Leicestershire. Died: Titus, Roman emperor, 81 A.D.; Sir John Choke, eminent Greek scholar, 1557, London; William Farel, coadjutor of Calvin, 1565, Neufchatel; Michael de Montaigne, celebrated essayist, 1592, Montaigne, near Bordeaux; Philip II of Spain, 1598; John Buxtorf the Elder, eminent Hebrew scholar, 1629, Basel; General James Wolfe, killed at capture of Quebec, 1759; Charles James Fox, eminent statesman, 1806, Chiswick House; Saverio Bettinelli, Italian writer (Risorgimento d'Italia), 1808, Mantua. Feast Day: St. Maurilius, bishop of Angers, confessor, 5th century. St. Eulogius, confessor and patriarch of Alexandria, 608. St. Amatus, abbot and confessor, about 627. Another St. Amatus, bishop and confessor, about 690. MONTAIGNEMontaigne was born in 1533, and died in 1592, his life of sixty years coinciding with one of the gloomiest eras in French history--a time of wide-spread and implacable dissensions, of civil war, massacre and murder. Yet, as the name of Izaak Walton suggests little or nothing of the strife between Cavalier and Roundhead, so neither does that of Montaigne recall the merciless antagonism of Catholic and Huguenot. Walton and Montaigne alike sought refuge from public broils in rural quiet, and in their solitude produced writings which have been a joy to the contemplative of many generations; but here the likeness between the London linen-draper and the Gascon lawyer ends: they were men of very different characters. The father of Montaigne was a baron of Perigord. Having found Latin a dreary and difficult study in his youth, he determined to make it an easy one for his son. He procured a tutor from Germany, ignorant of French, and gave orders that he should converse with the boy in nothing but Latin, and directed, moreover, that none of the household should address him otherwise than in that tongue. 'They all became Latinised,' says Montaigne; 'and even the villagers in the neighbourhood learned words in that language, some of which took root in the country, and became of common use among the people.' Greek he was taught by similar artifice, feeling it a pastime rather than a task. At the age of six, he was sent to the college of Avenue, then reputed the best in France, and, strange as it seems, his biographers relate, that at thirteen he had run through the prescribed course of studies, and completed his education. He next turned his attention to law, and at twenty-one was made conseiller, or judge, in the parliament of Bordeaux. He visited Paris, of which he wrote: I love it for itself; I love it tenderly, even to its warts and blemishes. I am not a Frenchman, but by this great city-great in people, great in the felicity of her situation, but above all, great and incomparable in variety and diversity of commodities; the glory of France, and one of the most noble ornaments of the world. He was received at court, enjoyed the favour of Henri II, saw Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, and entered fully into the delights and dissipations of gay society. At thirty-three he was married though had he been left free to his choice, he 'would not have wedded with Wisdom herself had she been willing. But 'tis not much to the purpose,' he writes, 'to resist custom, for the common usance of life will be so. Most of my actions are guided by example, not choice.' Of women, indeed, he seldom speaks save in terms of easy contempt, and for the hardships of married life he has frequent jeers. In 1571, in his thirty-eighth year, the death of his father enabled Montaigne to retire from the practice of law, and to settle on the patrimonial estate. It was predicted he would soon exhaust his fortune, but, on the contrary, he proved a good economist, and turned his farms to excellent account. His good sense, his probity, and liberal soul, won for him the esteem of his province; and though the civil wars of the League converted every house into a fort, he kept his gates open, and the neighbouring gentry brought him their jewels and papers to hold in safe-keeping. He placed his library in a tower overlooking the entrance to his court-yard, and there spent his leisure in reading, meditation, and writing. On the central rafter he inscribed: I do not understand; I pause; I examine. He took to writing for want of something to do, and having nothing else to write about, he began to write about himself, jotting down what came into his head when not too lazy. He found paper a patient listener, and excused his egotism by the consideration, that if his grandchildren were of the same mind as himself, they would he glad to know what sort of man he was. 'What should I give to listen to some one who could tell me the ways, the look, the bearing, the commonest words of my ancestors!' If the world should complain that he talked too much about himself, he would answer the world that it talked and thought of everything but itself. A volume of these egotistic gossips he published at Bordeaux in 1580, and the book quickly passed into circulation. About this time he was attacked with stone, a disease he had held in dread from childhood, and. the pleasure of the remainder of his life was broken with paroxysms of severe pain. When they suppose me to he most cast down,' he writes, and spare me, I often try my strength, and start subjects of conversation quite foreign to my state. I can do everything by a sudden effort, but, oh! take away duration. I am tried severely, for I have suddenly passed from a very sweet and happy condition of life, to the most painful that can be imagined.' Abhorring doctors and drugs, he sought diversion and relief in a journey through Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. At Rome he was kindly received by the pope and cardinals, and invested with the freedom of the city, an honour of which he was very proud. He kept a journal of this tour, which, after lying concealed in an old chest in his chateau for nearly two hundred years, was brought to light and published in 1774; and, as may be supposed, it contains a stock of curious and original information. While he was travelling, he was elected mayor of Bordeaux, an office for which he had no inclination, but Henry III insisted that he should accept it, and at the end of two years he was re-elected for the same period. During a visit to Paris, he became acquainted with Mademoiselle de Gournay, a young lady who had.conceived an ardent friendship for him through reading his Essays. She visited him, accompanied by her another, and he reciprocated her attachment by treating her as his daughter. Meanwhile, his health grew worse, and feeling his end was drawing near, and sick of the intolerance and bloodshed which devastated France, he kept at home, correcting and retouching his writings. A quinsy terminated his life. He gathered his friends round his bedside, and bade them farewell. A priest said mass, and at the elevation of the host he raised himself in bed, and with hands clasped in prayer, expired. Mademoiselle de Gournay and her mother crossed half France, risking the perils of the roads, that they might condole with his widow and daughter. It is superfluous to praise Montaigne's Essays; they have long passed the ordeal of time into assured immortality. He was one of the earliest discoverers of the power and genius of the French language, and may he said to have been the inventor of that charming form of literature-the essay. At a time when authorship was stiff, solemn, and exhaustive, confined to Latin and the learned, he broke into the vernacular, and wrote for everybody with the ease and nonchalance of conversation. The Essays furnish a rambling auto-biography of their author, and not even Rousseau turned himself inside out with more completeness. He gives, with inimitable candour, an account of his likes and dislikes, his habits, foibles, and virtues. He pretends to most of the vices; and if there be any goodness in him, he says he got it by stealth. In his opinion, there is no man who has not deserved hanging five or six times, and he claims no exception in his own behalf. 'Five or six as ridiculous stories,' he says, 'may he told of me as of any man living.' This very frankness has caused. some to question his sincerity, but his dissection of his own inconsistent self is too consistent with flesh and blood to be anything but natural. Bit by bit the reader of the Essays grows familiar with Montaigne; and he must have a dull imagination indeed who fails to conceive a distinct picture of the thick-set, square-built, clumsy little man, so undersized that he did not like walking, because the mud of the streets bespattered him to the middle, and the rude crowd jostled and elbowed him. He disliked Protestantism, but his mind was wholly averse to bigotry and persecution. Gibbon, indeed, reckons Montaigne and Henri IV as the only two men of liberality in the France of the sixteenth century. Nothing more distinguishes Montaigne than his deep sense of the uncertainty and provisional character of human knowledge; and Mr. Emerson has well chosen him for a type of the sceptic. Montaigne's device-a pair of scales evenly balanced, with the motto, Quo scais je? (What do I know?)-perfectly symbolises the man. The only book we have which we certainly know was handled by Shakspeare, is a copy of Florio's translation of Montaigne's Essays. It contains the poet's autograph, and was purchased. by the British Museum for one hundred and twenty guineas. A second copy of the same translation in the Museum has Ben Jonson's name on the fly-leaf. ANCIENT BOOKSBefore the invention of printing, the labour requisite for the production of a manuscript volume was so great, that such volume, when completed, became a treasured heir-loom. Half-a-dozen such books made a remarkable library for a nobleman to possess; and a score of them would furnish a monastery. Many years must have been occupied in writing the large folio volumes that are still the most valued books in the great public libraries of Europe; vast as is the labour of the literary portion, the artistic decoration of these elaborate pages of elegantly-formed letters, is equally wonderful. Richly-painted and gilt letters are at the head of chapters and paragraphs, from which vignette decoration flows down the sides, and about the margins, often enclosing grotesque figures of men and animals, exhibiting the fertile fancies of these old artists. Miniature drawings, frequently of the greatest beauty, illustrating the subject of each page, are sometimes spread with a lavish hand through these old volumes, and often furnish us with the only contemporary pictures we possess of the everyday-life of the men of the middle ages. When the vellum leaves completing the book had been written and decorated, the binder then commenced his work; and he occasionally displayed a costly taste and manipulative ability of a kind no moderns attempt. A valued volume was literally encased in gold and gems. The monks of the ninth and tenth centuries were clever adepts in working the precious metals; and one of the number-St. Dunstan-became sufficiently celebrated for his ability this way, to be chosen the patron-saint of the goldsmiths.  Our engraving will convey some idea of one of the finest existing specimens of antique bookbinding in the national collection, Paris. It is a work of the eleventh century, and encases a book of prayers in a mass of gold, jewels, and enamels. The central subject is sunk like a framed picture, and represents the Crucifixion, the Virgin and St. John on each side the cross, and above it the veiled busts of Apollo and Diana; thus exhibiting the influence of the older Byzantine school, which is, indeed, visible throughout the entire design. This subject is executed on a thin sheet of gold, beaten up from behind into high relief, and chased upon its surface. A rich frame of jewelled ornament surrounds this subject, portions of the decoration being further enriched with coloured enamels; the angles are filled with enamelled emblems of the evangelists; the ground of the whole design enriched by threads and foliations of delicate gold wire. Such books were jealously guarded. They represented a considerable sum of money in a merely mercantile sense; but they often had additional value impressed by some individual skill. Loans of such volumes, even to royalty, were rare, and never accorded without the strictest regard to their safety and sure return. Gifts of such books were the noblest presents a monastery could offer to a prince; and such gifts were often made the subject of the first picture on the opening page of the volume. Thus the volume of romances, known as The Shrewsbury Book, in the British Museum, has upon its first page an elaborate drawing, representing the famed Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, presenting this book to King Henry VI, seated on his throne, and surrounded by his courtiers. Many instances might readily be cited of similar scenes in other manuscripts preserved in the same collection. Smaller and less ambitious volumes, intended for the use of the student, or for church-services, were more simply bound; but they frequently were enriched by an ivory carving let into the cover-a practice that seems to have ceased in the sixteenth century, when leather of different kinds was used, generally enriched by ornament stamped in relief.  A quaint fancy was sometimes indulged in the form of books, such as is seen in the first figure of the cut just given. The original occurs in a portrait of a nobleman of that era, engaged in devotion, his book of prayers taking the conventional form of a heart, when the volume is opened. For the use of the religious, books of prayers were bound, in the fifteenth century, in a very peculiar way, which will be best understood by a glance at the second figure in our cut. The leathern covering of the volume was lengthened beyond the margin of the boards, and then gathered (a loose flap of skin) into a large knot at the end. When the book was closed and secured by the clasp, this leathern flap was passed under the owner's girdle, and the knot brought over it, to prevent its slipping. Thus a volume of prayers might be conveniently carried, and such books were very constantly seen at a monk's girdle. There is another class of books for which great durability, during rough usage, was desired. These were volumes of accounts, registers, and law records. Strong boards sometimes formed their only covering, or the boards were covered with hog-skins, and strengthened by bosses of metal.  The town of Southampton still possesses a volume containing a complete code of naval legislation, written in Norman-French, on vellum, in a hand apparently of the earlier half of the fourteenth century. It is preserved in its original binding, consisting of two oak boards, about half an inch thick, one of them being much longer than the other, the latter having a square hole in the lower part, to put the hand through, in order to hold it up while citing the laws in court. These boards are held together by the strong cords upon which the back of the book is stitched, and which pass through holes in the wooden covers. These are again secured by bands of leather and rows of nails. Paper-books, intended for ordinary use, were sometimes simply covered with thick hog skin, stitched at the back with strong thongs of leather. Binding, as a fine art, seems to have declined just before the invention of printing: after that, libraries became common, and collectors prided themselves on good book-binding; but into this more modern history of the art we do not propose to enter. |